Back to The Klondike Gold Rush.

By autumn 1897, the Klondike Gold Rush was in full swing. Throughout the fall of 1897 and the winter and spring of 1898, thousands of Stampeders (as Klondike gold seekers were known) converged on Dawson City and the Klondike from many different directions. Some took the so-called “Rich Man’s Route”, travelling by steamer to St. Michael, Alaska, on the Bering Sea, then up the Yukon River to Dawson City. Others took the perilous all-American routes over crevasse-ridden glaciers, or the grueling all-Canadian route over thousands of miles of sub-arctic swamp. Many more traveled by steamer up the Lynn Canal to Skagway or Dyea, scaled the Coast Mountains by way of either the White or the Chilkoot Pass, and took the watery Bennett-Dawson Trail down the Yukon River to Dawson City. All set out with the hopes of striking it rich. Few reached Dawson, and fewer still found the gold they had initially set out to find.

Arrival

As soon as the spring ice melted, dozens of rough, hand-hewn boats drifted into Dawson City. The men and women aboard them were Stampeders who had outdistanced their counterparts- most of whom had wintered at Lake Bennett- and had been forced, due to freeze-up, to spend the winter along the shores of the Yukon River. They told the Sourdoughs at Dawson of the massive armada behind them which would arrive at Dawson any day.

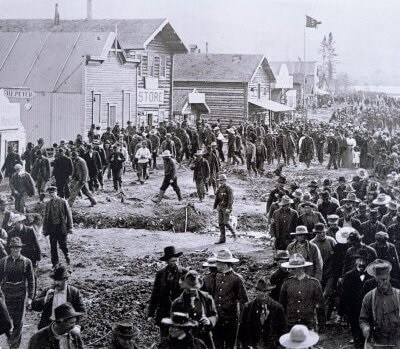

Sure enough, in June, 1898, thousands of boats rounded the river bend and disgorged their cargo on the shores of Dawson City and the surrounding riverbank. At the same time, steamboats filled with Stampeders who had taken the Rich Man’s Route from St. Michael, Alaska, poured into Dawson City from upriver. In the space of a month, Dawson grew from a rough northern boomtown peopled by so-called ‘Sourdoughs’ long-accustomed to the rigors of the subarctic to a veritable hive of humanity composed of Stampeders of all ethnicities, nationalities, and backgrounds. In no time, the river valley resounded with the sounds of saws and hammers as Dawson grew into the largest Canadian town west of Winnipeg.

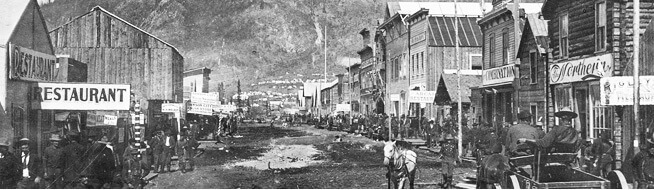

Many Stampeders immediately set about erecting shops in which they would sell merchandise they had hauled all the way over the Dawson trails. Several men had brought broods of hens to Dawson City and began to sell their eggs at exorbitant prices. One man who managed to haul a dairy cow all the way to the Klondike sold fresh milk at thirty dollars a gallon. One Italian New Yorker named Signor R.J. Gandolfo set up a fruit stand at which he sold, among other things, tomatoes at five dollars a pound (to put this in perspective, back in New York Gandolfo sold two baskets of tomatoes for a nickel). A newspaper boy who had lugged Seattle newspapers to the Klondike sold his wares to news-hungry Sourdoughs for incredible prices (for example, one Klondiker purchased an old newspaper for $59 in gold dust). Others who had hauled printing presses piece by piece over the mountain passes started up their own Klondike newspapers. By summer, Dawson City boasted two newspapers (The Klondike Nugget and the Midnight Sun), two banks, five churches, and a telephone service.

Other Stampeders, upon arriving in Dawson City, searched for friends with whom they had been separated somewhere along the Dawson trails. According to Arthur Christian Newton Treadgold, an Oxford tutor who had abandoned academia for the Klondike: “The main street is nearly always crowded with men trying to find one another for… it is a hard matter to find a man in Dawson and much time is wasted thereby. When you find your man the two of you sit on the edge of the sidewalk (raised a foot above the road for cleanliness) and talk. This is a picturesque sight, for men are of all nations in all kinds of quaint garments, standing or sitting in business on the main street.”

Interestingly, most of the Stampeders who arrived at Dawson in the summer of 1898 never went out into the Klondike watershed to search for gold. In the words of historian and writer Pierre Berton, “it was as if the vitality that had carried these men across the passes and down the rivers, shouting, singing, bickering, and slaving, had been sapped after ten months of struggle.” For these men and women fresh from the trail, the prospect of spending another two seasons doing the hard manual labour necessary to locate and extract gold was exhausting. Many of these Stampeders either sold their outfits or landed a job and worked just long enough to earn themselves a steamship ticket back to the Outside. By the end of the summer, nearly two thirds of the Stampeders who had arrived at Dawson City that June had left for home empty-handed.

A Year in the North

Those who chose to remain in Dawson and the Yukon that year bore witness to the end of a brief but fiery era. From the summer of 1898 until the summer of 1899, a number of prominent northerners who had made indelible marks upon Yukon and Alaskan history met their ends in one way or another.

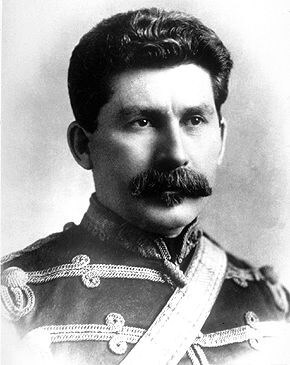

One such man was fifty-four-year-old Yukon Commissioner James Morrow Walsh. Before he had even set foot in the Yukon, Walsh was already a man of considerable repute. He, along with only a handful of others, was one of the original officers of the North West Mounted Police. He had ridden west with the Force during the famous trek of 1874. He had served as the first Commissioner of Fort Walsh, in the Cypress Hills, which was named after him. He had been the first white man to ride into the camp of Sioux Chief Sitting Bull and leave with both his scalp and his life (excepting, perhaps, Pony Express riders Kootenai Brown and Joe Martin). In fact, he had even made friends with the fearsome war chief and convinced him and his Sioux to abide by Canadian law while north of the border (the Sioux had fled to Canada following the Battle of the Little Bighorn, fearing retribution from the U.S. Army). Unfortunately, Walsh’s experience in the Klondike marred his otherwise spotless reputation.

In the summer of 1898, Walsh, who had served as the first Commissioner of the newly-established Yukon Territory since August 1897, was indicted for political graft. Walsh’s cook, a man named Louis Carbeno, testified under oath that he was employed only upon agreeing to give three quarters of any gold he found working a claim to either Walsh or Walsh’s brother Philip. Although Walsh’s trial was inconclusive, he resigned nevertheless. He was succeeded by William Ogilvie, a Canadian surveyor who had lived in the Yukon since the days of the Fortymile Gold Rush. Walsh retired to Brockville, Ontario, where he resided until his death in 1905.

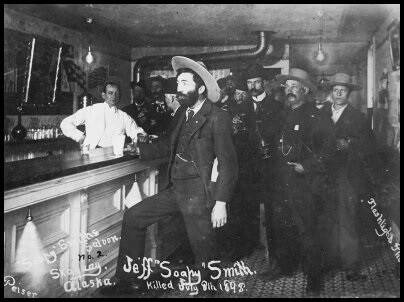

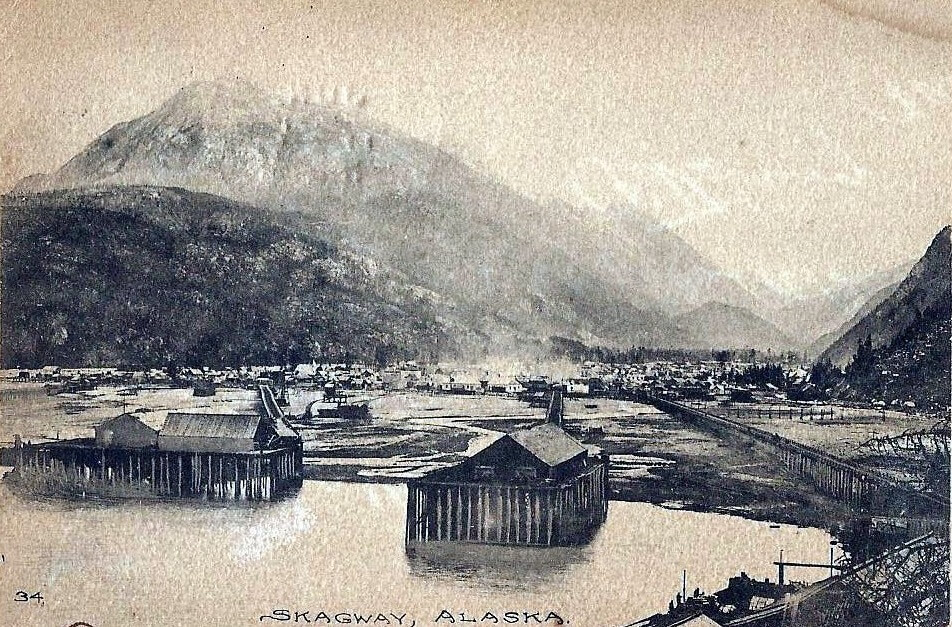

Another legendary figure of the Klondike Gold Rush to meet his end in the summer of 1898 was Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith. Soapy Smith was a smooth-talking con-man who had built himself a criminal empire in Denver, Colorado. Once the Klondike Stampede was underway, Smith took his scheming to the town of Skagway, Alaska, at the head of the White Pass, where he built up another little empire. In no time, Smith was the dictator of Skagway in all but name, and his gang members extolled an illicit tax on any Stampeder unfortunate enough to let his guard down while in town.

In July, 1898, one of Smith’s men stole a $2,800 poke from a prospector named John Douglas Stewart, who was returning from the Klondike by way of the Bennett-Dawson Trail and the White Pass. There was nothing particularly unusual about this incident; prospectors returning from the goldfields were routinely robbed by Smith’s men in Skagway. However, Stewart would have none of it; the prospector was very vocal about the crime, and soon a gang of vigilantes emerged from the Skagway woodwork and demanded that Smith return the poke.

When Smith refused to cooperate, the vigilantes held a meeting on Juneau Wharf, one of the Skagway docks. When Smith received word of the meeting, he headed to the dock armed with a Winchester rifle and a Colt revolver. Smith ordered the vigilantes to scatter. Although some obeyed, a man named Frank H. Reid stood his ground. Smith and Reid engaged in a brief brawl which culminated in both of them being shot. Smith died instantly with a bullet in his heart. His last words were, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot!” Reid received a bullet in his lower abdomen and groin, and survived for twelve days before expiring. Following Smith’s death, most of his gang members fled town.

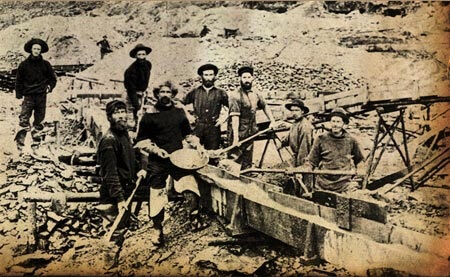

When fall came, a small number of Stampeders who remained in Dawson City, Yukon, took to the Klondike to search for gold. Some Cheechakos, newcomers to the north, decided to eschew the claims that girded the creeks and dig shafts in the hills. Sourdoughs who had prospected for their entire lives scoffed at the greenhorns, who obviously had no idea what they were doing. In their minds, any prospector with even a lick of experience would know to avoid the hills, as gold was heavy and had a tendency to find its way to the lowest parts of the land, which were the stream beds. However, neither Cheechako nor Sourdough knew that the hills overlooking the Klondike were lined with ancient stream beds that had long since ran dry. The Cheechakos who sunk shafts in the hills stumbled upon a particularly rich vein of gold and returned home fantastically wealthy. Because of their successes, one of the hills on which they dug was named Cheechako Hill.

Fall turned to winter, and the soil froze solid. Every night, prospectors lit fires inside their mines, and every morning they cleared out the ashes and dug through the thawed earth. Picks fell, windlasses turned, and the dump piles which punctuated the claims along the Klondike rose higher and higher.

The winter of 1898/99 was arguably the golden era of the Dawson City, an era characterized by extravagance. The city’s population was at its height, and its saloons, dance halls and game rooms were perpetually packed with prospectors, adventurers, bartenders, gamblers, businessmen, and entertainers who hailed from all walks of life. Sourdoughs who had struck it rich- like ‘Swiftwater’ Bill Gates (no relation to the present-day billionaire of the same name whose grandfather, William Henry Gates I, happened to be one of the Stampeders in Dawson City that year), ‘Big Alex’ McDonald, and Charley Anderson, ‘The Lucky Swede’- strutted about town, lavishing outrageous gifts- like hundreds of fried eggs (a luxury in the Klondike) and bathtubs filled with hugely-overpriced champagne- on dance hall girls they fancied. Gold and whisky flowed like water. That winter, Dawson saw another miniature gold rush as well as a massive fire which all but wiped out Main Street.

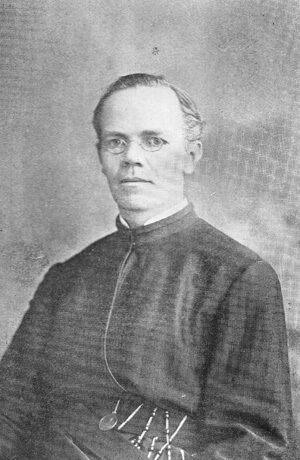

That winter, another legendary Klondike figure met his end. His name was Father William Judge, and he was a Jesuit priest. Judge, who had served the Catholic Church in Alaska since 1890, made his way to the Klondike following George Carmack’s discovery in August 1896. Unlike almost everyone else who flocked to the Klondike during the Stampede, however, Judge was never looking to strike it rich; he was truly pious, and hoped to serve God by ministering to the northern gold seekers, whom he described as “men running away from civilization as it advanced westward- until now they have no farther to go and so have to stop.” Upon arriving in the rapidly-growing town of Dawson, Judge set about constructing a church, a rectory, and the town’s first hospital, St. Mary’s Hospital. At the hospital, he cared for Stampeders afflicted with maladies typical of the Klondike Gold Rush, like frostbite, scurvy, typhoid, dysentery, and malaria. One such Stampeder whom Judge nursed back to health was future fiction writer Jack London, who had come down with a bad case of scurvy in the winter of 1897/98. As a Jesuit, Judge had taken a vow of poverty, chastity, and obedience. If any prospectors tried to compensate him for his invaluable work, he invested the money in blankets and medicine for his hospital. On Christmas Day, 1897, Judge politely refused to accept a Christmas gift consisting of a custom-tailored suit, sealskin coat, cap, and gloves, which a handful of grateful Klondikers had procured in the hopes of garbing the frail priest in something more substantial than the tattered black cassock he affected. Due to his immaculate character, the selfless Jesuit soon earned the epithet”the Saint of Dawson.”

Judge had no formal assistants, and performed almost every task himself. He built the church, rectory, and hospital with minimal help, and for the few volunteers who assisted him he cooked meals. He nursed and doctored all his patients himself, and when one of his patients died, he personally chipped his way through the permafrost with pick and shovel and buried him. He never turned a patient away, and even converted his own rectory into a hospice when the hospital became overcrowded. He was chronically overworked, and got very little sleep. In time, his exertions took their tole; in the winter of 1899, Judge came down with pneumonia, and on January 16, he died. In a grotesque twist of irony, the Klondike Sourdoughs interred Judge in a magnificent, thousand-dollar coffin- something which probably had the Saint of Dawson rolling in his grave.

Winter turned to spring, and the prospectors who had laboured all winter washed the pay dirt from their mines in sluice boxes, afterwards collecting the gold that settled in the ribs at the bottom. Most found themselves largely empty handed. Some, however, had made more than enough to pay for the steamboat tickets back home. A select few had struck it rich.

Summer came, and along with it, the White Pass Railway. Since May, 1898, labourers and engineers had worked on a narrow gauge railway line which was to connect Skagway, Alaska, with the Klondike goldfields. In July 1899, the railway reached Lake Bennett, Yukon, at the head of the Bennett-Dawson trail. Since the beginning of the Stampede, the Bennett-Dawson trail had been the most popular route to the Klondike, and the only routes to the Bennett-Dawson trailhead from the Pacific Ocean were the White and Chilkoot Passes. Until the White Pass Railway was built, the Chilkoot and White Passes were used with relatively equal frequency, and the feet of the passes both boasted sizable towns (Dyea and Skagway, respectively). However, when the White Pass Railway reached Lake Bennett, traffic on the Chilkoot slowed to a halt almost overnight, and the town of Dyea all but evaporated. Soon, almost all prospectors on their way to the Klondike traveled by way of the White Pass Railway. And thus two prominent icons of the Klondike Gold Rush, Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail, met their ends.

In midsummer, the citizens of Dawson City received rumors of a fresh strike in Nome, Alaska, on the coast of the Bering Sea. As had been the case in California, Fraser Canyon, the Cariboo, Cassiar, Fortymile, and Circle City, thousand of prospectors immediately abandoned Dawson and flooded towards the new diggings. The Klondikers were off an another Stampede. And as soon as it had began, the Klondike Gold Rush came to an end.

Legacy

In the end, about 100,000 people set off down the Dawson Trails during the Klondike Gold Rush. About 30-40,000 actually reached their destination. Only about 20,000 Stampeders, upon arriving in Dawson City, bothered to look for gold, and of those who did, only 4,000 found anything of significance. Of those 4,000, only a few hundred struck it rich, and of that number, only a scattering managed to hold onto it.

For many Stampeders who toiled on the mountain passes, braved the rapids of the Yukon River, and battled the bone-chilling temperatures of the sub-arctic winter, the reward at the end of the Dawson Trail was not gold but rather an indomitable character tempered in the fires of an experience they would never forget. In the words of Stampeder Walter Russell Curtin, “I had thirty-five cents in my pocket when I set foot in Alaska, but I gave that to a mission church at Dutch Harbor. I did not have so much when I left the country more than two years later… I made exactly nothing, but if I could turn time back I would do it over again for less than that.”

Back to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 5: Dawson Trails

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online book store:

Leave a Reply