Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XXII – After a Murderer.

Chapter XXIII

Trouble with the Indians at Calgary

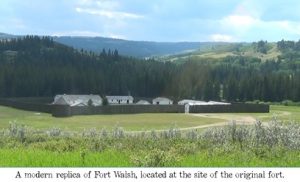

SHORTLY AFTER MY arrival at Fort Walsh, I obtained two months’ leave, to return to Fort Calgary, at which place I intended to take up a ranche on the bottom where the present town is now built, and I wished to make arrangements with an ex-policeman, an old servant of mine, Joe Butlin, to build a house before winter set in. As Colonel Macleod was returning to Fort Macleod himself, I took the opportunity of travelling with him, he having a four horse team and spring wagon. I was also able to take my baggage along, riding my troop horse. The Indian agent, Macleod’s son, Norman, was also with us, having just arrived via the Missouri from Canada, and was on his way to join his father at Fort Macleod. Jerry Potts, and two other men formed the balance of the party.

SHORTLY AFTER MY arrival at Fort Walsh, I obtained two months’ leave, to return to Fort Calgary, at which place I intended to take up a ranche on the bottom where the present town is now built, and I wished to make arrangements with an ex-policeman, an old servant of mine, Joe Butlin, to build a house before winter set in. As Colonel Macleod was returning to Fort Macleod himself, I took the opportunity of travelling with him, he having a four horse team and spring wagon. I was also able to take my baggage along, riding my troop horse. The Indian agent, Macleod’s son, Norman, was also with us, having just arrived via the Missouri from Canada, and was on his way to join his father at Fort Macleod. Jerry Potts, and two other men formed the balance of the party.

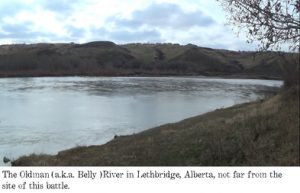

Our journey was uneventful until we came to the Belly river at Whoopup, where we found the stream very high, and just managed to cross without swimming. We dined here and went on to Slide Out, that being the second crossing of the same river. It was then about six in the evening, and Colonel Macleod having taken my horse, I rode in the wagon. He and Jerry crossed the river, and being on the ford they got over without swimming. I told the driver to drive in after him, but when we were nearly half way over, on the south bank, and come over in the morning, and that himself and Jerry Potts would go on to Macleod that night, nine miles north. We turned and went back, although I was loath to do so, having made a good start to cross. However, we had to obey orders, and went back.

Our journey was uneventful until we came to the Belly river at Whoopup, where we found the stream very high, and just managed to cross without swimming. We dined here and went on to Slide Out, that being the second crossing of the same river. It was then about six in the evening, and Colonel Macleod having taken my horse, I rode in the wagon. He and Jerry crossed the river, and being on the ford they got over without swimming. I told the driver to drive in after him, but when we were nearly half way over, on the south bank, and come over in the morning, and that himself and Jerry Potts would go on to Macleod that night, nine miles north. We turned and went back, although I was loath to do so, having made a good start to cross. However, we had to obey orders, and went back.

We put in a most unpleasant night. Having no tent we slept under the wagon. The mosquitoes were very bad all night, and sleep was almost impossible. During the night two of our horses crossed the river, although hobbled, and in the morning we could see them on the other side. A little after daylight I sent the driver, Hooley, over after them, and also instructed him to pay particular attention to the ford, so that he would know where to drive when we started over. He got across all right, and brought back the two horses. I watched him cross, and saw that the water was about breast high, and a swift current running. He informed me that he considered the ford all right and that we would have no trouble in getting over.

We therefore loaded the wagon and hitched up, and started for the river. There was a small log shanty on the north side, not far from the river bank, owned and occupied by two ex-policemen, Bell and Patterson, who had a short time before left the force, and taken up a ranche at this point, intending to go into farming and stock raising. These men were in the house at this time, but it being very early, they were still in bed. We had reached the middle of the river, which was about breast high on the horses, when the lead team baulked. It seems that they were sometimes given to this habit, although I was not aware of the fact. I took the reins of the leaders, and the driver held those of the wheel team, and after a short interval, we started them all together, and I handed back the reins I held to the driver. We had only gone a few steps when they stopped a second time, the leaders swerving down stream, dragging the wheel team round with them, and tilting over the wagon, throwing me out into the river among the horses. How I escaped being injured by them I cannot tell, but, half drowned, I managed to gain the shore, and scrambling up the bank, saw that young Macleod and Stewart had jumped off and swam ashore. The team and wagon were going down the centre of the river; the driver had let go of the reins, and was holding on to the side of the seat, the water being up to his waist. The horses were swimming, and the leaders having turned round, were frantically pawing on the team behind them. The driver, who had completely lost his presence of mind, called out, “Mr. Denny, come and help me!”

I of course jumped into the river, swam down towards the wagon, and had come within a few yards of it when it turned completely over, with the man underneath, and the whole, horses, man and wagon, disappeared. I swam over the spot, and down the river for a quarter of a mile, without any signs of any part coming to the surface, and being nearly exhausted, I had to make for shore.

In the meantime, the two young men had watched this horrid catastrophe from the bank, and being young, were naturally in a very nervous state. I called up Mr. Bell and Mr. Patterson, and, borrowing two horses from them, sent Macleod and Stewart into the fort for assistance. I, together with Mr. Bell and Mr. Patterson, went down the river and found that the wagon, with the drowned team still attached, had landed on a bar in the middle of the river, about half a mile down. Of poor Hooley there was no sign. We could do nothing until assistance arrived from Ft. Macleod, as there was no boat on the river. We waited about an hour and a half, when a party of men, with a boat loaded on a wagon, arrived, and we went out to the wreck, and after many hours’ hard work, managed to disentangle the horses, and bring the wagon and harness and some baggage ashore, but no sign whatever of Hooley’s body could be discovered. We then went many miles down the river, searching, without success, and towards evening reluctantly had to relinquish the search. Most of our baggage was lost, but, curious, as it may seem, not a thing belonging to Col. Macleod was missing, even his waistcoat that contained a gold watch, and had been left on the driver’s seat, was recovered. I lost, among other things, a good part of my uniform, together with three months’ pay I had in my uniform case.

Poor Hooley’s body was not recovered for nearly a month afterwards, when it was found about twelve miles down the river from where the accident happened, and was buried with military honors at Macleod. This was one of the many fatal accidents that occurred in those days in crossing the dangerous rivers in this country, and many more occurred in after years. These mountain streams are very dangerous, the current being so swift that the different bars are constantly changing, and where you found a good ford one year, you might be swimming the next.

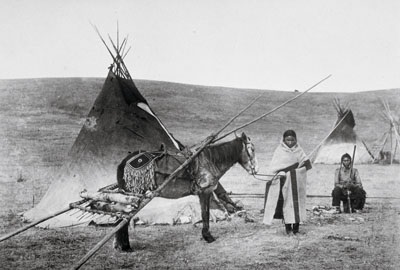

We found on arrival at Ft. Macleod that summer, that the Sarcee Indians, who were camped at Calgary, and very badly off for food, were making themselves very unpleasant to those in charge of the Hudson’s Bay Co., and I.G. Baker & Co’s stores at that place, and there being no police then stationed there, they had it pretty well their own way and we had not been long at Macleod before word was sent us from there, that the storekeepers were in danger of their lives, and asking for assistance. These Sarcee Indians, although a small tribe of only about 500 all told, were by far the most troublesome Indians in the west. They came originally from the far north, somewhere in the vicinity of Great Slave Lake, and their language was similar to that of the Chipewayans who still live in that section. This portion of the tribe must have migrated south very long ago, as they themselves have no record among them when this migration took place. They were at one time a large tribe of several thousands, but were continually at war with the Blackfeet and all other tribes of plain Indians, and this, together with the smallpox, which killed off hundreds, was the means of bringing the numbers down to what we found them on our arrival.

They had been given their reserve with the Blackfeet at the Blackfoot crossing, and were told that only at that place would they receive rations. They could not get along with the Blackfeet, and went in a body up to Calgary, to demand food, and when they found the place without police protection and the two stores there well provided with goods, they began to demand in a very threatening manner that they be supplied with all they required.

The Indian agent, Col. Norman Macleod, together with myself in charge of a police detachment of eight men, and Sgt. Lawder, a N.C. officer, therefore proceeded at once to Calgary to move the Sarcees away from that place, and to punish any who had committed depredations. There was not much lagging on the road, and we made Calgary on the second day, and right glad the few settlers at that place were to see us.

The Indians had, up to this time, gone no farther than threatening, and firing off their guns inside the stores. The agent held a council in the fort, and on the Sarcees refusing to go back to the Crossing, promised to issue them rations at Ft. Macleod, if they would go there, which they were very loath to do, wanting to be rationed at Calgary, but this was altogether out of the question, there being no cattle or other supplies at that place. The agent then left Calgary and proceeded to Morleyville to visit the Stoney Indians, leaving us the job of getting the Sarcees out of Calgary and on the road to Ft. Macleod.

We had very hard work for them; for three days they refused to move and even threatened us in the fort. We had to nearly all keep on guard day and night, as it looked very much as if they would attack us, and they no doubt would have done so had we not shown a bold front. We, as they say in this country, “bluffed” them off, and on the third day they promised to go the following morning, and asked help to move their tents and goods, as their horses were all very poor. This I promised them in the shape of carts, and also told them that if they did not move on the following morning, I would pull down their tents and take them off. This was a pretty bold threat, but we had to see it through. I therefore engaged Sam Livingstone, a rancher in that vicinity, and an old Hudson’s Bay Co. man, to bring a number of carts the next day to take them south. On the following morning I went to the camp with all the men I could collect, (I think ere were thirteen of us,) and found no sign of any move on the part of the Indians. I therefore drew up the men with their rifles loaded, just on the outskirts of the camp, and I and Sgt. Lawder commenced to pull down the tents. The Indians swarmed out and were very nasty for a time, but cooled down at the sight of the

armed party outside the camp, and presently began to pack up their goods into the carts we had handy. One shot was fired from the back of a lodge that was still standing, and the bullet came unpleasantly close to Sgt. Lawder. We could not ascertain who fired the shot, and as the Indians were well under way in their moving, we paid no more attention to it. We got them well on the road south by the afternoon, stayed with them for one day, and then rode on to Ft. Macleod. The camp arrived at that place in four days, and for the next year remained there drawing rations, after which time they had a separate reserve given them on Fish creek, about ten miles from Calgary, where they have remained to the present day.

A sad death, and one that cast a gloom over us for a long time, occurred this fall. Capt Clarke, the adjutant of the force, and a great favorite with all ranks, died at Ft. Walsh of gastric fever. This was always an unhealthy post and a good many men died there of fever during the few years it was occupied. Capt Clarke was the first officer we had lost since we came to the country, and his death was greatly felt by all. Dr. Kittson and Dr. Kennedy, our two police surgeons, and both very clever men, attended him with all that skill could accomplish, but he died in spite of all, and was buried at Ft. Walsh. The monument over his grave was still standing a year or two ago, although the fort itself and all the builders of the old village have long since disappeared most of them having been burned down by Indians some years after it was abandoned.

Continued in Chapter 24: Indian Farm Started.

Leave a Reply