This article was originally published on my personal website in 2014.

The Battle of Belly River

If you walk along the shores of the Oldman River in Lethbridge, perhaps on one of the trails in Indian Battle Park, you’ll probably hear the rush of vehicles ripping down Whoop-Up Drive and maybe the occasional train horn. In spite of the prevailing urban ambiance, in that more wild part of Lethbridge it’s not too difficult to imagine a time when the only artificial thoroughfare in the area was the wagon-rutted route of the Whoop-Up Trail, when the only white men around were American adventurers, and when the Oldman River was known by both Indian and trader alike as the Belly River. What is arguably more difficult to imagine is that the rushing of cars and the whistle of train horns, on a day more than a hundred and forty years ago, was replaced by the rattle of musketry and the war cries of Indian braves, and that the serene river valley was the site of the Battle of Belly River, the last great inter-tribal Indian battle in the world.

Background

For centuries before the settlement of the Canadian West in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the Canadian prairies were largely inhabited by the members of two great Indian alliances: the Blackfoot Confederacy and the Iron Confederacy. The warlike Blackfoot Confederacy was composed of the northern Blackfoot (Siksika), the Bloods (Kainai), the northern Peigan (Piikani/ Pikuni), the southern Peigan (Blackfeet), and eventually the unrelated Sarcee (Tsuu Tina) and Gros Ventures. United by blood ties and a common language (Blackfoot/Siksika), the Blackfoot Confederacy traditionally controlled a territory that stretched from the Rocky Mountains of Alberta (west) to the Great Sandhills of Saskatchewan (east), and from the North Saskatchewan River of Alberta (north) to the Yellowstone River of Montana (south). The Iron Confederacy, on the other hand, was an alliance of Plains Cree, Assiniboine (Stone Sioux), Salteaux (Plains Ojibwa), Stoney (Nakoda) and occasionally Metis. Heavily involved as middlemen in the fur trade and as suppliers in the pemmican trade, the Iron Confederacy moved west with the Hudson’s Bay Company onto the Canadian plains- and traditional Blackfoot territory- in the early-mid 1700’s. The Iron Confederacy was initially trading partners and military allies of the Blackfoot on whose lands they inadvertently encroached. However, in time, the two Indian alliances became bitter enemies. The nigh-century of mutual antagonism that existed between the Blackfoot and Iron Confederacies- which began in 1790, after the Gros Ventures joined the Blackfoot Confederacy, and ended in 1871, when the chiefs of the two divisions smoked the pipe of peace on the Red Deer River- resulted in not only countless horse raids, skirmishes, small-scale massacres on the Canadian plains, but also a number of significant battles. The last of these battles, the last great inter-tribal Indian battle in the world, took place along the Oldman (formerly the Belly) River in what is now present-day Lethbridge, Alberta. It is known as the Battle of Belly River.

The Battle

The Battle of Belly River took place on October 25, 1870. Earlier in 1869 and 1870, a massive outbreak of smallpox ravaged the Blackfoot tribes, wiping out nearly half their number. According to Dr. George Allan Kennedy, a North West Mounted Police surgeon stationed at Fort Macleod, the epidemic left in its wake entire camps of Blackfoot “dead lodges” (teepees in which the dead were interred) scattered across the Canadian plains. The chiefs of the Iron Confederacy- namely Piapot, Big Bear, Little Mountain and Little Pine- saw this as an excellent opportunity to deal a crippling blow to their foes and subsequently expand their territory into Cypress Hills, and accordingly raised a war party of 600-800 braves in the Red Ochre Hills, on the South Saskatchewan River near Medicine Hat. Among the warriors were Cree, Salteaux and Young Dogs (a Cree-Assiniboine mix) from the Touchwood Hills and Assiniboine from Wood Mountain. The war party- armed, for the most part, with bows and arrows, old Hudson’s Bay Company muskets and hand-to-hand weapons- set out southwest into Blackfoot territory, following the South Saskatchewan River. One night, when they had reached a point about eighteen miles northeast of present-day Lethbridge, head chief Piapot had a dream that seemed to predict a Cree defeat. In his dream, a buffalo bull with iron horns attacked the Cree warriors. Despite their best efforts, the warriors were unable to kill the beast, and were gored and trampled underfoot. After meditating on his dream, Piapot came to the conclusion that the attack would result in disaster for the Cree. In the morning, he announced his misgivings to the war party, as well as his refusal to participate in the upcoming battle. The more superstitious of the Cree were deeply troubled by Piapot’s vision, and decided to abandon the attack and accompany the aged chief back east, while the more pragmatic of the warriors, recognizing that the Blackfoot had been considerably weakened by smallpox, decided to carry on.

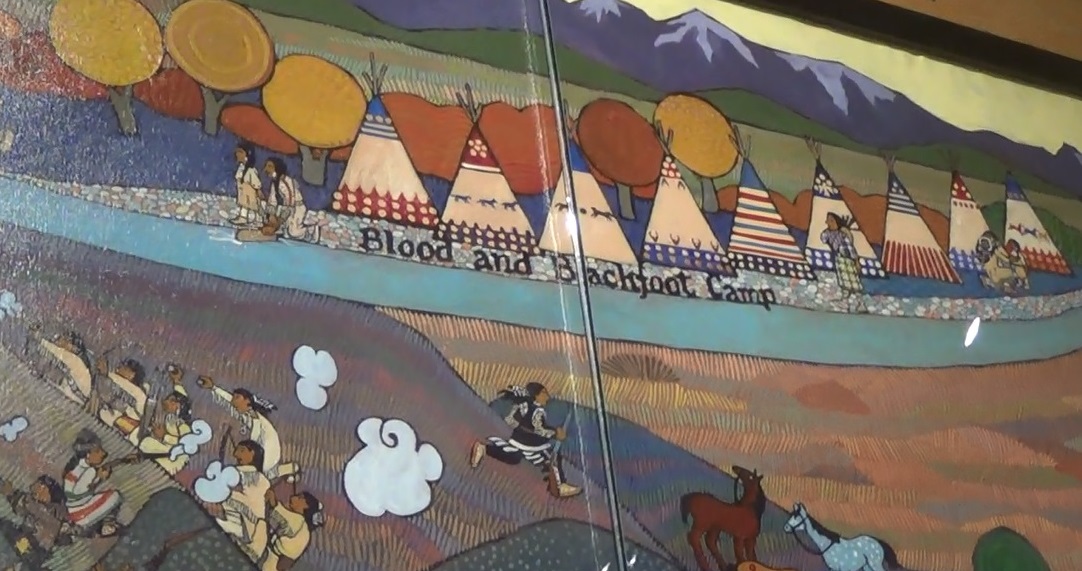

The remaining Cree that resolved to attack the Blackfoot set up camp at the Little Bow River about twenty five miles northeast of Fort Whoop-Up, in the area known as Coyote Flats. Knowing the whiskey fort to be a frequent haunt of the Blackfoot, the Cree sent out scouts to reconnoiter the area. As anticipated, the scouts discovered a Blood camp about three miles north of Fort Whoop-Up, on the Belly River (or several coulees to the south of that, according to Howell Harris, a Fort Whoop-Up whiskey trader who was a spectator of the battle). They stole several horses from the camp and returned to the main party to report their findings. The Cree chiefs, taking the scouts’ information at face value, decided to ambush the camp at night. Unbeknownst to the Cree, the Blood camp they were about to descend on was merely the central part of a much larger winter camp of Blackfoot that extended along the Belly River from Whitney’s Crossing (several miles south of Fort Whoop-Up) all the way to Fort Kipp (about twenty miles northwest of Fort Whoop-Up). In addition to the members of the aforementioned band, many more modestly-equipped Bloods, led by Button Chief and Buffalo Back Fat, were camped in the area. Also camped along the river was a numerically small but well-armed band of Blackfeet (who bore repeating rifles, needle guns and revolvers acquired at whiskey forts) led by Mountain Chief, Big Leg and Black Eagle. This Blackfeet band had been driven north from Montana by a cavalry squadron led by American Army Major Eugene Baker. Smaller bands of north Peigan, led by Crow Eagle, also camped along the river swelled the Blackfoot ranks to a number rivalling that of the Cree. On the eve of October 24, the entire Cree war party set out to ambush Blood camp. According to Francis Red Crow, the grandson of the great Blood chief Red Crow, the Crees, on their way to ambush the Blood camp, happened upon two isolated Blood teepees pitched at the base of Temple Hill (a.k.a. 15 Mile Butte) in what is present-day Raymond. The teepees belonged to two Blood families who were travelling to join a different band of Bloods (part of the same large winter camp) camped along the St. Mary River. Due to exhaustion, the families had decided to camp at the base of the hill rather than complete the journey that night. The Cree killed everyone inside the teepees except for one small boy. After the warriors had left, the boy ended up crawling out of the teepee and making his way to the St. Mary River, where he warned the Bloods of the Cree presence. Sometime that night, the Cree war party arrived at the Blackfoot encampment. A handful of enterprising braves ran into the camp, screaming “We are here!” They slit the teepees of the sleeping Bloods and slaughtered the residents therein. In the foray, the Cree braves killed a brother of Red Crow (a great Blood chief who was absent from the river valley at the time), a number of squaws, and- according to Mountain Horse, the son of Mountain Chief who was in a nearby Blackfeet camp at the time of the attack- several children.

In the midst of the assault, a few Blackfoot women swam across the Belly River towards the main Blood camp in order to call for aid. According to some Blackfoot accounts, one courageous Blood women en-route to the river slayed four Cree braves with only a tomahawk. The efforts of these women, in addition to the sound of gunfire and the barking of the camp dogs, alerted nearby Blackfoot, and by daybreak, the river valley was swarming with warriors.

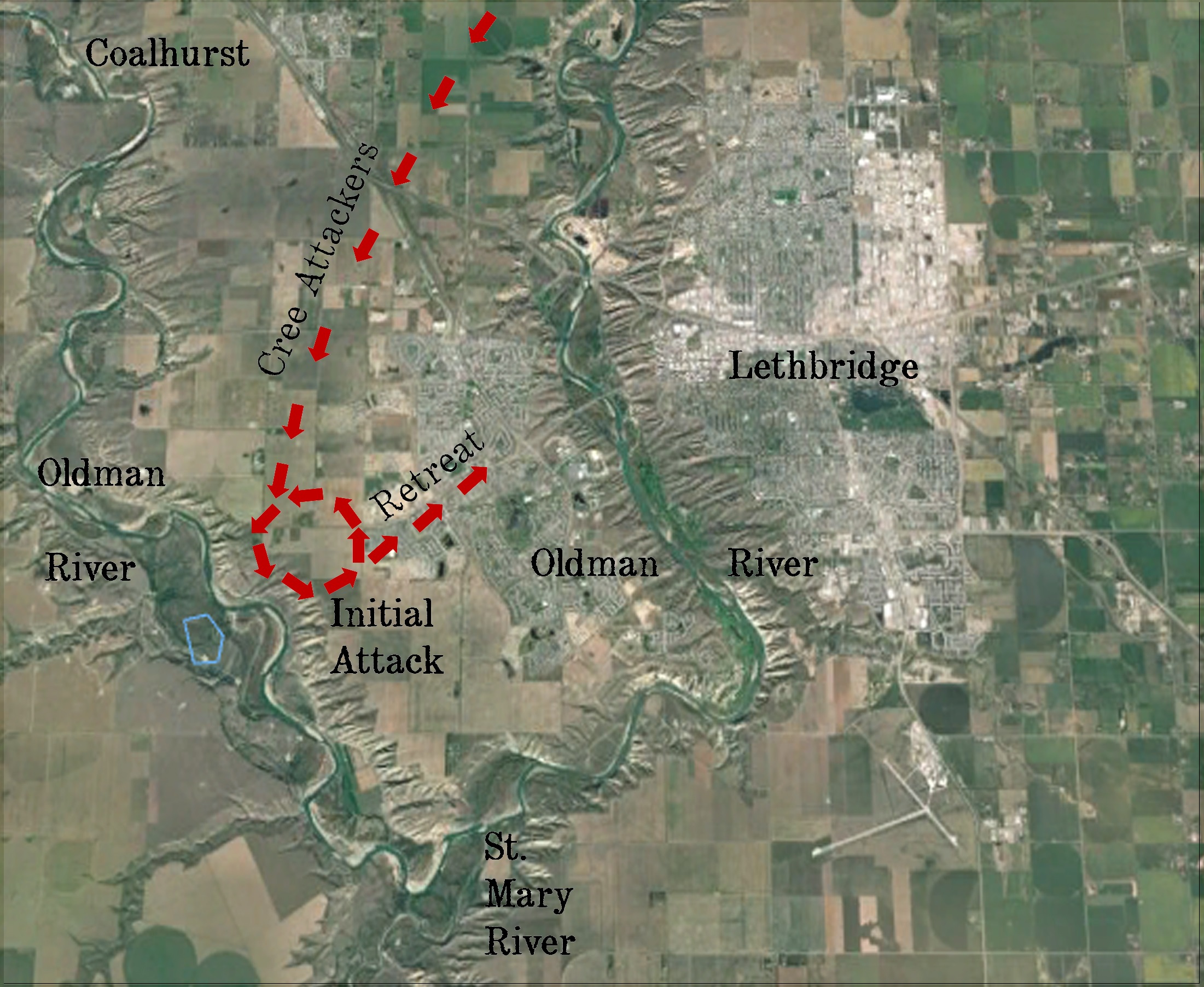

The Cree fought valiantly throughout the night. However, with the arrival of the south Peigan at dawn, they slowly began to retreat across the prairie. When the Cree neared the Belly River, they took up a position in a large coulee that ran from the river up and onto the prairie. The formidable Blackfeet force led by Mountain Chief struggled to secure an opposing position in a short coulee to the south of the Cree while a large number of Bloods, along with a some Blackfeet and north Peigan, simultaneously occupied the prairie to the northwest and a small coulee to the north. The north Peigan and the Bloods were too exposed to engage the Cree, and so fighting commenced between the Cree and the south Peigan.

The Cree and south Peigan occupied two respective coulees that ran parallel to each other for about three hundred to four hundred feet, their ridges separated by a distance that ranged from thirty to two hundred feet. With their horses safely out of range in the valley bottoms, the braves took up positions at the top of the coulees. For four hours they exchanged fire. The warriors, hidden behind their respective coulee crests, would expose themselves just long enough to take aim and pull a trigger or loose an arrow before ducking down again behind the coulee ridge. Some of the warriors who were within throwing range of their enemy hurled stones across the gap. At one point during the battle, two south Peigans mounted their horses and galloped along the ridge in order to estimate the strength and position of the Cree. One of the warriors was shot and killed, while the other had his horse shot from under him and was badly injured. In this engagement, about a dozen Blackfeet were killed, and many more injured. The number of Cree casualties during this firefight is unknown, and up to conjecture; the Cree held a superior position, while the Blackfoot held superior weapons. Throughout the battle, the Blackfeet, north Peigan, and Bloods who occupied the more northerly coulee and prairie worked their way around to the south, where they could better engage the enemy. In time, the barrage from both Blackfoot parties proved to be too much for the Cree, and they gradually, inconspicuously slipped down into the ravine behind them and towards the river.

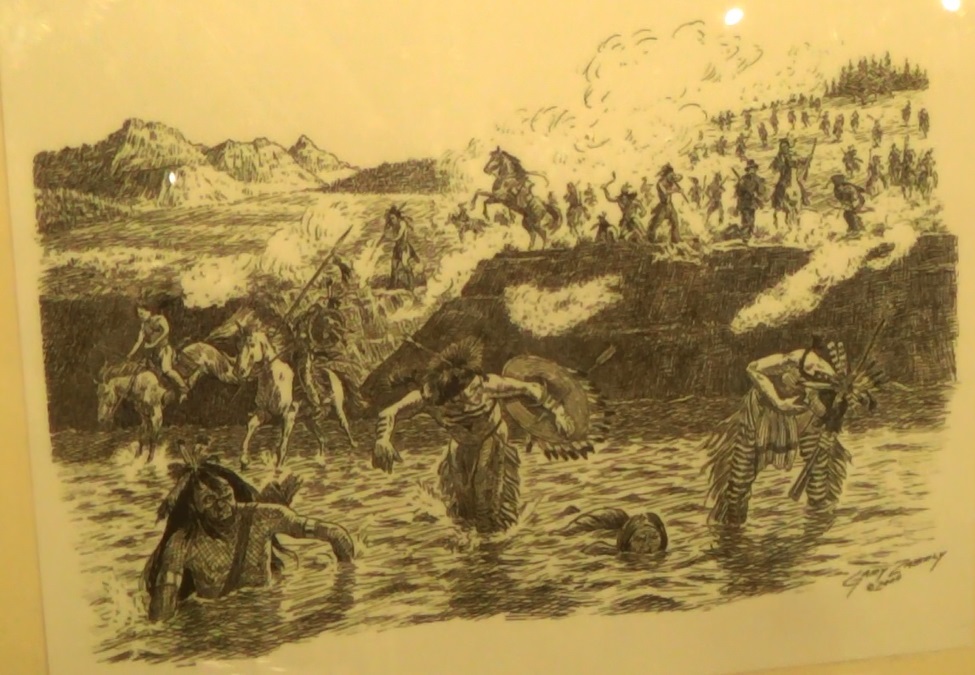

It just so happened that Jerry Potts, the legendary Scots-Peigan scout, was reconnoitering around the bank of the southern ridge at the time of the Cree retreat. Upon discovering the retreat, Potts signalled to the north Peigan to charge. If it weren’t for the actions of Jerry Potts, the battle might have unfolded quite differently. The Peigans did as ordered, and the remaining Blackfeet and Bloods followed suit. In no time, hundreds of Blackfoot warriors, both mounted and on foot, poured over the ridge and into the ravine below. The Cree who were not cut down in the initial onslaught were forced out of the coulee and up a hill to the north. The opposite side of the hill was a steep cutbank of about twenty to thirty feet that ran down to the banks of the Belly River. The Crees, along with their horses, climbed up this hill and tumbled over the other side in a desperate break for the river. The battle that took place thereafter on the western shore of the Belly River at the base of the hill was well-remembered by its participants. A number of eye-witness accounts describe how Calf Shirt (a war chief of the Bloods), with arrows protruding from his neck and arm, killed two Cree champions with a Bowie knife. According to James Sanderson (a respected plainsman), “the Sutherland boys”, two venerated Scots-Cree brothers who fought for the Cree, put up a ferocious last stand on the riverbank. Mountain Horse, a Blackfeet warrior who participated in the battle, recounted his own fierce hand-to-hand combat with Cree braves on the Belly’s shores. In his own words, “Stabbing and drowning was the order of the day.”

Although some Cree chose to fight and die on the riverbank, the vast majority opted to swim across the river. From there, the battle quickly turned into a massacre. The retreating Cree were so closely-packed that they moved almost as a solid mass in the river, and were easy targets for Blackfoot marksmen who fired from atop the cutbanks. In the words of Jerry Potts, “You could fire with your eyes shut and be sure to kill a Cree”. In no time, the air was thick with gun smoke, and the Belly ran red with blood.

There was no respite for the few Cree that managed to reach the east side of the river alive; the Blackfoot were in hot pursuit. Eventually, the Blackfoot overtook their enemy on the open prairie, and remaining Cree made a stand. Around fifty Cree were killed. A handful of survivors fled into a copse of trees to the north, in front of what would later become the Galt mine, and were completely surrounded. Sometime during that final standoff, the Blackfoot decided that enough blood had been spilt. The victors retired to their camps at sunset, allowing the Cree to return home and tell their story.

Aftermath

The Battle of Belly River was one of the bloodiest Indian battles ever recorded in Albertan history. The Blackfoot Confederacy gained a hard-won victory, while the Iron Confederacy suffered a devastating defeat. All told, the Blackfoot had about 90 casualties (40 dead and 50 wounded), while the Cree lost between 200-300 warriors. About a year after the battle, in 1871, the Cree sent tobacco to the Blackfoot as a peace offering, and in the fall of that year, the chiefs of the two rival nations met on the shores of the Red Deer River to make a formal treaty of peace. Although the Blackfoot and Cree, in spite of this formal peace, continued to engage in minor skirmishes for the next sixteen years, the Battle of Belly River remained the last major battle between them, and indeed was the last great inter-tribal Indian battle in the world.

Source

- The Last Great (Inter-Tribal) Indian Battle, Dr. Alexander Johnston and the Lethbridge Historical Society, 1997.

Josephine Staddon

A very interesting and exciting article. Please check your geography as journeying south east from Medicine Hat area does not bring you north of Lethbridge. You need to travel west o MH. Also for the sake of propriety