Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XXI – Famine Among the Blackfeet.

Chapter XXII

After a Murderer

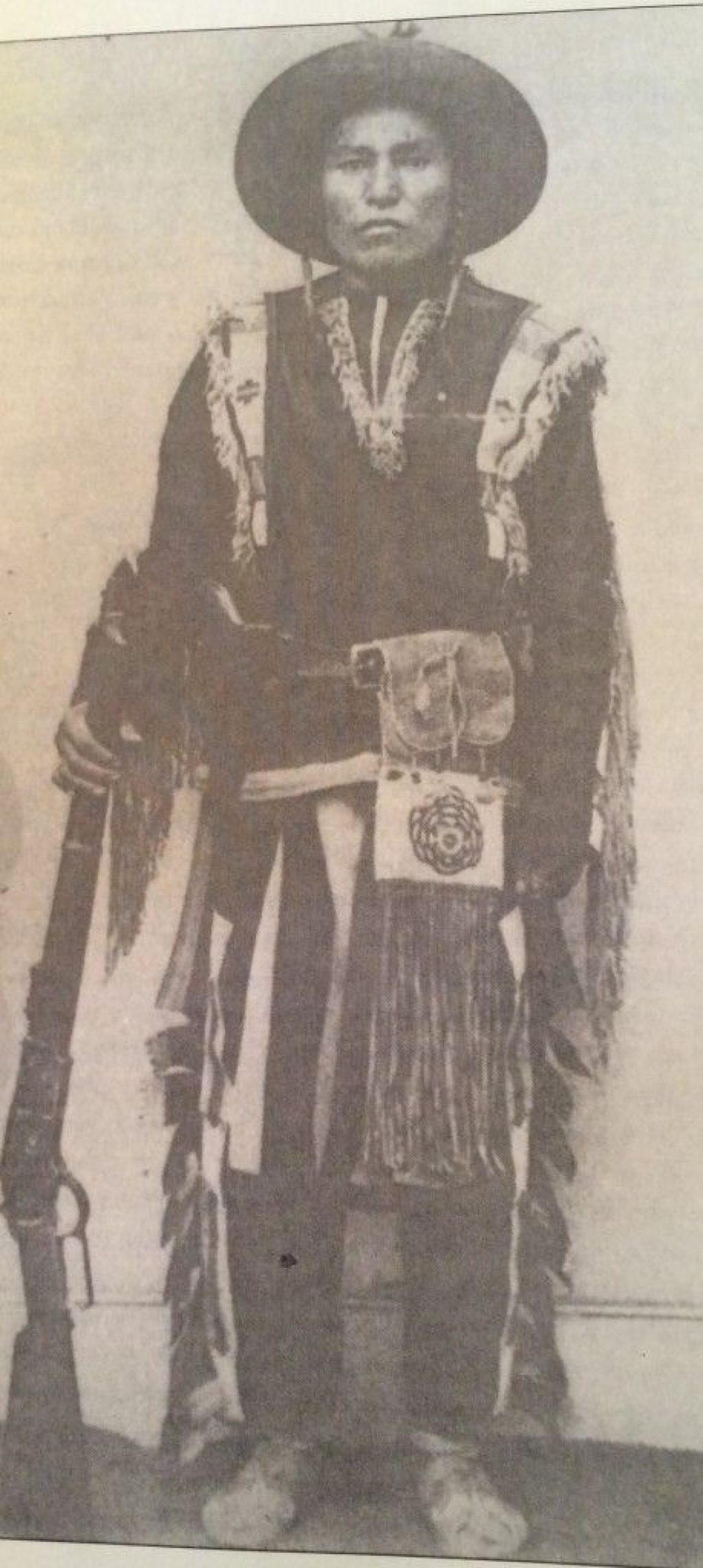

WE RECEIVED WORD during the winter of 1879 at Fort Walsh that the Indian, Star Child, on whom suspicion rested as having been the murderer of Greybourn, was in an Indian camp south of Fort Benton, Montana, and Major Crozier who was in command of Fort Walsh that winter, instructed me in the early spring to proceed to Benton, and try indirectly, with the sheriff of Fort Benton, to have the Indian given over to us. I was authorized to offer as high as $500 to attain that object. Colonel Macleod was that winter at Fort Macleod, which place was for the time being headquarters of the force, on account of the disturbed state of the Indians in that district. An Indian agent had been appointed during the winter for Treaty No. 7, with headquarters at Fort Macleod, and the commissioner’s brother, Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Macleod, was the one appointed. He was expected to arrive in Benton in the spring, and the commissioner was to be there to meet him. Commissioner Macleod had the previous year brought his family out west, and his wife, with the exception of Mrs. Winder, and the wives of two of our officers who came out in the same year, 1877, but a few months earlier, was the first white lady in the Fort Macleod district of the North West. These ladies attended the treaty in 1877, and shewed the greatest courage and cheerfulness through all the hardships and dangers they had to encounter, through long and rough journeys with poor transport, and living in mud-roofed huts; through which the water streamed during the rainy season. They were often left alone with only the company of each other, while their husbands were away on duty, sometimes for long intervals, and this in a country only inhabited by thousands of warlike Indians, and a white population not the most select.

WE RECEIVED WORD during the winter of 1879 at Fort Walsh that the Indian, Star Child, on whom suspicion rested as having been the murderer of Greybourn, was in an Indian camp south of Fort Benton, Montana, and Major Crozier who was in command of Fort Walsh that winter, instructed me in the early spring to proceed to Benton, and try indirectly, with the sheriff of Fort Benton, to have the Indian given over to us. I was authorized to offer as high as $500 to attain that object. Colonel Macleod was that winter at Fort Macleod, which place was for the time being headquarters of the force, on account of the disturbed state of the Indians in that district. An Indian agent had been appointed during the winter for Treaty No. 7, with headquarters at Fort Macleod, and the commissioner’s brother, Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Macleod, was the one appointed. He was expected to arrive in Benton in the spring, and the commissioner was to be there to meet him. Commissioner Macleod had the previous year brought his family out west, and his wife, with the exception of Mrs. Winder, and the wives of two of our officers who came out in the same year, 1877, but a few months earlier, was the first white lady in the Fort Macleod district of the North West. These ladies attended the treaty in 1877, and shewed the greatest courage and cheerfulness through all the hardships and dangers they had to encounter, through long and rough journeys with poor transport, and living in mud-roofed huts; through which the water streamed during the rainy season. They were often left alone with only the company of each other, while their husbands were away on duty, sometimes for long intervals, and this in a country only inhabited by thousands of warlike Indians, and a white population not the most select.

I rode to Fort Benton, about 150 miles from Fort Walsh, in the early spring of 1880, and tried to make arrangements to have Star Child turned over to us. Extradition was out of the question, as our evidence was very slight, and I endeavored by the offer of a reward to have this Indian captured, but the terms asked were out of my power to give, according to the instructions I had received. I, therefore, waited for the arrival of Colonel Macleod, who came in after I had been in Fort Benton a few days, with Jerry Potts, our guide, Sub-Inspector Neal, who was on his way to Ottawa, and Staff-Sergt. Norman, the commissioner’s secretary. We remained in Benton for five weeks, waiting the arrival of Col. Norman Macleod, the new Indian agent who was coming by way of the Union Pacific, and from there by stage to Helena and Benton. This was my first visit to Fort Benton, and of course I had to “take in the town.” At that time Benton was quite a busy western town of about 1,000 inhabitants. It is the head of the navigation of the Missouri River, and for fifty years back had been a great Indian trading post. The old fort, built of unbaked bricks, or “adobies,” as they were termed, still stood, although some handsome business blocks and residences were to be found in the town. It was a very rough place. Gambling and dance houses, together with liquor saloons, occupied the whole of Water street, facing the river, and the sidewalks and streets were a mass of playing cards, thrown out from the different gambling places as the easiest way to get rid of them after use. Mr. C. Conrad, of the firm of I.G. Baker and Co., who had spent the first two years at Fort Macleod when we first came out, showed us the greatest hospitality, placing his very comfortable house at our disposal. They boasted of a club in Benton at that time, the Choteau, called after the name of the county, and our names were immediately enrolled as members. We found it to consist of a very mixed array of members, among whom we met Colonel Donnelly of Fenian memory, who was a justice of the peace, practicing law in Benton, and not at all a bad fellow socially. He seldom referred to the little unpleasantness that existed between himself and the Canadian Government. We also met the colonel and officers of the portion of the Seventh United States Infantry stationed at Fort Benton, the headquarters of the regiment being at Fort Shaw about 10 miles west of Benton. As it was, we spent a very pleasant time in Benton, and were quite sorry to say good-bye on the arrival of Mr. E. Galt, our assistant Indian commissioner, and Colonel Norman Macleod, Indian agent.

Colonel Macleod, the commissioner, together with his brother, proceeded to Fort Macleod, with the guide Jerry Potts. Mr. Galt and I went to Fort Walsh, as Mr. Galt, as assistant Indian commissioner, was on a tour of inspection of the western Indian reservations comprised in Treaty No. 7. Colonel Macleod’s trip was an uneventful one, with the exception that in crossing the St. Mary’s river, the stream being high and the ford rough, Staff-Sergt. Norman, who had acted as Colonel Macleod’s secretary for some years, and who was sitting in the rear seat of the wagon, was thrown into the river, and by hard swimming reached shore without anyone being the wiser, with the exception of Jerry Potts, who was sitting beside him. Shortly before reaching the farther shore, Col. Macleod noticed a woolen cap floating down the river, and turning to the driver said: |Hold up, I think Jerry has fallen in.”

Jerry, sitting behind and hearing this, became most indignant, and answered back, “No, sir, not by a d—-d sight, but your d—-d sergeant is drowned.”

However, Sergt. Norman was found none the worse, and no further accidents happened on the journey, and on arriving at Fort Macleod everything was found to be going on well. After a few weeks’ stay at that place, the commissioner proceeded to Fort Walsh, which then was the headquarters of the force.

I proceeded with Mr. Galt, assistant Indian commissioner, to Fort Walsh, where he inspected the different Indian camps in that vicinity. I then accompanied him to Fort Macleod, making a five-days’ trip of it, as the weather was cold and stormy. We met Colonel Macleod on the road, on his way to Fort Walsh. Mr. Galt and myself visited the Indians at Macleod and Calgary, Colonel Norman Macleod going with us, and taking over the duties of Indian agent of Treaty No. 7, his headquarters being at fort Macleod. A farm instructor and issuer of rations was stationed with the Blackfeet at the Blackfoot Crossing; one at Calgary for the Sarcees, and another at Morleyville for the Stonies. Instructors were also placed on the Piegan reservations, twelve miles above Macleod, and on the Blood reserve, south of the Belly river.

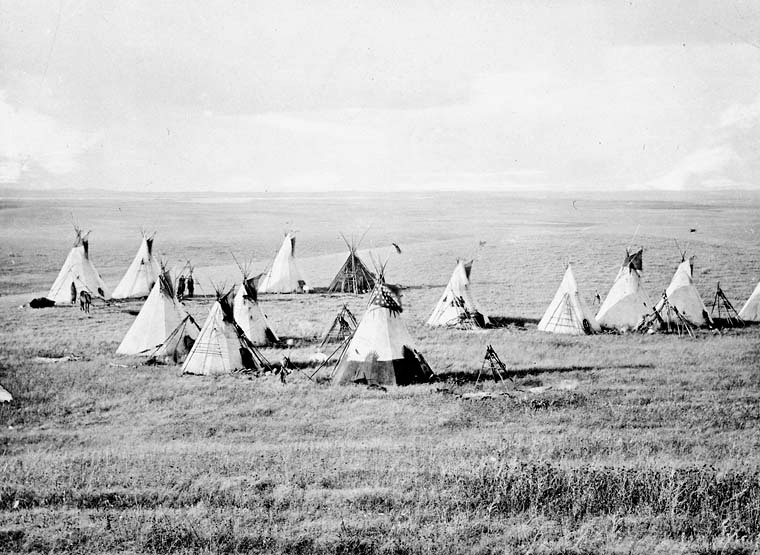

I remained at Calgary that summer with only ten men and a non-commissioned officer. It was necessary that some force should be stationed at this point, as a good many Blackfeet were camped at the Crossing, and there was also a large camp of Crees in that vicinity, and the two did not agree at all. In fact, at one time open collision between them nearly took place. Word was brought to Calgary that a Cree Indian had been killed by a Blackfoot at the Crossing, and that the Crees were about to avenge his death, and attack the Blackfoot camp. I, therefore, started for that point with what men I could spare, only six all told, with an interpreter, and made the ride to the Crossing in one day, arriving there late at night. We took a light wagon with us, but very little bedding. Some of the men were recruits, who had only come up that year, and the ride tried them severely. It was as much as I could do to get them in that night. We camped on the river bottom until morning, when we found a Blackfeet camp of about 1,000 Indians on the edge of the bluff overlooking the river, and the Cree camp, nearly equal in numbers about three miles distant. Many of the Blackfeet chiefs came down to see me. They had many complaints against the Crees, and on my asking if it was true that a Cree had been killed, they informed me that it was so, but they had lots of excuses. I demanded the Indian, but found that he had left the camp and gone no one knew where the day after the killing was done. I then told the Blackfeet to put up a large lodge in their camp, and that I would go to the Cree camp, and try to get their chiefs to come over and meet the Blackfeet, and try and make peace between them. This they promised to do, and also to talk reasonably and do their best to straighten matters.

I rode with the interpreter to the Cree camp, and found them more amenable to reason than I expected. In fact, they were pretty badly scared, as being in the Blackfoot country, and a long way from any of their friends, they were very much at their mercy. However, they felt pretty sore over the killing of one of them, but were willing to overlook it if the Blackfeet would pay them, and agreed to come over on the following day and make peace with them, after which they promised to move camp and go back to the Cypress Hills, and join the rest of their tribe. On my return to camp, I informed the Blackfeet of this, and they were satisfied. I found that some of the Indians had brought dried meat to our camp, and had pitched a lodge for us, as we had no tent with us. This showed great friendliness on their part, and the meat was most welcome, as we had only bacon with us.

The following morning I and the interpreter went to the Blackfoot camp, and were shown the tent they had pitched for the Council. The two of us seated ourselves alone at the head of it. After a short interval the head chief, Crowfoot, arrived, and with great ceremony paced round the fire, and shook hands with me, at the same time throwing down before me a fine head and tail buffalo robe. I told the interpreter to tell him that I had not come to take presents, but to settle the trouble between them and the Crees. The interpreter advised me to take the robe, as it was given to show that they were friendly towards us, and that if I did not do so, the Indians would think that we were not friendly to them. I, therefore, threw the robe behind me, and after doing so, thirty-three chiefs, both Crees and Blackfeet, filed in and shook hands, and each chief threw down a robe. After having taken the first, I now had to take all, as had I taken the one and refused the rest, they would have been deeply affronted. I, therefore, had thirty-four robes piled up behind me. However, these robes came in most usefully, as we all were short of bedding, and the cold weather was coming on before we got back to Calgary. I divided them equally among the men, who were delighted to get them.

After a solemn smoke all round, I advised the Crees to move, and also the Blackfeet to settle with the family of the Indian killed in the usual Indian fashion, by paying so many horses, and altogether gave them lots of advice. I had, however, to sit for several hours and hear the different grievances they had against each other, and sometimes the talk waxed pretty hot. However, I managed to settle their troubles, and the Crees promised to move the following day and the Blackfeet to give up the murderer should he come into camp. I made them shake hands all round and, after seeing the Crees out of camp, returned pretty well done up to our camp, near the river. We remained here for two days until the Cree camp was well started on its way to the east. We then pulled out for Calgary, being two days on the road, with very cold stormy weather all the way. But for a little management there might have been most serious trouble between these two large camps, and had it once started, it would have spread to other camps, and a general Indian war between the Crees and Blackfeet would have followed, which, with our small force, would have been nearly impossible to quell. Our hands were pretty full all this summer, the Indians being very restless, and being unaccustomed to remaining for any length of time at one place, it was difficult to keep them on their reserves, where they could receive their rations.

Although the buffalo were in vast herds when we arrived in 1874, they must in the olden days have been many times more numerous. There are, at the foot of a bank of about fifty feet in height, on the Elbow river, six miles south of Calgary, the remains of many thousand animals, which must at one time have been driven over this bank. Below the soil at the foot of the cliff there is a thickness of at least three feet of nothing but old bones, pressed by the weight of the soil into a solid mass. How far back this extends, it is impossible to say, but ages ago an enormous number of buffalo were in some manner slaughtered there. I have found flint arrow heads mixed among these bones, which shows that the Indians had a hand in the slaughter.

I returned to Fort Walsh in the early part of the summer of 1880, leaving one man in charge at Calgary, and he, with the exception of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trader, A. Fraser, and G.C. King, who had charge of a small trading store belonging to I.G. Baker, was the only white man left at Calgary.

At Fort Macleod things were about the same. A few more settlers had taken up ranches along the Old Man’s river, being principally old policemen who had taken their discharge in the country and having saved a little money, had invested in a few head of stock and settled down. Most of these early pioneers did well and many of them are still in the country and well off.

The Indians in the vicinity of Macleod now and then killed cattle but, horse stealing was their principal pastime. This we found was impossible to put a stop to, and the guardroom was generally pretty well filled up with these Indian horse thieves.

Jingling Bells, the Blackfoot Indian who killed the Cree at the Crossing in the spring, was captured this summer and after being in the guardroom at Macleod for a month, made a desperate break for liberty, and after swimming the river, with a volley fired after him by the guard, managed to effect his escape. He was again captured about two years afterwards and sent to the Manitoba penitentiary, where he died, after being in jail only one year.

Star Child, the Indian supposed to have killed Constable Greybourn, was captured after considerable resistance in a Blood camp. He was tried by Colonel Macleod in the fort and although there was little or no doubt that he was the man who committed the murder, there was no proof whatever to convict him, and he was therefore released. He was arrested about a year afterwards, and sentenced to give years in the penitentiary for horse stealing, and he also died in prison before his time had expired. This was the case with nearly all the Indians sent down; they very rarely lived any length of time in confinement, consumption carrying them off in nearly every case.

The village of Macleod had not increased at all, but still a good deal of money was in circulation and there was plenty of work. Mr. C. Conrad had returned to Fort Benton, and Mr. D.W. Davis was in charge of I.G. Baker & Company’s business at Macleod.

From time to time a whisky trader was arrested and fined or imprisoned, but whisky could nearly always be procured, (a vile compound at $5 per pint bottle) but the popular beverage was Jamaica ginger or alcohol with a little essence of ginger, at $1 a six-ounce vial.

From time to time a whisky trader was arrested and fined or imprisoned, but whisky could nearly always be procured, (a vile compound at $5 per pint bottle) but the popular beverage was Jamaica ginger or alcohol with a little essence of ginger, at $1 a six-ounce vial.

It was seldom that an Indian could now procure liquor, and the whisky illegally smuggled in was sold altogether to the whites. The permit system had now come into force. A permit was granted by the lieutenant-governor to any party well recommended, for not more than two and a half gallons of liquor, said to be for medical purposes. These permits were unfortunately transferable and the system was thereby abused.

At Fort Walsh things were more serious than in the west. Indians of all tribes were congregated in its vicinity and endless trips into the camps had to be made, and the greatest judgement had to be shown in making arrests, as the Indians, particularly the Crees, showed a sullen and unfriendly attitude towards us. They were at this time half starving, little or no rations being issued them by the Indian department at Fort Walsh, so the burden of all was laid on the shoulders of the brave little band of police, under Assistant Commissioner Irvine at that post.

Continual journeys had to be made to Wood mountain, near which post the Sioux in large numbers still camped, causing ceaseless anxiety to the police. Some remarkably fast journeys were made by the assistant commissioner to this post, through a country devoid of wood and game for one hundred and seventy-five miles. Up to my arrival there in the summer of 1880 from Calgary no trouble had occurred, but the work done was remarkable, and the steadiness and forbearance of the men beyond all praise.

Continued in Chapter 23- Trouble with the Indians at Calgary.

Leave a Reply