The following is an article which I originally published on my personal website in 2014.

How Medicine Hat Got Its Name

“Medicine Hat? What a weird name!”

This remark, or some variation thereof, is usually one of the first things I hear after I mention ‘Medicine Hat’ to somebody who’s never heard of it before.

If you happen to be learning about Medicine Hat for the first time, please allow me to fill you in. Medicine Hat- or “the Hat”, as the locals call it- is a prairie city in southeast Alberta, Canada, that currently boasts around 60 000 residents. It lies on the South Saskatchewan River and on the Trans-Canada Highway about 50 km west of the Saskatchewan border, and was founded in 1883, when the Canadian Pacific Railway was built across the river.

If you happen to be learning about Medicine Hat for the first time, please allow me to fill you in. Medicine Hat- or “the Hat”, as the locals call it- is a prairie city in southeast Alberta, Canada, that currently boasts around 60 000 residents. It lies on the South Saskatchewan River and on the Trans-Canada Highway about 50 km west of the Saskatchewan border, and was founded in 1883, when the Canadian Pacific Railway was built across the river.

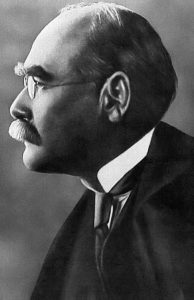

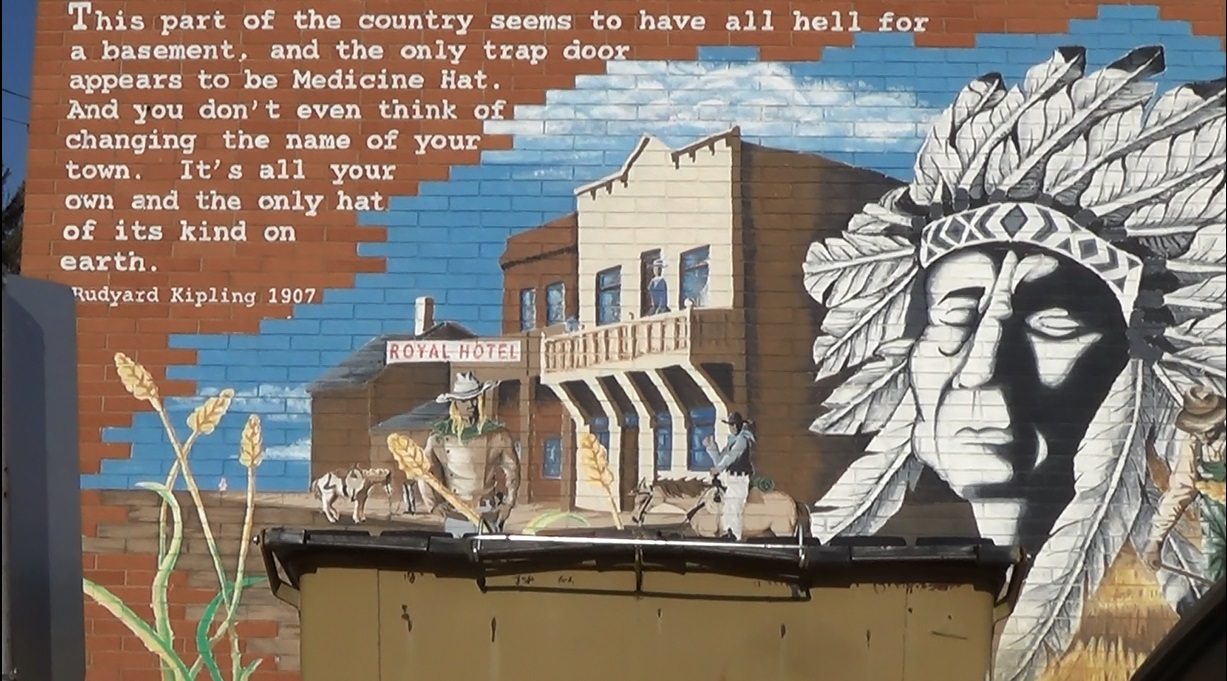

Although Medicine Hat has spent time in the Canadian spotlight for a number of different reasons, perhaps its true and most timeless claim to fame is its strange name. As is the case with most things that deviate from the norm, Medicine Hat’s name wasn’t always unanimously accepted. In fact, some early Hatters- as Medicine Hat residents are sometimes called – considered the name to be so bizarre that in 1910, when natural gas was discovered in the area, they petitioned to change it. These disgruntled citizens believed that industries might be attracted to a city with a more conventional name like Gasburg (which would reflect the city’s newfound natural gas) or Smithville (in honour of the C.P.R. co-founder Sir Donald Smith (a.k.a. Lord Strathcona)). A number of old-school Hatters, however, strongly opposed this proposal and entreated the support of Rudyard Kipling, the famous English writer who had a special place in his heart for Medicine Hat. Kipling responded by advocating the old name in a letter written to Francis F. Fatt, the editor of the Medicine Hat News. In this letter, Kipling wrote:

Although Medicine Hat has spent time in the Canadian spotlight for a number of different reasons, perhaps its true and most timeless claim to fame is its strange name. As is the case with most things that deviate from the norm, Medicine Hat’s name wasn’t always unanimously accepted. In fact, some early Hatters- as Medicine Hat residents are sometimes called – considered the name to be so bizarre that in 1910, when natural gas was discovered in the area, they petitioned to change it. These disgruntled citizens believed that industries might be attracted to a city with a more conventional name like Gasburg (which would reflect the city’s newfound natural gas) or Smithville (in honour of the C.P.R. co-founder Sir Donald Smith (a.k.a. Lord Strathcona)). A number of old-school Hatters, however, strongly opposed this proposal and entreated the support of Rudyard Kipling, the famous English writer who had a special place in his heart for Medicine Hat. Kipling responded by advocating the old name in a letter written to Francis F. Fatt, the editor of the Medicine Hat News. In this letter, Kipling wrote:

“…To my mind, the name of Medicine Hat has an advantage over (other cities with similarly unique names). It echoes as you so justly put it the old Cree and Blackfoot tradition of red mystery and romance that once filled the prairie… Believe me, the very name is an asset, and as years go on will become more and more of an asset. It has no duplicate in the world; it makes men ask questions, and as I knew, more than twenty years ago, draws the feet of the young men towards it; it has the qualities of uniqueness, individuality, assertion and power.

Above all, it is the lawful, original, sweat-and-dust-won name of the city and to change it would be to risk the luck of the city to disgust and dishearten old-timers, not in the city alone, but the world over…

… (A man’s city) is the living background of his life and love and toil and hope and sorrow and joy. Her success is his success; her shame is his shame’ her honour is his honour; and her good name is his good name.”

Kipling concluded with, “What then should a city be rechristened that has sold its name? Judasville.”

Perhaps due in part to Kipling’s letter (which was printed on the front page of the Medicine Hat News), the town decided, in a ten-to-one vote, to keep the old name, which it bears to this day.

So how did Medicine Hat come by such a provocative and controversial name? As it turns out, there is no clear answer. On the contrary, there are a number of different (and conflicting) explanations for how Medicine Hat came to be called what it is. Most of these explanations claim that the name ‘Medicine Hat’ is based on either:

1) A battle between the Blackfoot and Cree;

2) A native legend involving love and human sacrifice;

3) A landmark that looks like an Indian’s headdress.

In spite of their differences, every single explanation has something in common, namely the inclusion of a medicine man’s headdress, or a ‘medicine hat’ (saamis, in Blackfoot (Siksika)). Below are the 17 most common explanations for how Medicine Hat got its name.

Battle Legends

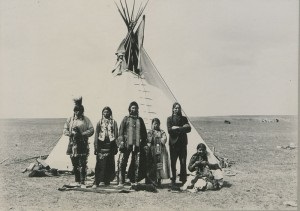

A number of different Indian legends claim that Medicine Hat received its name from an incident that occurred during a battle between the Blackfoot and the Cree. Some of these legends are described below.

Legend 1: The Battle of Bitter Lake

Background

The earliest recorded battle legend about Medicine Hat’s naming was published in Regina’s, Leader Post, on July 5, 1883. This story places the battle on the shores of ‘Bitter Lake’, the Indian name for some mysterious body of water. It is interesting to note that there is a ‘Bitter Lake’ that lies less than 60 km east of Medicine Hat, just across the Saskatchewan border slightly east of Many Island Lake.

The Legend

Many years ago, the Blackfoot and the Iron Confederacy (Cree and Assiniboine Sioux) fought a battle on the shores of “what is known among the Indians as ‘Bitter Lake’”. During the heat of battle, the Assiniboine medicine man lost his hat. After the battle was over (a Blackfoot victory), the medicine man and a handful of braves returned to the battlefield to search for the lost hat. Although they searched until sunset, they found no sign of the hat. At dusk, just as the warriors were preparing to abandon their search, an enormous, shadowy figure emerged in the middle of Bitter Lake. The figure, which appeared to be a man standing on the water’s surface, held the medicine man’s hat in his outstretched hand. The warriors watched in horror as the figure, along with their medicine man’s beloved hat, disappeared beneath the waves.

Legend 2: The Medicine Man’s Vision

Background

Many prairie frontiersmen affirmed that Medicine Hat was so named because of the vision of a medicine man. Their early accounts are summarized in an article that appeared on the front page of the Medicine Hat Times on November 12, 1885.

Legend

Sometime in the early 1860’s, a band of Blackfoot was camped by the cliffs near present day Police Point Park. One morning, the Blackfoot were surprised to discover that a party of Cree was camped close by. In order to prepare the band’s warriors for the battle that would inevitably take place, the Blackfoot shaman began to prepare some powerful medicine. As he worked, he saw the image of a medicine hat reflected in the water of the South Saskatchewan River. When he had finished preparing the medicine, the shaman told the braves of his vision and assured them that it was a good omen. The Blackfoot warriors rode out with the newly-made medicine and the encouraging words of the medicine man still ringing in their ears. They confronted the Cree, engaged them in battle and were utterly victorious. From that point on, the place was known as Medicine Hat.

Sometime in the early 1860’s, a band of Blackfoot was camped by the cliffs near present day Police Point Park. One morning, the Blackfoot were surprised to discover that a party of Cree was camped close by. In order to prepare the band’s warriors for the battle that would inevitably take place, the Blackfoot shaman began to prepare some powerful medicine. As he worked, he saw the image of a medicine hat reflected in the water of the South Saskatchewan River. When he had finished preparing the medicine, the shaman told the braves of his vision and assured them that it was a good omen. The Blackfoot warriors rode out with the newly-made medicine and the encouraging words of the medicine man still ringing in their ears. They confronted the Cree, engaged them in battle and were utterly victorious. From that point on, the place was known as Medicine Hat.

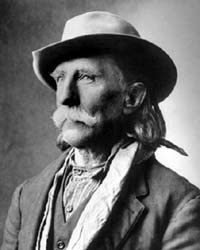

Legend 3: Kootenai Brown’s Legend

Background

One of the battle legends was recorded in 1898 by Charles M. Skinner, the famous American writer, folklorist and editor of New York’s Brooklyn Eagle. This particular version of the battle legend, which was published in Skinner’s Myths and Legends Beyond Our Borders, also recurs in the respective writings of Canadian frontier legend John George “Kootenai” Brown (Reminiscence of Western Canadian Travels, 1865-1900) and Rev. Dr. W. Everard Edmonds, a Canadian history professor (Broad Horizons, 1919).

One of the battle legends was recorded in 1898 by Charles M. Skinner, the famous American writer, folklorist and editor of New York’s Brooklyn Eagle. This particular version of the battle legend, which was published in Skinner’s Myths and Legends Beyond Our Borders, also recurs in the respective writings of Canadian frontier legend John George “Kootenai” Brown (Reminiscence of Western Canadian Travels, 1865-1900) and Rev. Dr. W. Everard Edmonds, a Canadian history professor (Broad Horizons, 1919).

Legend

There was once a successful Blackfoot chief who attributed all his good fortune to the eagle feather headdress that he wore. One day, he and his warriors bore down upon a war party of Cree at a place that is near present-day Medicine Hat. Initially, the Blackfoot were wildly successful, led as they were by their courageous, headdress-wearing chief. However, just as it seemed the Blackfoot would rout the Cree, a gust of wind whirled the headdress off the chief’s head and into the South Saskatchewan River. Dismayed, the Blackfoot chief called off the attack and retreated, certain that he would be unable to secure a victory without his lucky hat. He retired to the Cypress Hills, and died broken-hearted shortly thereafter. From that point on, the Blackfoot referred to the site of the battle as “Saamis”, or ‘Medicine Hat’.

There was once a successful Blackfoot chief who attributed all his good fortune to the eagle feather headdress that he wore. One day, he and his warriors bore down upon a war party of Cree at a place that is near present-day Medicine Hat. Initially, the Blackfoot were wildly successful, led as they were by their courageous, headdress-wearing chief. However, just as it seemed the Blackfoot would rout the Cree, a gust of wind whirled the headdress off the chief’s head and into the South Saskatchewan River. Dismayed, the Blackfoot chief called off the attack and retreated, certain that he would be unable to secure a victory without his lucky hat. He retired to the Cypress Hills, and died broken-hearted shortly thereafter. From that point on, the Blackfoot referred to the site of the battle as “Saamis”, or ‘Medicine Hat’.

Legend 4: The Cree Battle Legend

Background

Another version of the battle legend, which can perhaps be most accurately described as the Cree version, was recorded by Earl Joseph Gillett, a retired CPR engineer and amateur historian, from 1923-1948. In writing this version of the legend, which he maintained was the authentic version, Gillett gathered information from five different sources: 1) J.H.G. Bray, a Sergeant Major in the North West Mounted Police who was posted first at Fort Macleod and later at Fort Walsh following his enlistment in Toronto in 1873; 2) Sergeant Robert McCutcheon, a NWMP officer who, after enlisting in 1875, served for years in the Cypress Hills before becoming one of Medicine Hat’s first white residents; 3) Michael Quesnelle, an accomplished NWMP Scout who also enlisted in 1875; 4) Litto Cohn (a.k.a. Little Corn), a Cree authority on local folklore; 5) Sun Child, another Cree man familiar with Cree legend.

Another version of the battle legend, which can perhaps be most accurately described as the Cree version, was recorded by Earl Joseph Gillett, a retired CPR engineer and amateur historian, from 1923-1948. In writing this version of the legend, which he maintained was the authentic version, Gillett gathered information from five different sources: 1) J.H.G. Bray, a Sergeant Major in the North West Mounted Police who was posted first at Fort Macleod and later at Fort Walsh following his enlistment in Toronto in 1873; 2) Sergeant Robert McCutcheon, a NWMP officer who, after enlisting in 1875, served for years in the Cypress Hills before becoming one of Medicine Hat’s first white residents; 3) Michael Quesnelle, an accomplished NWMP Scout who also enlisted in 1875; 4) Litto Cohn (a.k.a. Little Corn), a Cree authority on local folklore; 5) Sun Child, another Cree man familiar with Cree legend.

The Legend

One day in 1870, a party of Cree crossed the South Saskatchewan River from the southeast, at the shallow part of the river that is in between present day Police Point Park and Strathcona Island Park (at the mouth of Ross Creek). After exploring the cottonwood thicket of Police Point, the Cree made their way upriver (west) and discovered the natural spring on the hillside of present day Hargrave Park (on Division Avenue and 4 Street NE).

One day in 1870, a party of Cree crossed the South Saskatchewan River from the southeast, at the shallow part of the river that is in between present day Police Point Park and Strathcona Island Park (at the mouth of Ross Creek). After exploring the cottonwood thicket of Police Point, the Cree made their way upriver (west) and discovered the natural spring on the hillside of present day Hargrave Park (on Division Avenue and 4 Street NE).

The Cree, who drank from the spring, were unaware that they were being watched by a war party of Blackfoot. The Blackfoot warriors, who had been spying on the Cree from atop present-day Crescent Heights, waited until their enemies had quenched their thirst before screaming their war whoops and charging down the hill towards them. Frantically, the Cree leapt onto their horses and thundered east towards the ford they had just crossed.

When the Cree crossed the ford and reached the northern shore of Strathcona Island, they stood their ground and showered upon their pursuers a volley of arrows. The Blackfoot medicine man, who rode at the head of the warriors, was shot in the heart by one of the first arrows. In his death throes, the medicine man reared up on his stallion, and as he did so his feathered war bonnet was blown off by the wind. The medicine man’s hat fell into the river and floated against the shores of Strathcona Island.

The remaining Blackfoot warriors watched in horror as their medicine man’s headdress was picked up by the Cree. Imagining that the Great Spirit had forsaken them, they fled back across the river to Police Point.

Later, the Blackfoot returned to the spot and built a stone cairn on the north shore of the river, on the banks of present-day Police Point, in remembrance of the event. Although the cairn has since been scattered into oblivion by Medicine Hat’s many floods, the Indian name for the location, ‘The Place of the Medicine Hat’, remains to this day.

Legend 5: Reverend Morrow’s Legend

Background

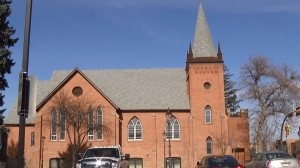

Reverend James William Morrow, a minister of Medicine Hat’s St. John’s Presbyterian Church from 1896-1918, described a different battle ostensibly responsible for the city’s name in his 1923 book, Early History of the Medicine Hat Country. This version, which bears some resemblance to Gillett’s Cree battle version, is echoed almost exactly in Edna Baker’s 1934 book, Prairie Place Names.

Legend

“Many years before the coming of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police” (before 1874), a band of Crees were camped in Medicine Hat’s present day Riverside district, as “good water was very easily obtained from the springs on the hillside”.

Blackfoot scouts spotted the Cree camp and attacked the next morning. Although caught unawares, the Cree managed to rally quickly and put up a fierce fight. In spite of their efforts, however, the Cree were slowly driven east towards Police Point. A number of Cree braves struggled to hold back the Blackfoot just long enough to allow their squaws, ponies and remaining warriors to cross the river into Strathcona Island.

While the Cree medicine man was crossing the river (in Baker’s version, he was fleeing with the women), a gust of wind blew his hat off his head and tossed it into the South Saskatchewan. The Cree warriors that had already crossed the river saw this, and perceived it to be a bad omen. Immediately, they lost all confidence and fled northeast. The victorious Blackfoot pursued the fleeing Cree as far as Many Island Lake. From that point on, the ford at which the incident occurred has been known as “the place-where-the-medicine-man-lost-his-hat”.

Legend 6: The Day the Medicine Man Lost His Hat

Background

Another version of the battle legend, which is arguably the version most frequently affirmed by Hatters and (inarguably) one of the two versions officially espoused by the city, is an old local story which was eventually printed in the Medicine Hat News. Today, this version is printed on postcards entitled, The Day the Medicine Man Lost His Hat, which are freely distributed at Medicine Hat’s City Hall.

The Legend

There was once a great battle between the Blackfoot and Cree that took place on the shores of the South Saskatchewan River (some place the battlefield near present day Finlay Bridge). Although the belligerents were roughly equal in strength, it appeared that the Cree had the upper hand. In the midst of battle, the Cree medicine man, fearing for his life, deserted his kinsmen and swam across the river. In his haste, he lost his headdress midstream to an undercurrent. The Cree braves, upon witnessing the cowardice of their shaman, proclaimed the disappearance of his headdress to be a bad omen and subsequently broke and fled. The Cree warriors, who at first appeared to be winning the battle, were completely routed by the Blackfoot.

Legend 7: The Horner Family Legend

Background

James Henry Horner, one of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s first road masters stationed in Medicine Hat, heard an explanation for Medicine Hat’s name from an old Indian guide. He passed this story down to his son, David Edson Horner, who in turn told it to Marcel M.C. Dirk, a Medicine Hat resident, writer and historian. Dirk recorded this version in his 1993 book But Names Will Never Hurt Me.

This legend is notable in that it involves both a battle between the Blackfoot and Cree and human sacrifice.

The Legend

There was once a battle between the Blackfoot and the Cree along the South Saskatchewan River at the place where the Medicine Hat Arena now stands. The Blackfoot drove the Cree southeast to the area that is between present day Industrial Avenue (to the south), Seven Person’s Creek (to the west) and Ross Creek (to the east), just east of the Medalta Historic Clay District and south of the mouth of Ross Creek. The Cree retreated further, climbing up what is now Porter’s Hill and onto the top of the steep cliffs that overlook the river. There, they were massacred by the Blackfoot. Hundreds of warriors were buried atop these cliffs.

There was once a battle between the Blackfoot and the Cree along the South Saskatchewan River at the place where the Medicine Hat Arena now stands. The Blackfoot drove the Cree southeast to the area that is between present day Industrial Avenue (to the south), Seven Person’s Creek (to the west) and Ross Creek (to the east), just east of the Medalta Historic Clay District and south of the mouth of Ross Creek. The Cree retreated further, climbing up what is now Porter’s Hill and onto the top of the steep cliffs that overlook the river. There, they were massacred by the Blackfoot. Hundreds of warriors were buried atop these cliffs.

Shortly after the battle, a Blackfoot warrior rode down to the river and prayed that he might one day become the most powerful medicine man in his tribe. While he was praying, he came upon a serpent who told him that his prayers would be answered if he gave the serpent the youngest of his three wives.

The warrior sacrificed his youngest wife to the serpent. Appeased, the serpent instructed the warrior to locate and dig under a large cottonwood tree that grew in a deep ravine in which a spring flowed. The warrior found the tree (at a location that is up present day Parkview Drive east of Maple Avenue), dug at its base and found a plumed medicine hat. Aided by the power of the hat, the warrior went on to become the most powerful medicine man of the Blackfoot tribe and came to be known as “The Man of the Medicine Hat”.

Legend 8: The Top Hat Massacre

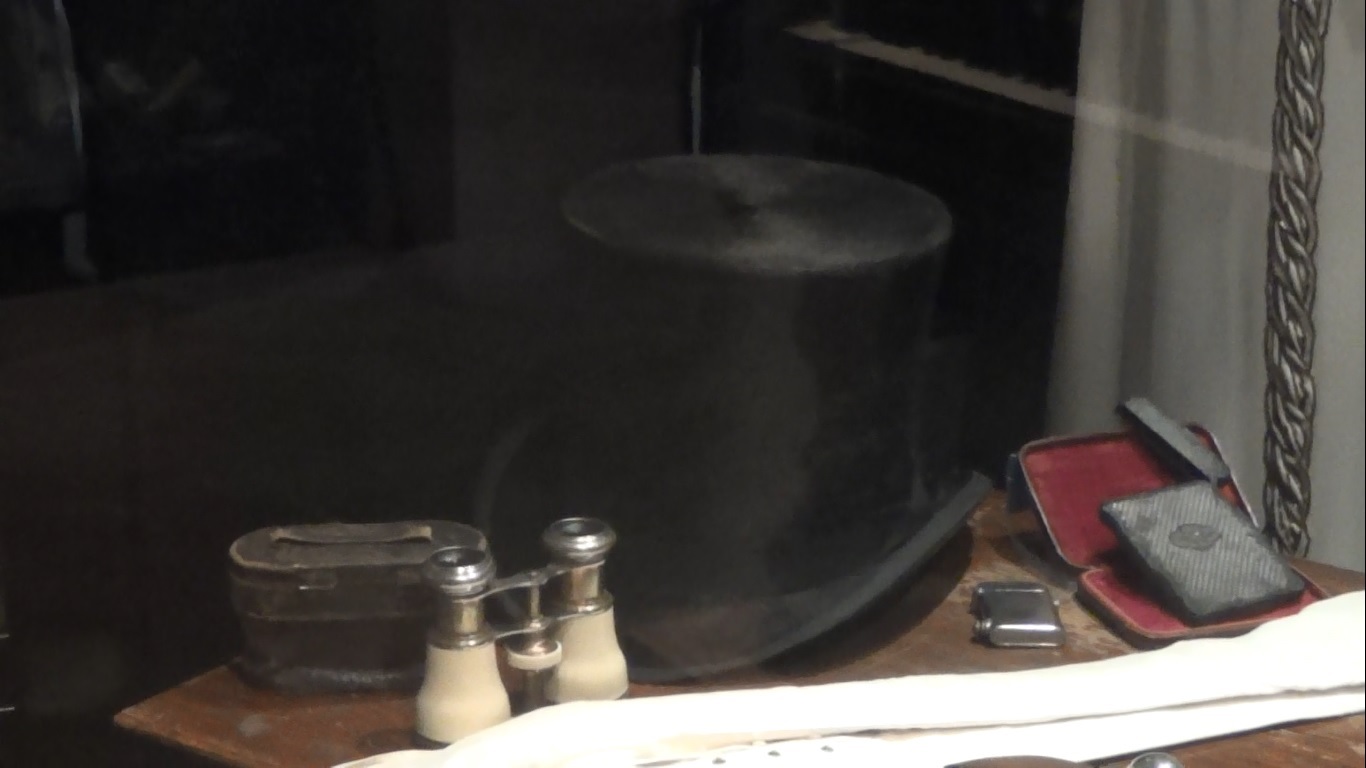

One old story passed down through the years by word of mouth is that, many years ago, an Indian war party massacred a group of white settlers. The Indian medicine man among them scavenged the white corpses and took either a young girl’s frilly bonnet or a man’s beaver felt top hat.

Legends of Love and Human Sacrifice

Legend 9. The Kainai (Blood) Blackfoot Sacrifice Legend

Background

James Francis Sanderson, a half breed frontiersman and businessman, documented a Kainai Blackfoot version of how Medicine Hat got its name in his 1894 book Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies. The same story was retold by Reverend Charles Stephens of St. John’s Presbyterian Church in a Medicine Hat News article, and is now one of the two official explanations for the origin of the city’s name.

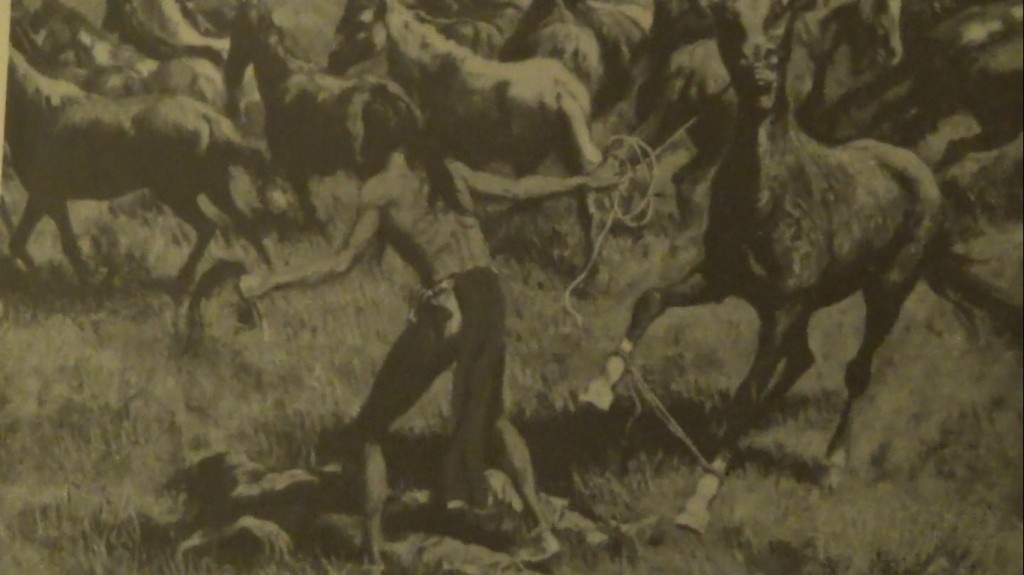

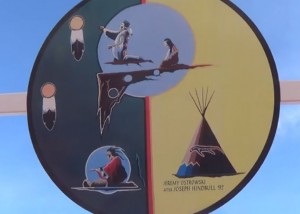

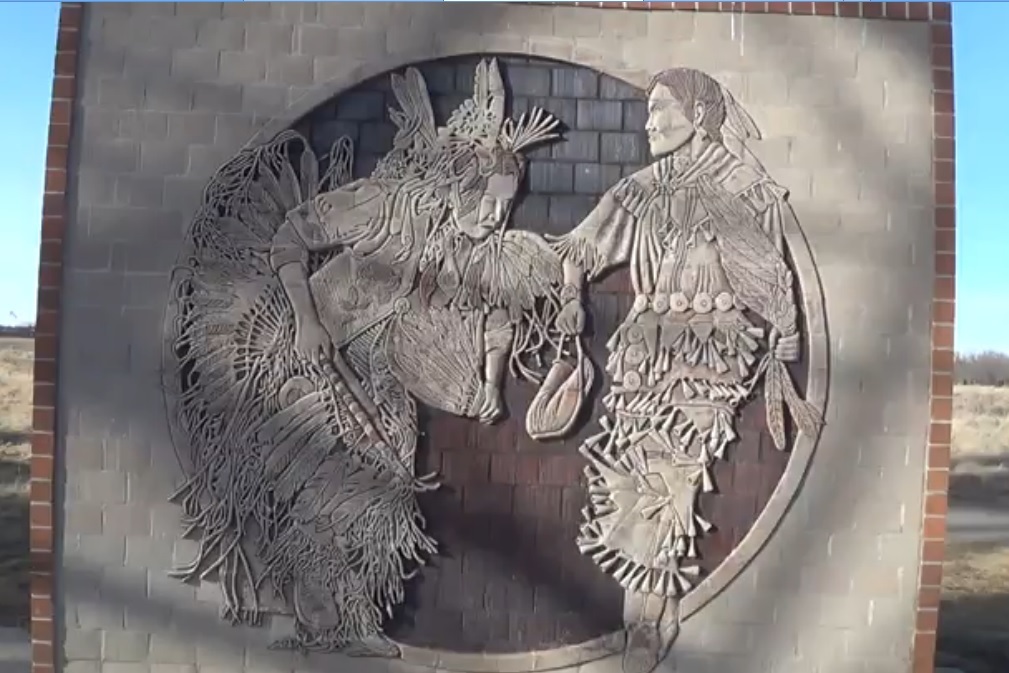

Jim Marshall, a Medicine Hat artist and sculptor, immortalized this Blood legend in an enormous brick mural that graces the foyer to the Council Chambers in Medicine Hat’s City Hall.

The Legend

There is a part of the South Saskatchewan River between Police Point Park and Strathcona Island Park that remains free of ice all year round, even during the most severe winters. The Blackfoot believed that this place was the breathing hole of the Great Spirit.

Far back in Blackfoot tradition, it is told that a young Blood hunter was tasked with scouting for buffalo during a particularly severe winter. The hunter, accompanied by his newly married wife and his favorite dog, journeyed down the frozen South Saskatchewan River. After several days of travelling, the trio arrived at the aforementioned part of the river on which ice never forms and made camp on the riverbank.

That evening, the hunter walked alone alongside the river. As he walked, the Great Spirit, in the form of an enormous serpent, slithered from the water. The serpent told the hunter that he would become great chief and medicine man if he threw the body of his wife into the river.

The hunter returned to his wife and told her what the Great Spirit had said. The wife immediately expressed her willingness to die for her husband and for the good of the tribe. Of course, the hunter was reluctant to sacrifice his wife, and so he sacrificed his favorite dog instead and prayed that its carcass might serve as a substitute. Upon throwing the body of his dog into the river, however, the serpent emerged again and told him that unless his wife was sacrificed, he could do nothing.

Again, the hunter returned to his wife and told her what the serpent had said. Again, his wife selflessly acquiesced. Finally, with great reluctance, the hunter sacrificed his wife and gave her body to the serpent.

Appeased, the serpent instructed the hunter to spend the night on the small island nearby (at the mouth of Ross Creek). In the morning, he would proceed to the cut banks to the east and find a medicine hat at the base of the cliffs. The headdress, the serpent told him, was only to be worn in battle, and would ensure victory to the wearer. Tradition has it that the hunter became a great medicine man and warrior.

Appeased, the serpent instructed the hunter to spend the night on the small island nearby (at the mouth of Ross Creek). In the morning, he would proceed to the cut banks to the east and find a medicine hat at the base of the cliffs. The headdress, the serpent told him, was only to be worn in battle, and would ensure victory to the wearer. Tradition has it that the hunter became a great medicine man and warrior.

Legend 10: Officer Turner’s Legend

Background

In 1905, J.P. Turner, an officer of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Historical Research Department, “made inquiries bearing on the origin of the unusual name (of Medicine Hat)”. Turner heard many versions regarding the subject from old Indians and white pioneers from both Fort Macleod and Medicine Hat, and wrote down the version “that appeared most authentic and vouched for” by his interviewees.

Senator Dr. Fredrick William Gershaw, an early Medicine Hat resident, physician, politician and amateur historian (who is the namesake of Medicine Hat’s Gershaw Drive and Bow Island’s Senator Gershaw School), included Turner’s story (which is remarkably similar to Sanderson’s Blood Version) in his book Saamis: The Medicine Hat.

Legend

There is a small part of the South Saskatchewan River on which no ice ever forms (between Police Point and Strathcona Island). While camped at this part of the river on the southern shore (Strathcona Island), a Blackfoot warrior had a vision. A figure (either an Indian chief or a huge serpent) wearing a magnificent feathered headdress rose from the opening in the ice. Incidentally, the young warrior was engaged to marry love of his life at the time, and was told that if he threw her to the figure, he would become the greatest of all the chiefs. Out of love for her fiancé, the girl agreed to be sacrificed, and was thrown beneath the water. The place has been known as the “spot of the Medicine Hat” ever since.

There is a small part of the South Saskatchewan River on which no ice ever forms (between Police Point and Strathcona Island). While camped at this part of the river on the southern shore (Strathcona Island), a Blackfoot warrior had a vision. A figure (either an Indian chief or a huge serpent) wearing a magnificent feathered headdress rose from the opening in the ice. Incidentally, the young warrior was engaged to marry love of his life at the time, and was told that if he threw her to the figure, he would become the greatest of all the chiefs. Out of love for her fiancé, the girl agreed to be sacrificed, and was thrown beneath the water. The place has been known as the “spot of the Medicine Hat” ever since.

Legend 11: Thunder Bear’s Elopement

Background

W.H. McKay and James Sallows, Cree half breeds and pioneers who contested Gillett’s Cree battle legend, believed that Medicine Hat was named by William Cornelius Van Horne (General Manager and later President of the Canadian Pacific Railway) after listening to the account of a noted Cree chief named Thunder Bear. According to McKay, a middle aged Thunder Bear met with Van Horne at his uncle’s cabin in the spring of 1883 and told him a personal anecdote. Upon hearing the Indian’s tale, Van Horne supposedly decided to name the new village on the South Saskatchewan ‘Medicine Hat’.

This account was documented by Marcel M.C. Dirk, a Hatter historian, in his book But Names Will Never Hurt Me, by Senator Dr. Frederic William Gershaw, a Medicine Hat physician and politician, in his book Saamis: The Medicine Hat, and by Ed Gould, in his book All Hell for a Basement. In Gershaw’s version, the Cree narrator is named chief Thunder Bird (instead of Thunder Bear).

The Legend

In the summer of 1862, chief Red Deer (the Cree chief who is the namesake of Red Deer, Alberta) “was camped with his tribe where the river that bears his name joins the swift flowing water” (near Empress). In one of Red Deer’s teepees lived a beautiful girl named Silver Rose. The old chief, who already had four older wives, had forced the girl to marry him against her will.

Thunder Bear loved Silver Rose, and when he heard that she had married Red Deer against her will, he rode into Red Deer’s camp, rescued her from the chief’s teepee and rode off with her. The couple came to “the place where the river runs (closest to) the Cypress Hills” (present day Medicine Hat), and camped on a small island in the river between present day Police Point and Strathcona Island. They chose to come to this spot, Thunder Bear maintained, since it was “very dangerous territory” and subsequently the last place that the chief would expect to find them. On their fifth day on the island, the water level began to rise, and so they crossed to the south shore (Strathcona Island) and pitched their teepee at the foot of the cliffs.

Thunder Bear loved Silver Rose, and when he heard that she had married Red Deer against her will, he rode into Red Deer’s camp, rescued her from the chief’s teepee and rode off with her. The couple came to “the place where the river runs (closest to) the Cypress Hills” (present day Medicine Hat), and camped on a small island in the river between present day Police Point and Strathcona Island. They chose to come to this spot, Thunder Bear maintained, since it was “very dangerous territory” and subsequently the last place that the chief would expect to find them. On their fifth day on the island, the water level began to rise, and so they crossed to the south shore (Strathcona Island) and pitched their teepee at the foot of the cliffs.

Silver Rose knew that Red Deer had a love of display and a weakness for showy feathers, and so she instructed Thunder Bird to shoot down a number of eagles that were nesting in the cut banks overlooking the river. Using the finest tail feathers from seven of the best eagles, Silver Rose made “one of the most beautiful bonnets any chief ever possessed”.

Thunder Bear and Silver Rose returned to Red Deer’s camp and presented the headdress to the old chief as a peace offering. The chief was so pleased with the gift that he forgave them both, and allowed them to remain together and live in his camp. The Cree people, being very superstitious, believed that Red Deer’s change of heart was attributable to the magic the medicine hat possessed.

Upon hearing Thunder Bear’s tale, Van Horne immediately decided to name the site of the new railway station ‘Medicine Hat’.

Legend 12: The Cree Sacrifice Legend

Background

Professor Robert Gard, Director of the University of Alberta’s Folklore and Local History Project, compiled the recollections of Alberta old-timers in his book Johnny Chinook: Tall Tales and True from the Canadian West (1943-1945). In his book, Gard included the story he was told in connection with the naming of Medicine Hat. This version can perhaps most accurately be regarded as the Cree sacrifice legend.

Professor Robert Gard, Director of the University of Alberta’s Folklore and Local History Project, compiled the recollections of Alberta old-timers in his book Johnny Chinook: Tall Tales and True from the Canadian West (1943-1945). In his book, Gard included the story he was told in connection with the naming of Medicine Hat. This version can perhaps most accurately be regarded as the Cree sacrifice legend.

The Legend

Many years ago, before the coming of the white man, a great chief named Kinosota ruled a band of Cree. Under Kinosota’s command was a wise, ambitious young brave named Kausketo’opot. In spite of his youth, Kausketo’opot was a veteran of many battles and was to be the successor of the old chief in the event of his death. Kausketo’opot had two wives. The first, whom his father insisted he marry at a young age, did not arouse his interest. The second, a girl named Wapasoos who was the daughter of the great chief Kinosota, was the love of his life. Shortly after he married Wapasoos, war was declared on the Blackfoot, and Kausketo’opot had to leave his teepee in order to lead his warriors against the enemy.

After many days of riding through the freezing prairie, the band arrived at present day Medicine Hat and made camp by the river, at the site on which the North West Mounted Police would later build their barracks (now marked by a sign in Police Point Park). Kausketo’opot rode downriver a short ways and came to the part of the South Saskatchewan River that remains free of ice all year round (between Police Point and Strathcona Island). According to Indian tradition, that stretch of the river was the breathing place of the Great Spirit. Kausketo’opot led his horse over to the water to drink. As the horse quenched its thirst, the Great Spirit, in the form of an enormous serpent, rose up from the icy water. The serpent spoke to Kausketo’opot, telling him that he would make him a great chief if he sacrificed his wife, Wapasoos, and threw her body into the opening in the ice.

Kausketo’opot returned to camp and told Kinosota, his chief, mentor and father-in-law, what had happened at the river. The chief listened in silence and, after thoroughly considering the situation, declared that it was for Wapasoos to decide what would happen. Wapasoos, after hearing the story, immediately agreed to be sacrificed for the sake of her husband. Kausketo’opot, however, was reluctant. Upon seeing her husband’s reluctance, Wapasoos began to plead fervently and incessantly. Although Kausketo’opot put up a fight, his wife’s entreaties and the power of his own ambition eventually proved to be too strong for him. The young brave picked his wife up in his arms, carried her to the river and hurled her into the swirling waters, where she was swallowed up. Overcome with grief, Kausketo’opot buried his face in his hands and sunk to his knees, where he remained for some time. Eventually, the serpent appeared again and spoke to him, telling him that a medicine hat lay under a fallen cottonwood tree by a spring about a mile and a half upriver. The headdress would make him a great medicine man and warrior, and would ensure his success in the upcoming campaign against the enemy.

Kausketo’opot travelled upriver and found, as the serpent foretold, a medicine hat underneath a fallen cottonwood tree. When he returned to the camp with the hat, there was a great powwow and war dance. In the midst of all this, the Blackfoot came upon the Cree unaware and ambushed them. The Cree were forced to cross the river. That night, the Cree decided to get back at the Blackfoot. Using rocks and earth, they built seven humanlike figures and stuck feathers in their heads. Then they made a campfire in the midst of them. When they had finished their handiwork, they retired to the cover of the trees and waited. After some time, the Blackfoot wandered by to inspect the scene. The Cree sprang from concealment and attacked. Many Blackfoot warriors were killed in the initial assault. The survivors fled across the river and scattered.

Legend 13. The Piikani (Peigan) Blackfoot Legend

Background

Jack Fuller, an amateur Albertan historian interested in Indian lore, recorded another explanation for Medicine Hat’s name in 1946. Fuller heard the explanation from his friend Red Buffalo, a Peigan Blackfoot from Cardston, Alberta. In the hopes of winning a contest organized by the Medicine Hat Chamber of Commerce, Fuller submitted his story, along with a watercolor of an Indian headdress.

The Legend

Many winters ago, before the coming of the white man, a band of Peigan Blackfoot were camped on the South Saskatchewan River near present day Medicine Hat. In those days, the Indians of the plains were without horses, and so they could not carry enough food with them to survive the winter. Instead, they depended almost entirely on fresh game during the cold winter months. Buffalo, the Blackfoot’s primary quarry, migrated south during the winter, often travelling in close proximity to the river (the buffalo’s old migration route is roughly followed by the Alberta Highway 41, or the “Buffalo Trail”, which begins just north of Bonnyville and ends on the American border just northwest of Havre, Montana). The buffalo, afraid to cross the ice, often accumulated in the river bend where the east-running South Saskatchewan River turns north (Medicine Hat). There, Indian hunters could make short work of the buffalo and survive the winter.

This particular winter, however, was especially severe. The winter had taken its toll on the buffalo population, and so the Peigan were forced to turn to alternative sources of sustenance like deer, rabbits and prairie chickens. Although prairie Indians would typically avoid eating fish, as they regarded underground and underwater creatures with fear, these Peigan realized that even a fish would fill a hungry belly. After several hunters unsuccessfully tried to spear fish through openings in the ice, an old man, who had travelled many trails, spoke of how the tribes to the south caught fish. These tribes, he said, would wait until nightfall before lighting torches, which they would hold above the water on the side of their canoes. The fish would swim up towards the light, where they could be caught more easily. Many of the superstitious Peigan felt that venturing out onto the ice at night was bad medicine, and so few volunteered for the job. One young woman, however, along with her grandmother, agreed to go out onto the ice. This young woman loved one of the braves in the tribe, but had been forced to marry an older chief at her father’s insistence. Several days earlier, the chiefs announced that they would hold a sacred dance intended to bring luck to the hunters, and so the girl secretly made a red-dyed porcupine quill headdress for her lover to wear at the dance. She kept this headdress tucked into her bosom for fear that her father might find it.

The night before the dance, the girl and her grandmother ventured out onto the ice, one with a torch and the other with the spear. The rest of the tribe watched fearfully from the shore in superstitious anticipation. As soon as the women leaned over a hole in the ice with their torch, the ice underneath them cracked. There was a shriek, a loud noise and then a huge burst of fire that lit up the entire width of the river. In an instant, the flame died out and the two women were nowhere to be seen. The next morning, when the men of the tribe went to search for the women, they found only the young woman’s red porcupine headdress laying on the ice at the water’s edge among a pile of ashes.

Legend 14: Saamis Teepee Legend

Background

In 1991, when the Saamis Teepee that had once stood in Calgary Olympic Park was re-erected above the Saamis archeological site in Medicine Hat, another story explaining the origin of the name Medicine Hat emerged. This story was told by Dan Weasel Moccasin, a Blood Elder, and was immortalized in a didactic label inside the Saamis Teepee. Variations of Weasel Moccasin’s legend had been told several times in the past. From 1903-1907, American anthropologist Clark David Wissler spent time among the Blackfeet of Montana and the Bloods, Peigan and Siksika Blackfoot of Alberta. During his time among the Blackfoot, Wissler recorded a similar story to Weasel Moccasin’s in his article, Mythology of the Blackfoot Indians, for the American Museum of Natural History. Two earlier story bearing resemblance to Weasel Moccasin’s legend were respectively documented by men named Paul Wolf and Joe Little Chief. It is also interesting to note that Weasel Moccasin’s legend is vaguely similar to the story of Thunder Bear, told by McKay and Sallows.

The Legend

Long ago, a Blackfoot named Eagle Birth (Eagle-Bull in Wissler’s Version, Black Eagle in Wolf’s Version) ran off with another man’s wife. Together, they came to what is present day Medicine Hat. One day, Eagle Birth’s woman saw an enormous headdress among the river cliffs. Each of the headdress’ feathers were as long as a man. The woman showed Eagle Birth the headdress, but upon closer inspection they discovered that it was only a huge piece of sagebrush. That night, Eagle Birth dreamed that a merman spoke to him, offering to make him a better hunter in exchange for a human to eat. Upon awakening, Eagle Birth resolved to accept the merman’s offer. He didn’t want to sacrifice his lover, however, and so he killed his dog, dismembered it, and threw its body into the river. The dog’s carcass had hardly touched the water before it was flung out onto the shore. The merman, apparently, was displeased with the substitute. The next day, after being visited again by the disappointed merman in his dreams, Eagle Birth set out to find a solution. As he was contemplating, he happened upon a starving stranger wearing a lynx hat. After conversing with the stranger via sign language, Eagle Birth discovered that he was a member of the Snake tribe, and therefore a bitter enemy of the Blackfoot. Eagle Birth, desperate to appease the merman, invited the Snake to eat with him in his teepee. Along the way, the Snake stopped for a drink by the river, and as he did so Eagle Birth grabbed a large stone and clubbed the Indian to death. Eagle Birth dove into the river with the body and discovered a large teepee beneath the water. Inside the teepee, he saw the merman from his dreams. Eagle Birth entered the teepee and presented the Snake’s body to the merman. True to his word, the merman bestowed Eagle birth with special hunting powers.

Before he could leave the underwater teepee, however, Eagle Birth was approached by an otter. After a brief conversation with the otter and the merman, Eagle Birth discovered that this otter was regularly drowning his fellow Blackfoot upriver near present day Lethbridge. Eagle Birth took the lynx hat off the dead Snake and presented it to the otter as a gift. The otter was so pleased that he gave Eagle Birth permission to draw the waves of the river on his teepee. With his new powers, Eagle Birth killed many animals and eagles. His lover tanned the hides and then selected the finest eagle tail feathers, working them into a headdress that resembled the sagebrush headdress they had seen on the cliff. Eagle Birth instructed his wife to present the feathers and hides to her husband as a gift. The husband accepted the gifts and made peace with Eagle Birth, who then built a teepee and painted it with the waves of the river. From that point on, the site of Eagle Birth’s adventure was known as Eagle Tail Feather Headdress, or Medicine Hat.

Landmarks

Some people suggest that Medicine Hat was named after a cliff or hill in the area that bears the resemblance of a Medicine Hat. The most common of these claims are described below.

Legend 15. A Hill East of the City Looks Like a Medicine Hat

One of the earliest claims that Medicine Hat was named after a landmark comes from a marking on a map that was completed in 1883, the year that Medicine Hat was founded. On the 1883 Department of the Interior map, there is a small hill in southeast Alberta labelled ‘Medicine Hat’ that happens to lie just east of the present-day city that bears its name. Some people claim that this hill is Medicine Hat’s namesake. Although there are a number of different explanations as to why the hill was labelled ‘Medicine Hat’, one of the most prominent explanations is based on the alleged account of Corporal Walter Johnson, a North West Mounted Police officer. According to this supposed account, Johnson was searching for a place to build a homestead after his discharge from the service in 1882. One day, while he was riding across the prairies near the South Saskatchewan River, he was joined by a lone Blackfoot warrior. The warrior pointed out the aforementioned hill, which looked vaguely like the headdress of a medicine man, and called it “Saamis”, which is the Blackfoot word for such a headdress. Johnson subsequently took out an entitlement and built a log cabin in the shelter of the hill, which he named ‘Medicine Hat’ after the Indian’s suggestion.

Legend 16. The South Saskatchewan River Valley Looks Like a Medicine Hat

Some anecdotal accounts maintain that Medicine Hat was so named because the valley of the South Saskatchewan River that runs through it looks the feathers that trail from a medicine man’s hat.

Legend 17: The Badlands Guardian

Although certainly not a traditional explanation for the naming of Medicine Hat, the existence of the Badlands Guardian is an interesting coincidence. Discovered in 2006 on Google Earth, the Badlands Guardian is a valley less than 50 km east of Medicine Hat (closer to Walsh, Alberta) that, when viewed from above, bears a strong resemblance to the head of an Indian medicine man wearing a plumed headdress. With its gaze towards Medicine Hat, the Badlands guardian almost suggests a mystical connection between the land itself and the Indian legends that surround it.

Although certainly not a traditional explanation for the naming of Medicine Hat, the existence of the Badlands Guardian is an interesting coincidence. Discovered in 2006 on Google Earth, the Badlands Guardian is a valley less than 50 km east of Medicine Hat (closer to Walsh, Alberta) that, when viewed from above, bears a strong resemblance to the head of an Indian medicine man wearing a plumed headdress. With its gaze towards Medicine Hat, the Badlands guardian almost suggests a mystical connection between the land itself and the Indian legends that surround it.

Legend 18. (Edit September 2017) Bob Edwards’ Version

A small paragraph in the very first edition of the magazine Alberta Folklore Quarterly (published March 1945) describes yet another legend pertaining to Medicine Hat’s naming. According to a journalist named Bob Edwards, an Indian camping by the South Saskatchewan River on a night many years ago noticed that the moon cast a strange-looking shadow on the ground. The shadow was somewhat akin to the shape of a medicine man’s headdress. After the Indian related the story to his band, the place at which he saw the moon’s shadow was dubbed ‘Medicine Hat’.

Sources

- · But Names Will Never Hurt Me, 1993, Marcel M.C. Dirk

- · All Hell For a Basement, 1981, Ed Gould

- · Saamis: The Medicine Hat, 1967, Senator F.W. Gershaw

- · Indian Tales of the Canadian Prairies, 1894, James Francis Sanderson

- Alberta Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar. 1945), Robert E. Gard

Other Reading

- · Myths and Legends Beyond Our Borders, 1899, Charles Montgomery Skinner

- · Broad Horizons, 1919, W. Everard Edmonds

- · Early History of the Medicine Hat Country, 1923, James William Morrow

- · Prairie Place Names, 1934, Edna Baker

- · Johnny Chinook: Tall Tales and True from the Canadian West, 1967, Robert

Comments on the Original Article

Dr. Moira McCutcheon

I am a daughter of Robert McCutcheon, grandson of Sgt Robert McCutcheon & Angeline Gaddy, of Medicine Hat. I know little of my history and found this website very interesting.

Malcolm

Just discovered your site and name origins for Medicine Hat. Good job! There is another legend researched and carved in brick by local artist Jim Marshall (mural is in City Hall). It involves a Blackfoot who sacrificed his wife to the river god in order to learn how to find food for his band in a cold winter. He was directed to make a feathered bonnet from eagle feathers to be found in the cliffs above the river. I have heard also that Saamis might be more like Sa’amis. Little Corn was a close associate of my great-grandfather James Hargrave.

Brian Starnes

Great grandfather was Robert Watson, he came with the NWMP in 1875 to fort Walsh then to Medicine Hat where he lived until he passed away in 1901.

He built the Palace Stable and livery and was the first WATER man in town.

Great site you have.

Emily Peterson

The Legend Behind ‘Medicine Hat’ Medicine Hat inherited its name from the native word “saamis” which means medicine man’s hat. A number of legends tell the story of how this city was named. One of these legends is beautifully depicted in a sculptured brick mural at City Hall. Brick Mural of Medicine Hat Name Legend The legend tells of a winter of great famine and hardship for the Blackfoot nation. The elders of the Council chose a young man to save his tribe from starvation. Setting out with his new wife and favourite wolf dog, he journeyed down the ice-bound South Saskatchewan River. After many arduous days they made their way to the “breathing hole” an opening in the ice, located on the river between what is now Police Point and Strathcona Park in Medicine Hat. This location was a sacred place to the First Nations’ people: a place where the water spirits came to breathe.

James Garry Horner

David Edson Horner was my Grandfather and James Henry Horner was my Great Grandfather.

Kathy

dozens of my family is buried and born here. they were the renners, leippies, westwoods. loved hearing about the old stories…i spent many memorial summers here int the 60;s and 70’s..