Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies

Introduction

By Hammerson Peters

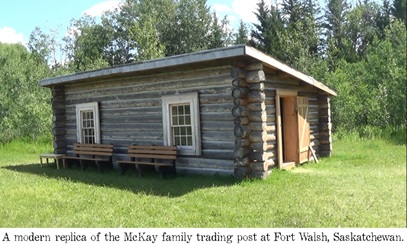

Imagine that it is the spring of 1876. You’re lounging on a bench on the deck of your family’s log cabin, which doubles as your family’s trading post, enjoying an evening smoke with your swarthy mustachioed brother-in-law. It is sundown in the Cypress Hills, and the lodgepole pines which crown the surrounding slopes are fading into dusky silhouettes against a crimson sky.

As you draw on your pipe, you and your companion spot a lone rider in the distance- an Indian approaching the palisaded walls of nearby Fort Walsh. The rider is hailed by the guards and ushered inside the fort. Just as you begin to replenish your dwindling bowl, he emerges again, this time accompanied by an officer of the North-West Mounted Police. Taking the lead, the policeman spurs his horse to a brisk trot and heads straight towards you.

The Indian, you soon learn, is the advance scout of an Assiniboine band which is in the process of making camp on Battle Creek about three miles to the southeast, at the edge of the prairie. Buffalo are harder to come by these days, and with their winter pemmican stores all but exhausted, the Assiniboine are in desperate need of food.

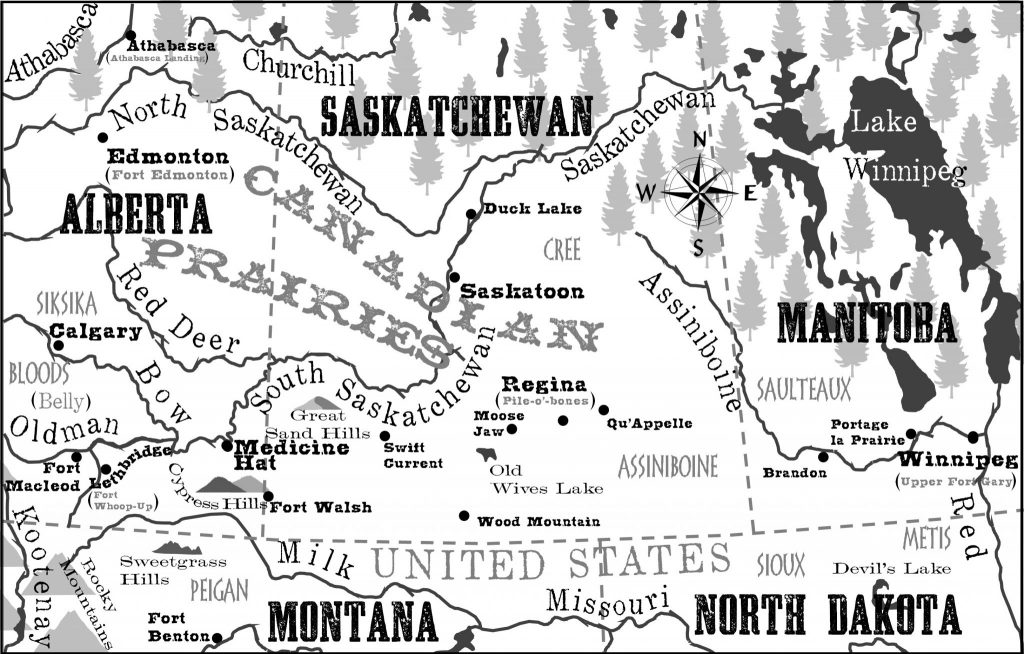

The band intends to camp outside the fort tomorrow, but refuses to complete the journey until morning. If they proceed up the trail any further, they will come to the spot at which several dozen of their kin were killed three years prior in the event which has come to be known as the Cypress Hills Massacre. Anyone who travels through that haunted valley at night, the Assiniboine believe, runs the risk of encountering those spirits of the dead who have yet to make the journey to the Great Sand Hills- the final resting place of all Plains Indian souls north of the Medicine Line.

The red-coated Mountie informs you that, although the band will be properly treated in the morning, he has been tasked with bringing some bacon and a few sacks of flour to them tonight as a gesture of goodwill. His own knowledge of the Assiniboine language is rudimentary at best, but doubtless most of the Indians speak the Plains Cree tongue- a language in which you are perfectly fluent. Would you consent to accompany him to the Assiniboine camp and lend him your interpretive services tonight?

You agree. You grab your rifle and your woolen Hudson’s Bay Company blanket and hitch your horse up to your two-wheeled Red River cart, the latter being less cumbersome than the heavy NWMP wagon which the Mountie might have otherwise employed. After taking on some provisions at the fort, you and your two new companions head down Battle Creek. The Red River cart is a two-wheeled all-wooden wagon invented by the Metis people of what is now Manitoba, and was originally used to transport goods associated with the 19th Century fur trade.

The journey takes about half an hour, bringing you past the charred remains of the American whisky forts outside which the aforementioned massacre took place. Mercifully, your excursion is devoid of any encounters with the spectral residents whom the Assiniboine say haunt those grounds.

From 1869-1874, dozens of fur traders from Fort Benton, Montana, established quasi-legal trading posts in what is now Southern Alberta and Southwestern Saskatchewan and began trading goods to the local Blackfoot in exchange for buffalo robes. One of the chief commodities peddled at these forts was a rotgut concoction consisting of diluted whisky, tobacco, molasses, red ink, and other ingredients, which many Blackfoot found irresistible. The destructive effects of this whisky trade on the Blackfoot Nations was one of the major impetuses behind the creation of the NWMP.

It is dusk by the time you reach the Assiniboine camp, situated as it is at the edge of the open prairie. In typical Indian fashion, the Assiniboine have pitched their smoke-stained teepees in a large circle, in the centre of which they have tethered their horses as a precaution against potential Blackfoot horse thieves. Half-starved Indian dogs bark as you approach the camp, and shy Assiniboine children peek out from behind their mothers’ skirts as your red-coated companion hands sacks of flour to their grateful fathers and brothers.

“It is too dangerous for you to return home tonight,” the band’s chief says to the Mountie after the last of the provisions have been unloaded. “The ghosts don’t know the difference between Red Coats and wolfers. They will shoot you with their night arrows all the same. You had better stay in my lodge tonight.

The Mountie, having anticipated such a request, had already secured permission from his superior to spend the night in the Assiniboine camp. As your red-coated friend would have some difficulty communicating with his native hosts without you, you also accept the chief’s hospitality.

Later that night, you find yourself seated cross-legged on a buffalo robe in the chief’s teepee next to your red-coated friend, sharing a pipe with a handful of Assiniboine braves. Aside from the crackling of the buffalo chips in the centre of the lodge, which have been set ablaze to drive away the spring chill, and the distant, mournful howling of a pack of prairie wolves, all is quiet.

Once every man in the lodge has had the opportunity to smoke, your taciturn host breaks the silence. Using soft tones so as to not wake the women and children who are sleeping behind him, he and his men begin to converse in Plains Cree for your benefit and that of your white companion. The conversation ranges from the agreement which the Great White Mother hopes to make with the Cree and Assiniboine nations in the near future to the war being fought between the Sioux and the blue-coated Long Knives south of the Medicine Line.

When talk turns to the rumour that the great Sioux chief Sitting Bull hopes to make peace with the Blackfoot Confederacy, his people’s ancient enemies, an old grizzled warrior seated to your left begins fingering a greasy scalp lock stitched to the shoulder of his buckskin shirt. “It is a good thing that our people made peace with the Blackfoot,” he growls. “They were powerful enemies. Even if I live to see a hundred summers, I will never forget that battle on the Belly River. They shot us down like so many buffalo.” Without further ado, the old warrior launches into the tale of the world’s last great intertribal Indian battle, fought six years prior on the shores of a westerly waterway.

This hypothetical scenario serves to illustrate the manner in which James Francis Sanderson, the author of Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies, may have heard some of the tales he put to paper in 1894.

James F. Sanderson

James Francis Sanderson was born on March 23, 1848, in the fur trading town of Athabasca Landing, the site of the present-day town of Athabasca, Alberta, situated on the Athabasca River about 115 kilometres (72 miles) southeast of Lesser Slave Lake. His Scottish-Cree father, James Sr., worked aboard the Viking-style York boats of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), spending much of his time in York Factory, the Company’s headquarters, located on the southwestern shores of Hudson Bay. His mother Elizabeth, on the other hand, was the daughter of an Orcadian Scotsman named James Anderson- another HBC employee- and a Saulteaux woman named Mary.

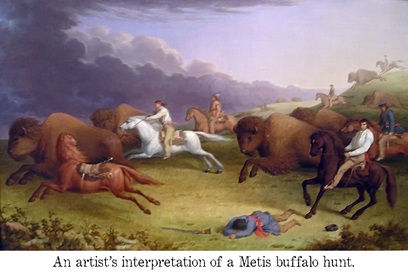

Shortly after taking up residence in the Red River Valley, James Sr. drowned in a boating accident on Lake Manitoba. James Jr. and the rest of his family subsequently relocated to the Metis village of Portage la Prairie to the northwest, where Elizabeth’s family, the Andersons, had also decided to resettle. In addition to receiving a basic formal education there, teenaged Sanderson accompanied the local Metis men on a number of buffalo hunts on the eastern prairies in the late 1860s, during which he acquired both an insatiable appetite for frontier life and perfect fluency in both French and Plains Cree.

In 1934, 1935, and 1936, George William Sanderson, James’ elder brother, recounted his childhood experiences to his niece, Mary Sophia Desmarais Campbell, who published them in a piece entitled Through Memory’s Windows. Of the Metis buffalo hunt, in which he was unable to participate on account of a childhood medical condition, George said:

In 1934, 1935, and 1936, George William Sanderson, James’ elder brother, recounted his childhood experiences to his niece, Mary Sophia Desmarais Campbell, who published them in a piece entitled Through Memory’s Windows. Of the Metis buffalo hunt, in which he was unable to participate on account of a childhood medical condition, George said:

“Buffalo meat was our chief article of food. Every summer for weeks at a time the settlers moved to the plains and killed buffalo, dried the meat and made pemmican of some of it. They sold the robes to the Hudson’s Bay Co. I have been told that when the hunter first began to chase the buffalo any old horse would do, but in later years one had to have a very swift horse. It took a good rider and a man had to be quick too to kill a buffalo. The guns were all muzzle loaders and the rider carried a powder horn on his right side, a shot or bullet pouch on the other, and the gun caps in his waist coat pocket. The bullets for immediate use he held in his mouth. The horses were well trained and could be guided by the motions and gestures, or leaning of the riders’ body…”

The Red River Rebellion

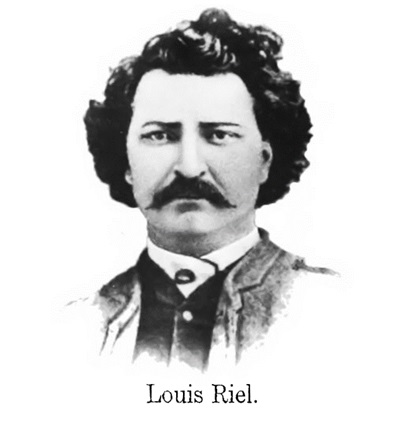

In the wake of Canadian Confederation (1867), a large force of French Metis from the Red River Valley refused a Canadian government survey party entry into the region, fearful that Dominion agents would force them to abandon their homesteads on the Red River, which they did not legally own, and relinquish their Michif language and Roman Catholic faith, to which they strongly adhered. Immediately after repelling the survey party, the Metis rebels seized Upper Fort Garry- an old HBC trading post situated at the site of what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba- completely without bloodshed. This uprising, called the Red River Rebellion, was led by a well-educated Metis revolutionary named Louis Riel.

In the wake of Canadian Confederation (1867), a large force of French Metis from the Red River Valley refused a Canadian government survey party entry into the region, fearful that Dominion agents would force them to abandon their homesteads on the Red River, which they did not legally own, and relinquish their Michif language and Roman Catholic faith, to which they strongly adhered. Immediately after repelling the survey party, the Metis rebels seized Upper Fort Garry- an old HBC trading post situated at the site of what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba- completely without bloodshed. This uprising, called the Red River Rebellion, was led by a well-educated Metis revolutionary named Louis Riel.

While Riel negotiated with Donald Smith- an HBC representative and future railway magnate who would come to be known as Lord Strathcona- hoping to transform the Red River Valley into a Metis province within the framework of the Dominion, fourty-eight pro-Canadian counter-revolutionaries, most of them of Scottish, Irish, or Anglo-Metis pedigree, plotted to overthrow the new provisional government that Riel had established. Before they could execute their scheme, however, they were arrested by Riel’s men and imprisoned at Upper Fort Gary.

Major Charles Boulton, a member of the Canadian government survey party that Riel had repelled, subsequently organized a militia with which to rescue Riel’s captives. Among the men he recruited were 20-year-old James Sanderson and his elder brother, George. Like the counter-revolutionaries before them, Boulton and his militia were captured by Riel’s Metis and imprisoned in Upper Fort Gary, where, according to the official history books, they languished in cold, cramped cells, forced to endure a month of privation and malnutrition.

Said George William Sanderson of the event of their capture:

“When we came near the Fort, a man on horseback shot out of the gate like an arrow, then another, and so on until ten or twelve came out. One rode towards us and stopped to speak. He held up a white handkerchief in his right hand… Old Mr. Pecha walked up to the rider and said in French, “Good day. What do you want?” The man answered, speaking in French also, “our leader, Louis Riel and his officers, wish you all to come into the Fort and have dinner with them.” Well, that was very acceptable. We wouldn’t dream of refusing such an invitation, as we had not too much to eat since we left home. We were all ushered into the Fort where we had to stay more than a month.”

Of their stay at Fort Gary, George Sanderson said:

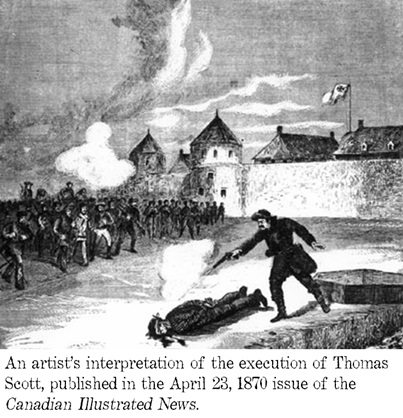

“We were all put into a large room to sleep. There were no beds, so we just bunked on the floor and benches. Most of us had a buffalo robe of our own. My brother Jim… and I slept together. We would have been quite comfortable had it not been for that man [Thomas] Scott making such a racket. He would kick the board partition, yell and curse, and was most impudent to the guard.

“One night when Scott was especially troublesome and noisy, a guard walked in and asked what all the trouble was about. He said, ‘Now you fellows had better be quiet. If I have to come in again tonight, I will bring a billy with me, and the man who is making the noise will get it over the head’.

“On the whole, we were used fairly well. We had all the pemmican we could eat, and tea to drink. The Frenchmen themselves had nothing else except that they had sugar in their tea, and we had none…

“The Roman Catholic priest made a special intercession for us to Riel and his guards. He asked them to use us as well as they could as we were just poor natives like themselves and it was not our fault we were captives…

“When we were in prison a few days, some of the town folk came in and asked Riel if they could supply us with one meal a day. Riel told them they could do so. They could give us whatever they wished. They raised a subscription among the inhabitants as the town was very small. They must have all given something, for after that we got one good meal a day, cakes, pies, bread, and butter and sugar for our tea.

“When we were in prison a few days, some of the town folk came in and asked Riel if they could supply us with one meal a day. Riel told them they could do so. They could give us whatever they wished. They raised a subscription among the inhabitants as the town was very small. They must have all given something, for after that we got one good meal a day, cakes, pies, bread, and butter and sugar for our tea.

“Some years ago, I picked up and began to read a history of the Manitoba Rebellion, the story told of the great hardships we endured as prisoners and how we were starved. It must have been written by someone who knew nothing about it, for it was nothing but a lot of damned lies. We were well-treated.”

During the Sanderson brothers’ imprisonment, one of their fellow pro-Canadian counter-revolutionaries- the troublesome aforementioned Thomas Scott, who was a staunchly Protestant Irishman- was executed by firing squad on Riel’s orders, apparently for the sole purpose of forcing the Canadian government to take the Metis seriously. The Dominion responded by sending a military expedition west to the Red River Valley to enforce peace in the region, prompting Riel to flee south to Dakota Territory in the United States and ending the Sanderson brothers’ month-long incarceration.

Heading West

In 1872, James Sanderson married Maria McKay, a Metis girl who belonged to a prominent Scots-Cree family. That same year, the McKay clan relocated to the Cypress Hills- a remote oasis nestled deep in the heart of the Canadian prairies, in the midst of a vast, wild, lawless domain known at that time as the North-West Territories. James Sanderson and his new wife accompanied their family west, where they lived the traditional Metis lifestyle, roaming the prairies in the summer months in search of buffalo and spending the winter in their cabin in the Cypress Hills, combatting hibernal monotony with music and dance. When they weren’t travelling or hunting buffalo, James and Maria helped Maria’s father, Edward, run the fur trading post that he established in the Cypress Hills.

In 1872, James Sanderson married Maria McKay, a Metis girl who belonged to a prominent Scots-Cree family. That same year, the McKay clan relocated to the Cypress Hills- a remote oasis nestled deep in the heart of the Canadian prairies, in the midst of a vast, wild, lawless domain known at that time as the North-West Territories. James Sanderson and his new wife accompanied their family west, where they lived the traditional Metis lifestyle, roaming the prairies in the summer months in search of buffalo and spending the winter in their cabin in the Cypress Hills, combatting hibernal monotony with music and dance. When they weren’t travelling or hunting buffalo, James and Maria helped Maria’s father, Edward, run the fur trading post that he established in the Cypress Hills.

The couple would go on to have four children: Caroline, Owen, Duncan, and Mary.

The Cypress Hills Massacre

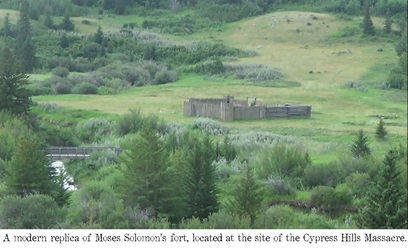

The Sandersons and the McKays were not the only fur traders plying their trade in the Cypress Hills at that time. Not far from their store were two rival trading posts separated by a small creek, one of them owned by a New York Polish-Jew named Moses Solomon and the other by a Montanan named Abe Farwell. Solomon and Farwell had both established their posts in 1871, having heard of the tremendous profits garnered by the traders at Fort Whoop-Up, an American-run fur trading post established in 1869 on the banks of what is now the Oldman River, about 215 kilometres (134 miles) to the west. The traders at Fort Whoop-Up had managed to acquire a prodigious quantity of buffalo robes through the practice of selling rotgut whisky to the local Blackfoot- a commodity for the procurance of which the natives would undergo any hardship. Hoping to replicate Whoop-Up’s success, Solomon and Farwell ensured that their stores were amply stocked with firewater.

The Sandersons and the McKays were not the only fur traders plying their trade in the Cypress Hills at that time. Not far from their store were two rival trading posts separated by a small creek, one of them owned by a New York Polish-Jew named Moses Solomon and the other by a Montanan named Abe Farwell. Solomon and Farwell had both established their posts in 1871, having heard of the tremendous profits garnered by the traders at Fort Whoop-Up, an American-run fur trading post established in 1869 on the banks of what is now the Oldman River, about 215 kilometres (134 miles) to the west. The traders at Fort Whoop-Up had managed to acquire a prodigious quantity of buffalo robes through the practice of selling rotgut whisky to the local Blackfoot- a commodity for the procurance of which the natives would undergo any hardship. Hoping to replicate Whoop-Up’s success, Solomon and Farwell ensured that their stores were amply stocked with firewater.

In the summer of 1873, twelve heavily-armed American wolf hunters rode up to Farwell and Solomon’s posts and generously helped themselves to the whisky traders’ eponymous wares. They informed their hosts that they were searching for an Indian raiding party which had stolen nineteen of their horses north of Fort Benton, Montana, several days prior, from whom they hoped to reclaim their animals. After engaging in idle banter with some of the forts’ employees, the wolfers became convinced that an impoverished band of Assiniboine Indians who were camped at the edge of the nearby creek were the horse thieves. The inebriated wolvers approached the Assiniboine camp with their rifles at the ready, prompting the natives, many of whom were similarly intoxicated, to take cover. Assuming that the Indians were preparing to fight them, the wolfers raised their guns and opened fire. After a brief exchange of gunfire, twenty-two Assiniboine- including several women and children- and one wolfer lay dead.

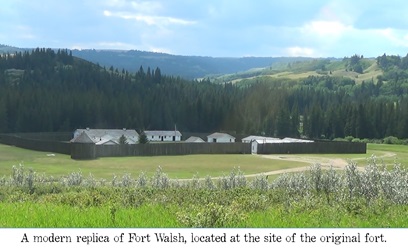

Fort Walsh

Since the year 1870, the Canadian government had been toying with the idea of sending a mounted police force west to suppress the illegal whisky trade in what is now Southern Alberta, the rumours of which they had learned from HBC employees stationed at trading posts along the North Saskatchewan River. Advocates of this western police force succeeded in passing a legislation allowing for the creation of the NWMP on May 23, 1873, coincidentally ten days before the aforementioned tragedy which has come to be known as the Cypress Hills Massacre. After learning of the bloody event, Canadian bureaucrats realized that they needed to form the police force quickly if they hoped to establish Canadian sovereignty on the western plains. The North-West Mounted Police was subsequently established, and less than a year later, its first officers made the long trek from Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, across the Canadian prairies to Fort Whoop-Up, located at the site of present-day Lethbridge, Alberta. A year later, the Mounties built Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills not far from the site of the massacre, in the vicinity of the McKay trading post.

Since the year 1870, the Canadian government had been toying with the idea of sending a mounted police force west to suppress the illegal whisky trade in what is now Southern Alberta, the rumours of which they had learned from HBC employees stationed at trading posts along the North Saskatchewan River. Advocates of this western police force succeeded in passing a legislation allowing for the creation of the NWMP on May 23, 1873, coincidentally ten days before the aforementioned tragedy which has come to be known as the Cypress Hills Massacre. After learning of the bloody event, Canadian bureaucrats realized that they needed to form the police force quickly if they hoped to establish Canadian sovereignty on the western plains. The North-West Mounted Police was subsequently established, and less than a year later, its first officers made the long trek from Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, across the Canadian prairies to Fort Whoop-Up, located at the site of present-day Lethbridge, Alberta. A year later, the Mounties built Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills not far from the site of the massacre, in the vicinity of the McKay trading post.

James Sanderson found work with the Mounties as soon as they established themselves in the area, serving the Force as a scout, hunter, and interpreter. The farsighted frontiersmen realized that, with the coming of the Mounties, the days of Canada’s Wild West would rapidly draw to a close. Cognizant of the possibility that the buffalo, which had dominated the North American Plains since time immemorial, might not be around forever, Sanderson rode south to Montana, purchased a small herd of cattle at the town of Fort Benton, and drove his livestock north to the Cypress Hills.

In 1878, Fort Walsh was made the new headquarters of the North-West Mounted Police (the former being Fort Macleod, built upriver from Fort Whoop-Up), its importance having been bolstered by the presence of Sitting Bull’s Sioux, who had fled into Canada and settled at easterly Wood Mountain following the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The influx of policemen to the new headquarters led to Sanderson’s acquiring a lucrative contract selling beef to the Mounties, through which he accumulated a small fortune.

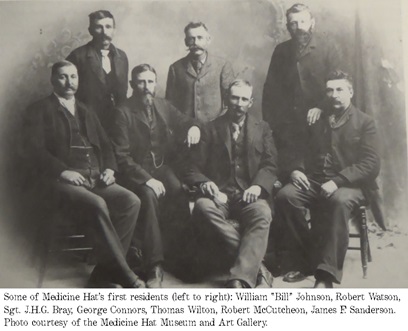

Medicine Hat

In 1882, the NWMP headquarters was moved to the fledgling town of Regina, newly-established at a location to the east hitherto known as ‘Pile-o’-Bones’. The Sanderson and McKay families subsequently left the Cypress Hills and resettled at a lonely stretch of riverbank which the Indians called “Saamis”, or “Medicine Hat”, located about 80 kilometres (50 miles) to the northwest on the shores of the South Saskatchewan River. The frontiersmen knew that the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR)- Canada’s first trans-Atlantic railroad- was to cross the South Saskatchewan River at Medicine Hat, and surmised that the CPR worksite would grow into a thriving community. Sure enough, when the CP Railway reached Medicine Hat in 1883 and construction of the bridge over the South Saskatchewan commenced, a town sprang up in the vicinity of the work camp.

In 1882, the NWMP headquarters was moved to the fledgling town of Regina, newly-established at a location to the east hitherto known as ‘Pile-o’-Bones’. The Sanderson and McKay families subsequently left the Cypress Hills and resettled at a lonely stretch of riverbank which the Indians called “Saamis”, or “Medicine Hat”, located about 80 kilometres (50 miles) to the northwest on the shores of the South Saskatchewan River. The frontiersmen knew that the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR)- Canada’s first trans-Atlantic railroad- was to cross the South Saskatchewan River at Medicine Hat, and surmised that the CPR worksite would grow into a thriving community. Sure enough, when the CP Railway reached Medicine Hat in 1883 and construction of the bridge over the South Saskatchewan commenced, a town sprang up in the vicinity of the work camp.

James Francis Sanderson quickly established himself as one of Medicine Hat’s most prominent citizens, working variously as a freighter and general contractor for the CPR, a buffalo bone collector (due to their high phosphorous content, buffalo bones were used to make fertilizer at that time), an interpreter for the local Mounties, an agent for a local coal mine, and a regional wolf inspector. Eventually, Sanderson operated a bull herd for local cattlemen, herding bulls from the surrounding ranches onto his own property every spring and fall. Later on, he established his own livery herd and his own cattle ranch on a flat bordering the South Saskatchewan River, which came to be known as Sanderson’s Point, and became an ardent proponent of horse racing.

In 1894, James Sanderson wrote a series of articles for the Medicine Hat News entitled “Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies”, in which he recounted some of the stories he heard from his Metis and First Nations friends during his days as a trader and buffalo hunter on the Western Canadian frontier. Most of these stories appear to be based on events which took place from 1850-1870.

In 1894, James Sanderson wrote a series of articles for the Medicine Hat News entitled “Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies”, in which he recounted some of the stories he heard from his Metis and First Nations friends during his days as a trader and buffalo hunter on the Western Canadian frontier. Most of these stories appear to be based on events which took place from 1850-1870.

In 1896, Sanderson sent a shipment of cattle across the continent and the Atlantic Ocean beyond to England. A reporter for the Montreal Herald who encountered him during this journey described him as “a stalwart Scotsman with the frame of a Hercules, and the suspicion of a strain of the Cree chieftain’s blood in his bearing”.

James Francis Sanderson passed away in Medicine Hat, Alberta, on December 8, 1902, at the age of 54, leaving behind four children, a foster daughter, and an invaluable piece of Canadian literature offering a unique glimpse into the history, folklore, and character of Canada’s Wild West. He was buried in Medicine Hat’s Old Hillside Cemetery, where he lies today beside his wife and his son, Owen.

In the summer of 1965, Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies was republished in the Alberta Historical Review, supplemented with eight excellent illustrations by Calgary-based artist William B. Fraser. That same year, the piece, complete with Fraser’s illustrations, was republished by the Historical Society of Alberta.

Sources

- “Sanderson, James Francis” (2003), by L. J. Roy Wilson in Volume 13 of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- The Andersons: A Hudson’s Bay Company Family (ca. 1985), by Theresa Schenk

- James F. Sanderson (1957), by E.G. Luxton; from the Southern Alberta Research Project

- Through Memory’s Windows, as told to Mary Sophia Desmaris Campbell by her uncle George William Sanderson in 1934, 1935, 1936

- RedRiverAncestry.ca

- “About the Author” section of the 1965 publication of James F. Sanderson’s Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies, issued by the Historical Society of Alberta

Leave a Reply