The Miracle at Loon Lake

For Christians the world over, this year’s Holy Week- the week preceding Easter Sunday- is overshadowed by the tragic immolation of Notre-Dame de Paris. On April 15, 2019, millions of Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians watched in horror as the vaulted ceiling of that magnificent, 850-year-old symbol of Christendom went up in flames. The structure burned for fifteen hours before collapsing into the nave below, mercifully damaging little of the cathedral’s historic interior.

Despite eclipsing it in scale, this disaster eerily echoes the cremation of another house of God by the name of ‘Notre Dame’ which took place in the Holy Week of 1885, on the northern edge of the Albertan prairies. A savage act of arson, this event played a pivotal role in the story of one of Saskatchewan’s least known and most baffling historical mysteries.

Whispers of Revolution

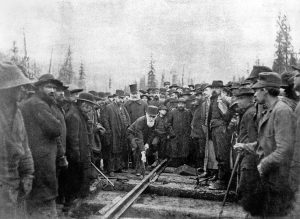

1885 was a year of transition in the Canadian West, marking the end of one era and the beginning of another. That fall, the Last Spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway- the iron road connecting the easterly Dominion of Canada with the westerly Province of British Columbia, and bridging the vast North-West Territories that lay in between- was driven home at Craigellachie, B.C. The ringing of the sledgehammer might have served as a summoning bell for hordes of homesteaders who would soon pour into the Canadian prairies, and as a death knell for the days of Canada’s brief and fiery Wild West. By 1885, the huge herds of buffalo that had blanketed the prairies since time immemorial had dwindled to near extinction, destined to be replaced in a few short years by their domestic counterparts, beef cattle. The traders, prospectors, and wolfers who, decades prior, had comprised the North-West Territories’ only white civilian population had gradually traded in their repeating rifles and revolvers for the lasso of the rancher and the pitchfork of the farmer. And the Blackfoot, Cree, and Assiniboine Indians who had once dominated the region on horseback had been coerced by the Mounties, who brought law and order to the Canadian West in 1874, to abandon the nomadic lifestyle of their ancestors and settle onto Reserves, where their livelihood was reduced to waiting for government rations.

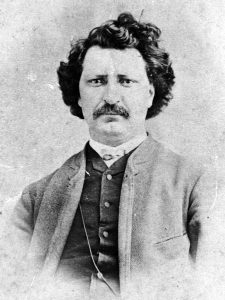

Naturally, there were many who were vigorously opposed to these changes that were swiftly reshaping the face of Western Canada. Foremost among these were the Metis people- the progeny of French-Canadian and Scottish fur traders and Cree and Ojibwa women. Nearly two decades prior, in the wake of Canadian Confederation, the French Metis of the Red River Valley south of Lake Winnipeg had rebelled against the newly-established Canadian government, fearful that Dominion agents would force them to abandon their homesteads along the Red River, which they did not legally own. The uprising, called the Red River Rebellion, was led by a well-educated Metis revolutionary named Louis Riel, who fled south to Dakota Territory when the Canadian government sent a military expedition to enforce peace in the region.

By 1885, the Metis people, who had relied on the bison almost as heavily as their First Nations cousins to the west, were in dire straits. That spring, they invited Riel to return from his long exile in the United States in the hope that he might lead them once again in this their time of need. Answering the call of his people, the Metis expatriate rode north into Canada and up the wagon-rutted Carlton Trail to the village of Duck Lake in what is now Central Saskatchewan, where many Metis had resettled following the Red River Rebellion. In no time, whispers of an upcoming revolution were rippling throughout the Canadian prairies.

The Frog Lake Massacre

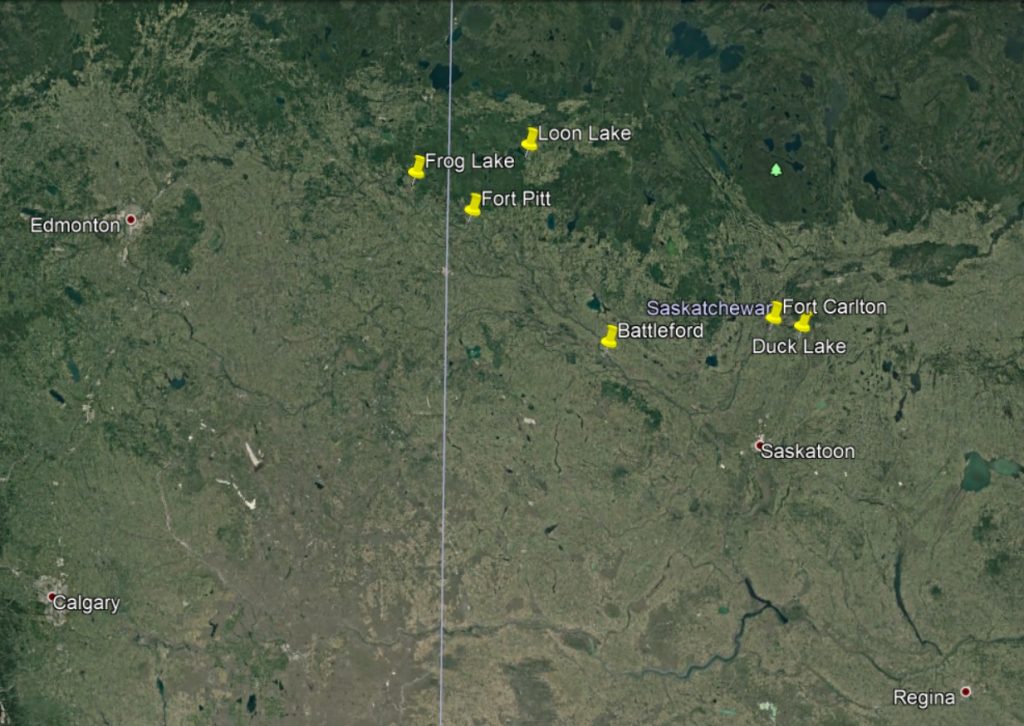

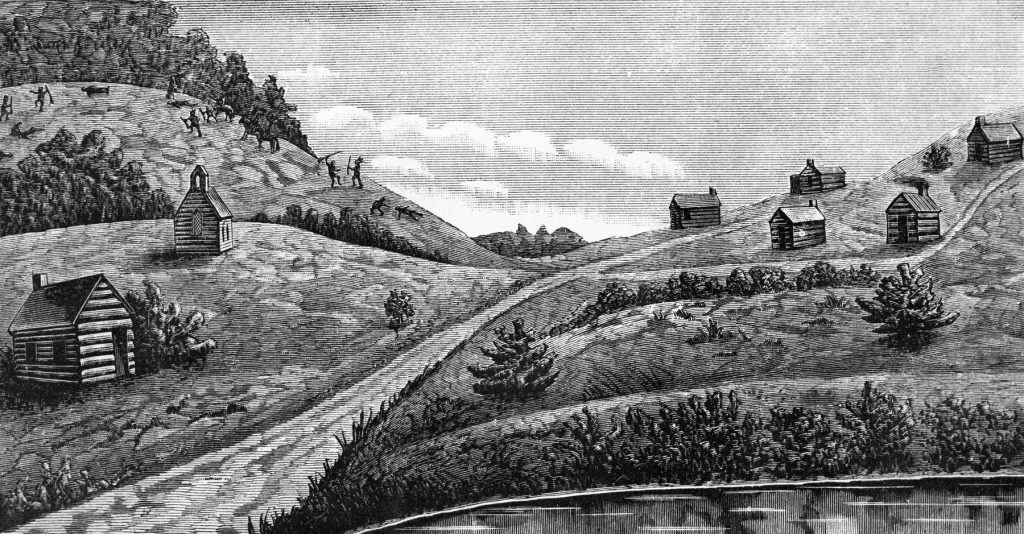

About 300 kilometres (185 miles) northwest of Duck Lake, just west of the eastern border of what is now Alberta, at a place where the southerly prairie meets the boreal forest, lies the settlement of Frog Lake. In 1885, this tiny community boasted a grist mill; a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post; a small North-West Mounted Police barracks and stables; a Catholic Mission church called Notre Dame du Bon Conseil, or ‘Our Lady of Good Council’; and an office for Indian Agent Thomas Quinn, who was responsible for the three bands of friendly Woodland Cree who pitched their teepees nearby.

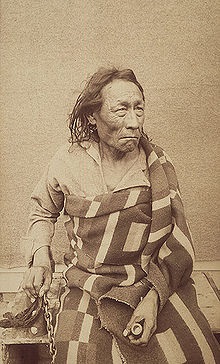

In the spring of 1885, while Louis Riel was receiving a warm welcome at Duck Lake, two very different Cree bands joined their fellows at Frog Lake. One was comprised of the so-called ‘Bush Indians’, a peace-loving clan of Chipewyan Dene who hailed from the forests to the north. The other was composed of fearsome Plains Cree from the southerly prairies who were led by a grizzled, pox-scarred chief named Big Bear.

Big Bear was a true member of the old guard- a man with one moccasin firmly planted in the past and the other begrudgingly thrust into the present. He was the veteran of a thousand skirmishes and horse raids, having spent most of his adult life on the warpath against the Blackfoot, his people’s hereditary enemy. He had even played a prominent role in the 1870 Battle of Belly River– the world’s last great intertribal Indian battle. Like his ancestors before him, his sole occupations prior to the coming of the Mounties in 1874 had been hunting and warfare- activities which, in his mind, tested his mettle as a chief and defined his worth as a man.

Big Bear detested the changes that had taken place in recent years and stubbornly refused to give up the traditional Plains Cree way of life. Hoping to retain his freedom for as long as possible, he was the last chief to sign Treaty 6- an agreement between the Canadian government and the various Cree and Assiniboine nations of what is now Alberta and Saskatchewan, which stipulated that the natives surrender their hunting grounds to the government in exchange for provisions. When the buffalo finally disappeared from the prairies and his people began to go hungry, Big Bear had no choice but to accept the terms of the treaty. Instead of settling on a reserve as had his contemporaries, however, the old chief and his band attempted to retain some semblance of their traditional nomadic lifestyle, spending nearly a decade wandering aimlessly from trading post to trading post without any buffalo to pursue. When they finally rode into Frog Lake (where they intended to spend the winter) in the spring of 1885, they were bitter, frustrated, and hungry.

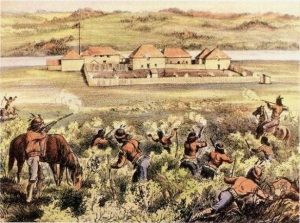

On March 30, 1885, word reached Frog Lake of a battle which had taken place five days prior at southeasterly Duck Lake. On March 19, Louis Riel had declared himself the leader of the so-called ‘Provisional Government of Saskatchewan’- an independent Metis state comprising much of what is now Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. When a handful of North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) officers from Fort Carlton (a Hudson’s Bay Company post located about 20 kilometres (13 miles) northwest of Duck Lake, on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River) had attempted to make a routine trip to Duck Lake for supplies, Metis revolutionaries had stopped them on the trail and forced them to return with a message from Riel demanding the fort’s peaceful surrender. Leif Crozier, the Superintendent of Fort Carlton’s NWMP detachment, had no intention of giving in to Riel’s demands. On March 25, he led 95 Mounties down the road to Duck Lake, where 250 Metis revolutionaries were waiting for them, having occupied a defensive position behind several log cabins at the edge of a thicket. Led by their general, Gabriel Dumont, the Metis militia engaged Crozier’s force in a 30 minute firefight which left 12 Mounties and 6 Metis dead. Heavily outnumbered, Crozier had no choice but to retreat to Fort Carlton. And thus Riel and his forces won their first victory in what would come to be known as the North-West Rebellion.

The Plains Cree at Frog Lake were encouraged by news of Riel’s success, and almost overnight, Big Bear’s son, Imasees, determined to start his own rebellion and fight his way across the prairie to join forces with the Metis malcontents; his father, the old chief, was away on a hunting trip at the time. Eager as he was for an opportunity to change the his people’s pitiable circumstances, however, Imasees’ enthusiasm for the upcoming conflict was eclipsed by that Wandering Spirit, a hotheaded, curly-haired sub-chief who held more sway over the band’s young braves than even Big Bear himself. Wandering Spirit hated white men and blamed them for all the problems the Cree people were currently facing. When Frog Lake’s eight Mounties left for Fort Pitt (a Hudson’s Bay Company post located 50 kilometres (30 miles) southeast, on the banks of the North Saskatchewan) at the request of Frog Lake’s white residents, who thought their presence might provoke the Plains Cree to violence, Wandering Spirit decided that the time had come to mete out Indian justice.

Big Bear returned to Frog Lake from his hunting trip on the evening of April 1, where he learned of Riel’s rebellion and of Imasees and Wandering Spirit’s desire to take to the warpath. Weary from his journey, he went to sleep, whereupon Wandering Spirit and his most loyal braves painted their faces with blood red vermillion and yellow ochre before stealing the horses from the unguarded Mountie stables.

On the morning of April 2, Wandering Spirit and his warriors broke into the homes of Frog Lake’s white residents and seized their firearms. “Riel and his half-breeds came last night and stole the red coats’ horses!” the Plains Cree lied to the bewildered settlers. “But don’t be afraid. We will protect you.”

After raiding the HBC post of its knives, bullets, and gunpowder, the warriors herded most of Frog Lake’s white settlers to the Mission church, where the resident priest, Father Farard, and a visiting priest named Father Marchand, were saying Holy Thursday Mass for the local Metis and Woodland Cree. In the middle of the service, Wandering Spirit sauntered into the church and genuflected in the centre aisle, a Winchester rifle in his hand. According to 23-year-old HBC clerk William Bleasdell Cameron, a witness of the event who described the experience in his 1926 book Blood Red the Sun:

“His lynx-skin war-bonnet, from which depended five large eagle plumes, crowned his head; his eyes burned and his hideously-painted face was set in lines of deadly menace. Never shall I forget the feelings his whole appearance and action excited in me as I watched in stupefied amazement while he half-knelt, glaring up at the altar and the white-robed priests in sacrilegious mockery. He was a demon, a wild animal, savage, ruthless, thirsting for blood. I doubted then that we should any of us ever again see the outside of the chapel.”

Fathers Fafard and Marchand concluded the Mass prematurely on account of Wandering Spirit’s hostile antics, whereupon the war chief’s followers ushered most of the white settlers towards the Plains Cree camp. Wandering Spirit himself headed to the home of Thomas Quinn and ordered the Indian agent to follow his white compatriots. Quinn refused. Wandering Spirit repeated his demand twice more, and each time the government man refused to comply. “Die then!” spat the war chief, raising his rifle and shooting Quinn in the head.

The gunshot was like a spark in a powder keg. Immediately, a Plains Cree warrior shot Quinn’s Metis interpreter in the shoulder; another pockmarked brave then ran up to the wounded man, pressed the muzzle of his rifle against his chest, and finished him off.

Chief Big Bear, who had been lounging in the kitchen of the HBC post, ran towards the bloody scene bellowing “Tesqua! Tesqua!” (Stop! Stop!) in a great booming voice. His entreaty fell on deaf ears; two more white men- William Gilchrist and George Dill- were subsequently murdered by Wandering Spirit’s unruly warriors, as were Fathers Fafard and Marchand.

“Dust and smoke filled the air,” wrote William Cameron. “Whoops and shrieks and the ghastly clatter of galloping hoofs blended in a weird and ghastly symphony. High over all swelled the deadly war-chant of the Plains Crees, bursting from a hundred sinewy throats. I heard the peculiarly-ringing voice of Wandering Spirit calling on his followers to shoot the other whites and burst after burst sounded the death knell of other of my friends.”

At that time, Theresa Gowanlock, the wife of a local miller named John Gowanlock- was among the crowd of white settlers who were being led to Big Bear’s camp. She described her harrowing experience in a later reminiscence entitled Two Months in the Camp of Big Bear, writing:

“Mr. Williscraft, an old grey-headed man about seventy-five years of age came running by us, and an Indian shot at him and knocked his hat off, and he turned around and said, ‘Oh! Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!’ But they fired again, and he ran screaming and fell in some bushes.”

“My dear wife,” whispered Theresa’s husband, John, in an attempt to comfort her, “be brave to the end.” No sooner had he said this than he was fatally shot in the back. Theresa fell down beside her dying husband and prepared herself for the inevitable bullet. “But death just then was not ordained for me,” she wrote. A Plains Cree warrior roughly hauled her to her feet just in time for her to see the murder of John Delaney, who had formerly instructed the local Woodland Cree in farming; Delaney’s grieving widow, who was also named Theresa, was torn from her husband’s prostrate body and made prisoner.

By the time the smoke cleared, nine white men lay dead and four white residents- Theresa Gowanlock, Theresa Delaney, William Cameron, and HBC agent James Simpson- were held captive in the camp of Big Bear. That Cameron and Simpson were spared the slaughter is due to the intercession of their Woodland Cree friends, who sheltered them in their own camp after the shooting broke out. Similarly, the two female prisoners, Mrs. Gowanlock and Mrs. Delaney, were saved from cruel usage and death by local Metis interpreters named John Pritchard and Adolphus Nolin, who purchased them from the braves who had claimed them as their wives.

The Plains Cree spent the following days feasting and dancing, gorging themselves on HBC bacon and sacramental wine from the Mission church. After mutilating the bodies of their victims, they allowed several devoutly Catholic local Metis to inter some of the bodies in empty houses and the church cellar; others were left out in the open at the command of Wandering Spirit, at least one of them being propped up against a tree with a pipe jammed in his mouth in a perverse display of frontier humour.

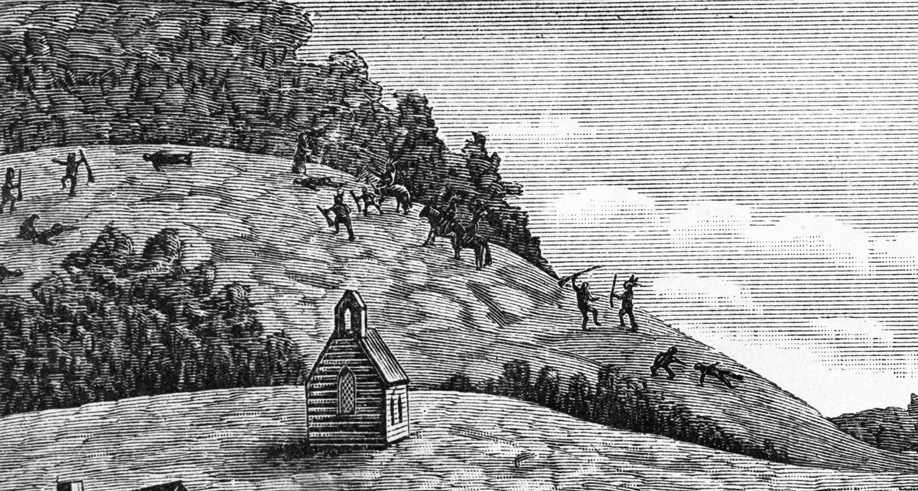

On Easter Sunday, Big Bear’s Plains Cree burned Notre Dame, the Mission church, before setting fire to the rest of the buildings at Frog Lake. That accomplished, they and their Woodland Cree brethren, whom they had bullied into joining their wild crusade, proceeded southeast, bound for Fort Pitt.

Big Bear’s Campaign

For two months, the Cree war party roamed throughout northern Saskatchewan with their prisoners in tow. Theresa Gowanlock, Theresa Delaney, and William Cameron, in their memoirs, detailed the particulars of the campaign, describing the Cree’s nearly bloodless capture of Fort Pitt; the constant infighting that took place between the warlike Plains Cree and the more peaceably inclined Woodland cousins; various Cree ceremonies, including the agonizing Thirst Dance and a ritualized feast which centred around the consumption of dog stew; and the Cree’s final skirmishes with government forces at the edge of the boreal forest. All the while, the prisoners- particularly those of the fairer sex- suffered from bitter cold, severe privation, and the ever-looming threat of execution at the hands of Wandering Spirit.

After their defeat at the Battle of Loon Lake, the Plains Cree and the Woodland Cree went their separate ways, the prisoners proceeding under the protection of their Woodland Cree friends. The captives were finally rescued by government forces in mid-June and brought back to civilization.

Most of the surviving perpetrators of the massacre at Frog Lake were eventually captured, although some of them escaped to Montana. On November 27, 1885, six of the culprits, along with two Cree and Assiniboine murders from the band of Chief Poundmaker, another participant in Riel’s rebellion, were executed at Fort Battleford in what was to be the largest mass hanging in Canadian history. Chief Big Bear himself, who had eluded government forces sent to capture him, eventually turned himself in at Fort Battleford. Due in part to the testimony of William Cameron, who described Big Bear as an unwilling participant in the campaign that was ascribed to him, the great Plains Cree chief was sentenced to three years of imprisonment.

The Miracle at Loon Lake

In October 1955, an article entitled ‘Memories of Frog Lake’ was published in the Montreal-based magazine Family Herald and Weekly Star. The piece was submitted by Arthur Johnson, nephew of Theresa Gowanlock, who claimed it to be a second memoir of the North-West Rebellion written by his aunt shortly prior to her premature death in 1899; indeed, the narrative’s style corresponds perfectly with that of Gowanlock’s in Two Months in the Camp of Big Bear.

According to the late Canadian writer Francis Dickie in articles for various Western magazines, the unedited original manuscript on which ‘Memories of Frog Lake’ was based contains a startling anecdote which Mrs. Gowanlock failed to include in her earlier memoir, presumably for fear of ridicule. Dickie claimed that this story was corroborated by the writings of Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, an Oblate missionary who “took down the statements of Indian and Metis prisoners” in the months that followed the rebellion; the author of this piece has been unable to verify this claim.

According to the original manuscript, the progress of Big Bear’s campaign was hampered by the foreboding of an old woman who portended disaster for the Cree. Gowanlock wrote:

“Her predictions that terrible things would overtake the band for their share in the killing of the priests unnerved the Indians. Then one morning a young brave, with an axe in his hand, led the old woman away. He returned alone.

“Late in the afternoon some days after this, toward the end of May when we had been captive eight weeks, as Mrs. Delaney and I were inside the lodge, we heard cries of consternation outside. We ran out to see all the band staring in fright at the sky. There in a break among low clouds was a representation of a church resembling that at Frog Lake burned down nearly two months ago with the bodies of the priests and the other white men. As we gazed a priest on a white horse appeared approaching the church. Reaching it he dismounted, stretched out his hand as if in blessing. The summer clouds closed in, and the vision faded away.

“Fear possessed all in the camp. The warning of the murdered old woman was recalled. The squaws, wearied by two months of extra labor of continually moving camp set up a wailing. The warriors had lost the last of their courage. Even the evening meal was untouched. And now the headmen began accusing the young braves of having caused the trouble. The camp did not move again.

“The end had come. A troop of soldiers travelling fast surrounded the camp two days later. Under a flag of truce the officers and the Chief met, and the Indians surrendered.”

It is interesting to note that several elements of Gowanlock’s manuscript, particularly the execution of the old woman and the vision in the sky, evoke events she had described in her earlier memoir. In Two Months in the Camp of Big Bear, Gowanlock claimed that, on Easter Monday, 1885, after a night of heavy storm:

“…The Indians came in and told us what they saw in the heavens. They saw a church and a man on a large black horse with his arm out and he looked so angry, and they said God must be angry with them for doing such a thing…”

Later on, Theresa Gowanlock described the Cree’s execution of a senile old woman who exhibited the symptoms of Wendigo psychosis- a mental malady characterized by a strange desire to eat human flesh, which the Cree attributed to the woman’s possession by an evil cannibalistic spirit. This event, which William Cameron described in gruesome detail in his book Blood Red the Sun, is hauntingly reminiscent of Gowanlock’s story about the old woman whom the Cree executed for her disturbing prophecies.

Is it possible that Gowanlock’s 1899 reminiscence is the product of the fevered brain of a dying woman- an inadvertent perversion of the events described in her earlier memoirs? Or did Mrs. Gowanlock, Mrs. Delaney, and members of the Cree war party truly see something extraordinary in the sky in the summer of 1885? Until we unearth the writings of Bishop Grandin alluded to in Francis Dickie’s writings, the answers to these questions will likely remain a mystery.

Sources

- What Saved Mrs. Gowanlock? by Francis Dickie in the Nov. 1964 issue of Real West

- Two Months in the Camp of Big Bear (1885), by Theresa Gowanlock and Theresa Delaney

- Blood Red the Sun (1926), by William Bleasdell Cameron

- Capturing Women: The Manipulation of Cultural Imagelry in Canada’s Prairie West, by Sarah Carter

- The Last Hostage (1968) , by Duncan McLean as told to Eric Wells, “Weekend Magazine No. 32”

- An Opinion of the Frog Lake Massacre, by Rev. Dr. Edward Ahenakew in the Summer 1960 issue of the “Alberta Historical Review”

- An Account of the Frog Lake Massacre, as told to A.E. Peterson by George Stanley Mesunekwepan), in the Winter 1956 issue of the “Alberta Historical Review”

- Massacre Street (September 2010), by Paul William Zits

Leave a Reply