Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XXX – The Northwest Rebellion.

Chapter XXXI

INDIANS OF THE SOUTH KEPT QUIET

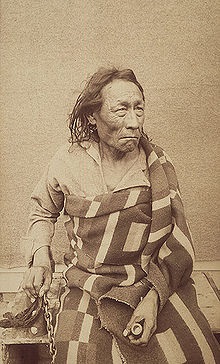

BY JUNE, 1885, the rebellion in the north might be said to have ended, with the exception of scattered bands of Indians who had taken to the woods in the far north. There were parties of police and scouts after these bands, and they were brought in one by one during the summer. On July 2, Big Bear, the leading Cree rebel chief, was captured by Sergeant Smart of the police, and the detachment with him, near Ft. Carleton. This chief, together with many other prisoners, was taken to Regina shortly afterwards for trial. The execution of Riel and other rebels some time afterwards, is too well-known for repetition.

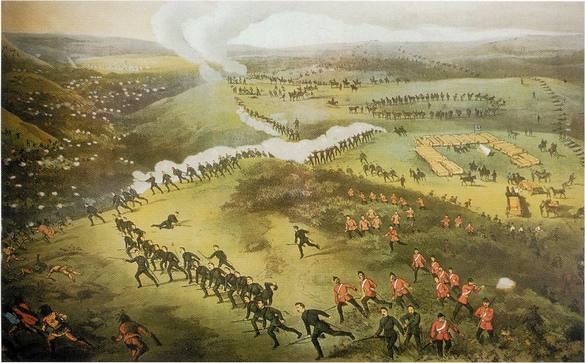

The officers and men in other parts of the north and operating with different militia regiments did good and valuable service. Superintendents W. Herchmer and Neal served with the column sent from Swift Current to the relief of Battleford; Superintendent Herchmer acting as second in command to Col. Otter, who reported both officers specially, for the services rendered by them at the fight at Cut Knife. Superintendents Steele and Perry held important commands while serving with the Alberta field force under General Strange in the country to the north and east of Edmonton, and were most highly commended by that officer for their ability, energy and zeal.

Superintendent McIllree did excellent work south of the C.P. railroad, watching the Cypress hills and to the boundary line, while Superintendent Cotton had his hands full in the west, in the Macleod district. All other officers and non-commissioned officers and men did their work most thoroughly and well.

At the fight at Cut Knife the police under Superintendent Herchmer showed the greatest bravery, two, Corporal Lowry and Trumpeter Burke, being killed in that action, and Sergeant Ward badly wounded. Superintendent Steele in command of a troop of scouts raised by him at Calgary, together with twenty-five police of the command that had been under him in the mountains, was present at all the operations of the Alberta field force under command of Major-General Strange, who speaks most highly of the work done by the police, stating in his report that during the whole of the operations of the Alberta field force, the Mounted Police with it behaved in the most exemplary manner,

and elicited the admiration of General Strange, and all the militia officers. He also particularly mentions Sergt. Ferry, Constables McDonald, McRae, Davidson, Bell, McMinn and Kerr, stating that all of the constables above mentioned performed the duties of non-commissioned officers to the scouts satisfactorily, and are able to do the work of either corporal or sergeant. “They have, owing to their experience on the Canadian Pacific railway, becoming thoroughly acquainted with the proper way of doing their duty as constables. I have no hesitation in saying they are collectively the best body of men I have ever had anything to do with. Sergt. Ferry and Constable McRae were wounded, the former at Loon Lake and the other at Frenchman’s Butte’ they are unable to do duty.”

The detachment of police that left Fort Macleod under Inspector Perry joined the Alberta field force under General Strange, and marched from Macleod to Edmonton and Ft. Pitt and back, 1,300 miles. They accomplished this, hauling a gun weight 38 hundredweights over roads sometimes nearly impassable, without the loss of a horse. Frequently the gun had to be dismounted from its carriage, and carried out of soughs in which the horses were mired, and as Inspector Perry stated in his report, the detachment of N.W.M. Police under his command has borne out the reputation for energy, pluck and endurance, which has been carried by the North West Mounted Police force during many years of long and trying service in the Northwest Territories.

At Fort Pitt Inspector Dickens (son of Charles Dickens), was besieged by the Crees under Little Pine with a very large following. These Indians had committed many murders, and were a pretty desperate lot. Inspector Dickens had to abandon the fort, and went down the

Saskatchewan river with his party, by road to Battleford, where they arrived without any loss; Fort Pitt was burnt to the ground by the Indians, after the police had left, but the Indians met with a heavy reckoning at the hands of the Alberta field force, a short time afterwards.

A sad death occurred at Batoche after the fight was over and the rebels defeated; Inspector J. French who was through the fight from beginning to end, and who had shown great bravery throughout, was standing at the window of a house in the village, looking down on the street that was filled with troops and civilians, when a shot was fired from among the crowd by an Indian, which- striking him in the heart- killed him instantly. The Indian was seized and riddled with bullets. Inspector French was a brother of Major General French, the first Commander of the force, and had been an officer in the Irish militia previous to joining the N.W.M. Police in 1874; he left a wife and large family, and being a favorite among his brother officers, his untimely death was much regretted. He was about the last man killed in that section during the rest of the rebellion.

In the south among the plain Indians, things had remained quiet during the summer. When word was received by telegraph at Fort Macleod of the Duck Lake fight, I was on a ranche about three miles from Macleod and was called up in the middle of the night by a message from Superintendent Cotton, commanding the police in that district, who was stationed at the fort. On going over, I found a great state of excitement existing in the fort, word having just been received of the outbreak of the rebellion in the north, and great uncertainty existed as to the attitude the plain Indians would take. Superintendent Cotton requested me to take charge of Treaty No. 7, and visit the Indians at once. This I declined to do, unless full power was given me to act as I deemed fit, stating that I had resigned the agency on account of orders received from Ottawa instructing me to act in a manner which I knew could only end in disaster. I, however, told him that I was quite ready to do anything I possibly could for the police or that would be of any advantage to the country.

He requested me to visit the Bloods, and find out their feelings and advise them to remain quietly on their reserves. This I agreed to do on the following day, when he and I together drove out to the Blood reserve. I sent messengers through the camps to call the Indians together, and a very large number collected. I gave them an account of what was going on in the north, and advised them to remain quiet on their reserves. They had a good deal to say, and many complaints to make, particularly that they had not enough to eat, but altogether the meeting was satisfactory. I promised them more food, in which I saw they were much in need. On our return to Macleod I found the following telegram awaiting me from the government: “You are authorized to act for the government in Indian matters in any way which you may deem advisable. E. Dewdney, Lieutenant-Governor Northwest Territories.”

I therefore determined to take charge of the treaty for the summer, and notified the Indian commissioner accordingly; I also instructed the agent at the Bloods to increase the rations of beef on that reserve at once, and I started for the Blackfoot crossing as soon as possible, it being the most important point in the treaty, and the agent, Mr. Begg being away, it was most necessary that I should not lose any time in getting there. I found the Blackfeet even more excited than the Bloods, as messages had been received from the Crees and half-breeds asking the Blackfeet to join them. They also complained of not having enough food, so I increased their rations to the same as the Bloods. I remained a week with them, going from camp to camp, and when I left for Calgary, I was sure that there would be no trouble caused by the Blackfeet. I found quite an excitement at Calgary, as false rumors had been circulated there as to the attitude of the Blackfeet, and it was reported that they intended to make a raid on the town. These fears I soon quieted, and after visiting the Sarcees and Stonies, and leaving them quiet, I returned as quickly as possible to Macleod.

Matters had remained quiet at Fort Macleod, a corps of scouts under Captain Stewart had been raised, and had gone to Medicine Hat. I visited the Piegans and Bloods several times, and finding no danger to be apprehended from them, I returned to the Blackfoot crossing. I remained among the Blackfeet until the close of the rebellion, making an occasional trip to Calgary and several to the Bloods and Piegan reservation. I had not the slightest trouble with any of these Indians, who behaved well. I formed a corps of Blackfeet scouts, and sent many of them north to keep me posted as to movements in that section, and they did this work most satisfactorily. I had continual communication with the Lieutenant-Governor, who kept me informed of what was going on in the north, and I finally persuaded him to pay a visit to the Blackfeet, who were most anxious to see him. A great council was held, which went off very quietly, and many promises were made to the Indians, which were, as usual, broken in after years. Sir John Macdonald telegraphed from Ottawa to Crowfoot the head Blackfoot chief as follows: “The good words of Crowfoot are appreciated by the big chiefs at Ottawa. The loyalty of the Blackfeet were never be forgotten. Crowfoot’s words shall be sent to the Queen. All Mr. Dewdney’s promises shall be faithfully carried out.” (15-4-85- Forwarded to Mr. C.E. Denny, Fort Macleod.)

Yet, in spite of the above, a year had not passed before the rations were again cut down, and have been so ever since. With the exception of the Lieutenant-Governor and his party, there were but few visitors to the Blackfeet during the summer; and with the exception of the Church of England clergyman and the Catholic priest, who both remained steadily at their posts, no other missionaries visited us, although it has been reported otherwise. Father L’Comte visited the reserve once, and that was with the Lieutenant-Governor’s party. I received a letter from him Calgary during the summer asking me to go to that place and send a party of Blackfeet away, who were camped there’ this I did. I also during the summer received the following telegram, which speaks for itself:

“Regina, May 1st.

“A few Crees, some thirty in number, skulking around Cypress. Would like Blackfeet to clean them out. Could this be done quietly? Advise me before taking action.”

To this I replied as follows:

“Blackfoot Crossing, May 1st.

“Better not send Blackfeet; would all wish to start out. Could not keep track of them.”

It can, therefore, be seen what there was to contend against. Not only was there plenty of work required to keep the Indians quiet on their reserves, but you also had to combat orders issued with an utter ignorance of Indian ways. The result of such an action as that advised above would have taken all the able-bodied Indians out of Treaty No. 7 and have started a nice little war to get them back again. I might relate more of these wise moves, but I think the one is sufficient, and if the northern Indians, before the rebellion, were handled in the same manner, there is no wonder that the outbreak took place.

Superintendent Cotton at Fort Macleod patrolled eastward towards the Cypress Hills during the summer, and did good service. Mr. Pocklington, Indian agent to the Bloods, and myself visited them in May. A copy of a portion of my report I give, as it shows how many different matters, small in themselves, tended to make the Indians uneasy, and these had all to be particularly explained to them. The raising of companies of scouts at Calgary and Macleod they could not at all understand, and there were always evil-disposed persons who would tell them that it was the intention to attack them, and, unless these reports were contradicted, much trouble might have been caused.

“Fort Macleod, 17th May, 1885.

“To the Indian Commissioner at Regina.

“Sir,- I have the honor to report that Mr. Pocklington and myself visited the Blood reserve yesterday, and held a council with the Indians. I gave them the message you gave Crowfoot, and also his reply, and a message Crowfoot sent by me to the Bloods and Piegans, to the effect that they were to remain quietly on their reserves at work. The Bloods had a few complaints to make, but most of them were easily settled. Mr. Pocklington had seen Mr. Cochrane, and will take possession of his place next week; an issue house will be established there, much to the satisfaction of the Indians. It was necessary that the beef rations of the Bloods should be increased, as they had already heard that the Blackfeet have extra beef. This extra ration through this treaty was most necessary, as the ration they were getting was barely enough to keep them alive. I am glad to say that I had an opportunity to place Mr. Pocklington on a sound footing with the Bloods, who had held him responsible for many refusals to applications made by them for articles, etc., which he had no authority to grant.

“The Bloods, if quietly handled during this summer, will not leave their reserves, but work on their farms. It is most important in dealing with the Bloods, Blackfeet and Piegans, this summer, that their attention should be withdrawn from anything going on outside of this treaty. There will, no doubt, be a change in garrison of the different police posts at Calgary and Macleod, and strict instructions should be given that, when it is necessary for these new men to visit our Indian camp for the purpose of m

aking an arrest, they should be accompanied by an officer of the Indian Department known to the Indians, and that in no case should a party of militia go to an Indian camp without this step being taken.

“My reason for this is that the Indians are used to the police going into their camps for prisoners, but do not understand men dressed in another uniform doing this duty. Just before I left the crossing, quite a stir was made in the upper Blackfoot camp by Major Hatton, from Calgary, entering that camp in the middle of the night with a party of militia on a patrol, and great excitement prevailed for several days.

“It was only very rarely that any of the militia in the west visited the reserves, those in command being always most careful on that point, leaving much matters altogether in the hands of the police and Indian department, who brought the Indians of Treaty No. 7 quietly through the year 1885 without a hitch, while had inexperienced hands held the reins an outbreak of the Blackfoot tribe would most certainly have taken place, causing great loss of life and property, to say nothing of the cost.

“I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

“C.E. DENNY, Indian Agent.”

Continued in Chapter 32: After the Northwest Rebellion.

Leave a Reply