Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XXXI – Indians of the South Kept Quiet.

Chapter XXXII

AFTER THE NORTHWEST REBELLION

ALL THE MILITIA stationed in the west were withdrawn by the fall of 1885, and the scouts disbanded. All men of the militia, and those engaged as scouts, received land grants for their services, but the police received none; a most unjust and unwarranted measure. These men had borne the burden and the heat of the day all through 1885, doing their work in grand style, work that only long training could fit them to fulfil, but on account of their being a regular corps, a land grant which all others received, including many of those who did no work at all, was denied them. Thanks and promises were profuse after the rebellion, and that was about all. I myself received thanks in a flowing letter, which I still have, and also the promise of a permanent position, which was, of course, unfulfilled.

On the withdrawal of the militia forces, the police force was increased to 1,000 men, up to which strength it has continued, until recently, and many new detachments were posted at different points throughout the country. Telegraph lines were also constructed from different points on the Canadian Pacific to points such as Macleod, Lethbridge, Wood Mountain, etc.

On the withdrawal of the militia forces, the police force was increased to 1,000 men, up to which strength it has continued, until recently, and many new detachments were posted at different points throughout the country. Telegraph lines were also constructed from different points on the Canadian Pacific to points such as Macleod, Lethbridge, Wood Mountain, etc.

The whiskey traffic had increased during the summer of ’85, as most of the points along the line were left unwatched. Horse stealing had also become common, many American Indians and white men making a business of it during this summer.

This horse stealing was not along confined to the Northwest, but a police detachment under Inspector Saunders was stationed in southern Manitoba, and found this crime rife. He, however, put a complete stop to it, and, on returning to headquarters in the fall of ’85, reported that for some time previous to his leaving not a case was reported.

Inspector Steele had been stationed with a strong detachment in the mountains along the line of the C.P. railroad, and his work, although difficult, was completely performed. He remained there until his services were required to take charge of a force, which, as I have already mentioned, operated under General Strange. An extract from his report will show the work he had to do. He states:

“About the 1st of April, owing to wages being in arrears, 1,200 of the workmen struck where the end of the track then was, and informed the manager of construction that, unless paid up in full at once, they would do no more work. They also openly stated their intention of committing acts of violence upon the staff of the road, and of destroying property. I received a deputation of the ringleaders, and assured them that if they committed any acts of violence, and were not orderly in the strictest sense of the word, I would inflict upon the offenders the severest punishment the law would allow me. They saw the manager of construction, who promised to accede to their demands, as far as lay in his power, if they would return to their camps, their board not to cost them anything in the meantime. Some were satisfied with this, and several hundred returned to their camps. The remained stayed at the Beaver (where there was a population of 700 loose characters), ostensibly waiting for their money. They were apparently very quiet, but one morning word was brought to me that some of them were ordering tracklayers to quit work, teamsters freighting supplies to leave their teams, and bridgemen to leave their work. I sent detachments of police to the points threatened, leaving only two men to take charge of the prisoners at my post. I instructed the men in charge of the detachments to use the very severest measures to prevent a cessation of the work of construction.

“On the same afternoon Constable Kerr, having occasion to go to the town, saw a contractor named Rehan, a well known desperado (supposed to be in sympathy with the strike) drunk and disorderly, and attempted to arrest him. The constable was immediately attacked by a large crowd of strikers and roughs, thrown down, and ultimately driven off. He returned to barracks, and on the return of Sergeant Fury with a party of three men from the end of the track, that non-commissioned officer went with two men to arrest the offending contractor, whom they found in a saloon in the midst of a gang of drunken companions. The two constables took hold of him and brought him out, but a crowd of men, about 200 strong and all armed, rescued him, in spite of the most resolute conduct on the part of the police. The congregated strikers aided in the rescue, and threatened the constables when they persisted in their efforts.

“As the sergeant did not desire to use his pistol, except in the most dire necessity, he came to me (I was on a sick bed at the time), and asked for orders. I directed him to go and seize the offender, and shoot any of the crowd who should interfere. He returned and arrested the man, but had to shoot one of the rioters through the shoulder before the crowd would stand back. I then requested Mr. Johnston, J.P., to explain the riot act to the mob, and inform them that I would use the strongest measures to prevent any recurrence of the trouble. I had all the men who resisted the police, or aided Rehan, arrested the next morning, and fined them, together with him, $100 each, or six months’ hard labor.

“The strike collapsed next day. The roughs, having had a severe lesson, were quiet. The conduct of the police during this trying time was all that could be desired. There were only five men at the Beaver at the time, and they faced the powerful mob of armed roughs with as much resolution as if backed by hundreds.

“While the strike was in progress, I received a telegram from His Honor the Lieutenant-governor of the Northwest Territories, directing me to proceed to Calgary at once with all the men, but in the interests of the public service I was obliged to reply, stating that to obey was impossible until the strike was settled.

“On the 7th day of April the laborers had all been paid and I forthwith proceeded to Calgary, leaving the men in charge of Sergt. Fury; everything was perfectly satisfactory.”

In the early part of the winter of 1885, I reported to the Government that it was not necessary for me to act for them among the western Indians, any further, everything being quiet and the agents well able to do their work. Having retired to my ranche near Macleod, a telegram was brought me from the Lieutenant-governor at Regina, requesting me to pay him a visit at that place. I therefore proceeded to Regina, and found that Mr. Dewdney had just returned from Ottawa, and he stated that the Government were still most anxious about the Indians in the west, and that he had the premier’s authority to request me to remain among the western Indians, and watch their movements, and keep him well informed of them during the winter. I was at first rather disinclined for any more work under that department, but he informed me that if I would accede to his request a permanent appointment would be tendered me in the spring. I therefore agreed to do as requested, and returned to Macleod, visiting the reserves often during the winter, and keeping matters straight. Among other things I was informed during the winter that it was the intention of the Government to sent troops into the west, to show the Indians the power of the Government, and I was asked my opinion, which I most decidedly gave in the negative, the Indians all being quiet. Such a step would only have caused fresh trouble to arise. The project was, therefore, wisely abandoned.

The following spring, as there was no sign that the promises made me would be fulfilled, and as, in fact, the opposite was the case, I a third time severed my connection with the Canadian Indian department, leaving all quiet on the different reservations.

The country, after the rebellion, and since the railroad was built, had grown rapidly in population, and much stock was brought in. The work of the police was now different altogether to what it had been in the previous years, a railroad was built through the country, and branch lines were building; good, comfortable buildings had been erected in place of the old log forts; the transport was excellent, and food and clothing were of the best quality. The long journeys that used to be made were now a thing of the past, as small detachments, with good buildings, were stationed at different points along the Indian reservation and along the boundary lines. But the force was as necessary as in the old days, or even more so, and will continue to be so for many years to come. Although a shortsighted policy of late years has decreed the reduction of this splendid and necessary force, it will eventually be found that the country, for a long time to come, cannot get on without them, considering the multiplicity of duties performed by this force. Although for some years past, owing to the false Government policy, the southern portion of these Territories has been at a standstill as far as settlement goes, it is still imperative that a strong force should be along the boundary line, in close proximity to Indian reserves and cattle ranches, as well as the white settlements scattered through the country. It is a duty that can only be performed by such a force as the Mounted Police, who have had long experience and training in the country itself. There may not be, and probably is not, any necessity for a large police force at a place like Regina, or even Calgary, but in the south and north the time will be long in coming before they can be dispensed with. Less centralization and more scattering of the force in small detachments should now be the policy, as the time is past when an Indian outbreak in the west can be looked for, and as the settlement of this western country is for some cause very slow, the few ranches and villages are wide apart, and it is at those points that police are required.

The country, after the rebellion, and since the railroad was built, had grown rapidly in population, and much stock was brought in. The work of the police was now different altogether to what it had been in the previous years, a railroad was built through the country, and branch lines were building; good, comfortable buildings had been erected in place of the old log forts; the transport was excellent, and food and clothing were of the best quality. The long journeys that used to be made were now a thing of the past, as small detachments, with good buildings, were stationed at different points along the Indian reservation and along the boundary lines. But the force was as necessary as in the old days, or even more so, and will continue to be so for many years to come. Although a shortsighted policy of late years has decreed the reduction of this splendid and necessary force, it will eventually be found that the country, for a long time to come, cannot get on without them, considering the multiplicity of duties performed by this force. Although for some years past, owing to the false Government policy, the southern portion of these Territories has been at a standstill as far as settlement goes, it is still imperative that a strong force should be along the boundary line, in close proximity to Indian reserves and cattle ranches, as well as the white settlements scattered through the country. It is a duty that can only be performed by such a force as the Mounted Police, who have had long experience and training in the country itself. There may not be, and probably is not, any necessity for a large police force at a place like Regina, or even Calgary, but in the south and north the time will be long in coming before they can be dispensed with. Less centralization and more scattering of the force in small detachments should now be the policy, as the time is past when an Indian outbreak in the west can be looked for, and as the settlement of this western country is for some cause very slow, the few ranches and villages are wide apart, and it is at those points that police are required.

It is not my intention to carry this book beyond the spring of 1886, although at some future time I may do so, and also give a fuller account of the rebellion in 1885, but I have endeavored in this short volume to show the actual police work performed, and necessarily had to include much Indian and Indian department matter.

Many of the old officers and men engaged in the force in the years comprised in this volume are dead, and as time passes there is less likelihood of an account of the work done ever being written, and I have therefore written, although with but few books or reports to refer to, most of the old reports having long since been destroyed, with a personal knowledge of the subject throughout, and with the thought that

some record should be left by one actually engaged in the work of the splendid services rendered by the Northwest Mounted Police to the Canadian Government and the country generally. I have endeavored to do this, and although most incomplete and faulty in many respects, I have at least told in a short form, facts, and left on record a short history of the police work in the early days.

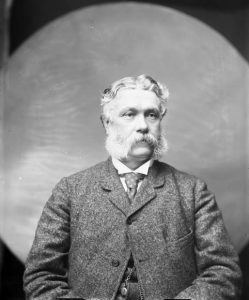

I might mention that during the summer of 1885 one of the oldest officers, Superintendent Winder, died at Fort Macleod. He had left the force a few years previously, having been one of the first to get a commission in 1873, and going through all the hardships we all underwent. He started, after leaving the force, one of the first cattle ranches in southern Alberta, which was, and still is, most successful. His loss left another gap amongst the old policemen, which is year by year growing wider, and it will only be a few years before we shall all be of the past, and ourselves and our work forgotten, as must happen with nearly all old pioneers, although the result of their work may remain a monument for ever.

Continued in Chapter 33: Some Advice to Settlers.

Leave a Reply