The following article was originally published on my personal website in 2014.

The Mounties’ Great March West

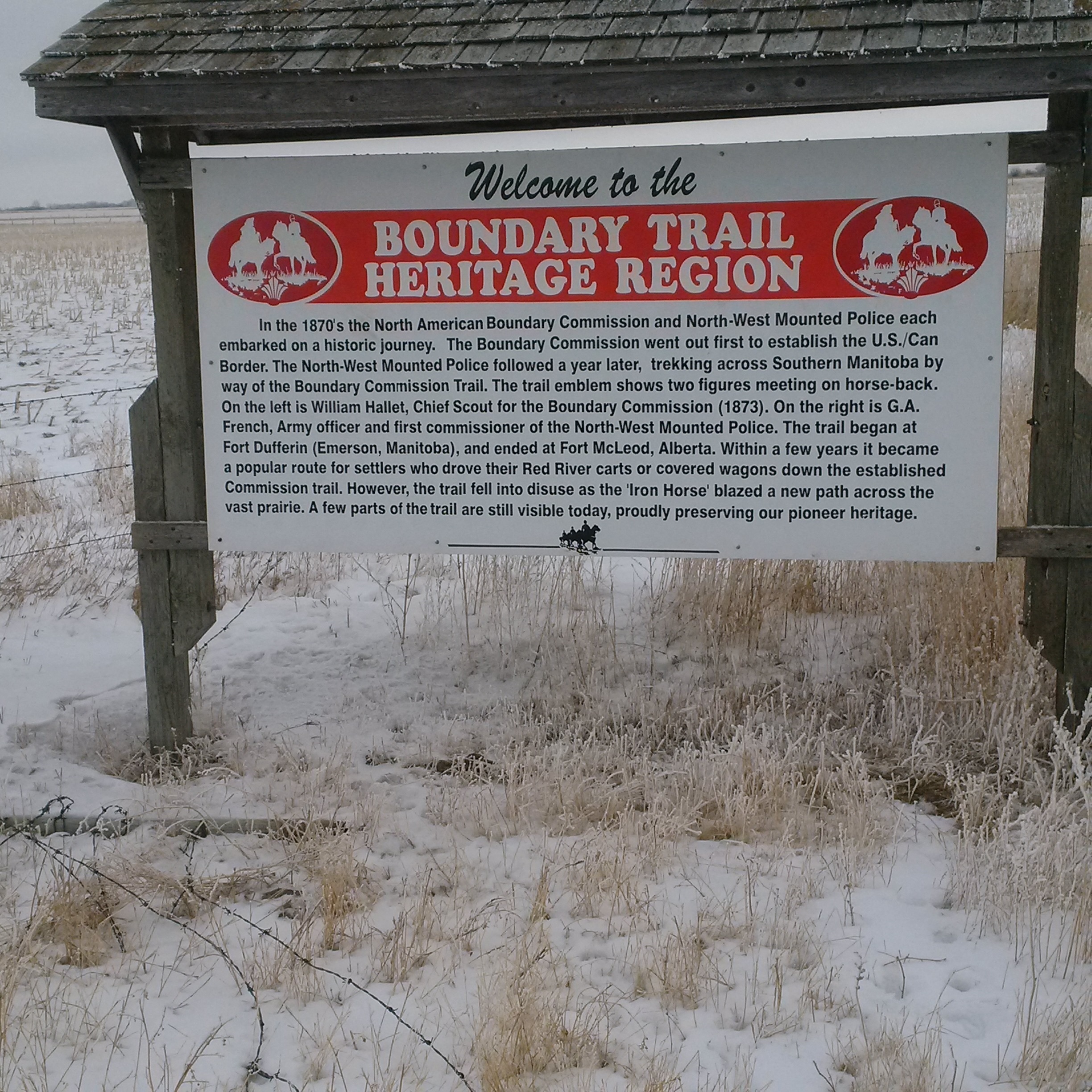

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Canada? Although I don’t have any statistics on hand, I’d venture to guess that, for many people, the answer to that question would be one of five things: 1) maple leaves/ syrup; 2) hockey; 3) beavers; 4) beer 5) Mounties. Of these five classic Canadian icons, only Mounties- made famous by Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, Dudley Do-Right, and other ‘Mounted Police characters, both fictional and fact-based, portrayed in TV shows, novels and Hollywood Northwestern films- are unique to Canada. Today’s Mounties- Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers who, with the exception of those standing guard on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, have long since exchanged the red serge and white pith helmet of their precursors for the darker uniforms favored by police officers around the world- can typically be found policing rural areas and stretches of Canadian highways. One such highway, the Interprovincial “Red Coat Trail” that runs through Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, marks the approximate route of the famous “Great March” of 1874, the 1300-kilometer-long trek of Canada’s first Mounties, the North West Mounted Police, from Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, to the lawless Canadian West. Several Mounties who participated in this “Great March”- including George French, Henri Julien, Sam Steele, Cecil Denny and Fred Bagley- documented their experiences. The following is a summary of their collective stories.

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Canada? Although I don’t have any statistics on hand, I’d venture to guess that, for many people, the answer to that question would be one of five things: 1) maple leaves/ syrup; 2) hockey; 3) beavers; 4) beer 5) Mounties. Of these five classic Canadian icons, only Mounties- made famous by Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, Dudley Do-Right, and other ‘Mounted Police characters, both fictional and fact-based, portrayed in TV shows, novels and Hollywood Northwestern films- are unique to Canada. Today’s Mounties- Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers who, with the exception of those standing guard on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, have long since exchanged the red serge and white pith helmet of their precursors for the darker uniforms favored by police officers around the world- can typically be found policing rural areas and stretches of Canadian highways. One such highway, the Interprovincial “Red Coat Trail” that runs through Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, marks the approximate route of the famous “Great March” of 1874, the 1300-kilometer-long trek of Canada’s first Mounties, the North West Mounted Police, from Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, to the lawless Canadian West. Several Mounties who participated in this “Great March”- including George French, Henri Julien, Sam Steele, Cecil Denny and Fred Bagley- documented their experiences. The following is a summary of their collective stories.

The Formation of the North-West Mounted Police

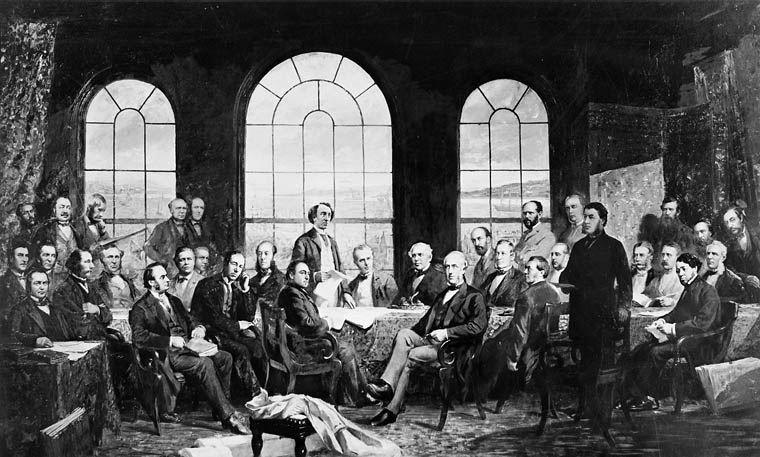

On July 1, 1867 (the very first “Canada Day”), British-controlled Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada (a territory consisting of parts of present-day Ontario and Quebec) coalesced to form the Dominion of Canada. This embryonic Canada was a small country that skirted the northern shore of the Great Lakes and surrounded the St. Lawrence River Valley. Its first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, endeavored to make Canada a massive state, as vast as the Russian Empire, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and north to the Arctic Ocean. To accomplish this, Macdonald knew that the Province of British Columbia (present-day British Columbia) – an isolated British territory that ranged from the Northwest Coast to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains- would first have to accept the terms of the Canadian Constitution- an unlikely event unless the Province of British Columbia and the Dominion of Canada were bridged by a trans-continental railroad. In order to build such a railroad, the Dominion would have to own the land in between- an enormous, wild territory known as Rupert’s Land. Rupert’s Land, at that time, was controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), one of the oldest commercial corporation in the world. In fact, Rupert’s Land had belong to the HBC since its inception nearly 200 years earlier, in 1670 when Charles II- King of England, Scotland and Ireland- gave the company a monopoly in the area. In the spring of 1869, the British Crown, at the entreaty of the Dominion of Canada, reclaimed Rupert’s Land, as well as the North-West Territory (the continental mainland north of Rupert’s Land and the Province of British Columbia) from the HBC. Later, on July 15, 1870, the Dominion of Canada, with permission from the British Crown, purchased the two regions for 300 000 pounds sterling and amalgamated them into the expansive “North-West Territory”. Ever since the end of the American Civil War (1865), the United States had shown interest in acquiring Rupert’s Land. For Canadian bureaucrats, this was a disturbing notion indeed, given the concept of “Manifest Destiny” and United States’ recent acquisition of the Oregon Territory from the British Crown and annexation of Texas and California in the aftermath of the Mexican-American War. Prime Minister Macdonald knew that he needed to populate Canada’s new North-West Territory with settlers if he hoped to keep it, along with his plan for a transcontinental Canada. He also knew that the newly-formed Dominion of Canada did not have the resources to wage wars against hostile Indians opposed to white encroachment on their hunting grounds, as the United States had in the American Northwest Territory, the Old Southwest and, more recently, in Dakota and Montana Territory; Macdonald knew that the Dominion of Canada would have to bring law and order to the area before settlers arrived, and that a troop of mounted riflemen, like the Irish Constabulary, would be ideal for the job. Macdonald’s plans to create this mounted police force were dashed when Metis revolutionary Louis Riel, in an effort to establish a provisional government in the Red River Colony, led his Metis in the Red River Rebellion of 1869/70. In response, the Canadian government dispatched 1200 British and Canadian soldiers in the Red River Expedition- a peaceful military expedition partaken by several future Mounties, including Sam Steele and James Macleod. Only after May 1870, when the Manitoba Act pacified the disgruntled Metis by recognizing the Province of Manitoba, could Macdonald and his Conservative government return their attention towards the hypothetical police force. In the summer of 1870, the Canadian government heard rumors that American whisky traders, most of them from Montana, had crossed the 49th parallel into the North-West Territories (in what would become southern Alberta) and were trading rotgut “firewater” and repeating rifles to the local Blackfoot Indians. According to the United States Secretary of State, the Canadian Blackfoot, after purchasing these dangerous goods, would travel south into Montana to kill settlers and steal horses before returning north again. Despite the rumors, which reinforced the imperative of establishing law and order in the Canadian west, Macdonald, notorious for his procrastination, delayed the formation of the police force. Instead, he dispatched government agent Lieutenant William Butler to report on the situation that fall. Butler subsequently travelled to the North-West Territory, inspected the North Saskatchewan River Valley near Fort Edmonton, and returned with the recommendation that a cavalry regiment be sent out west to establish law and order. Instead of following Butler’s recommendation, Macdonald sent another agent, Colonel Robertson-Ross, to verify Butler’s claims. Robertson-Ross left his post at Fort Garry on August 10, 1872, inspected the North Saskatchewan River Valley, travelled through the Crowsnest Pass to the Northwest Coast, and returned to Ottawa in mid-December with a recommendation similar to Butler’s. In addition, Robertson-Ross suggested that the police force be dressed in British scarlet to starkly distinguish them from blue-coated American soldiers, whom the Plains Indians largely feared and despised. Delaying the inevitable even further, Macdonald decided to wait and see what Alexander Morris, the newly-appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories, had to say on the matter. Like Butler and Robertson-Ross, Morris maintained that a mounted police force needed to be dispatched to the North-West Territories in order to quell growing Native unrest. Faced with overwhelming evidence that a police force was needed in the Canadian west, Macdonald finally submitted a bill proposing a legislation enabling the establishment of such a force. On May 23, 1873, the bill received Royal Assent. The act was only an enabling legislation, and therefore the police would only come into being when authorized by the Cabinet. Worried that the police force would be an undue strain on the Dominion of Canada’s meager budget, Macdonald, ever the laggard, decided to postpone the authorization. In the late summer of 1873, news of the Cypress Hills Massacre reached Ottawa. For the Canadian government, procrastination was no longer an option, and on August 27, 1873, the North West Mounted Police, a troop of three hundred red-coated riflemen, came into being.

Recruitment and Training

It took nearly a year for the Canadian government to assemble the 300-man North West Mounted Police, which was to be divided into six divisions of 50 men: Troops A, B, C, D, E, and F. First, Macdonald and his Cabinet hand-selected some of the officers who would lead the force. These first officers, all of them military men of high social standing, included: James Farquharson Macleod, a well-educated lawyer and a veteran of the Red River Expedition; James Morrow Walsh, a distinguished military academy graduate, cavalry commander, and hotel manager; William Drummer Jarvis, a militiaman nephew to Hewitt Bernard, the Deputy Minister of Justice; Charles F. Young, a veteran of the British Army; Ephrem A. Brisebois, a veteran of the American Civil War and the Third Italian War of Independence (enlisted in the Union Army and Papal Zouaves, respectively) fluent in both English and French; William Winder, a former cavalry captain; Jacob Carvell, a Confederate veteran of the American Civil War; John Breden, a young man with political connections; and Edmund Dalrymple Clark, a relative of the Prime Minister. In the fall of 1873, these newly-appointed officers were tasked with recruiting troopers, as well as other officers, throughout the Dominion of Canada. The recruits were to assemble in Collingwood, Ontario, on the southern shore of the Georgian Bay, and make the journey to Lower Fort Garry, Manitoba, via the Old Dawson Trail before winter set in, making the route impassable. Winter was fast approaching and time was of the essence, and so the officers took their recruits’ supposed qualifications at face value without taking the time to verify them. As the officers would learn several months later, many of these recruits had never ridden a horse or fired a rifle. Soon, half of the ranks- Divisions A, B, and C- were filled, and the 150 men assembled at Collingwood. Throughout early-mid October, each of the three troops, one by one, left the Ontario town by steamboat and made the miserable, grueling journey down the Old Dawson Trail, the 880 kilometre land and water route that linked the Great Lakes with the prairies of the North-West Territory. The Mounties arrived at Lower Fort Gary throughout the spring and winter of 1873/74. While the recruits were traversing the Old Dawson Trail, Macdonald and his Cabinet selected the force’s Commissioner, a British Army officer named George Arthur French. French- an Irish contemporary of Kootenai Brown with some experience in the Irish Constabulary, the model upon which the NWMP was designed- was the head of the Kingston School of Artillery and a veteran of the Maori Wars in New Zealand. Exemplary of the British military elite, French was a firm proponent of a strict and clear-cut chain of command; he believed that it was the superior’s duty to remain aloof of and maintain a strictly martial relationship with his subordinates, and that it was the subordinate’s duty to follow a superior’s orders without question. In November 1873, after all the recruits had arrived at Lower Fort Garry, a daily routine was implemented. From 6:00 am until 10:00 pm, the troopers drilled both on foot and on horseback. Although the foot drills transpired largely without incident, the riding drills were another matter entirely. Many of the recruits had never ridden a horse before, and their inexperience, coupled with the fact that the training mounts consisted of 30-some unbroken western mustangs, made the first few riding drills trying experiences. Sam Steele and James Walsh, who were tasked with whipping the raw recruits into competent horsemen, initially had the troopers ride bareback, without stirrups or reigns. Few of them remained seated. The officers, sympathetic to their men’s plight, covered the frozen training ground with fir branches to break their falls. Steele and Walsh drilled the troopers relentlessly, and by mid-December, when training was discontinued on account of the freezing temperatures, the recruits had become, according to Steele, “very fine riders.” Any progress the officers might have made instilling discipline in the recruits in the fall, however, was nullified in the long winter that followed. With little to do, the troopers turned to drinking and gambling to alleviate their boredom. Commissioner French, after arriving at Lower Fort Garry in mid-December, admonished the troopers for their misconduct and banned alcohol from entering the fort. Throughout the winter and early spring, a number of disenchanted trainees deserted, resigned or were dismissed. Among them were Cabinet-appointed officers Young and Breden, along with new officers Joseph Forget and Duncan B. Additional men were promptly recruited to fill the ranks. Among these new officer were Francis Dickens, son of the famous Victorian novelist Charles Dickens, and Joseph Francis, a veteran of the Crimean War. In February 1874, Commissioner French, accompanied by William Jarvis and newly-appointed officer James Walker, returned to Ottawa to secure previously-ordered supplies. Among these supplies were several hundred horses. Instead of ordering western mustangs already adapted to a diet of prairie forage, French, convinced in the importance of the force’s professional appearance, ordered several hundred physically imposing stable-raised thoroughbreds, along with 400 000 pounds of oats. Officers Jarvis and Walker, meanwhile, set about recruiting the second 150-man half of the force- Divisions D, E, and F. Unlike the first wave of recruits, these men, once assembled in Toronto, thanks to the courtesy of the American government, had the luxury of travelling by train to Fargo, Dakota Territory before marching about 340 kilometres north to Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, thereby avoiding the dreaded Old Dawson Trail entirely. Divisions A, B, and C, garrisoned in Lower Fort Garry, made the short 25 kilometer march south to Fort Dufferin to join them.

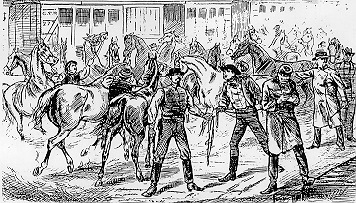

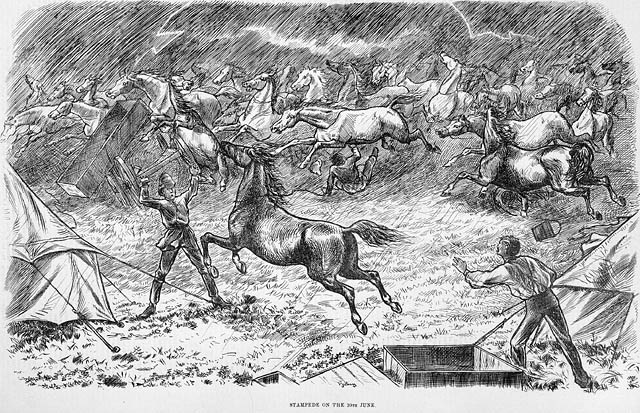

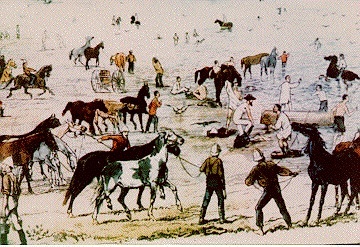

Divisions D, E, and F arrived at Fort Dufferin on June 19, 1874, where Divisions A, B, and C were waiting for them. The following day, on June 20, the North West Mounted Police, finally assembled as a single unit, experienced one of the worst storms in Manitoban history. According to Sam Steele:

“A thunderbolt fell in the midst of the horses. Terrified, they broke their fastening and made for the corral. The six men on guard were trampled underfoot as they tried to stop them. The maddened beasts overturned the huge wagons, dashed through a row of tents, scattered everything, and made for the gate of the large field in which we were encamped. In their mad efforts to pass they climbed over one another to the height of many feet… The stampede continued south across the Pembina bridge. Crazed with fright the horses crossed the river and continued their flight on the opposite bank, and the majority was between 50 and 80 kilometers in Dakota before they were compelled by sheer exhaustion to halt.”

The next day, the weary trainees rounded up the scattered horses. The weeks following the storm were characterized by final preparations for the journey west. Wagonloads of supplies arrived from the southern Boundary Commission on the Canadian-American border. The supplies included a large quantity of flour, a replacement for flour lost on the Red River on the journey from Fargo. Although the Mounties also lost a large quantity of oats on the Red River, the Boundary Commission was unable to procure a replacement, a misfortune that would prove disastrous for the force’s mounts several months later. Also among the supplies were crates of ammunition and British Army surplus Snider-Enfield carbines and 330 Adams revolvers, many of which, due to poor packing, had been damaged or destroyed en route to Fort Dufferin. Although most of the men were subsequently equipped with the rifles- many of which, on account of their condition, had to be converted to breech-loaders- few were equipped with serviceable side arms.

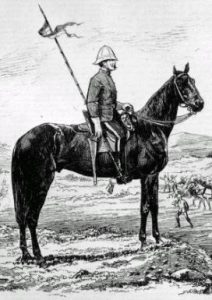

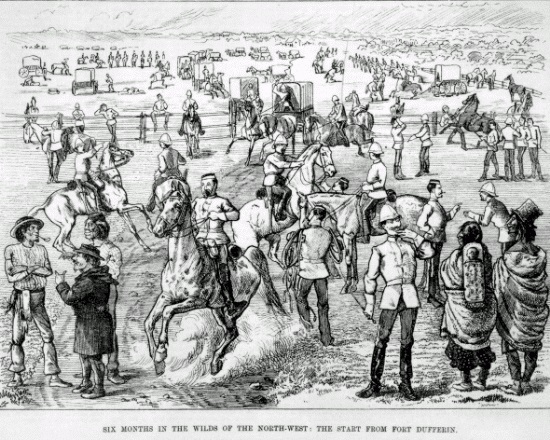

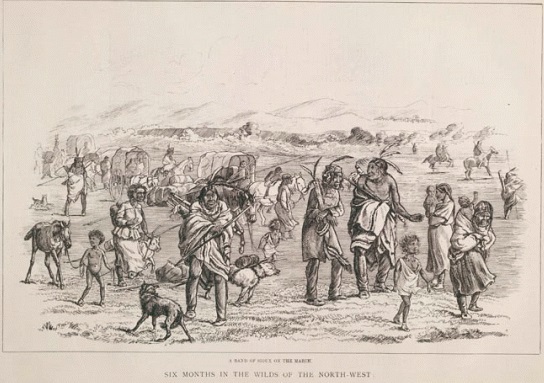

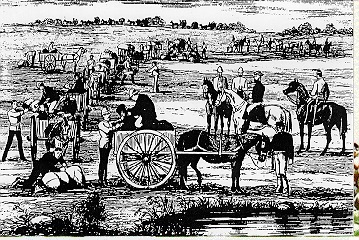

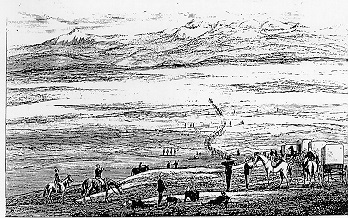

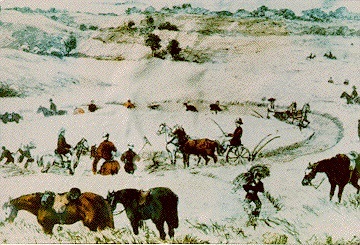

Finally, on July 8, 1874, the 300 Mounties- decked in scarlet woolen jackets, gray breeches, black leather boots, tanned leather gloves and white pith helmets- along with an auxiliary of Metis scouts and cart drivers, a small herd of cattle, two nine-pounder cannons (each weighing 3800 pounds), 73 wagons, and 114 Red River carts filled with supplies, rode out of the Fort Dufferin Commission Campground. With orders to march on Fort Whoop-Up, the whisky fort around which much of the Canadian West’s lawlessness was said to revolve, the Mounties embarked on their Great March West.

Fort Dufferin to the Souris River

Day 4

The Mounties, arranged as they were in a three-kilometre-long column, travelled without much event for several days. Near the end of the fourth day, they reached a Metis settlement known as Grant’s Place, where they decided to stop for the night. There, they learned that a war party of Sioux had raided the Metis village of St. Joe, located about eight kilometres south.

That evening, many of the troopers- after visiting a tavern owned by a Metis named Charles Grant, the namesake of the community- came upon a shallow pond populated with a large number of ducks. Immediately, they set about dispatching the birds with impromptu clubs. Commissioner French was informed of the incident, and tasked Assistant Commissioner Macleod with disciplining the troopers involved. Although Macleod dutifully placed a number of the troopers on report, he also, in a display unorthodox empathy that would earn him popularity with his subordinates, ensured that none of the troopers involved went without their share of duck. The ensuing feast was a welcome reprieve from hardtack.

Day 5

At the end of the day, the force made camp at the base of the Pembina Mountains. That night, the Mounties, or more accurately the Mounties’ canvas tents, were assailed by a swarm of grasshoppers. The troopers packed the tents quickly to prevent their ingestion.

Day 7

On Tuesday, July 14, the Mounties forded the Pembina River at Pembina Crossing without event. That day, they were joined by the Metis scout Pierre Leveille, their chief guide and interpreter, who came bearing gifts for the First Nations the Force would inevitably encounter on their Great March West.

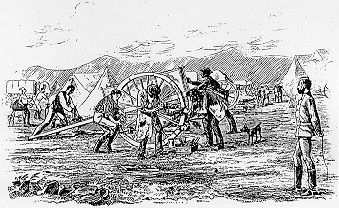

Day 12

On Sunday, July 19, the Force, in accordance with French’s order that the Holy Sabbath be observed, stopped for a day of rest on the Souris River. There, for the first time in two weeks, the men had the opportunity to bathe, and to wash the horrific product of so-called “prairie cholera”- a gastrointestinal malady that followed the feast of duck and prairie pond water at Grant’s Place- off their soiled breeches and saddles. The much-needed break also gave the Force’s blacksmiths and wheelwrights time to repair damaged equipment. The restorative effects of the day’s rest were supplemented with generous rations of freshly-roast beef, supplied from the herd of cattle that French had insisted accompany the Force.

Souris River to Old Wives Lake

Day 15

On July 22, the Mounties forded the Souris River, again without incident, partly thanks to the adroitness of the Metis drivers and guides. However, the day was particularly hot, and after fording the river, two horses, too weak to continue, were abandoned. Two other horses died.

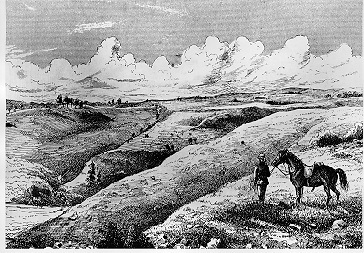

The poor condition of the horses was later attributed in part to the ration restrictions necessitated by the small supply of oats. Even had the thoroughbred horses the ability to stomach prairie forage, they had no opportunity to so supplement their meager diet; the grasshoppers that had assailed the Mounties on Day 5 had left the prairies west of the Pembina Mountains almost completely barren, punctuated by the occasional portentous buffalo skeleton.

Day 16

On the sixteenth day, the Mounties travelled past a clay-topped hill known to the Metis as Butte Marguee (known today as Scout Hill). The butte, the Metis explained to any troopers interested enough to listen, was the site where a Plains Cree brave, many years earlier, snuck up on a Mandan scout and clubbed him to death with a rock. To commemorate his deed, the Cree, using a tomahawk, carved an augmented impression of the dead warrior in the clay. He also dug giant footprints up the side of the hill, symbolizing his stealthy ascent. The Metis who told the story led a number of curious troopers to the site. Sure enough, a number of large footprints led up the hill to a where huge impression of a prostrate warrior was carved at the top. Eerily, the man-shaped hole at the top was littered with rocks covered in red lichen, suggestive of the blood that had been spilt there many years prior. Later that evening, the Force made camp near the dry Riviere des Lacs.

Day 17

The next morning, the troopers and their parched horses, guided by Metis scouts, made the short journey to St. Peter’s Spring, a nearby watering hole. To their dismay, the Mounties discovered that the hole was dry. At the encouragement of Sam Steele, the troopers began digging into the muddy depression until they were rewarded with water clear enough to drink.

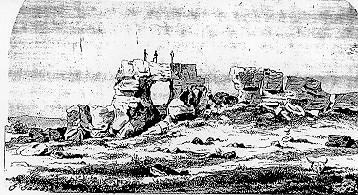

After the horses had quenched their thirst, the Mounties travelled farther west to La Roche Percee, a massive sandstone arch beneath which, the Metis maintained, was a giant subterranean cavern in which various First Nations people, over the years, had hidden from enemies. True or not, none of the curious troopers were able to find the entrance to the mysterious cave. They did, however, find a number of Neolithic petroglyphs carved into the megalith’s exterior, along with the hand carved words, “And his Scouts 1865,” – words carved by scouts belonging to United States General George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry, the regiment which would meet its famous demise in three years at the hands of Sitting Bull’s Sioux. The Mounties travelled a short distance beyond La Roche Percee to Short Creek, where freshwater, firewood and forage were found in abundance.

Day 18

The next day, Sub-Inspector Albert Shurtliff, who had been earlier dispatched east with an order to return with horses and supplies, returned with far fewer horses and supplies than he had been initially ordered to bring. Shurtliff did, however, arrive with a cartload of pemmican, a nutritious prairie staple consisting of sundried, pulverized buffalo meat and rendered buffalo fat, coalesced into a greasy sludge. This solid, simple prairie food, while not especially delicious, was nonetheless a welcome supplement to the hardtack and tea that the Mounties had largely subsisted on since leaving Fort Dufferin.

Day 22

On July 29, after the Mounties reached Wood End Depot, French split up the Force. He directed officer Jarvis and Sub-Inspector Shurtliff to travel- along with 12 troopers from A Troop, 12 Metis, 55 of the weakest horses, 24 wagons, 55 carts, 62 oxen, 50 heads of cattle, nonessential supplies, six sick men and the Force’s quartermaster- to Fort Ellice, the HBC post situated at the confluence of the Assiniboine and Qu-Appelle Rivers, and then further northwest up the Fort-Garry-Fort Edmonton Trail to Fort Edmonton.

Day 23

On July 30, the Force camped on the shores of Long Creek, SK.

Day 25

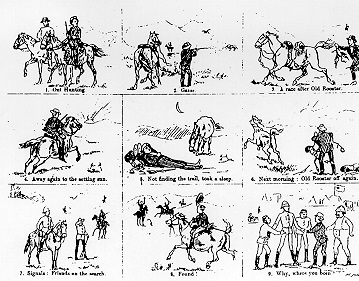

On August 1, Henri Julien- a Canadian Illustrated News artist who accompanied the Force in order to visually document their Great March West- left the Force’s main body for a brief duck-hunting excursion. After Julien dismounted to collect a duck he had shot, his horse rode off. Julien managed to catch up with and mount his horse after chasing it for hours on foot. Upon returning to the site of the camp, Julien discovered that the Mounties had long since departed. Exhausted, the artist dismounted, removed his saddle from his mount, tethered his horse and slept under the stars.

Day 26

The next day, at sundown, a search party discovered Julien, hungry and exhausted, his hands and feet ragged and bloody, his face disfigured by thousands of mosquito bites. That morning, upon awakening, he had discovered that his horse had broken free of its tether. He had spent most of day chasing down the animal, and had ridden it bareback back to the saddle when he finally caught it.

Day 27

On the 27th day, Sub-Inspector John Henry McIllree, a native of Kingston, Jamaica, and Commissioner French spotted antelope on the prairie. The two officers, eager to acquire fresh meat, cautiously stalked the animals. Sub-Inspector Cecil Denny, an Englishman of aristocratic stock, became aware of the discovery and, anxious to participate in the hunt, carelessly charged the officer’s quarry. The antelope, startled, promptly fled, much to the displeasure of McIllree and French.

Day 28

As punishment for his thoughtlessness the previous day, a chagrined Cecil Denny was assigned rear-guard duty at the dusty, nethermost end of the column. As it transpired, Denny, wallowing in mortification, spotted another antelope on the horizon. Determined to redeem himself, he inconspicuously broke ranks and pursued the animal. In the heat of the hunt, Denny, oblivious to all but his prey, unwittingly rode his horse directly into a patch of quicksand. As his horse began to sink into the mud, the Mounty became aware of his situation and, in a panic, launched himself from his saddle. Fortunately, he found himself on solid ground. His mount, however, was not so fortunate. Denny gazed helplessly as his horse, its eyes rolling with terror, continued to sink until only its head protruded from the mud. After trying unsuccessfully to drag the horse out of the quicksand by its bridle, Denny, now far from the Force’s main body, began to walk in what he believed to be its general direction. In the late afternoon, a weary Denny spotted two horses on the horizon, one of them straddled by a rider. After determining that the horseman was not an Indian, Denny called out to him. As it turned out, the rider was none other than Assistant Commissioner Macleod, whom Commissioner French had tasked with obtaining pemmican from the Wood Mountain Depot, along with a handful of other Mounties. Fortunately for Denny, Macleod had ridden ahead of the transport carts. After Denny told his tale to the Assistant Commissioner, the two men, the former having mounted Macleod’s spare horse, rode to the quicksand. There, they found Denny’s horse, half-submerged yet still alive. Using a lasso and the power of the two unencumbered horses, the Mounties hauled Denny’s horse from the mud. After giving the traumatized animal time to recover its wind and its wits, Macleod and Denny returned to Force before nightfall. Later that night, at about 1 am, a terrible thunderstorm reminiscent of the Fort Dufferin storm materialized. According to Henri Julien, the storm’s winds blew down most of the Mounties’ tents- though none of the Metis tents-, and would have scattered the horses had it not been for the pickets earlier erected by the troopers.

Day 32

On August 8, 1874, the Mounties came to an enormous saltwater lake home to huge populations of migratory waterfowl located south of present-day Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. The Metis guides and cart drivers explained to the troopers that the vast expanse of alkaline water was called “Old Wives Lake” by Cree and French/Scottish-Cree Metis. The Metis explained that, according to Cree legend, a Cree hunting party killed a large number of buffalo on the lake’s shore one spring in the early 1840’s. The Cree processed and packed the animals, and were just about to return home (in one version of the legend, the Cree came from the east of Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan; in another version, they hailed from the Qu’Appelle Valley) when they were attacked by an advance guard of Blackfoot warriors. The Cree successfully repelled the braves, who ostensibly returned to report their findings to a much larger Blackfoot war party.

That night, the Cree, certain that the Blackfoot would return at dawn in full strength, held a powwow. The chiefs knew that the fresh pemmican they had just processed, packed as it was onto horse drawn travois, would impede their progress immensely. They would either have to abandon the pemmican and return home unscathed but empty-handed, or make a stand and fight the warlike Blackfoot in the morning. Neither option was desirable. Then the old wives of the tribe spoke up, volunteering to stay behind in the lakeside camp while the rest of the Cree stole away in the night with the pemmican. They would tend the fires and talk loudly throughout the night so as to not arouse the suspicions of the Blackfoot scouts, who were surely watching the camp from concealment in the nearby hills. By the time the Blackfoot discovered the ruse, the Cree would be long gone. And so the old wives’ plan was adopted, and the Cree hunting party snuck away in the dark while the old wives stayed behind. At dawn, Blackfoot warriors thundered into the camp, screaming war whoops, only to discover that they had been duped. Furious, they tortured and slaughtered the old Cree women who had stayed behind. Legend has it that the spirits of the old wives have haunted the lake, or more specifically a large island in the middle of the lake (known today as the Isle of Bays) ever since. Some say that on windy spring nights, their ghostly voices carry across the water.

Old Wives Lake to the Cypress Hills

Day 36

In the late afternoon of August 12, 1874, after a long day’s march that involved grading a hill too steep for the horses, the Mounties made camp on Old Wives Creek a short distance from Old Wives Lake, at the approximate site of present day Mossbank, Saskatchewan. That evening, a Sioux chieftain, the first Indian the Mounties would encounter on their Great March, rode into the camp. After parleying with French, the Sioux rode away with a promise to return the following day with more of his kinsmen.

Day 37

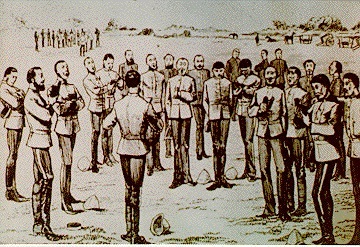

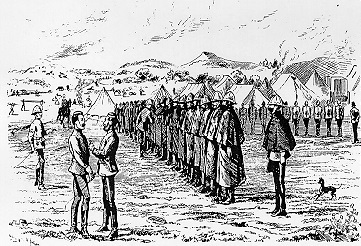

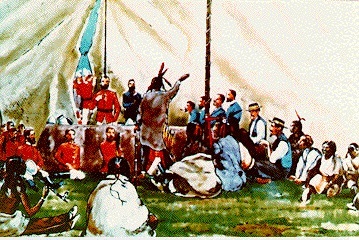

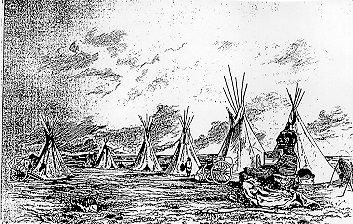

True to his word, on the morning of August 13, the Sioux returned to the Mounties with his 30-man band. An officer escorted the chief and his people to an open pavilion made from two conjoined tents. Seated behind a desk under the pavilion canopy was Commissioner French, who had donned his finest parade uniform for the occasion.

The chief and his braves- along with the NWMP high officers, who, at French’s behest, were also resplendent in full dress uniform- sat on the ground at the foot of the pavilion. The Sioux men arranged themselves in a quadrant, and their wives and children sat opposite them to form a semicircle facing the pavilion. After smoking and passing around a pipe as was Sioux custom, the chief and French exchanged words, with the Metis Leveille, the Force’s chief guide, serving as interpreter. French explained to the Sioux that the Mounties had come to bring Canadian law to the prairies by putting an end to the destructive whisky trade. The Sioux, who had grown to resent not only American soldiers but also the American traders who perpetuated the trade, welcomed the news. After the Mounties presented the Indians with gifts of calico, tea and ammunition, the Sioux, apparently convinced that the NWMP was a powerful and benevolent force, returned to their camp.

Day 38

On August 14, the Sioux returned to the Mounties’ camp to sing and dance for the troopers. After their performance, the Sioux left, only to return again later that evening, determined to trade. Many of the troopers, eager to acquire souvenirs of the Great March West, gladly parted with brass buttons, tobacco plugs and other menial items in exchange for moccasins and scalps.

Day 40

On August 16, the small Metis auxiliary that accompanied the force was augmented by the notable addition of Francis Morriseau, a Metis hunter from Fort Benton, Montana well acquainted with the western Canadian prairies. Morriseau brought with him disconcerting news that the Blackfoot to the west were warring with white traders.

Day 41

On August 17, Assistant Commissioner Macleod, whom French had once again charged with obtaining supplies from the Boundary Commission post at Wood Mountain, returned with oats, pemmican, a handful of western mustangs, and Captain Lawrence Herchmer, a Boundary Commission employee and an acquaintance of French. Herchmer, upon speaking with French, doubted Morriseau’s claim that the Blackfoot were on the warpath, as the Blackfoot Confederacy, due to the degenerative effects of the whisky trade, was now a mere shadow of its former self and currently in no position to wage war against well-equipped whites.

Day 42

On the 42nd day, the North West Mounted Police were assailed by a colony of belligerent flying ants.

Day 45

On August 21, somewhere near the site of present-day Chaplin, Saskatchewan, the Force happened upon a small party consisting of three men: Louis Leveille, the brother of chief scout Pierre Leveille; the Metis’ two sons, Paul and Gabriel; and a black-robed, French-Canadian Roman Catholic priest named Pere Lestaing. The four men were en-route to Fort Edmonton (in another account, they were heading east to Fort Garry). At French’s request, Lestaing agreed to hear the confessions of and say a Mass for the Mounties. Said Gabriel Leveille (one of Louis Leveille’s two sons) of the Mounties in a later reminiscence:

“They looked terrible. They wore little bits of hats no bigger than a plate. These gave no shade at all and their faces were burned almost black and they were all bitten by mosquitoes. The horses’ tails were bobbed right to the bone like they would be in England. The tail was thus no use to the horse to keep off the mosquitoes and the flies.”

Day 49

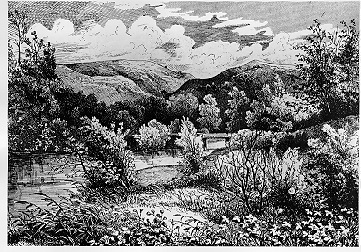

On August 25, 1874, the North West Mounted Police came to an oasis in the prairies: the beautiful wooded Cypress Hills. Commissioner French, having heard from the Metis guides that the Cypress Hills was a hotspot for First Nations violence, put the men on high alert. He distributed extra ammunition, supplemented the night guard, and ordered the Mounties to sleep fully-dressed with their rifles at hand. In spite of the danger, the troopers, elated at the change of scenery, spent their free time hunting, searching for Indian artifacts, and ostensibly revelling in the freshwater of what would become known as Battle Creek- the creek that runs diagonally through the Cypress Hills, from southeast to northwest; so-named because of the Cypress Hills Massacre, which took place in its valley the previous summer.

Cypress Hills to the South Saskatchewan River

Days 51-54

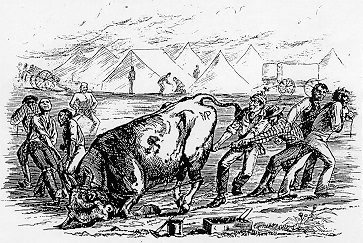

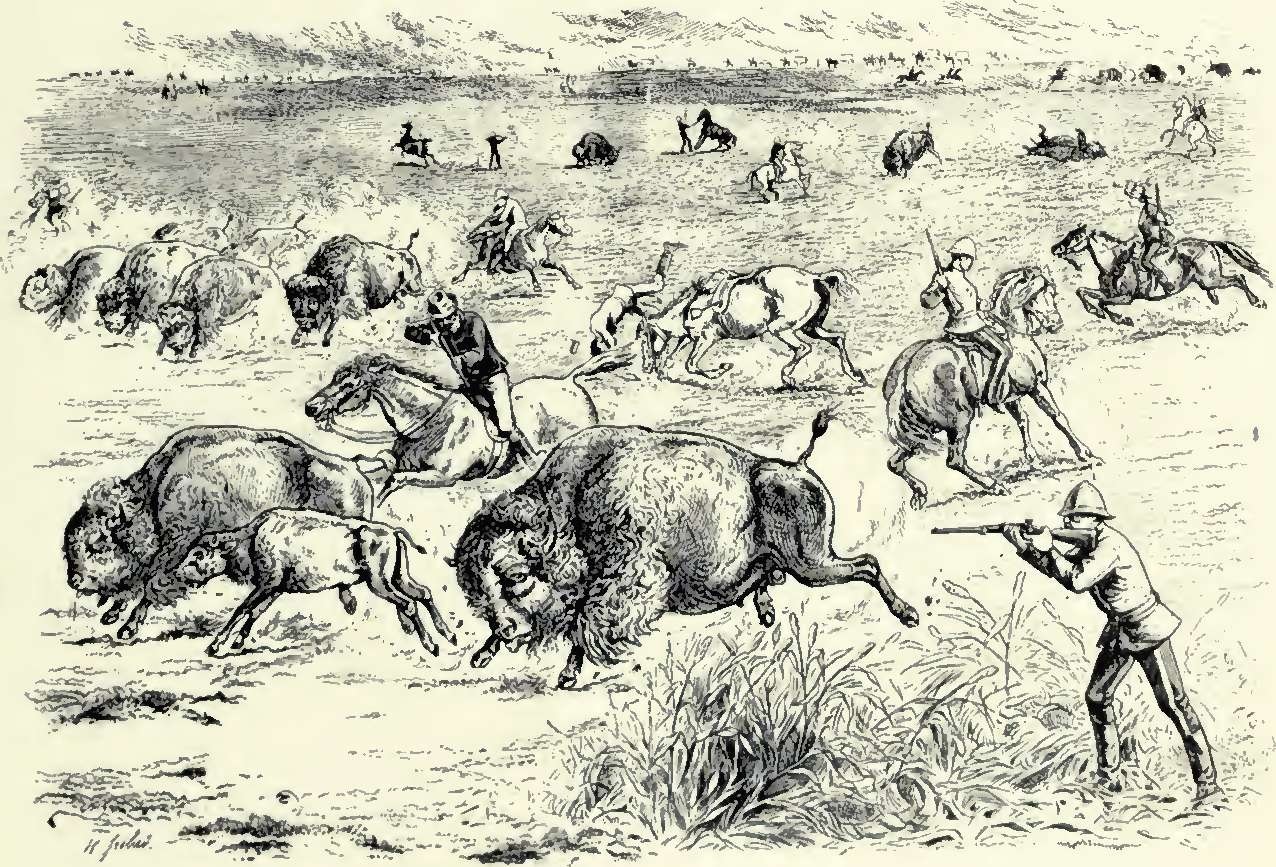

The North West Mounted Police took advantage of the shade, water and forage the Cypress Hills offered and stayed at the location for four more days. On the second day, August 27 (Day 51), several troopers, in their free time, crested a nearby hill and were rewarded with not only a magnificent panorama of the surrounding hills, but also an incredible prairie spectacle: a seething brown mass of buffalo that blanketed the prairie beyond as far as the eye could see. Surely few Mounties would have guessed that these massively prolific “kings of the prairie” would all but disappear from the Canadian Plains in five years. On their fifth day in the Cypress Hills (Day 54; Sunday, August 30), the Metis auxiliaries shot and dressed a couple of old buffalo bulls that ranged at the edge of the herd. According to some of the Mounties, their meat was almost too tough to eat.

Day 57

On September 2, 1874, while on the march, the Mounty officers tried their hand at buffalo hunting. Although the Mounties and their Metis guides managed to kill a number of animals, only the larger of the two buffalos that Commissioner French shot, a cow that yielded nearly 1000 pounds of meat, was dressed and roasted.

Day 59

On September 4, after a long day of riding, the Force made camp in a deep ravine. That afternoon, one of the sub-constables on guard duty spotted a glint of steel at the top of the coulee. No sooner did he raise the alarm than a Sioux scout, armed with a rifle, shambled down the coulee face and into the camp. The Indian was immediately brought to Commissioner French. Via an interpreter, the Indian, in broken French, told the Commissioner that the Sioux wanted the Mounties to leave. French replied that the Mounties were here to stay, and that they came to protect the interests of the “Great White Mother” (Queen Victoria) and all her “red children” in the Canadian west. In response, the Sioux- ostensibly one of a reconnaissance party of a much larger force- fired a shot into the air, and was quickly joined by six more braves. He then proceeded to tell Commissioner French that the Sioux had good reason to doubt the words of white men, but that they would, for the time being, accord the Red Coats the benefit of the doubt. After receiving gifts of tea, buffalo meat, ammunition and hardtack, the Sioux retreated up the coulee.

Day 61

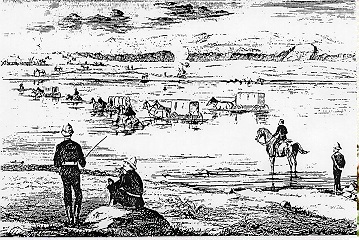

On September 6, Morisseau, the Metis scout from Fort Benton, rode back to the column with the announcement that he had found the Belly River. Commissioner French, who had a copy of an imprecise yet serviceable map from the Palliser Expedition, upon riding with Morriseau to the river’s edge, knew that the river was not the Belly River, but in fact the South Saskatchewan River. That evening, the force moved to the river and camped somewhere in the vicinity of present-day Medicine Hat.

Day 62

On the 62nd day, a small herd of buffalo intersected the column. The troopers, without permission from their officers, slaughtered as many of the animals as they could. That night, the Mounties had a feast.

South Saskatchewan River to Fort Whoop-Up

Day 67

On September 12, 1874, the Force, which had been travelling up the South Saskatchewan River, reached the confluence of the Bow and Belly Rivers, the head of the South Saskatchewan River, where Fort Whoop-Up, according to the report of Robertson-Ross, was supposed to be. Instead of a whisky fortification, the Mounties found three dilapidated wolfer shacks and Bow Island (the namesake of Bow Island, Alberta). Frustrated, Commissioner French decided that the Force would travel southwest and winter at the Sweetgrass Hills (the site of present-day Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, Alberta), while his self and a handful of officers would continue south to Fort Benton, Montana, to acquire directions.

Day 74

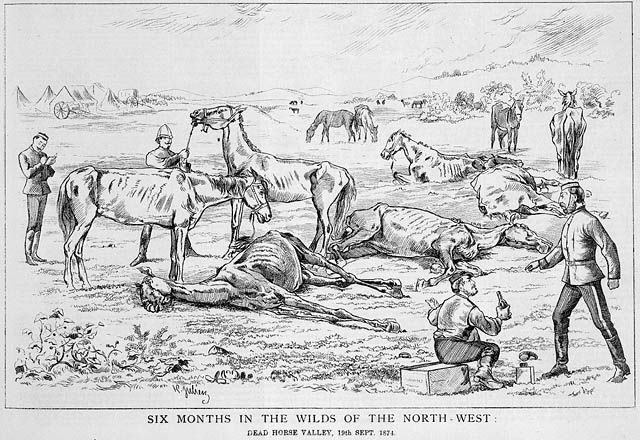

A number of horses died in the night. The Mounties named the coulee in which they died, “Dead Horse Valley.”

Day 76

On September 21, the Mounties arrived at the Sweet Grass Hills and camped at the base of the middle of the three buttes. There, Commissioner French split up the force, charging Inspector Carvell with leading Troops D and E south to the Boundary Commission Road, the Canadian-American trail that straddled the 49th Parallel, and then east down the road to Fort Ellice, Manitoba.

Days 79-90

On Wednesday, September 23, Commissioner French, Assistant Commissioner Macleod, Sub-Inspector Brisebois, Assistant Surgeon Nevitt, two constables, chief scout Pierre Leveille, and several Metis left the Sweet Grass Hills camp for Fort Benton, Montana. The small party, which had to stop for an 80 000-head buffalo herd, reached the so-called “Chicago of the Plains” in less than three days. Upon arriving at Fort Benton, French and Macleod sought out Isaac Baker and brothers Charles and William Conrad, three of the town’s most respected businessmen, all of them associated with the prosperous I.G. Baker Company. Unbeknownst to the officers, Baker was the founder, and the Conrad brothers were the current owners, of the notorious Fort Whoop-Up. The Mounties found the entrepreneurs with little difficulty and were promptly invited to dinner at William Conrad’s house. The businessmen, who had reluctantly entered into the whisky trade in 1871 to compete with their rival, Thomas Charles Power, knew that, with the arrival of the Red Coats, the illicit trade was doomed. Accordingly, they decided to forge a good relationship with the Mounties from the start in order to secure future business with them, and thus had no qualms about giving them the tools they needed to reach Fort Whoop-Up as timely as possible. Specifically, they recommended that the officers hire Jerry Potts, a half-breed renowned for his frontier prowess, as a scout. The Mounties followed the businessmen’s suggestion and hired Potts immediately. The following day, after purchasing supplies, the party split up. Commissioner French rode east to join officer Carvell and Troops D and E, en route to Fort Ellice, leaving Assistant Comissioner Macleod in charge of the majority of the Force. Macleod and the remaining party left Fort Benton and travelled north in the direction of the Sweet Grass Hills. They reached the main body of the North West Mounted Police on October 4.

Day 91

On Day 91, the Mounties left their camp at the Sweet Grass Hills and, guided by Jerry Potts, rode northwest to Fort Whoop-Up, actually located at the confluence of the Belly and St. Mary’s Rivers. That afternoon, they discovered the desiccated corpse of an Assiniboine brave, its scalp removed and its torso bristling with a surfeit of arrows- according to Potts, likely the product of whisky. At Macleod’s command, the troopers buried the body.

Day 94

On Friday, October 9, the North West Mounted Police finally reached the palisaded walls of Fort Whoop-Up. Atop one of the four corner bastions flew something resembling a Betsy-Ross-style American flag (according to some historians, the flag was Fort Whoop-Up’s unique trading banner, which the City of Lethbridge (present-day Lethbridge is located on the site of Fort Whoop-Up) would adopt years later). The Mounties, after training their heavy 9-pounder cannons on the fort, approached the gates and were greeted by current owner Dave Akers. They stated their purpose, specifically that they came to put an end to the whisky trade. Despite Akers’ protest that Whoop-Up had never sold whisky to Indians, the Mounties demanded permission to search the fort. The whisky trader had no choice but to comply. Akers had been forewarned of the Mounties’ coming, and had cached his contraband in the surrounding coulees. Accordingly, the Mounties found no evidence with which to condemn the fort, and so they left it after promising Akers they would return to establish a post within the fort. After the inspection, Jerry Potts led the Force a ways up the Belly River and suggested that the Mounties establish their post somewhere in the area. The Mounties took Potts’ advice and built their first permanent post on an island in the river. Upon Commissioner French’s later recommendation, the post was christened Fort Macleod in honour of Assistant Commissioner James Macleod. The Great March of the North West Mounted Police was over. The end of the whisky trade, and the establishment of law and order in the Canadian West was about to begin.

Source

- The Mounties March West- The Epic Trek and Early Adventures of the Mounted Police, 2004, Tony Holliha

Leave a Reply