5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West

Back to 5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West

3. John J. Healy

Every good western story needs its heroes and villains. If the history of the Canadian Wild West was dramatized in print or film, the officers of the North West Mounted Police would almost certainly be the good guys, while Montanan whisky traders would probably be the bad guys. Undoubtedly, the most powerful and prolific of the Montanan whisky traders to ply his trade north of the border- indeed the man who first brought American firewater to the Canadian plains in 1869, the man who might quite justifiably be considered the arch-nemesis of the early North West Mounted Police- was a fearless, wiry Irishman named John J. Healy. As is the case with all characters of the Canadian Wild West, however, John Healy was neither all bad, nor all good, but rather a bit of both.

John Jerome (or perhaps Joseph) Healy was born on January 24, 1840 in Bandon, County Cork, Ireland, into a family of millers. Like his Canadian-American Wild West counterpart Kootenai Brown, his childhood was dominated by the horrors of the Great Famine which ravaged Ireland in the latter half of the 1840’s and early 1850’s. Although John Healy, in latter-life reminiscences, would talk openly about his exploits on the Canadian-American frontier, he remained understandably tight-lipped about his early life in Ireland.

In the winter of 1853, John’s father Thomas decided that it was in his family’s best interests to leave the Old World for the New. Together with both his parents, his five siblings, and a flood of fellow Irish immigrants, 13-year-old John travelled across the Atlantic to New York City. His mother died shortly upon arriving in America and his father quickly remarried, prompting John to leave his father and siblings and take to the streets. According to some historians, Healy, not finding New York street life to his liking, left the city shortly thereafter and enlisted in the irregular freebooting army of American filibuster William Walker. If true, Healy would almost certainly have accompanied Walker and his soldiers to Nicaragua, where the mercenary army ultimately succeeded in capturing the city of Granada, effectively taking control of the Latin American country at the height of a political revolt.

Although historians are divided on whether or not John Healy really joined the mercenary army of William Walker in 1854, they generally agree that he eventually wound up in Buffalo, New York, where, in the spring of 1858, he enlisted in the Second Dragoons of the U.S. Army. The eighteen-year-old Irishman lied about his age in order to join the Force, declaring that he was “21 years and two months of age” (at that time, the U.S. Army accepted soldiers no younger than 21). He also declared that he had spent the past few years apprenticing in the saddlery trade. After completing basic training at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Healy was dispatched to Camp Floyd, a U.S. Army post about 60 kilometres southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah. There, he and his company relieved the post’s garrison in the aftermath of the so-called ‘Utah War,’ a conflict between Mormon settlers of Utah Territory and the Washington government.

After doing garrison duty at Camp Floyd, Healy was posted in the Rocky Mountains to the west. There, he was tasked with patrolling a stretch of the wagon-rutted Oregon Trail, a settler trail which connected the American West Coast with the Missouri River. It was in the American Rockies that the eighteen-year-old soldier got his first taste of the western frontier, participating in Cheyenne buffalo hunts and meeting paragons of the American West like adventurer John Wesley Powell and legendary mountain man Jim Bridger. By 1860- when he was discharged from the Army on account of the War Department’s discovery of his true age- John Healy had fallen in love with the American Wild West.

Immediately upon his discharge, John Healy decided to prospect for gold. Instead of following in the wake of the Fifty-Niners- the hoard of prospectors who flocked to Kansas and Nebraska Territory in 1859- and pan the creeks of Pike’s Peak Country for gold, however, he decided to travel to what is now Clearwater County, Idaho, where gold had  been discovered that year. In order to earn his passage to the goldfields, he traded in his blue coat for buckskins and hired himself out as a guide to a wagon train traversing the Oregon Trail. En route to its destination, the wagon train was constantly harried by Shoshone warriors. Healy, being the only member of the train with anything approaching frontier experience, found himself thrust into a position of unofficial authority. Through the use of wit, nerve, and sheer dumb luck, Healy managed to guide the wagon train safely through hostile Indian territory, earning himself an ample paycheck and an arrow wound in the leg.

been discovered that year. In order to earn his passage to the goldfields, he traded in his blue coat for buckskins and hired himself out as a guide to a wagon train traversing the Oregon Trail. En route to its destination, the wagon train was constantly harried by Shoshone warriors. Healy, being the only member of the train with anything approaching frontier experience, found himself thrust into a position of unofficial authority. Through the use of wit, nerve, and sheer dumb luck, Healy managed to guide the wagon train safely through hostile Indian territory, earning himself an ample paycheck and an arrow wound in the leg.

John Healy used his the money he earned to outfit himself in Portland, Oregon, and purchase steamboat tickets up the Columbia River to the Idaho goldfields. While on the trail, he partnered up with John Kennedy, a railroader and fellow ex-soldier from Ohio, along with a handful of prospectors from Portland. The company reached their destination with little incident, did some panning, staked a claim, and set about clearing their land of trees and brush so that they could excavate it. Before the prospectors had even started a shaft, Healy crushed his leg in a tree-felling accident. During his recovery, he heard tell of new prospects not far from the Clearwater area and left with Kennedy and another party for the new diggings.

Healy and company had difficulty reaching their new destination due to a series of aggressive yet largely non-violent encounters with Nez Perce Indians strongly opposed to white men trespassing on their hunting grounds. After joining with other similarly-plagued prospecting parties, however, John Healy and his fellow prospectors managed to muscle their way through to their destination. At the new diggings, panning proved fruitless, and the company soon dissolved. Soon, only Healy, Kennedy, and a handful of members of the original company remained. Although these men succeeded in finding better prospects that warranted an excavation, they decided not to exploit their unstaked claim due to lack of game in the area. They travelled to Orofino, a mining boomtown in Clearwater Country, before travelling to a location about 160 kilometers south. There, they staked a claim and purchased provisions before heading back to the site and sinking a shaft. Word of their find got out, and in no time the area was crawling with prospectors. These prospectors founded the boomtown Florence, Idaho, in the vicinity of Healy and company’s find.

Healy and company had difficulty reaching their new destination due to a series of aggressive yet largely non-violent encounters with Nez Perce Indians strongly opposed to white men trespassing on their hunting grounds. After joining with other similarly-plagued prospecting parties, however, John Healy and his fellow prospectors managed to muscle their way through to their destination. At the new diggings, panning proved fruitless, and the company soon dissolved. Soon, only Healy, Kennedy, and a handful of members of the original company remained. Although these men succeeded in finding better prospects that warranted an excavation, they decided not to exploit their unstaked claim due to lack of game in the area. They travelled to Orofino, a mining boomtown in Clearwater Country, before travelling to a location about 160 kilometers south. There, they staked a claim and purchased provisions before heading back to the site and sinking a shaft. Word of their find got out, and in no time the area was crawling with prospectors. These prospectors founded the boomtown Florence, Idaho, in the vicinity of Healy and company’s find.

In the spring of 1862, Healy took a break from digging in order to follow up on a lead indicating a bonanza a good distance away on the Salmon River. Along with a party of twenty lightly-equipped prospectors, John Healy travelled down the Salmon River. What was initially expected to be a brief, exploratory jaunt quickly devolved into a truly grueling ordeal as Healy and company found themselves battling impassable rapids, severe privation, and hostile Bannock Indians. The party’s most formidable foe, however, was starvation, an obstacle the prospectors would all almost surely have succumbed had they not been rescued by a wagon train of fresh prospectors bound for Florence, Idaho.

Upon being nursed back to health, Healy, along with Kennedy and a handful of companions, joined another wagon train bound for Montana Territory. The prospectors took part in another gold rush and saw the beginnings of the burgeoning boomtown of Bannack. When their prospecting efforts were unsuccessful, Healy and company travelled northeast to the fur trading frontier town of Fort Benton, Montana, on the banks of the Missouri River. There, Healy, Kennedy, and a number of fellow prospectors, eager to visit their families back east, boarded a steamer and headed down the Missouri.

Upon being nursed back to health, Healy, along with Kennedy and a handful of companions, joined another wagon train bound for Montana Territory. The prospectors took part in another gold rush and saw the beginnings of the burgeoning boomtown of Bannack. When their prospecting efforts were unsuccessful, Healy and company travelled northeast to the fur trading frontier town of Fort Benton, Montana, on the banks of the Missouri River. There, Healy, Kennedy, and a number of fellow prospectors, eager to visit their families back east, boarded a steamer and headed down the Missouri.

Near the confluence of the Missouri and Milk Rivers, the steamboat happened upon a band of friendly Gros Ventre Indians. No sooner had the steamboat arrived at that location, however, when both it and the Gros Ventre band were surrounded by a large raiding party of Sioux. Although the Sioux and Gros Ventures engaged in a number of skirmishes over the next few days, the mounted Sioux made no move to attack the steamboat passengers.

During this siege, Healy and Kennedy, along with a seasoned Metis trapper named Louis Dauphin, sneaked into the Sioux camp under the cover of darkness and stole a horse without incident. The three men gifted the animal to the Gros Ventures. Shortly thereafter, the Sioux retreated onto the prairies, and the steamboat continued on its way.

22-year-old John Healy returned to New York in the fall of 1862, whereupon he married 18-year-old Mary Frances Sarsfield, the daughter of a well-to-do Irish weaver. In order to avoid the Civil War and conscription in the Union Army, John Healy and his brothers Joseph and Thomas headed for Fort Benton, Montana, in the spring of 1863, leaving the newlywed Mary Frances behind in New York.

The Healy brothers travelled to Montana Territory by way of the Missouri River. In the middle of the prairies, the steamboat they rode became grounded in shallow water and had to be winched along from the shore. During this slow and painful process, the steamboat was set upon by a war party of Sioux braves. A number of passengers- including hopeful prospector and future Montana Indian agent George Steell, American Fur Company baron Charles Chouteau, an Indian scout named “Little Dick”, and Scots-Blackfoot frontiersman Jerry Potts– mounted a successful counterattack that drove the Sioux back, and the steamboat was up and running again in no time.

Upon reaching Fort Benton, Healy set out for the North Saskatchewan River, where a minor gold rush was underway. He scouted the area out before returning to Fort Benton with a Blackfoot half-breed scout named Piscan (or “Buffalo Jump”) Monroe. On the way, the two men were captured and released by a Kootenay raiding party, and later joined a friendlier band of Kootenay Indians who accompanied them all the way to Fort Benton. John Healy, who was raised in the Roman Catholic faith, was greatly impressed when the missionary-influenced Kootenay, despite an obvious food shortage, refused to hunt on the Sabbath.

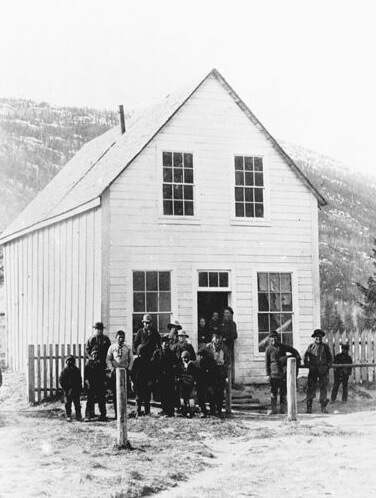

Upon arriving in Fort Benton, Healy gathered together a prospecting party and sent them north to the North Saskatchewan River while he returned east- where his wife and newborn daughter Maria were waiting- for particular supplies. After some fruitless panning and conflict with the Hudson’s Bay Company employees of the nearby Fort Edmonton, the American prospecting party headed back to Montana. William Gladstone, a young carpenter from Montreal from nearby St. Albert, accompanied the Montanans on their return journey.

When Healy returned west with supplies in the summer of 1864 and learned of his men’s conflict with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he made it his life’s mission to “make [the HBC] abandon [Fort Edmonton].” Instead of taking up that mission right away, however, Healy and his prospecting companions made another foray into British possessions, joining a prospecting party fresh from the Wild Horse Creek goldfields (near present-day Fort Steele)- consisting of Sam Livingston (a prominent prospector sometimes dubbed “Calgary’s First Citizen”), James Gibbons, Cass ‘Big Tex’ Huff, Charlie Thomas, and Joe Kipp- who crossed the Rockies by way of the Kicking Horse Pass and were bound for the supposed goldfields of the North Saskatchewan river. After some unsuccessful prospecting, all but Livingston and Gibbons returned south to Montana.

Upon returning to Montana, Healy made the journey east to Virginia City, Nevada, where another gold rush was underway. At the same time, John Healy’s brother Joseph travelled east to New York, where he picked up his brother’s pregnant wife Mary Frances and 1-year-old daughter Maria and brought them with him to Fort Benton. Mary Frances was hailed as “the first white woman in Fort Benton.” When she finally gave birth, her newborn daughter Sarah was the first white baby born in Fort Benton. Unfortunately, Sarah died only nineteen days after being born. When Mary Frances recovered from the tragedy, she and Maria travelled southwest by stagecoach to join John Healy in Virginia City.

After some unsuccessful prospecting in Nevada, the Healy family travelled to Sun River, Montana, where John Healy made a living for some time as a farmer, trader, ferry operator, and Indian Affairs Department agent. During the ensuing years, Healy and his family lived in relative peace in spite of the American Civil War which raged in the east and the bloody Blackfoot Wars, a series of skirmishes and revenge killings between local South Peigan Blackfoot and white Montanan settlers. During this time, John Healy was appointed the commanding officer of the Sun River Rangers, a Montanan vigilante force formed for the purpose of defense against hostile South Peigan.

One night in the spring of 1869, a large band of friendly Blood Blackfoot camped near John Healy’s Sun River trading post was attacked by a large raiding party of Pend d’Oreille Indians. Healy’s post was caught in the crossfire, and the Irishman and his employees engaged with the raiders in a deadly shootout. After the incident, Healy tracked down the fleeing raiding party and, through tact and bravado, managed to both retrieve the herd of horses the Indians had stolen from his coral and make peace with the Pend d’Oreille.

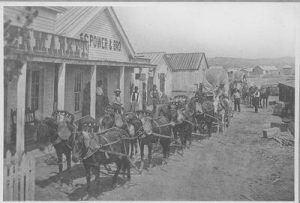

During the Blackfoot Wars of the 1860’s, white settlers and the U.S. Army gradually drove the Blood and South Peigan Blackfoot- Healy’s primary customers- north into the Dominion of Canada’s North-West Territories. In time, John Healy decided to follow his patrons. In the winter of 1869, John Healy partnered up with fellow trader and former prospector Alfred Baker Hamilton, formed the Saskatchewan Mining, Prospecting, & Trading Outfit, secured $25,000-worth of trading stock on credit from Fort Benton wholesaler Tom Powers, and started north for what is now Alberta with a crew comprised of he and Hamilton, frontiersman Jerry Potts, and a handful of others. The crew, after successfully smuggling their goods into British possessions and receiving permission from local Blood chief Buffalo Back Fat, built a trading post on the banks of the Belly (now Oldman) River near present-day Lethbridge, Alberta (a popular winter camp area for the Bloods). This post, formally dubbed ‘Fort Hamilton’ after co-founder Alfred Hamilton, would come to be known colloquially as Fort Whoop-Up.

That winter of 1896/97, Healy, Hamilton, and their employees made more than $50,000 (a small fortune in those days) at Fort Whoop-Up selling goods to the local Blood Indians in exchange for valuable buffalo robes. Although the Montanans sold a number of conventional trading items- including repeating rifles and ammunition, woolen blankets, various metal tools and utensils, flour, sugar, and tea- to the Blackfoot, they also purveyed another commodity which would, in time, cause the Indians considerable grief: whisky.

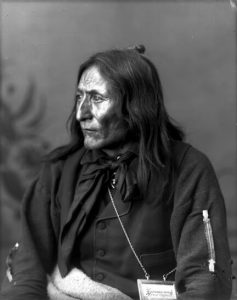

The whisky sold at Fort Whoop-up was a boiled-down rotgut concoction termed ‘firewater’, or ‘bug juice,’ which consisted of American whisky, river water, tobacco plugs, blackstrap molasses, red pepper, red ink, lye soap, Jamaica Ginger, and a dash of strychnine. This beverage was irresistible to the local Blackfoot, who would “undergo every hardship and fatigue to procure a [cupful of it].” Its widespread usage among the Indians had disastrous consequences. Many Blackfoot, under its influence, would murder friends and family in drunken arguments or wander alone out into the prairie and freeze to death, while others would succumb to the toxic beverage itself. Said Siksika Blackfoot chief Crowfoot on the effect of this beverage on his compatriots:

“The whiskey brought among us by the Traders is fast killing us off and we are powerless before the evil. [We are] totally unable to resist the temptation to drink when brought in contact with the white man’s water. We are also unable to pitch anywhere that the Trader cannot follow us. Our horses, Buffalo robes and other articles of trade go for whisky; a large number of our people have killed one another and perished in various ways under the influence.”

After a profitable season on British territory, John Healy, Alfred Hamilton, and a number of Montanan companions returned across the 49th parallel, traded in their season’s take of buffalo robes at Fort Benton, and returned to Fort Whoop-Up the following year. This time, they brought with them carpenter William Gladstone, who built a formidable palisaded fort a short distance from the original post designed to withstand potential Indian raids. Other enterprising Montanan traders, including Joe Kipp and Charlie Thomas, followed their advice and similarly established trading posts on the Belly River.

John Healy would continue to trade whisky and other goods to the Blackfoot in exchange for buffalo robes at Fort Whoop-Up until 1874. During this time, he helped broker a peace between the South Peigan and Pend d’Oreille, witnessed the Battle of Belly River (the world’s last great inter-tribal Indian battle; fought between the Blackfoot and Iron Confederacies), and single-handedly stood off an angry militia of wolfers who styled themselves the Spitzee Cavalry at Fort Kipp (another whisky fort on the Belly River). He also made good on his earlier vow to get back at the Hudson’s Bay Company by buying huge quantities of pemmican from the Blackfoot and Crow Indians, effectively starving Fort Edmonton into dissolution. When the North West Mounted Police formed up and marched west in 1874 with the aim of suppressing the whisky trade that Healy and his Montanan counterparts had brought to Canada, Healy returned south to Montana and spent the summer at Fort Benton. John Healy rode north to Canada the following year, his whisky-peddling past behind him, and acquainted himself with the newly-arrived Mounties.

In the following years, John Healy divided his time between Fort Benton, where he established a grain mill, and Whoop-Up Country, where he continued to trade various goods (aside from whisky) with the Blackfoot and North West Mounted Police. In 1877, he left Canada for good and took up permanent residence at Fort Benton with his family (which, in time, included six children), whereupon the town residents elected him as sheriff of Montana’s Chouteau County. That spring, he was tasked with guarding frontiersman Kootenai Brown, a fellow Irishman who had murdered wolfer Louis Ell in the heat of a dispute over wolf pelts. Several months later, he worked as a scout and interpreter for a volunteer United States militia during the Nez Perce War. In October of that year, John Healy served as an interpreter and consultant for U.S. Army General Alfred Terry during his meeting with Hunkpapa Sioux chief Sitting Bull, who had fled north with his people into Canada following the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Throughout his tenure as sheriff of Chouteau County, John Healy- Irish to the core- exhibited contempt for his British-esque, red-coated counterparts north of the border who had displaced him and his whisky-trading lot in 1874. In 1879, when the North West Mounted Police implored him to extradite a young Blood warrior suspected of murdering the 19-year-old Mountie Constable Graburn who, following the murder, had apparently fled south to Montana, John Healy haughtily offered to do so for $5,000. The Mounties declined the outrageous offer and later captured the Blood fugitive when he returned to Canada to visit relatives.

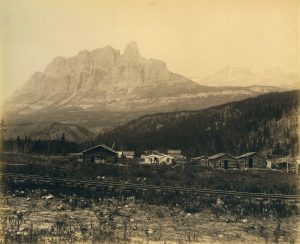

In the early 1880’s, John Healy traded his sheriff’s badge for pick and shovel and once again took up prospecting, this time in the Canadian Rockies west of Calgary. After his brother Joseph discovered copper and silver in promising quantities in the Bow River Valley, John and Joseph Healy, and a number of Canadian and Montanan investors founded Silver City, a boomtown on the Bow River across from Castle Mountain in what is now Banff National Park. Prospectors who flocked to the area soon learned that the area’s precious minerals were in short supply, and Silver City soon devolved into a ghost town.

By that time, the days of the Canadian Wild West were numbered. The bison that had dominated the plains since time immemorial had been hunted to near extinction, the last of the indigenous Plains peoples had been corralled into reserves, and the Canadian Pacific Railway was built across the country, opening up the North-West Territories to settlers. Ever the frontiersman, John Healy, following his and his brother’s financial setback at Silver City, returned briefly to Montana before setting out for the last frontier- the Canadian-American north.

In Juneau, Alaska, Healy acquired a loan which he used to establish a fur-trading and outfitting post on the Dyea Inlet at the end of Lynn Canal, at the base of the Chilkoot Pass. There, he traded various goods to the local Tlingit in exchange for furs, and outfitted the handful of prospectors who trickled over the Chilkoot Pass into the interior in search of Yukon gold. That trickle of prospectors grew to a steady stream during the Fortymile Gold Rush of the late 1880’s. During this time, in which Healy made a respectable profit outfitting hopeful gold miners, Healy’s trading post was the site of a deadly duel between rival Tlingit and Tagish packers. Shortly thereafter, after marrying his second wife Isabella “Belle” Boyd (Mary Frances had succumbed to an illness in Montana back in 1883), John Healy and his new bride were made honourary members of the Crow and Eagle Clans, respectively, of the Tlingit First Nation.

In the 1890’s, John Healy moved inland to the boomtown of Fortymile, where he established an outfitting post. The hard-nosed, no-nonsense entrepreneur did not get along well with many of the boomtown residents. In 1893, he took offense to the verdict of a miner’s meeting- the northern frontier equivalent of a courtroom trial- which stipulated that he compensate one of his female employees for a slight, and sought the assistance of his old enemies, the North West Mounted Police. Due in part to Healy’s entreaty, the North West Mounted Police came to the Yukon to establish law and order.

After the arrival of the North West Mounted Police, John Healy expanded his northern empire. In addition to his trading posts at Dyea and Fortymile, he opened another store at the boomtown Circle City, Alaska (located at the edge of the Arctic Circle), and another at the old coastal port town St. Michael, Alaska (located on the Bering Sea at the mouth of the Yukon River). He also purchased a steamboat, which he used to ferry passengers and freight the length of the massive Yukon River. These expansions served him well; in the late 1890’s, the steady stream of northern prospectors which characterized the Fortymile and Circle City gold rushes of the previous decade swelled into a veritable flood during the Klondike Gold Rush of the late 1890’s. John Healy and his family, several members of which had accompanied him north, made a small fortune during these years, using the considerable profit from their various enterprises to purchase interests in mining claims.

In 1900, 60-year-old John Healy travelled to Nome, Alaska, where another gold rush was underway. Instead of panning for gold, as he was wont to do in the past, the seasoned frontiersman contented himself with observing the operations of a younger generation of adventurers and entrepreneurs before co-founding the Yakutat Fishing Company, which quickly evolved into the Central Alaskan Exploration Company.

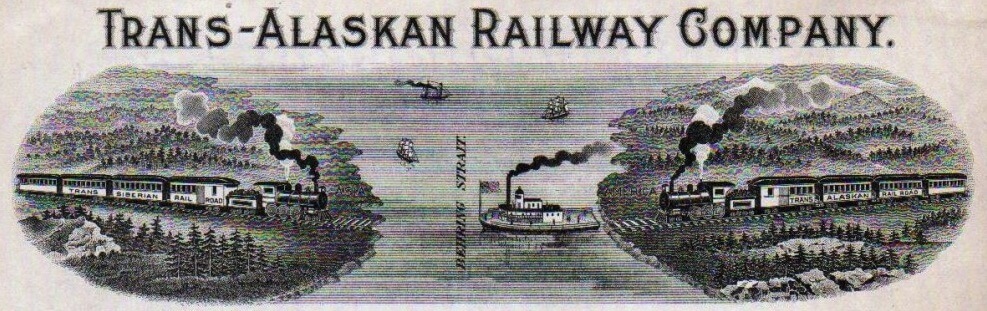

In the early 1900’s, after going through a nasty divorce with Isabella, Healy took on his biggest project yet. Along with a number of international partners, he contrived to construct a railway bridging North America with Siberia by way of the Bering Strait- a hypothetical railway dubbed the Trans-Alaskan Siberian Railroad. John Healy and his North American partners founded the Alaska Northern Railway Company, which would be in charge of the construction of the Alaskan stretch of the trans-continental railroad. After six years of seemingly-successful negotiation with Russian authorities, the venture fell through.

Broke and now in poor health, John Healy retired to San Francisco, where he lived with his daughter Maria and her husband. He became bedridden quite suddenly, and passed away on September 15, 1908, due to liver failure.

Source:

- Healy’s West- The Life and Times of John J. Healy, 2014, Gordon E. Tolton

5 Frontiersmen of the Canadian Wild West:

1) Jerry Potts

4) Joe Kipp

5) Harry “Kamoose” Taylor

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online book store:

Kerry Williams-Freeman

I never knew the history of my Great, Great, Stepfather (Joe Healy’s Stepfather)… till now… thank you!

Hammerson Peters

You’re welcome!

Art

Wow – what a life! Thanks for sharing this. 😀

Hammerson Peters

You’re welcome! Glad you liked it.