The following article was originally published on my personal website in 2014.

The Whisky Trade in Canada

There is a custom, as ancient as it is universal, in which an international traveler presents his host with a gift epitomical of his home country. In accordance with this practice, Canadians, while travelling abroad, often bring typical “Canadian” gifts– such as maple syrup, toques or hockey sticks- for their foreign relatives, tour guides, business associates, etc. One of the most classic of these Canadian gifts is a bottle of premium Canadian rye whisky, like Crown Royal or Canadian Club. Although we Canadians certainly have a right to take pride in our indigenous whisky, we also have a responsibility to remember its infamous predecessor, a beverage termed “firewater” by the Indians, and the ruinous effect it had upon Canada’s First Nations.

Origin

This embarrassing chapter of Canadian history- comparable to Canada’s residential schools, Eskimo disc numbers and Japanese internment camps- has is origins in the North American fur trade. Initially, the North American fur trade was dominated by two major companies: the English-owned Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC; established in 1670); and the Gallic Montreal-based North West Company (NWC; formed in 1779). These two businesses competed to supply beaver pelts and other furs to top-hat-wearing and fur-coat-bearing Europe. They typically acquired their furs by trading with the First Nations, who had been hunting and trapping fur-bearing animals for millennia.

Since the inception of the NWC, Quebecois fur traders used liquor as both a trading commodity and as a gift to incentivise fur-bearing Indians to trade at their forts and to cement already-existing trade relations. The HBC eventually followed suit in order to successfully compete with its opposition, as did the United States-based American Fur Company (AFC) upon its founding in 1808 (several decades after the American Revolution).

The HBC and NWC typically dealt in rum and brandy, so-called “high wines” which were imported from Europe. When the large barrels of spirits arrived at their destinations, the company men heavily diluted them with water, usually in a 7:1 ratio, and transferred the mixture into skin bags or small kegs before offering it to the Indians. The spirits usually arrived in huge bi-annual shipments- one in the spring and another in the fall- and subsequently the HBC and NWC only sold their alcoholic wares twice a year.

By the early 1800’s, the procedure of these biannual sales had become well established. Typically, a couple of Indian runners would arrive at a fur trading post to announce the arrival of a band. These messengers were treated with liquor and pipe tobacco. After the band arrived, the chiefs were invited into the fort and plied similarly. Then the chiefs were presented with the skin bags and small kegs that the company had prepared. The chiefs took the alcohol back to camp, where it was all promptly consumed. In ensuing carousal, in which knives were drawn and guns were fired, accidental deaths were not uncommon. The next morning, when the Indians were sufficiently sober to conduct business, the main trading took place. Although liquor was among the European commodities sold, most furs were exchanged for firearms, metal implements, woolen blankets and other such items.

Over time, these biannual liquor distributions, while infrequent, slowly drew a number of First Nations people into alcohol dependency. Their sad legacy is painfully conspicuous even today.

The British parliament was cognisant of the damage the liquor trade had upon the Indians and continually tried to suppress it. In 1822, one year after the NWC and HBC were amalgamated as the HBC, the company, under pressure from the parliament, passed a resolution to half the volume of liquor that was distributed at the biannual events. In 1825, the HBC endeavored to gradually discontinue the liquor distribution/trade entirely, but succeeded only in banning liquor as an item for sale (it continued to be issued as gifts). In 1836, the HBC again passed a regulation to gradually discontinue the liquor distribution. However, the American AFC, which distributed liquor freely, had gained a foothold in the Upper Missouri region, and would later move up the Missouri to establish Fort Benton, the future economic centre of the Great Plains throughout the 1850’s, ‘60’s, and ‘70’s. With this new southern competition, the HBC feared it would lose business, and so it convinced the British parliament to allow it to continue to issue diluted rum and brandy to the Indians. The HBC and British parliament worked to slowly reduce the flow of alcohol, however, until finally, on December 1862, the HBC issued its last keg of diluted rum at Edmonton House.

The Montanan Invasion

Meanwhile in America, the fur trade had degenerated into a dangerous and unscrupulous industry. The AFC met its demise in 1847, and with it the good relations that had been forged between the American Indian and the white man in the early days of the fur trade. Smaller trading firms, such as I.G. Baker, T.C. Power, Carroll & Steel, and the North West Fur Company, along with independent wagon-back traders, quickly formed to fill the vacuum, being far more calloused towards the plight of the Indians than the monopoly which they replaced. Instead of selling diluted rum or brandy to the Indians, these traders peddled rotgut pseudo-whisky adulterated with toxic substances like sulfuric acid, turpentine, strychnine (a poison used by wolfers; modern day rat poison), cocculus indicus (a southeast Asian poison used as a pesticide and delousing agent) and tobacco. Their dishonest business practices led to many bloody altercations with the local Indians, especially with the Montanan South Peigans around the Fort Benton area. A series of these deadly conflicts between white Montanans and South Peigans, attributable in part to the whiskey trade, that took place throughout the 1860’s are known collectively as the “Blackfoot wars”. These so-called “Blackfoot wars” culminated in the Marias Massacre of 1870, a slaughter of nearly 200 friendly South Peigans- mostly women, children and elderly men- conducted by the U.S. Army (an event which compelled Mountain Chief and his band of South Peigan to travel north to present-day Lethbridge, just in time for the Battle of Belly River).

In the aftermath of the Blackfoot wars, the related northward diaspora of South Peigan, the subsequent federal crackdown on American whisky traders and a small unrelated gold rush in the Porcupine Hills, Montanan traders began to turn their gaze north of the 49th parallel. The first American traders to jump through a series of federal loopholes, travel north to make the first wagon ruts on what would become the Old Macleod Trail (with the help of a trading party, one of the members of which was Jerry Potts), and establish a trading post in Canada (at that time “Rupert’s Land”) were John J. Healy and Alfred B. Hamilton, who established Fort Hamilton (more popularly known as Fort Whoop-Up) on the shores of the Oldman River in 1869 in what would become the city of Lethbridge.

After Fort Whoop-Up’s enormous financial success in 1869, ’70 and ’71, other American traders followed Healy and Hamilton’s example and, after receiving permits from the United States government to “pass through Blackfoot Country… and across the northern boundary line of the United States… for the purpose of exploring and prospecting the country,” brought wagonloads of whisky into Canada for the actual purpose of sale to the local Blackfoot. Almost every party of these traders set up a trading post on the Belly (now Oldman) River, where many Blackfoot bands camped in the winter. Among the first of these traders were Joe Kipp and Charlie Thomas, who established Fort Standoff (and later Fort Kipp) after engaging in a standoff with United States Deputy Marshall Hard near the American-Canadian border.

The flood of American whisky traders into Canada, and the commerce that came with them, was disastrous for the local Indians. In the space of a few short years, the mighty Blackfoot Confederacy that had dominated the western Canadian plains, the members of which’s sole occupations since time immemorial had been hunting, warfare and family life, was transformed into a nation of alcoholics who would “undergo every hardship and fatigue to procure a [cupful of whisky].”

The Montanan whisky trade in what would become southern Alberta not only destroyed the livelihood of the local Indians but also decimated their population. In the drunken revelries that followed whisky transactions, many Indians were killed by errant (or deliberately aimed) bullets and knives. Others fell victim to the whisky itself, or passed out from the alcohol and froze to death overnight. In the words of Crowfoot, head chief of the Siksika Blackfoot:

“The whiskey brought among us by the Traders is fast killing us off and we are powerless before the evil. [We are] totally unable to resist the temptation to drink when brought in contact with the white man’s water. We are also unable to pitch anywhere that the Trader cannot follow us. Our horses, Buffalo robes and other articles of trade go for whisky; a large number of our people have killed one another and perished in various ways under the influence.”

Doubtless the whisky traders were well aware of the effect their wares had upon their clients. If some sources are to be believed, some of the traders believed they were doing the world a service. In the words of Frank Wilkeson, a journalist for the New York Sun who visited southern Alberta in the summer of 1871, “Far from being an injury to the United States, [the whisky traders] said they were a great benefit as they keep the Indians poor, and kill directly or indirectly more Indians of the most warlike tribe on the continent every year, at no cost to the United States government, than the more regular army did in ten years!” Another journalist mentioned the traders’ apparent indifference to the effects of their trade, stating that they, “appear to have been singularly oblivious to the effects that their whiskey was producing just outside their doors… The whiskey trader would coolly close the heavy gates of his stockade, and sitting down safely and comfortably inside the fort, have no more concern at the rattle of firearms outside, the shouts of the victors, and the shrieks and moans of the wounded and dying, than he would to the snarling and howling of a band of coyotes fighting over the remains of a dead buffalo.”

In the season of 1872/73, a number of whisky traders left the Oldman River Valley to establish posts along the Highwood, Elbow and Bow Rivers, and in the easterly Cypress Hills in order to trade with the Assiniboine. With limited American intervention and no Canadian law enforcement, the whisky traffic flourished. Said an article in the Helena Daily Herald of the ‘72/’73 season, “the wretched whisky traders who ply their nefarious traffic across the line separating the Territory from the British Possession, bringing back the robes and peltries bartered by the savages for the white man’s ‘fire water’. This traffic is calamitous.”

The Formation of the North West Mounted Police

In October 1870, the Canadian government outlawed the sale of alcohol in Rupert’s Land (a territory with dynamic borders which, at that time, included most of present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta). In order to inform frontier missionaries and Hudson’s Bay Company employees of the prohibition, the Canadian government immediately dispatched Lieutenant William F. Butler to the HBC trading posts along the North Saskatchewan River.

Throughout the course of his journey, which took him as far west as Rocky Mountain House, Butler discovered that Metis entrepreneurs from the Red River Valley in the newly-formed Province of Manitoba had been trading whisky to the Cree and Siksika Blackfoot inhabiting the land just south of the North Saskatchewan HBC posts since the early 1860’s. These free traders carted their wares- barrels of American alcohol imported from Minnesota Territory- up the western shore of Lake Winnipeg, along the Saskatchewan and antecedent North Saskatchewan Rivers, and into the area just south of the HBC posts. Butler also heard rumors, brought to the HBC posts by Indians and missionaries (such as pseudo-priest Jean L’Heureux, who features prominently in the tale of the Lost Lemon Mine), that Americans from Fort Benton had established heavily-armed whisky forts along the Belly River. Upon his return to Ottawa, he relayed this disquieting information to his superior, Lieutenant-Governor Adams G. Archibald, and suggested that a cavalry regiment be sent west to enforce the prohibition in the Fort Saskatchewan area and stem the Montanan trade in the south. Archibald further relayed this mission to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.

Instead of dispatching a cavalry regiment, Macdonald sent another agent, Colonel Peter Robertson-Ross, to verify Butler’s claims. Robertson-Ross, like Butler, travelled to Rocky Mountain House, and then continued through the Crowsnest Pass to the West Coast, effectually (albeit unintentionally) bypassing the illegal whisky forts. After returning to Ottawa, however, he similarly suggested military intervention to the Prime Minister. In spite of Robertson-Ross and Butler’s suggestions, however, Macdonald made no move mobilize a western police force.

It took the Cypress Hills Massacre of June 2, 1873, to catalyze a Canadian response to the illegal whisky trade. After a long-drawn-out bureaucratic battle with Canadian and British officials advocating the formation of a western police force, Macdonald finally conceded, and on July 8, 1874, the first of the newly-established North West Mounted Police departed Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, and began their famous march west.

The End of the Whisky Trade

The whisky traders in what would become southern Alberta were forewarned of the Mounties’ coming. Many of them, upon hearing the news, became legitimate traders and eliminated whisky from their stock. Others returned south and sold their whisky on the Montana Blackfoot Reservation, where law enforcement was scant. The remainder- among which was Harry “Kamoose” Taylor, future owner of the Macleod Hotel in Fort Macleod– chose to continue selling whisky to the Indians from their Canadian forts.

The North West Mounted Police arrived in the Canadian west in the fall of 1874 and, after hiring Scots-Peigan scout Jerry Potts in Fort Benton, Montana, made their way to Fort Whoop-Up, the heart of the Canadian whisky trade. The traders at Fort Whoop-Up were prepared for the Mounties’ arrival, and had cached all their contraband. Upon searching the fort, the Mounties found no cause to condemn it. After inspecting another whisky fort with similar results, the North West Mounted Police reached an island on the Oldman River, where they built their headquarters, Fort Macleod.

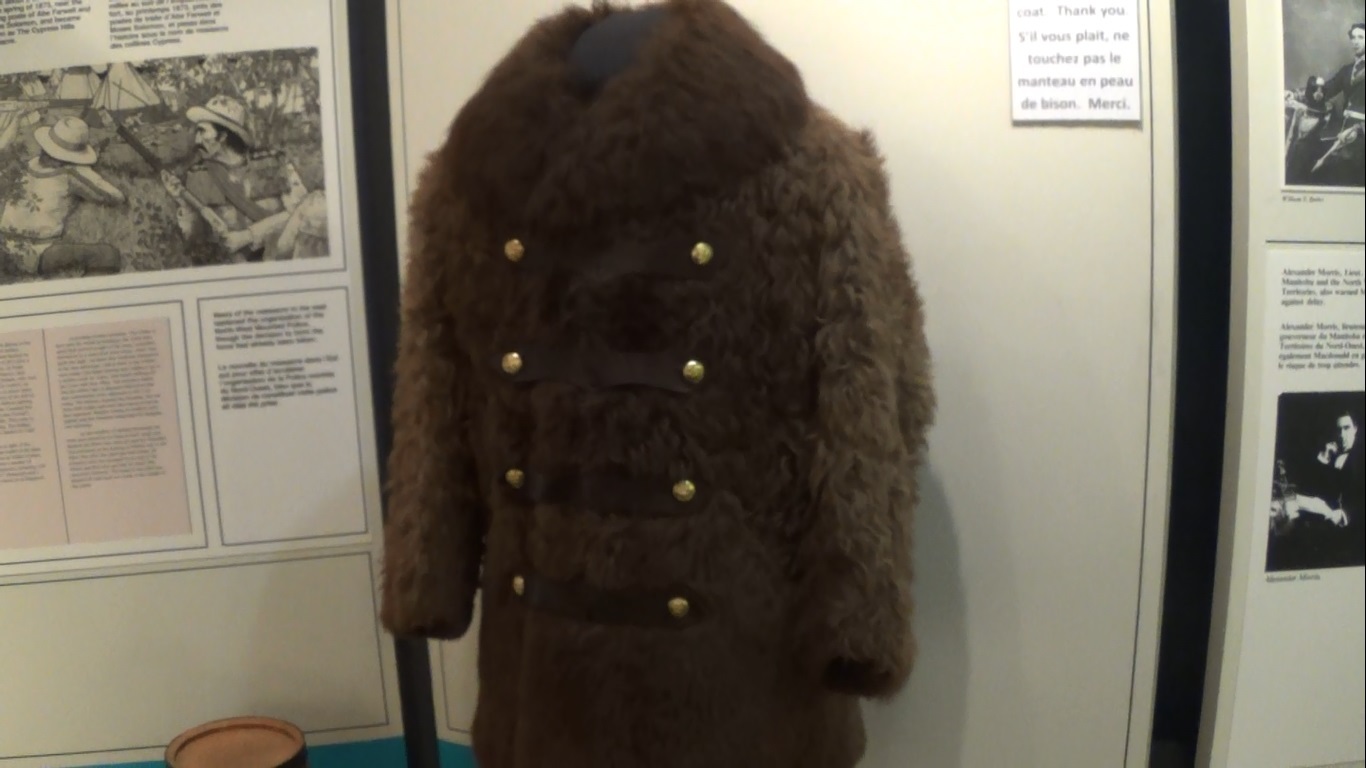

That winter, the Mounties arrested a number of whisky traders- including Harry “Kamoose” Taylor- seized and destroyed large quantities of American whisky, and levied heavy fines for whisky trafficking, which were paid in buffalo robes- the only real currency in the area, aside from whisky, horses and ammunition, which the Mounties subsequently used to make winter coats for themselves. The Mounties’ efforts culminated in the trial and conviction of J.D. Weatherwax, a prominent whisky trader in the area, who was subsequently fined three hundred dollars and imprisoned for six months. Although Weatherwax’s arrest and conviction was of questionable legality, based as it was on sketchy and circumstantial evidence, it nonetheless ended the majority of whisky traffic in southern Alberta.

Source

- Firewater, 2002, Hugh A. Dempsey

Leave a Reply