Back to The Klondike Gold Rush.

In the summer of 1897, the steamboats Excelsior and Portland arrived in San Francisco and Seattle, respectively, bringing news of the Klondike Gold Rush to the Outside world. The news spread like wildfire throughout the west coast. Almost immediately, thousands of would-be prospectors from all walks of life quit their jobs, outfitted themselves with provisions and equipment, and purchased steamship tickets north, bound for Dawson City. This mass exodus was known as the Klondike Stampede.

The Dawson Trails

Participants in the Stampede of 1897/98 were known as Stampeders. Throughout the autumn of 1897 and the winter of ’97/’98, Stampeders converged on Dawson City, a boomtown situated at the mouth of the Klondike River, from many different directions. The routes these men and women took on their ways to the Klondike are sometimes referred to as the Dawson Trails.

The Bennett-Dawson Trail

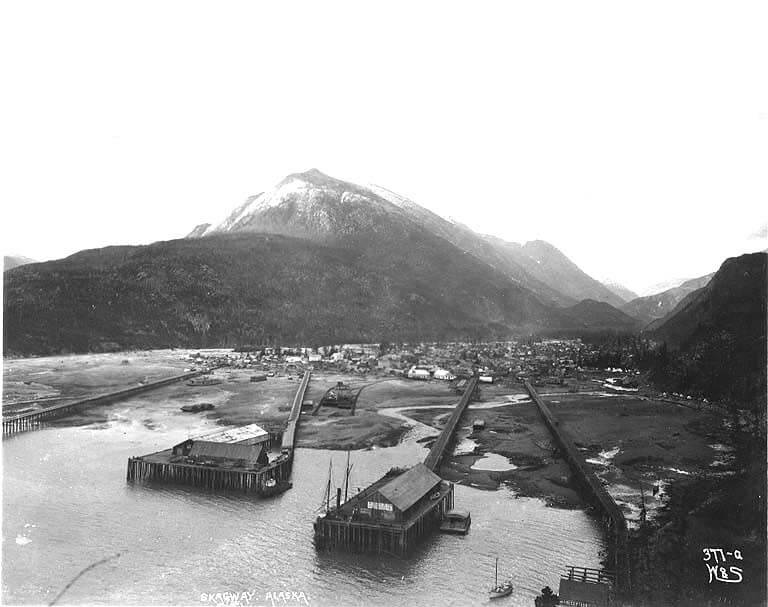

Perhaps the most famous of all the Dawson Trails is the route known as the Bennett-Dawson Trail. Stampeders reached this trail by taking steamboats north up the coast of British Columbia, up the Alaskan Panhandle, and up the Lynn Canal, an inlet which penetrates the Alaskan mainland about 540 km southeast of the Klondike goldfields. At the end of Lynn Canal, Stampeders would either disembark at Skagway or Dyea, two boomtown port towns separated by a distance of about 5 km.

Prospectors who landed at Skagway took the White Pass over the Coast Mountains, the range which separates the west coast from the interior. The White Pass was so rough on pack horses that it came to be known as the Dead Horse Trail. Stampeders who disembarked at Dyea, however, took the Chilkoot Pass over the mountains. The Chilkoot Pass was an ancient route that had long since been used by Tlingit traders, who annually crossed over to the interior to trade with the Tagish of the western interior. Both the White and Chilkoot Passes ultimately led to the same location: Lake Bennett. The route from Bennett to the Klondike is known as the Bennett-Dawson Trail.

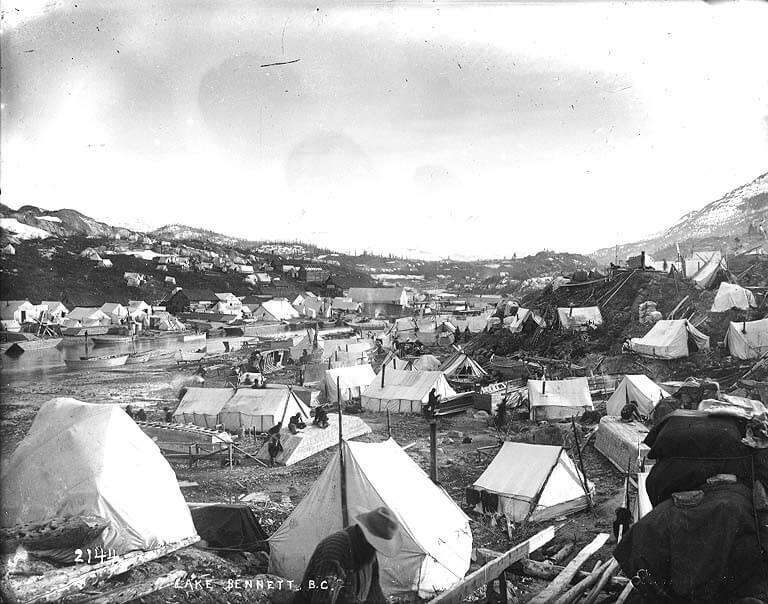

Throughout the fall and winter of 1897, thousands of prospectors set up camp on the shores of Lake Bennett. The temporary settlement that emerged was the greatest tent city in the world. In order to proceed down the Bennett-Dawson Trail, the Stampeders would have to build boats. And so, in the fall and winter of 1897, thousands of men set about constructing watercraft from the surrounding spruce trees.

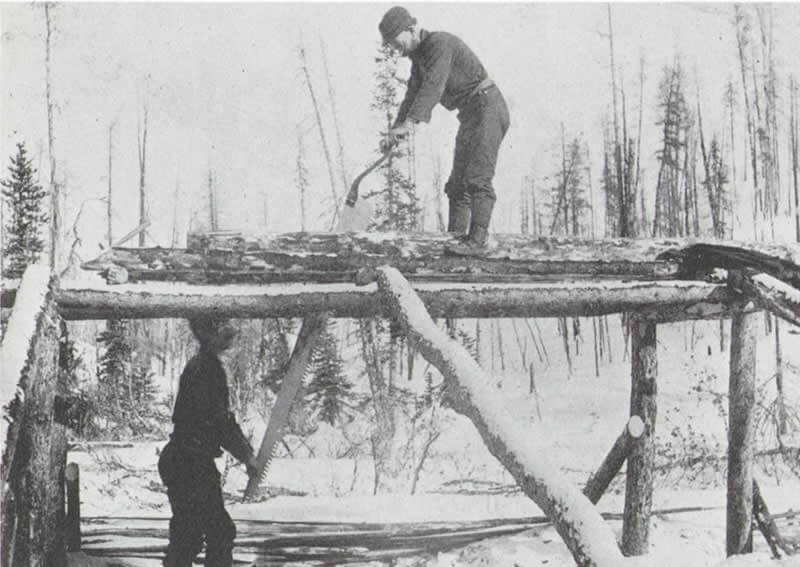

First, the Stampeders would fell the trees with axes. After that, they would cut the branches and strip the bark from the main trunk. Then, in order to rip the green wood into usable planks, two men would have to saw down the grain using a massive two-man whipsaw. This process was both physically exhausting and extremely frustrating, as it required an immaculate degree of cooperation in order to run smoothly. Many partners who had weathered the nightmarish steamboat ride north and had conquered the grueling mountain passes together became bitter enemies in the sawpits of Lake Bennett. Fortunately, even the most heated of disputes were resolved by Mountie Sam Steele, who ruled over the tent town with an iron fist.

The North West Mounted Police, under the leadership of Sam Steele, inspected each and every boat that winter. If they concluded that the boat was safe and sound, they painted a serial number on its bow, indicating that the watercraft was ready for the rapids of the Yukon River. If they decided that the boat was unfit for river conditions, however, the Mounties gave the unfortunate Stampeders advice on how to improve their craft’s construction.

When spring came and the river ice melted, a ragtag fleet of more than 7,000 boats set off across Lake Bennett. The Stampeders rowed or poled their way to Caribou Crossing, a traditional Tagish/Tlingit fishing and hunting village situated at the northeast corner of Lake Bennett, at the site of present-day Carcross, YT. From there, they disembarked and portaged the short distance east to the adjacent Tagish Lake.

The Stampeders paddled up Tagish Lake and into Marsh Lake, which was connected to the former by a natural canal. At the end of Marsh Lake, the Stampeders entered the Yukon River.

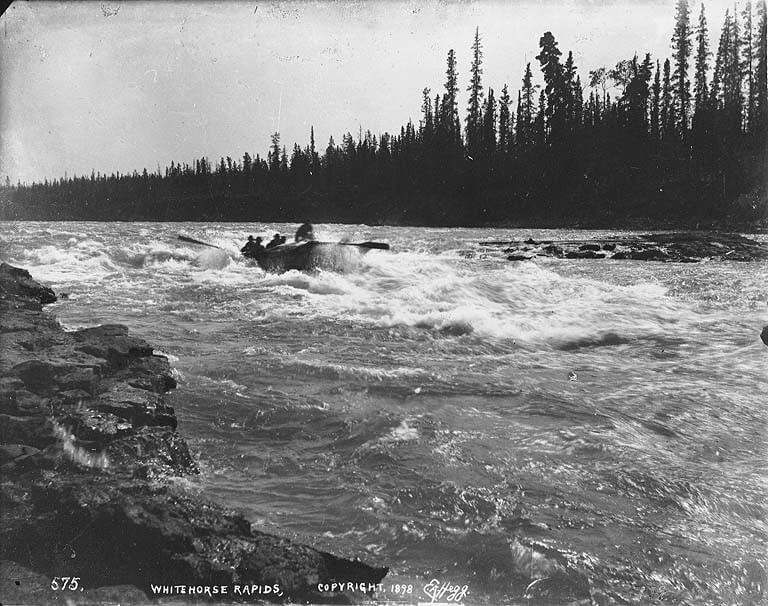

The first obstacles that Stampeders had to overcome on the Yukon River were the Miles Canyon and White Horse Rapids. The first set of rapids, the Miles Canyon Rapids, was a labyrinth of whirlpools and jutting rocks, lined by sheer hundred-foot walls of volcanic rock. Many considered it a warm-up for the treacherous White Horse Rapids beyond. The White Horse Rapids, located at the site of the present day capital of the Yukon (Whitehorse, YT) were so named because their frothy current resembled the mane of a galloping white horse. The North West Mounted Police considered the rapids so dangerous that they only allowed boats to travel down them if they were captained by competent pilots. They also prohibited women and children from hazarding the rapids, and required them to make the journey along the shores of that dangerous stretch of the river on foot. Due in part to the Mounties’ stipulations, only ten men, out of the thousands who traversed it, died in the rapids.

After conquering the Miles Canyon and White Horse Rapids, Stampeders continued down the Yukon River into Lake Laberge. Years later, Lake Laberge would feature in Jack London’s novel, “The Call of the Wild,” and Robert Service’s poem, “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” The prospectors took their boats over Lake Lebarge and into the Yukon River on the other side. They continued down the river for some time. Eventually, they came to the site of an abandoned cabin, trading post, and coal mine once occupied by George Carmack, one of the men to first discover gold in the Klondike. These log buildings were roughly located on the site of what is now Carmacks, YT. Carmack’s abandoned settlement served as a herald for the Five Finger Rapids beyond, the last major obstacle of the Bennett-Dawson Trail.

The Five Finger Rapids earned their name from the four rocky islands in their middle, which divide the river into five watery fingers stretching towards the Klondike. Of the five fingers, only the one on the far right, the easternmost finger, was navigable. Although the Five Finger Rapids looked formidable, they proved to be the easiest of the three rapids on the Yukon River. Like Lake Lebarge, these rapids also feature prominently in Klondike literature.

Some distance beyond the Five Finger Rapids, the Stampeders came to Fort Selkirk, an old Hudson’s Bay Company trading post which had, in 1852, been razed by Tlingit warriors. Beyond Fort Selkirk was the ghost town of Ogilvie, a relic of the short-lived Sixtymile Gold Rush named after William Ogilvie, the Dominion of Canada’s Yukon representative. And downriver from Ogilivie, at the mouth of the Klondike River, was the Stampeders’ final destination: Dawson City and the Klondike goldfields beyond.

The St. Michael Trail

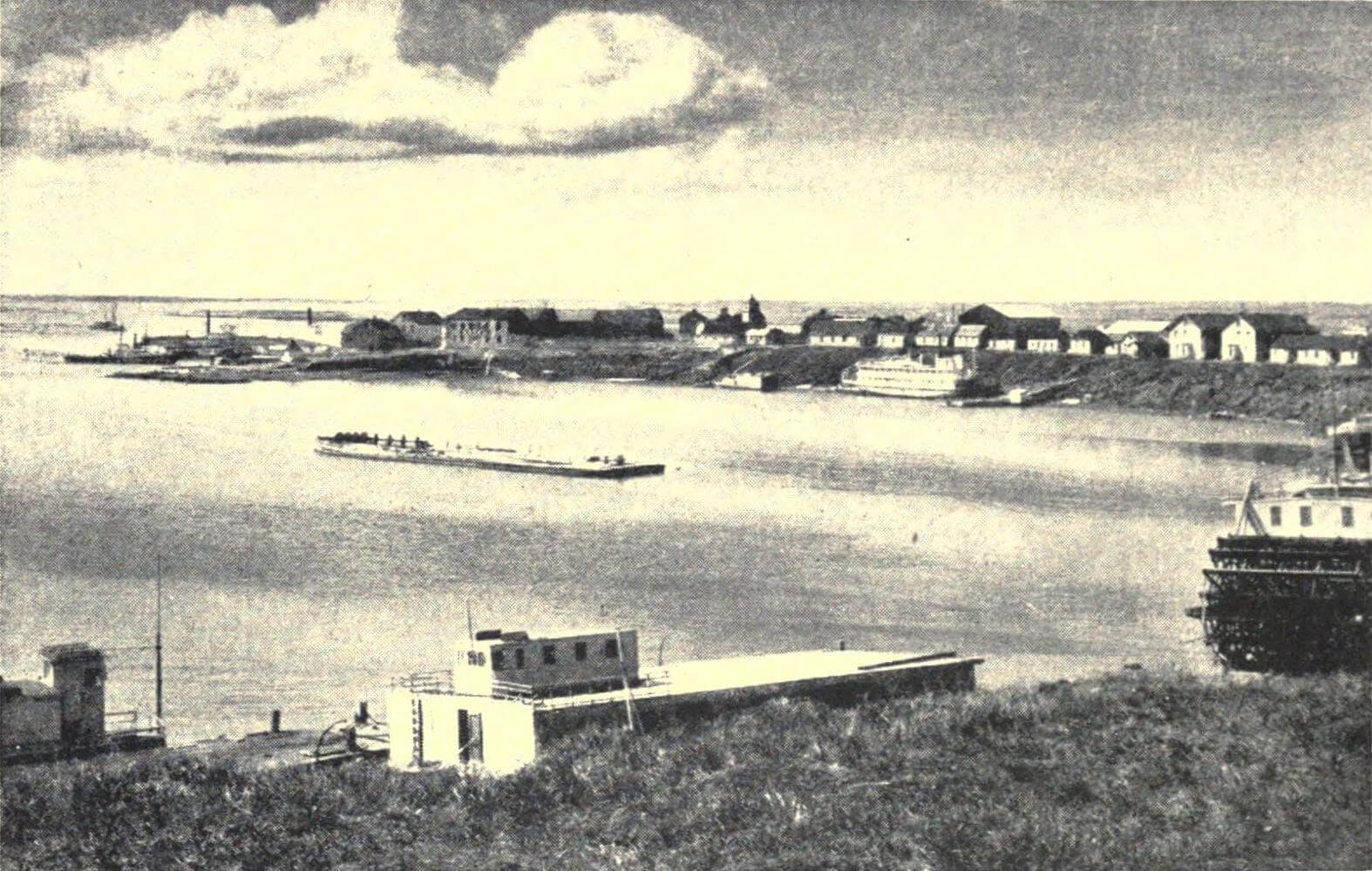

Another of the routes to Dawson and the Klondike was the St. Michael Trail. Also known as the ‘Rich Man’s Route’, this path was one used by some of the more affluent Stampeders. Like the Bennett-Dawson Trail, the St. Michael Trail began as a steamship voyage north up the Pacific northwest. However, instead of travelling up Lynn Canal, Stampeders who took this route traveled by steamboat all the way north to Unalaska, at the head of the Aleutian Islands. Then they traveled further north to St. Michael, Alaska, at the mouth of the Klondike River. Upon reaching St. Michael, Stampeders continued by steamer up the Yukon River. After stopping for fuel at the dying boomtown of Circle City, Alaska, the prospectors crossed into Canada and reached Dawson City.

In theory, a Stampeder could travel this route entirely by steamboat without hiking an inch of trail. However, in reality, many a steamship en route to the Klondike on the St. Michael Trail became trapped mid river in the fall, when the river froze. Many Stampeders who were trapped in this way continued up the frozen Yukon River to the Klondike on dogsled. Others traveled by foot to Circle City, where they stayed the winter.

All-American Routes

A number of American Stampeders who wished to avoid paying duty on their outfits upon crossing into Canada elected to take one of three so-called ‘All American Routes’ to the Klondike. Most of these All-American Routes began at one of three points on the Bay of-Alaska: 1) the head of Cook Inlet (at present-day Anchorage, Alaska); 2) Prince William Sound, at the base of the Valdez Glacier; 3) Yakutat Bay, at the base of the Malaspina Glacier.

Cook Inlet

The Cook Inlet Route, the westernmost of the All-American Routes, began at the head of Cook Inlet, at the mouth of the Matanuska Valley and the site of present-day Anchorage, Alaska. The trail led up the Matanuska Valley and over the Coast Mountains to the Tanana River. From there, Stampeders traveled down the Tanana to the Yukon River, then up the Yukon River to Dawson and the Klondike goldfields.

One of the men to take this route was an American soldier, Liutenant J.C. Castner of the 4th Infantry, who led a military detachment from the Pacific coast to the Tanana River. Castner wrote, “my men often said it would be impossible to make others understand what we suffered those days. No tongue or pen could do the case justice.”

Prince William Sound

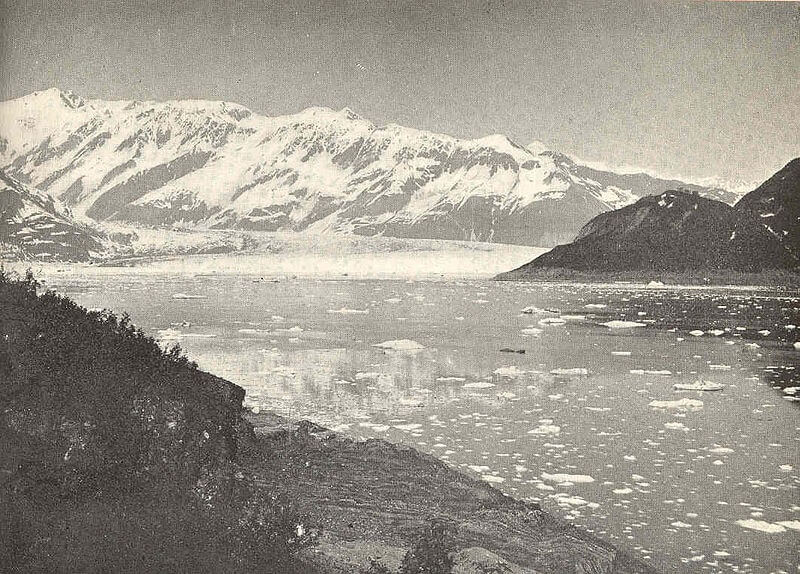

In the fall and winter of 1878/79, about 3,500 Stampeders disembarked at the Prince William Sound at the site of present-day Port Valdez, Alaska, bound for the Klondike. Before them was the massive Valdez Glacier. Prospective prospectors who chose this route had to haul their supplies over 300 yards of sand and six miles of snow to reach the base of the glacier. Then, they ascended the icy monolith, hoisting their sleds up with pulleys.

Upon reaching the windy, frozen summit of the Valdez Glacier, Stampeders made their slow and painful way over the ice field, picking their way through a minefield of deadly crevasses. They did most of their travelling at night, when the ice was solid enough to bear their weight. In the day, when they weren’t trying to sleep, the sun reflected off the snow and ice, causing many prospectors to go snow blind. Due to the glacier conditions, Stampeders were unable to thoroughly cook their food, and many survived their journey over the Valdez Glacier by subsisting on half-frozen, half-cooked meals. Others suffered from malnutrition and developed scurvy. Some died. In these harsh conditions, many prospecting parties split up.

The Valdez Glacier, despite bitterly cold temperatures, was much easier to travel over during the winter months. In the spring, the glacier began to melt, resulting in countless avalanches which buried many a Stampeder. In the summer, the glacier was all but impassable, and prospectors unlucky enough to be caught on it at that time found themselves trapped, unable to travel ahead or turn back. To make matters worse, the warm coastal wind mixed with the ice of the glacier to produce an unearthly fog which enshrouded the trapped Stampeders.

Those prospectors who managed to make it over the ice field and over the other side into the interior were faced with another obstacle: the Klutina River. A significant stretch of the Klutina was comprised of dangerous rapids, and nearly one man in four who attempted to navigate it lost his boat and his outfit.

Those who managed to survive the Klutina River drifted downriver into the Copper River, the realm of the warlike Ahtna Indians who had fiercely resisted Russian occupation throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Some Stampeders chose to stay and prospect on the Copper. Others traveled inland upriver, and then made the portage journey overland to the Tanana River. From there, they traveled down to the Yukon River, then upriver to Dawson City.

One of the stranger stories to come out of the Prince William Sound All-American Route is the tale of the Sasquatch-like Valdez Glacier demon. In the winter of 1898/99, a Second US Infantry captain named W.R. Abercrombie was stationed at Prince William Sound with the order to explore the Copper River area and report to the War Department with his findings. That winter, Abercrombie came across a Stampeders suffering from snow-blindness, scurvy, and frostbite. Abercrombie wrote in his journal:

I noticed in talking to these people that over seventy per cent of them were more or less mentally deranged. My attention was first directed to this fact by their reference to a “glacial demon”. One big, rawboned Swede, in particular, described to me how this demon had strangled his son on the glacier, his story being that he had just started from Twelve-Mile Plant (a small collection of huts just across the Coast Range of Mountains from Valdez) with his son to go to the coast in company with some other prospectors. When halfway up the summit of the glacier, his son, who was ahead of him hauling a sled, while he was behind pushing, called to him, saying that the demon had attacked him and had his arms around his neck. The father ran to the son’s assistance, but as he described it, his son being very strong, soon drove the demon away and they passed on their way up toward the summit of Valdez Glacier. The weather was very cold and the wind blowing very hard, so that it made traveling very difficult in passing over the ice between the huge crevasses through which it was necessary to pick their way to gain the summit. While in the thickest of these crevasses, the demon again appeared. He was said to be a small, heavy-built man and very active. He again sprang on the son’s shoulders, this time with such a grasp that, although the father did all he could to release him, the demon finally strangled the son to death. The old man then put the son on a sled and brought him down to Twelve-Mile camp, where the other prospectors helped bury him.

During the recital of this tale the old man’s eyes would blaze and he would go through all the actions to illustrate just how he fought off this imaginary demon. When I heard this story there were ten or twelve other men in the cabin and at that time it would not have been safe to dispute the theory of the existence of this demon on the Valdez Glacier, as every man there firmly believed it to be a reality.

Yakutat Bay

The Yakutat Bay All-American Route began on the Yakutat Bay, at the base of the Malaspina Glacier near the southern border of the Yukon. Of all the All-American Routes, this one was the most perilous and the least traveled. In theory, this route led across the Malaspina Glacier, overland to the Tanana River, down the Tanana and up the Yukon to the Klondike. Few men were able to survive this route. Fewer still were able to use it to reach the Klondike goldfields.

One of the best records of this route was set down by Arthur Arnold Dietz, a New Yorker. Dietz, the leader among a nineteen-man prospecting party, arrived at Yakutat Bay in April, 1898.

Slowly, Dietz’ team made their way over the ocean of ice that was the Malaspina Glacier. They were constantly beset by howling, icy winds which were so loud that they effectively prevented the party from engaging in any kind of conversation. According to Dietz, for three months the team “resembled a party of deaf mutes.” They battled snow-blindness and malnutrition, which drove several members of the party to insanity. Like the Valdez Glacier, the vast Malaspina was pocked with deep, deadly crevasses, and several team members- dogs, sleds, and all- disappeared into these seemingly bottomless chasms.

When the party finally reached the end of the Malaspina and entered the taiga forest on the other side, they were a fraction of their initial number. The haggard Stampeders pushed on overland through the forest towards the Tanana. In September, the prospectors stopped to build log cabins in which they hoped to weather the sub-arctic winter. During that winter, one of their members died of fever. Three more decided to brave the winter conditions and push on towards the Tanana by themselves. They were never seen again.

When spring came, the remaining Stampeders sunk a shaft to bedrock right there, on the shores of the Tanana River. When they found nothing but dirt, three of them decided to turn around and go prospecting at the base of the mountains. There, they were buried in an avalanche.

The remaining prospectors decided to travel down the Tanana River on foot. One the way, one of them died of scurvy. Delirious, the Stampeders ended up turned around and traveled back the way they had come. When they arrived at the Malaspina Glacier, they decided to traverse it again.

On the glacier, one of the prospectors died from a horrific case of frostbite. The rest of the party ran out of food. In order to survive, they slaughtered their sled dogs and ate the meat raw.

Finally, seven survivors reached the end of the Malaspina Glacier and came to the edge of the Pacific Ocean. There on the beach they rolled up into their sleeping bags. When they were discovered by American sailors, only four of them were still alive. Of the four survivors, two had become near-sighted, while the other two were completely blind due to the effects of the glare on the Malspina.

All-Canadian Routes

Like their American counterparts who took the All-American Routes to the Klondike in the hopes of avoiding Canadian customs officers, a number of Canadian Stampeders decided to take all-Canadian trails to Dawson in order to avoid American customs officers at Skagway and Dyea. These All-Canadian Routes included: 1) the Ashcroft Trail, which ran through the interior of British Columbia; 2) the Stikine Trail;

Ashcroft Trail

The Ashcroft Trail began at the town of Ashcroft, a small BC town that could be reached from Vancouver by way of the Thompson River. The trail passed through the Fraser Valley and Cariboo Country, the sites of two bygone Canadian gold rushes. From there, it followed slash line of the Collins Overland Telegraph. The Collins Overland Telegraph was a 3 million dollar project which involved linking linking San Francisco, USA, with Moscow, Russia, by way of an enormous telegraph line stretching over the Bering Sea. Although the project had been abandoned in 1867, a slash line through the forest extended from Ashcroft to Teslin Lake, located on what is now the BC/Yukon border. Teslin Lake was also the headwaters of the Yukon River, and Stampeders who made it there could travel down the river by boat to Dawson.

At least 1,500 Stampeders attempted to reach Dawson by way of the Ashcroft Trail. Only a handful of them arrived at their destination. The southern stretch of the trail passed through the dark, misty jungle of what is now the Great Bear Rainforest. The northern stretch of the trail was a swampy nightmare. It was almost completely bereft of horse fodder, and many horses died from starvation, or from eating poisonous weeds. The trail was home to massive swarms of mosquitoes and huge black flies which hounded the Stampeders and their mounts at every turn. All along the route, Stampeders carved messages of despair into tree trunks. One message read:

There is a land of pure delight

Where grass grows belly-high;

Where horses don’t sink out of sight;

We’ll reach it by and by.

Another said:

This is the grave the poor man fills,

After he died from fever and chills,

Caught while tramping the Stikine Hills,

Leaving his wife to pay the bills….

For some, the trail proved to be too much. One man hanged himself from the cross-tree of his tent, leaving behind the message: “Bury me here, where I failed.”

Stikine Trail

Another of the All-Canadian Routes was the Stikine Trail. The first leg of this journey was a steamboat ride up the west coast to the mouth of the Stikine River, in northern British Columbia. It followed the Stikine River to the town of Glenora, the site of an old Hudson’s Bay Company fort which developed into a town during the Cassiar Gold Rush. From there, it joined the Ashcroft Trail.

Edmonton Trail

Another All-Canadian Route to Dawson and the Klondike was the Edmonton Trail. As its name suggests, this trail began at Edmonton, Alberta. Its name also suggests one well-travelled route from Edmonton to Dawson. In fact, there were many routes, and all of them were terrible.

Most of these routes led northwest to the Peace River Country. Some of them went by way of the Athabasca River, down the Lesser Slave rivers, and over Lesser Slave Lake. Other trails took Stampeders overland, through Fort Assiniboine. Others still took Stampeders further west, from Lac St. Anne to Whitecourt to Grande Prairie to Fort St. John, BC.

By the time they arrived at the Peace River, most Stampeders were disheartened and decided to turn back. The few that pushed forward blazed their own trails.

The prospectors who had traveled to traveled to Fort St. John traveled up the Peace River into Stikine Country. From there, they portaged west to the Dease River, traveled downriver to Fort Liard, an ancient North West Company – turned HBC post. From there, Stampeders traveled down the perilous Liard River, with its Rapids of the Drowned, to the Pelly, down the Pelly River to the Yukon, and down the Yukon to Dawson.

Other Stampeders traveled down the Peace River to Lake Athabasca, down the Slave River to Great Slave Lake, and across the massive lake to the Mackenzie River. From there, they journey down the Mackenzie to the Liard River, where their trail joined that of those who had traveled by way of Fort St. John.

Many more Stampeders who reached the Peace River portaged overland to the Fort Nelson River to the northwest. They traveled down the river, past Fort Nelson, to the Liard River, where their trail joined up with that of the other Edmonton Trail Stampeders. From there, they journeyed downriver to the Pelly, down the Pelly to the Yukon, and down the Yukon to Dawson City and the Klondike goldfields.

Back to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 4: The Stampede

Forward to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 6: Dawson City

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

Leave a Reply