Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XIII – Journey to Red Deer.

Chapter XIV

Building the Village of Calgary

AFTER WE HAD SETTLED in the camp a few days we were visited by a Catholic priest who had been living for some months in a log hut some thirty miles up the Elbow river. He had seen no one for three months except a young Indian boy he had living with him, and was half starved, not having had any substantial food for a long time. It did us good to get a square meal into him and watch the gusto with which he ate it. He had only been a few months in the country from France, and had been sent south to learn the Blackfeet language, among which Indians he was to remain as a missionary. Father Ducet was not long in acquiring the language, and in a few years was a useful missionary among the plain Indians.

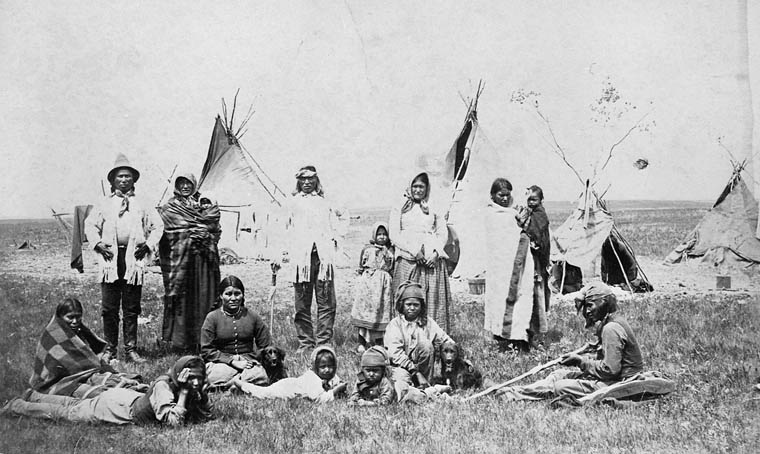

We were visited by Mr. McDougall of Morleyville, who held service at our camp every other Sunday. A few camps of Indians now and then came in to visit us. All were very friendly and well off for food and clothing with large bands of horses in their camps. We found an old Indian death lodge standing on the bank of the river containing the bones of some three or four Indians who had been killed the previous summer in a fight with some whisky traders from the south. Their remains were scattered about the tent and outside, having been eaten and dragged out by wolves. It was the habit of the Indians in those days when buffalo skin tents were plentiful and only used for one year, to leave their dead in lodges, covered with robes, blankets or other articles supposed to be of use to them after death, when they went to the Sand hills. The Indians supposed that their people after death went to the great Sand hills on the South Saskatchewan river and there hunted mice instead of buffalo. I have often had Indians stop in the Sand hills near the Blackfoot crossing, gravely showing me the track of mice in the sand, and assure me that some of their dead friends were hunting them. A few years before we came to the country the Indians were in the habit of killing a horse or two when any chief or Indian died, so that they should have their riding animals with them in the Sand hills.

We also found the remains of a white man who had been killed and buried by his trader friends some seven miles up the Elbow, at which place a trading post had stood some two years before with a party of whisky traders living in it. They had been attacked by Blackfeet their horses run off and one of their number killed and several wounded. Mr. Davis who was trading whisky a few miles above, had loaned them horses and they had all gone south. The Indians sacked the stores and burnt them to the ground. They buried their comrade, but we found that wolves had dug him up and we reburied what remained of him.

I.G. Baker’s men arrived a few days after we went into camp and proceeded up the river to cut dry pine logs, fourteen feet long to build the fort. They found all the timber they required about six miles up the Elbow from the mouth, and building a boom, a little above the mouth, soon had all the logs they required driven down the river.

Mr. Davis had been engaged and placed in charge of the party and it did not take them long to put up a picket fort to accommodate fifty men and stables for about the same number of horses. The buildings were covered in with earth and between the logs, closed with clay, all being surrounded with a loge stockade about ten feet high and the buildings facing inwards round a good-sized square. Lumber for doors and flooring was cut with a whip saw, by half breeds, many of whom had camped in the vicinity.

Our buildings were ready for occupation before Christmas and good fire places had been built in most of the rooms out of good building stone found on the rivers. Firewood was plentiful and a party of men went up the river and drove enough of it down to last all the winter. Baker’s men had also built a good substantial store and a couple of dwelling houses, and it was not long before they had it stocked with a good assortment of all kinds of trading goods with Mr. Davis in charge and an ex-police sergeant as clerk.

A billiard table was also put in by an enterprising ex-whiskey trader, and cider, made from raisins, sold at 25 cts per glass. This establishment coined money for some years and I.G. Baker’s store made a fortune with their white and Indian trade. In 1876 as many as 15,000 buffalo robes were shipped south by this store alone, costing them in trade about fifty cents each and fetching in Benton from five to ten dollars according to the quality.

The Hudson’s Bay Co. moved down one of the buildings from Ghost river, and adding to it, soon had up a good trading store and dwelling house, and did a fair share of the trade for some years.

Contracts were given for hay, which was cut as late as October, and although not of the best quality, answered the purpose well. The grass in that section and all over the plains in the Northwest cures standing, with all the strength in it, thereby making the Northwest plains such a rich grazing ground both winter and summer for cattle and horses.

We were settled in the new fort about the beginning of December and were glad to get under shelter as the weather was pretty cold by that time. I made a trip to Ft. Macleod before the fort was finished and found things going on well there, much good work having been done and the whisky trade pretty well stamped out as a regular business. The guard room was full of prisoners, Indian and white, some serving a short term in the country and others to be sent down to the penitentiary in Winnipeg the following spring. Many new buildings had been erected at Macleod, which was by that time a good roomy fort, although built of cotton wood logs, which make the poorest of building material. This was unavoidable, as pine timber could only be procured some thirty miles up the river as we arrived so late in the season, and the horses were in such poor condition, we had to take the first timber available, which was the cotton wood on the river bottoms.

I returned to Calgary on Christmas night and found the troop spending the evening in old Christmas style, a Christmas dinner being given by the non-commissioned officers and men, to which most of the civilians at Calgary were invited.

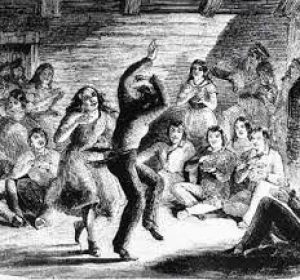

A pleasant evening was spent, the first Christmas ever celebrated at Calgary. The previous evening a dance had been held at the billiard hall, built that fall. The ladies consisted of the half breed belles who turned out in numbers well dressed, and some not at all bad looking. A jolly time was had, and some of those old time dances, held at Macleod and Calgary the first few years the police came in, went far ahead for fun and good hearty exercise, of any of the prim and select affairs held since the country has come to be settled.

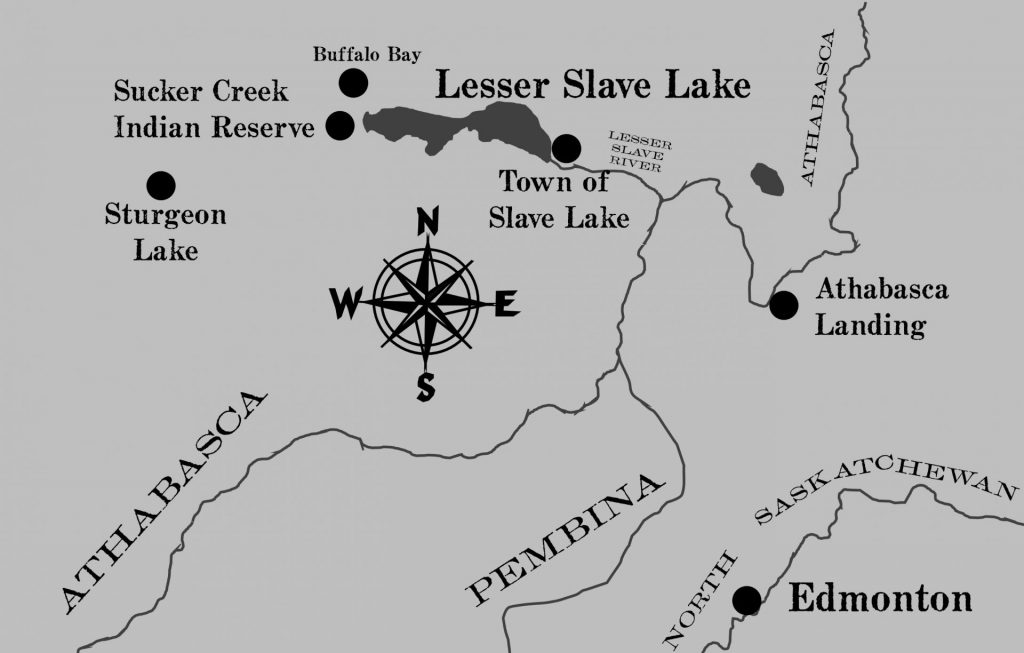

During the winter of 1875-6, I was instructed to proceed to Ft. Edmonton with money for the payment of the troops stationed there, they only having received pay at irregular intervals since they arrived at Edmonton in the fall of 1874. I took a guide and one man with me, and as the snow was deep and no doubt much deeper in the north, I took a flat sleigh, with a sort of bag made of raw hide in which I could sit and drive, with the provisions consisting of pemmican, biscuits, tea and sugar together with oats, securely lashed behind. This conveyance is easily drawn over the snow either by dogs or one horse, and 30 or 35 miles can be made in a day, a man riding ahead and beating a trail.

We had to do without a tent, and the first two days, until we struck the timber line sixty miles north, were pretty rough. We had to camp without wood with very cold weather for two nights. In reaching the timber, which continued to Edmonton, though we found the snow deeper, we always made a good camp and had roaring fires, which made the camping bearable. The distance from Calgary to Edmonton is about 200 miles which we made in six days and rather enjoyed the trip. We met with plenty of deer, two of which we killed. We crossed the Red Deer river on the ice and met a camp of Crees on a hunting trip and spent a night in their tents. They gave us a tea dance to celebrate the occasion, the principal feature of which consisted in the custom they had of a woman stepping from the dance up to whatever man she had picked and kissing him. He had then to make her a present. If an Indian, he would strip himself of his robe or blanket and throw it round her; if a stranger, they generally made a good thing of it. It was one of the Indians’ chances of levying toll on the unsuspicious strangers.

We arrived at the Saskatchewan river on the sixth day and crossed it on the ice. Ft. Edmonton is built on the north side of the river, on top of the bank overlooking the river, some 200 feet above the river bed. It is a very old H.B. Co. fort, probably 100 years old, with numbers of log buildings, all surrounded by a high log stockade with strong bastions at two of the corners. Many an Indian fight had occurred outside the walls. Often trading parties of Blackfeet or Bloods from the south would be met by parties of Crees at this point and bloody fights always took place. The gates of the fort would then be closed and the Indians were left to fight it out on the outside, trading goods or whisky being passed out to them through a wicket in the gate. However the Hudson’s Bay company had given up the sale of liquor some years before the police arrived and no collision had taken place between the Indians since.

Col. Jarvis with a troop of some forty men was living at this fort which was in charge of Mr. B. Hardisty, a chief factor and a life long employee of the company. In the summer of 1876 Col. Jarvis moved down the Saskatchewan river some twenty-seven miles and built a police fort on the south side of the river which was named Ft. Saskatchewan, and is today the head quarters of the police in that district. I remained a few days at Edmonton, my visit with money for the troops being much appreciated, as they had been without pay for a long time. The old fort was quite a curiosity to go over, only a portion of it being inhabited and even then quite a little village was collected within the walls. Many dog trains had come in during the winter loaded with fur from the northern forts as far north as the Athabasca river. These trains would return loaded with provisions and trading goods.

At that time all the fur from the far north along the Great Slave and Great Bear lakes and the Mackenzie river, came into Carleton, some hundreds of miles down the Saskatchewan river, and from there was taken overland to Winnipeg, and it was not until some three years after this time that the company put two steamers on the river, which landed goods at Edmonton, and from that time most of the far northern trade came via the Athabasca landing to Edmonton. I remained a few days at Edmonton and after a cold stormy trip returned to Calgary, the account of which I give in another chapter.

We had some trips after whisky traders during the winter, which passed off quietly. The game along the rivers and the buffalo on the prairies gave us an abundance of fresh meat. There were no cattle in the country that year, with the exception of a few cows brought in near Macleod from the south by intending settlers, and these did not amount to fifty head. It was not until some years afterwards that any number of cattle were brought in, and the country was found to be a good stock country. One herd of cattle was brought through a pass in the mountains west of Ft. Macleod named the Crow’s nest, by a man from southern Montana. He made a successful drive and found the pass a first-class one for driving stock through. It no doubt is one of the lowest and easiest passes in the mountains, with not nearly such heavy grades as that through which the Canadian Pacific railroad passes.

The herd of cattle wintered near Calgary, and before a year the owner had sold them at a great profit, and returned the way he came to Montana.

Fort Edmonton must have been built over 100 years ago, and had always been the head trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company along the Saskatchewan. It was visited by all the tribes of Indians from the south, it being in those days the only trading post in the west, and was the scene of many fierce fights between rival tribes of Indians. The plain Indians, such as the Blackfeet, always were at war with the northern or wood Indians, among whom were the Crees. When these parties happened to come to trade at the same time, they were not allowed inside the fort, but a wicket was opened in the wall, and the furs taken, and whisky or trading goods handed out. The Hudson’s Bay company was always careful to have nothing to do with any tribal matters among the Indians, particular their wars among themselves, and so kept good friends with all the different tribes with whom they traded.

The profits of the company in the old days were something enormous, as a glass of rum was their price for a beaver skin, and in the same proportion with everything they traded. A silver fox skin would be bought for a few yards of tobacco, which was put up in rolls of the old pig tail, and a handful of tea or sugar. They had the monopoly of the Indian trade in the west to within a few years before the police arrived, when some of the American traders had found their way into the country. But they traded principally whisky, and confined their trade to plain Indians, none going farther north than the Red Deer river, which was about 250 miles from the American boundary, and a hundred miles from Edmonton.

Our return trip from Edmonton, mentioned in the last chapter, was a cold and stormy one, the snow being very deep, and after we left the timber and reached the plains, our dried meat gave out, and we had to kill a buffalo to supply ourselves with meat; but the camping at night in the snow was the worst, as continuous watch had to be kept over the horses, and the cold was too great for sleep, it being 40 degrees below zero.

We arrived at Calgary after a six days’ hard journey from Edmonton, and glad enough we were to be once more inside the fort, with good blazing log fires, and something better than frozen meat to cheer us.

The winter of 1875-76 was a very cold one, and we had to make a good many trips during some of the coldest weather after whisky traders, some of whom were captured. On one or two occasions camps of Indians were found drunk, and then we had our hands full to avoid coming into collision with them. It was wonderful how well the work was done with so few men, not one instance occurring where any difficulty was experienced in making arrests among them.

During this winter a Methodist missionary among the Stoney Indians, whose camp was about thirty miles west of Calgary, was frozen to death. He and two sons were on a buffalo hunting trip out on the prairie some distance from any wood, and after cutting up and skinning some animals they had killed, they returned separately to their camp, which was some miles off. All arrived safely except the father, Mr. G. McDougal. A heavy snow storm prevailed at the time, and the weather was very cold. The two sons came into Calgary for help to search for their father, and for some days parties were scouring the country without success. The horse he was riding came into camp on the second day without the river; it was then known that there was no help for the lost man.

His body was found about a week afterwards, some miles from the camp. He had lain down from exhaustion, and was soon overcome by the cold. The body had been partly mutilated by wolves. This was the first death since our arrival at Calgary, and cast a shadow over our New Year.

I had a very narrow escape while looking for Mr. McDougal. The weather had turned quite mild, and I and Mr. Bunn, who was in charge of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post at Calgary, rode up the river one afternoon, in the hopes of coming across the lost man’s horse. The weather was so mild that we neglected to take overcoats, or to wear moccasins, which are absolutely necessary in cold weather. We rode some ten miles up the river, when one of those sudden changes occurred that are peculiar to this country in the winter. From clear sunshine and a soft wind, the wind suddenly changed to the north, very cold, and a snowstorm, or blizzard, set in in a few minutes. We rode for our lives, struck the river a mile or so above it, but luckily recognized the locality; we arrived at the fort nearly frozen. A very short time longer, and my feet would probably have been frozen, as my boots were frozen solid, and it was a long time, though keeping my feet in the snow, before I regained feeling in them.

The following spring we had plenty of work among the Indians, as although they had patched up a temporary peace with their enemies the Crees, they would steal horses from each other, and now and then one would be killed, and to watch the movements of the different bands scattered along the Bow and Red Deer rivers kept us fully occupied. On several occasions I had to go down to a point on the Bow river, named Blackfoot crossing, some sixty miles below Calgary. This was an old camping and burial spot of the Blackfeet from time immemorial. There was also a good ford on the Bow river at that point, whereby it derived its name of the Blackfoot crossing, or the “Ridge under Water.” The Blackfeet venerated this point, as for years unnumbered their dead were placed either in the forks of the trees along the river bottom, or in lodges on the bluffs overlooking the river, where they would be left with blankets, guns or any other articles the Indians thought might be useful to the dead in the land to which all the plain Indians believe they will go after death. This point had also for all previous time with the Blackfeet been the scene of many a bloody battle between them and the Crees on the north, who on their hunts to the south would generally meet the Blackfeet at this point, in their endeavor to penetrate to the south by this ford.

As I have stated, during this spring many journeys had to be made with only a few men to this point, and our intervention, not by force, but quiet handling between the different bands of Indians, on more than one occasion prevented serious fights between the Blackfeet and other bands of Indians camped in that vicinity.

On some occasions when some horses had been stolen by either Crees or Blackfeet from each other, or some Indian had been killed, we found it best to let the chiefs of the camps settle the matter in their own way, for it must be understood that the old habits of the Indians could not be eradicated in two or three years, nor could the white man’s law be instilled into the Indians in such a short time.

If on any occasion any individual Indian of the same tribe had committed an offence against the law of the tribe, or any foreign Indian had been caught who had stolen horses, or who had killed a man of the tribe, the offence could always be condoned by the payment of a number of horses, according to the gravity of the offence, so that on many occasions we found it well to let them settle such matters in their own way, particularly as it was often most difficult to get direct evidence to convict. We had to use a great amount of circumspection in our first intercourse with the plain Indians.

A murder, the stealing of a woman or horses, could be, and was previous to our advent, always settle in this manner. The exception was only when a war party from a long distance started out, and in nearly all such instances, if caught, no mercy was shown or expected.

I made another journey to Edmonton during the summer of 1876, to bring down a half-breed prisoner fro that place, for murder committed some years before we arrived in the country. This man, Godin, had killed his wife in a particularly cruel manner, and so far had gone free, there being no power in the country to punish him. However, he was arrested by Colonel Jarvis shortly after the police arrived at Edmonton, and I was sent to bring him down, so that he could be sent to Winnipeg for trial.

I had a light wagon for provisions, etc., and for the prisoner, and before I left Edmonton Bishop Grandin, of Edmonton, requested to be allowed to join our party, as he wished to visit the Catholic Missions established the previous year at Fort Macleod and Calgary. It was the first time he had ever visited the southern country.

Our journey south was uneventful, excepting a very near escape of capsizing in the Red Deer river, the river being very high, and the flat bottomed boat very leaky.

The prisoner was sent down to Winnipeg, and afterwards released, as much influence was brought to bear in his favor by the Catholic missionaries in the north, the plea being his youth at the time the murder was committed, and the length of time that had elapsed. He was, however, arrested some years after, and put in a term for horse stealing, which he richly deserved.

Bishop Grandin remained some time in the south, making arrangements about establishing missions and other church work.

The first priest to visit us on our arrival at Macleod was Father Scullin, who had travelled more among the Blackfeet than any other missionary from the north. He proved of great assistance to us, as he could speak the language, and knew the country fairly well.

Nothing so far had been attempted in the way of converting the Blackfeet, and what missionary work he had done in the south was among the few half-breeds who would go on the plains on their annual hunts. These parties he would generally join, and remain with them during the summer, returning to Edmonton during the winter to the Catholic convent and mission, St. Albert’s, near Fort Edmonton, where there was also quite a half-breed settlement commenced.

Continued in Arrival of Sitting Bull.

Leave a Reply