5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West

Back to 5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West

1. Jerry Potts

When the sun-burnt, mosquito-bitten officers of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) rode into Writing-on-Stone in the fall of 1874, they were disheartened, saddle-weary, and lost. The previous winter, they had first come together as a unit in Fort Dufferin, Manitoba. That summer, after months of training, they rode out west bound for the notorious Fort Whoop-Up, determined to bring law and order to the Canadian Wild West. Unfortunately, some of the Metis guides they hired had a less than complete knowledge of the western territory’s geography. By early fall, the Mounties found themselves straddling the Boundary Commission Trail on the Canadian-American border with no idea where they were in relation to their destination, Whoop-Up Country.

The Force’s Assistant Commissioner James Macleod and a handful of officers rode south to Fort Benton, Montana, in the hopes that they might find some directions. They found better. Two of the town’s most prominent businessman hosted the Mounties. During dinner, the Montanan merchants suggested that Macleod and company hire a short, bowlegged Scots-Blackfoot frontiersman named Jerry Potts as their guide. Despite learning that the unimposing mustachioed plainsman was a man of few words who had an enormous appetite for whisky, the commodity which they hoped eliminate from the Canadian plains, the Mounties took their suggestion and hired Jerry Potts as their chief scout. They couldn’t have been happier with their decision.

Jerry Potts returned with Macleod to Writing-on-Stone, took up a position at the head of the column, and led the bedraggled Mounties northwest over prairies and coulees. Said Mountie Sam Steele of the quiet, mysterious guide, “he never talked with others when he was at work. He would ride on ahead by himself, keeping his mind fixed on the mysterious business of finding the way. He was never able to give any clear explanation of his method. Some mysterious power, perhaps a heritage from his Indian ancestors, was at work.” In no time, Potts led the Mounted Policemen to Fort Whoop-Up, on the banks of the Oldman River. Shortly thereafter, he led them upriver to the location at which they would build Fort Macleod, their first permanent headquarters.

In the ensuing months, Potts, who was fluent in a number of Indian languages, also served the Mounties as an interpreter and Indian ambassador. While the Policemen were building Fort Macleod, he traveled throughout the territory to speak with the local Blackfoot chiefs, on whose lands the Mounties encroached. Potts informed the chiefs that the red coats were there to suppress the whisky trade which had brought the Blackfoot people so much grief, and that they had their interests at heart. The officers who accompanied Potts on these excursions noticed how the powerful Blackfoot chiefs treated the wiry half-breed with deference and respect and took him at his word. The scout, they soon realized, was well-known and highly respected among the people of the plains.

Over the years, various Mounties got the taciturn frontiersman to open up and reveal his mysterious past, which, if the manner in which the Blackfoot treated him was any judge, had evidently earned him a ferocious reputation throughout the Canadian-American plains. As it turned out, Jerry Potts was a man of two worlds. He spent half his time among his father’s people, the predominantly-white traders and ranchers of Fort Benton, Montana, working for various fur trading companies. While at the Fort, one of his favorite past-times was to fortify himself with whisky before playing a gutsy game with his co-worker and fellow half-breed George Star, in which the two of them, armed with revolvers, would stand 20 paces apart and literally trim each other’s mustaches with bullets.

In the white man’s world, Jerry Potts’ primary function was that of a scout. As a result, he often found himself far from the Fort in hostile Sioux territory. One time, while on a scouting expedition with two white men, Potts and his charges were set upon by a war party of about 200 well-equipped Sioux braves. At first, the half-breed ordered his charges to flee on horseback. When he realized that some of the warriors mounted on faster horses would inevitably catch up to them, however, Potts suddenly ordered his two clients to wheel around and ride through the Sioux ranks. After passing through the horde unscathed, Potts had his clients take shelter in a nearby abandoned cabin, where he, armed with nothing more than a revolver, managed to fend off the enterprising braves who rushed their location. That night, after sneaking into the Sioux camp and stealing three of their best horses, Potts and his two charges rode back to the Fort, escaping certain death.

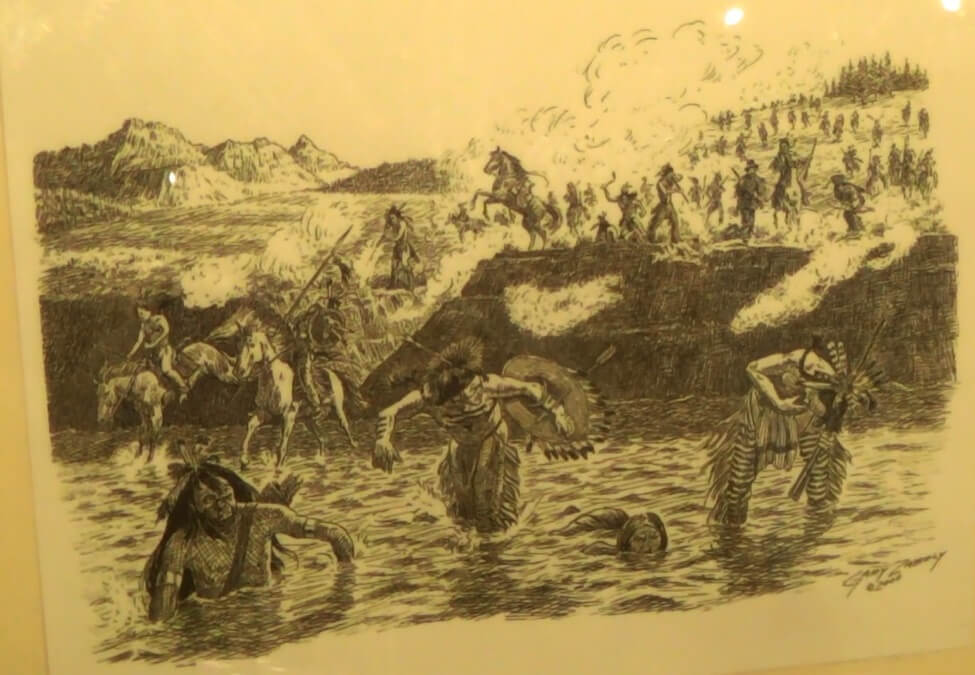

When he was not working for the fur traders of Fort Benton, Jerry Potts lived among his mother’s people, the Blackfoot. He participated wholeheartedly in various raiding parties and war parties against the Sioux, Crow, Shoshone, Cree, and Assiniboine, and quickly established himself as a formidable warrior and horse thief. On October 25, 1870, Potts participated in the Battle of Belly River, the last great battle between the Blackfoot and Iron Confederacies and the last great inter-tribal Indian battle in the world. It was due to Potts’ leadership that the Blackfoot were able to take advantage of a Cree-Assiniboine retreat, turn the tide of the battle in their favour, and completely route their enemies. Due to his martial prowess, and the fact that he, despite his extensive combat experience, was never wounded in battle, the Blackfoot began to regard him with superstitious awe. Potts himself was imbued with the superstitious nature of a Blackfoot and, due to instructions he received in a dream, wore a catskin amulet around his neck day and night for good luck.

In 1869, Jerry Potts guided John Healy, Alfred Hamilton, and a handful of American whisky traders from Fort Benton to a place on the Oldman River. There, the whisky traders built Fort Whoop-Up, the notorious whisky fort which’s calamitous traffic, in essence, became the main reason for the formation of the North West Mounted Police. Throughout he early 1870’s, Potts watched in horror as the Canadian whisky trade, which he helped establish, succeeded in all but destroying his mother’s people, the Blackfoot.

In the spring of 1872, Potts’ mother and brother were killed in a whisky fueled argument. When Potts received word of the incident, he avowed to avenge their murders. About two months later, while watering horses near a Canadian whisky post called Fort Kipp, Potts spotted his mother and brother’s murderer riding out from the fort. The half-breed, furious, pursued the Indian and killed him just a short distance from his own camp.

Following the death of his mother and brother, Potts sought an end to the whisky trade, and was more than happy to assist the Mounties when they rode into Fort Benton in search of a guide.

After joining the Mounties, Jerry Potts performed the functions of scout and interpreter. By all accounts, he was a magnificent scout, and an abysmal interpreter. In the winter of early 1875, he led his respective Mountie charges through blizzards on two different occasions, during one of which he was rendered snow-blind. Said Sam Steele of his scouting ability,“he possessed an uncanny sense of locality and direction. Others could guide travelers through country they had visited before, but this man could take a party from place to place by the quickest route, through country altogether unknown to him, without compass and without sight of the stars.” On the other hand, during the signing of Treaty 7, during which the Blackfoot Nations made an agreement with the British Crown, Potts served as interpreter between the Blackfoot chiefs and Government of Canada representatives… that is, until called upon to translate Governor of the North-West Territory David Laird’s eloquent speech into Blackfoot. Potts, a man of limited frontier vocabulary, had no idea what the well-educated governor was saying, and said as much when called upon to interpret.

As a scout and Indian ambassador, Jerry Potts proved to be an invaluable asset to the Mounties. However, his love of whisky often strained his relationship with his superiors. For example, during the early days of the suppression of the whisky trade, Potts and a few officers of the NWMP accosted a pair of bootleggers smuggling whisky across the 49th parallel. The half-breed, who was tasked with keeping an eye on the prisoners in the back of their wagon, broke into the contraband and shared it with the men he was supposed to be guarding. In the words of Constable Robert Wilson, one of the Mounties who accompanied Potts on this mission, “the two prisoners and Jerry were soon howling drunk…” The three men promptly quaffed all the evidence of their wrongdoing, much to the displeasure of Potts’ superiors once they got wind of the incident.

During the North-West Rebellion of 1885- fomented by Metis revolutionary Louis Riel; in which the Metis people of the Red River and Qu’Appelle Valleys, and their Cree and Assiniboine allies fought against the Canadian government- Jerry Potts served as a peacemaker. While Metis and Cree ambassadors rode into Blackfoot reserves imploring their old enemies to take up arms with them against the Canadian government, Potts reminded his Blackfoot friends of their century-long feud against the Cree and Metis, and the good decade-long relationship they had enjoyed with the North-West Mounted Police. Due in part to Potts’ efforts, the Blackfoot refrained from joining the rebellion, thereby preventing what would likely have a huge amount of bloodshed. In the words of North-West Mounted Police physician Dr. George Allan Kennedy, “had the Blackfeet forgotten their own enmity and joined hands with the Crees, it is hardly possible to calculate the enormous loss of life and property that would have followed…”

On July 14, 1896, 56-year-old Jerry Potts succumbed to throat cancer, which was likely attributable, at least in part, to his life of hard drinking. This paragon of the Canadian Wild West was buried in the North-West Mounted Police cemetery in Fort Macleod with full military honours. His obituary in the Fort Macleod Gazette reads:

“Jerry Potts is dead. Through the whole North West, in many parts of eastern Canada, and in England itself, this announcement will excite sorrow, in many cases sympathy, and in all, interest. His memory will long be green in the hearts of those who knew him best, and ‘faithful and true’ is the character he leaves behind him- the best monument of a valuable life.”

5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West:

3) John Healy

4) Joe Kipp

5) Harry “Kamoose” Taylor

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

Josephine Staddon

Very interesting article especially as the name “Potts” is still common among indigenous people. My niece Rachel Potts is an example although she is Cree. While I realize vocabulary has evolved a great deal over the years I still find it insulting that nouns such as “half breed” are still used. The article states that Pott’s father was Scots and his mother Blackfoot is that not enough to surmise that Potts had mixed blood?

Half-breed then, as now, is derogatory. Please revise your nouns.

Thank you.

Hammerson Peters

I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The word ‘half-breed’ certainly wasn’t insulting in Potts’ day, and I did not intend it as an insult in this article. It is the only accurate word for his heritage. ‘Metis’ might be more palatable, but would be inaccurate in Potts’ case.

Gerry Burnie

Bravo, to author Hammerson Peters and Mysteries of Canada for the type of history that should be taught in schools.

Yes, it is important to extol the accomplishments of John A., and the various dates and events that dot Canadian history, but if young people – boys in particular – are going to be drawn to history, it should have some ‘meat’ to it.

This is my first discovery of Mysteries of Canada, but I will definitely be coming back.

Bravo, once again!

Hammerson Peters

Thank you so much for your kind comment, Gerry! I totally agree; Canadian school curricula tend to totally desiccate subjects, like local history, that have the potential to be very interesting.

wayne

I think the year was 1870 not 1970

Hammerson Peters

Haha good call!