Back to The Klondike Gold Rush.

In the summer of 1896, gold was discovered in the Klondike region of what is now Canada’s Yukon territory. When word of the find spread up and down the Yukon River, prospectors from all over the Canadian and American north abandoned their shacks for the new diggings. As was typical of northern Canadian gold rushes, a boom town sprouted almost overnight a short distance from the goldfields. This ramshackle community, situated at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers, would become the famous Dawson City.

Throughout the following fall and winter, prospectors staked claims along the Klondike creeks and sunk shafts to bedrock. When spring came, they washed the rubble from their mines in sluice boxes and collected the gold that accumulated at the bottom. Many had struck it rich.

In the summer of 1897, two steamboats arrived at Dawson City. The steamboats took on passengers and massive quantities of gold before heading to port towns on the Pacific Coast. From there, ex-prospectors who had made their fortunes on the Klondike boarded steamers bound for civilization. They would be the first heralds to bring news and tangible proof of the Klondike Gold Rush to the Outside world.

Excelsior and Portland

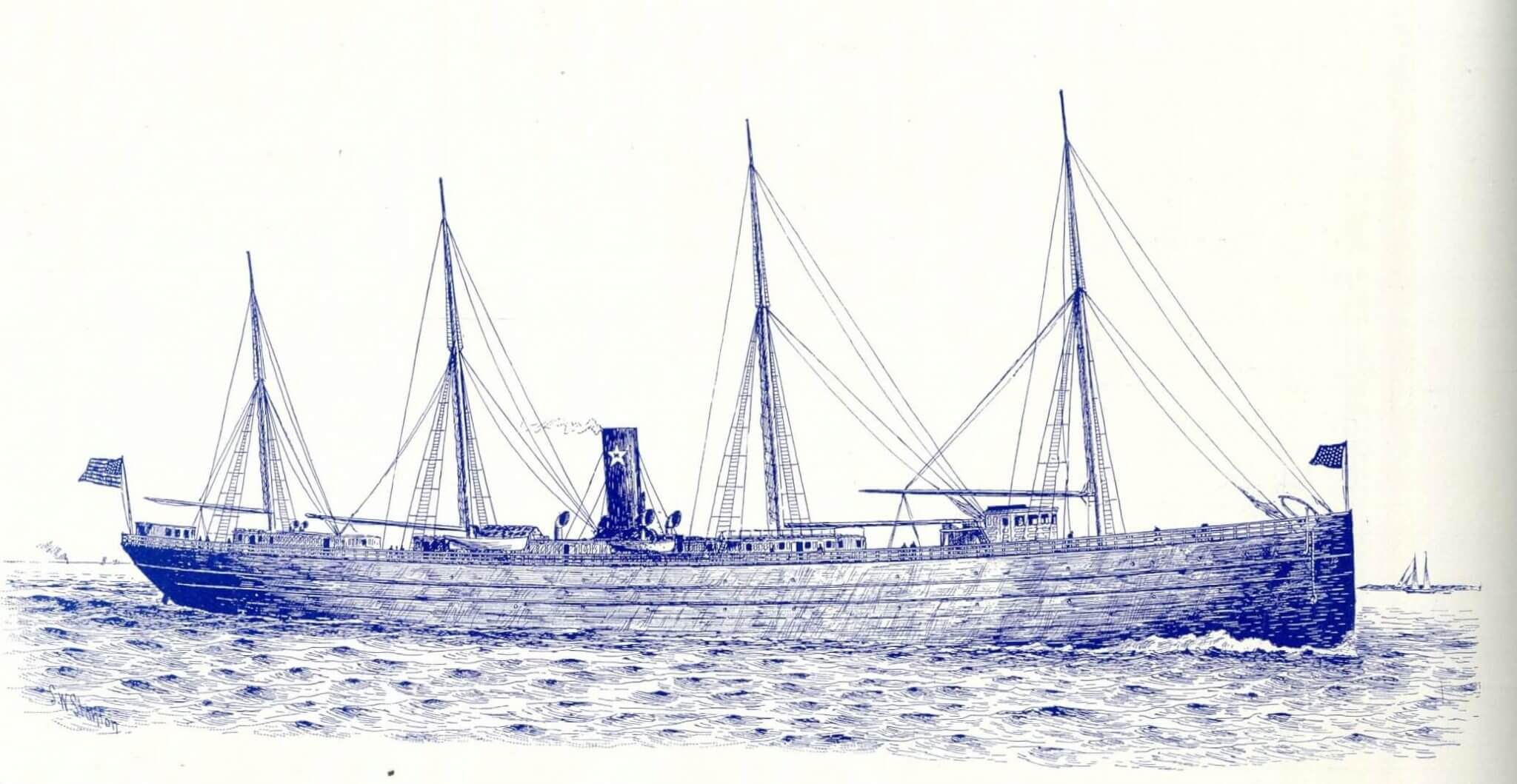

On July 14, 1897, a steamship called the Excelsior pulled into the San Francisco harbour. To the San Franciscans on the docks that day, the Excelsior- a rusty little ship with two blackened smokestacks- appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary. A few heads might have turned, however, when its passengers walked down the gangplank. The people who poured off the Excelsior were a gaunt, ragtag bunch clad in ragged work clothes and broad-brimmed hats. The men bore rough, unkempt beards, the women wore wild, tangled hair, and all had sun-burnt, wind-whipped faces resultant of at least one year in the Canadian north.

What really captured the attention of the San Franciscans that day, however, was the cargo the passengers hauled from the ship. Many- like former YMCA physical instructor Tom Lippy and his wife Salome- wrestled with extraordinarily heavy suitcases. Some lugged canvas sacks on the verge of tearing. Others dragged buckskin bags on the ground behind them, or hauled heavy tin cans using both hands. The strange site piqued the curiosity and imaginations of nearby locals. Soon, a growing throng of city residents began gather around the newcomers.

Some of the Excelsior passengers immediately made their way to the Selby Smelting Works on Montgomery Street. There, on the counters, they revealed their identities and the contents of their cargo to the curious onlookers; they were prospectors from the north, and they had brought with them countless pounds of raw northern gold.

The news spread like wildfire throughout the streets of San Francisco: a big strike had been made in Canada’s Yukon Valley. In no time, the news spread all throughout the West Coast. Soon, word was out that a second Yukon steamer called the Portland would arrive in Seattle any day. This one would be carrying even more gold than the Excelsior. Hoping to have the story before their competition, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sent a handful of reporters to intercept the Portland via tugboat before it reached the Port of Seattle. The journalists boarded the south-bound Portland on the Puget Sound, interviewed the miners on board, then returned to Seattle. What happened next was summarized in a front-page article written by these same reporters; the citizens of Seattle were greeted by these words on the front page of the July 17 paper: “At 3 o’clock this morning the steamer Portland from St. Michael for Seattle, passed up the Sound with more than a ton of solid gold aboard…”

Klondike Fever

In the summer of 1897, North America was ripe for a gold rush. The world was at peace and the United States had settled into a serious economic depression following the Panic of 1893. When the Excelsior and Portland slid into the ports of San Francisco and Seattle bearing dozens of prospectors and several metric tons of Klondike gold, the American West Coast, according to a New York Herald journalist, went “stark staring mad on gold.”

The gold fever that rippled through the West Coast in the summer of 1897 was nothing short of an epidemic. Newspaper men referred to this affliction which held the populace of the Pacific Northwest in such thrall as “Klondicitis”. Men and women from all walks of life immediately quit their jobs and bought steamer tickets for Alaska. Entire industries ground to a halt as employees ditched their work sites en masse for the Klondike. Soon, the Seattle Times was operating on a skeleton crew, San Francisco’s new cable cars were largely devoid of conductors, and the Seattle Police Department was severely undermanned. Even the Mayor of Seattle, William D. Wood, left his office for the Yukon. By July 24, 1,500 people had left Seattle for the Canadian north.

Newspapers aptly referred to this mass exodus as a “Stampede”. The name stuck, and prospectors bound for the Klondike were thereafter known as ‘Stampeders’. In the words of J.E. Fraser, one such Stampeder from San Francisco:

“The man who had a family to support who could not go was looked on with a sort of pity … the man who didn’t care to leave his business or for other trivial reasons, was looked on with contempt as a man without ambition who did not know enough to take advantage of a good thing when placed in his reach; but the man who could go, and would go, and was going to the Klondike, the man who could not be stopped from going, by any means short of a wire cable anchored to a mountain, was a hero. He was looked up to; he was envied by everybody; he was pointed out in the streets.”

Just as entire industries virtually evaporated in the summer of 1897 as their employees abandoned their work for the Klondike, so too did a number of businesses thrive. The transportation industry exploded as countless passengers purchased steamboat tickets north. Grocery and supply store owners who cleverly marketed their wares as ‘Klondike grade’ made fortunes selling outfits to prospectors-to-be. In fact, just about any product bearing the magic word ‘Klondike’ was likely to sell in those summer months. And as quickly as it had began in 1893, the economic depression that had prevailed for the last four years was no more.

Entrepreneurs and con-men alike took advantage of the situation. The former sold interesting (if impractical) inventions like ‘automatic’ gold pans, which rotated like the cylinders of phonographs, and sleds equipped with gasoline-powered motors to Stampeders. The latter peddled useless items like trail bikes and ‘tunnel-digging’ gophers to naive adventurers. According to Arthur Dietz, a New Yorker who was visiting Seattle at the time of the Klondike craze, “[Seattle was] more wicked than Sodom… the devil reigned supreme. It was a gigantic chaos of crime and the city government, as an institution, protected evil.”

Klondike fever quickly swept throughout the northern hemisphere, and further still to the rest of the world. By August, prospectors from as far away as New Zealand were making their way towards the Yukon.

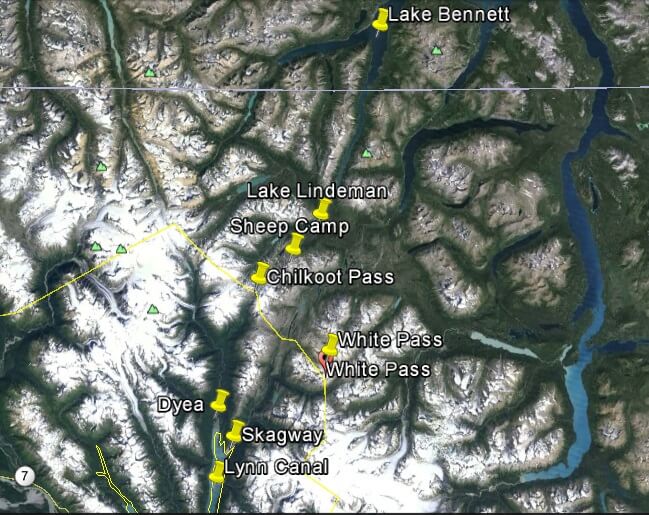

The Voyage North

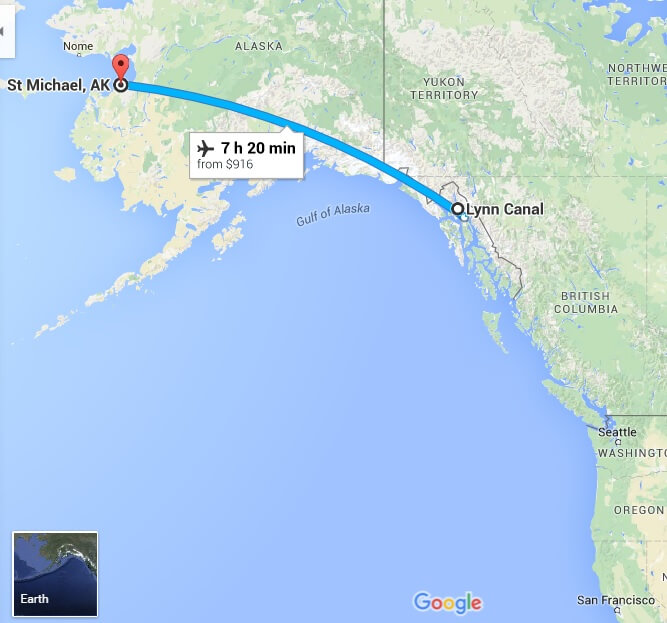

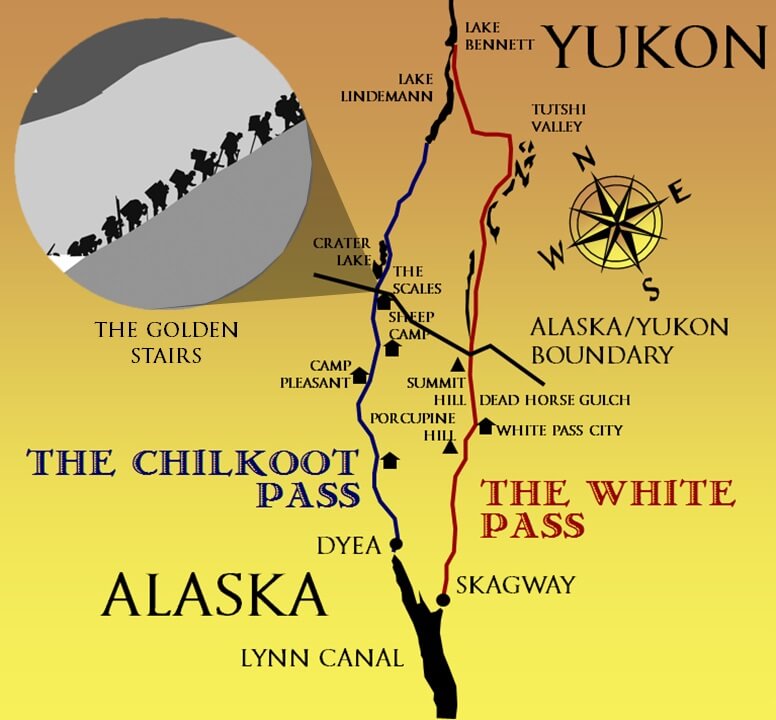

Throughout the summer of 1897, thousands of would-be prospectors traveled north up the Pacific Coast via steamboat. Many of the steamboats that carried them were bound for the Lynn Canal, an Alaskan inlet which penetrated the mainland about 540 km southeast of the Klondike. From Lynn Canal, Stampeders would hike either the Chilkoot Trail or the White Pass over the Coast Mountains to Lakes Lindemann and Bennett, respectively, from which they would travel up a series of lakes and rivers to the Klondike.

Other steamboats were bound for St. Michael, an old Russian port town situated on the west coast of Alaska where the Yukon River empties into the Bering Sea. From St. Michael, prospectors would travel 1,700 miles up the Yukon River to Dawson City and the Klondike beyond.

Some of the steamboats that went north that summer were reliable, seaworthy vessels that reached Lynn Canal and St. Michael unscathed. Tickets for these steamers were outrageously expensive, due to the high demand. These steamboats were packed well past their carrying capacity and as a result the voyage north was a veritable hell on earth.

Other steamboats that went north that summer were long-derelict ships that had been hastily patched up and commandeered by opportunists eager to take advantage of the situation. More often than not, these ships ran into trouble of one kind or another on their northern journey.

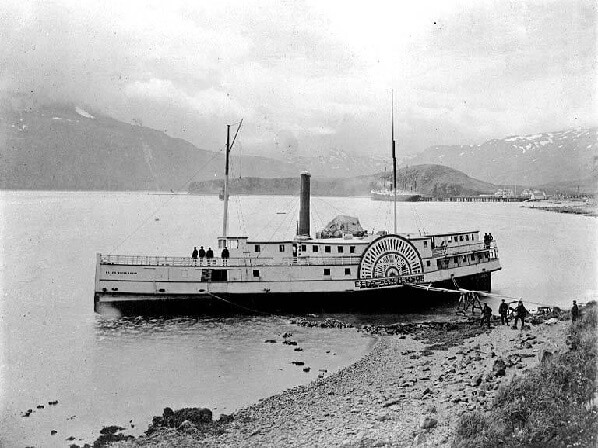

One of the sketchier ships to make the voyage to St. Michael in the summer of 1897 was the Eliza Anderson. This steamboat the oldest seagoing vessel on the coast. This ancient steamer had no propeller, old boilers, no electricity, no refrigeration, no compass, and shoddy coal-bunkers. After leaving port, the Eliza Anderson traveled without event to the port of Comox, on Vancouver Island. There, the ship took on coal. In an effort to save money, the crew decided to skimp on the fuel.

The crew was so inexperienced that they loaded the new fuel into the bunkers unequally. Because of this, the ship immediately veered to the side upon leaving the docks and rammed into another vessel, Glory of the Seas. Instead of returning to Comox, the captain of the Eliza Anderson decided to keep on going.

Next stop: the port of Unalaska, at the head of the Aleutian islands. The Eliza Anderson nearly reached her destination when she was beset by a violent storm. In the ensuing struggle, the ship ran out of coal. The crew desperately tore apart the ship’s interior, using the wooden boards and furniture for fuel. Soon, the ship was out of control. Passengers were writing farewell letters to their families. The situation was grim.

Suddenly, a grizzled, white-bearded stranger strode into the pilothouse from out of the storm. He took command of the ship and steered her to the safety of a bay of the proximate Kodiak Island. And as quickly as he had appeared, the stranger vanished into the spray.

As it turned out, the Eliza Anderson’s mysterious savior was a local Norwegian-born stowaway who had somehow managed to slip onto the ship without being seen. The Scandinavian, who had prior seafaring experience, was looking for a free ride to Unalaska.

Miraculously, the old Viking stowaway had steered the steamboat to a location a short distance from an abandoned cannery. There, the crew of the Eliza Anderson found a cache of much-needed coal. They loaded the fuel onto the ship and continued on their journey. The passengers were much relieved when the ruined steamboat slid into the old Russian port of St. Michael, Alaska.

Skagway

The Lynn Canal, one of the two major destinations of 1897 Stampeders (along with St. Michael, Alaska), branches into two small sections at its furthest point inland. One section is the Taiya (or Dyea) Inlet. The other is the Skagway Bay.

Skagway is an anglicized derivation of a Tlingit word which figuratively refers to the Lynn Canal’s rough seas, which are stirred up by strong northern winds. Literally, the Tlingit word translates as ‘beautiful woman’. According to Tlingit legend, Kanagu, or ‘Skagway’, was a beautiful woman who transformed herself into stone on the shores of the Skagway Bay, and was responsible for the area’s rough weather.

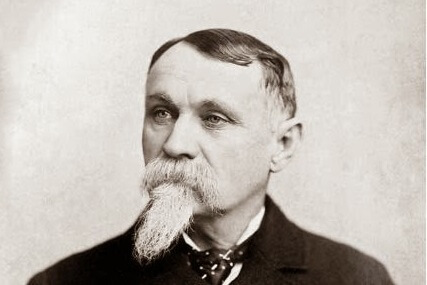

Before the Klondike Gold Rush, the only permanent resident of Skagway Bay was an old white man named Captain William Moore. Moore had lived a colourful life. The German-born adventurer spent his childhood aboard schooners in the North Sea. In his teens, he headed to New Orleans, where he ran a towboat service in the Mississippi. Moore enlisted in the American Army fought in the Mexican-American War of 1846/47. When the war was over, he took part in the famous California Gold Rush. For the next fifty years, he traveled from place to place, following various gold rushes. He prospected in Peru and Haida Gwaii. Then he followed gold to Fraser Canyon, where he set the example for Frank Laumeister, his Cariboo counterpart, by shipping camels up the Fraser River. After the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, he prospected in Cariboo Country and the Cassiar District.

Eventually, Moore’s prospecting ventures brought him to the Yukon. Long before the Klondike Gold Rush, the old prospector predicted that gold would be found somewhere in the Yukon Valley, and that a great gold rush would ensue. He also correctly predicted that many of the prospectors who flocked to the Yukon following such a strike would come by steamer to Skagway Bay on their way to the goldfields.

Skagway Bay lay at the foot of a mountain pass a short distance from the Chilkoot Pass long favoured by the local Tlingit. Moore, along with the Tagish giant Skookum Jim (one of the co-discoverers of Klondike gold), surveyed the pass at the behest of William Ogilvie, a Canadian government official who represented the Crown in the Yukon at the time. The pass was named White Pass after Sir Thomas White, the Canadian Minister of the Interior.

Moore was convinced that many prospectors would cross the Coast Mountains on their way to the Yukon goldfields by way of the White Pass. He envisioned a town rising up along the shores of Skagway Bay. According to his son, Bernard:

“My father would tell me and numerous other people in Juneau and elsewhere how he pictured to himself the future of this place. He never tired of predicting how roads would be built through here; of a little city built here; of steamers on the upper Yukon; and of large steamers, loaded with freight and passengers docking at the waterfront.”

Accordingly, White built a cabin at the foot of the White Pass in 1888. He hoped to establish himself as the founder of the boomtown he was certain would come into being, and to reap the rewards.

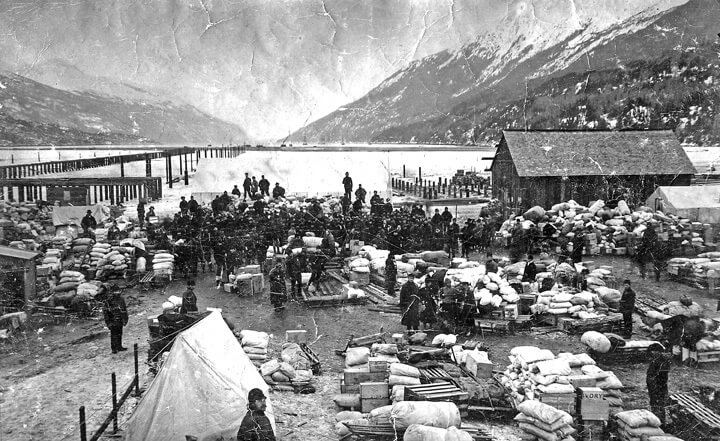

On July 26, 1897, Moore’s prophecy was realized. A steamer arrived at Skagway Bay and disgorged its passengers and cargo. Instead of showing the old prospector deference, which Moore believed he was entitled to as founder of the new town that would surely develop, the first wave of Stampeders largely ignored the old man and set about carving a campsite from the surrounding forest. Moore was enraged. However, he kept a cool head, cut his losses, and began to build a wharf out into the bay.

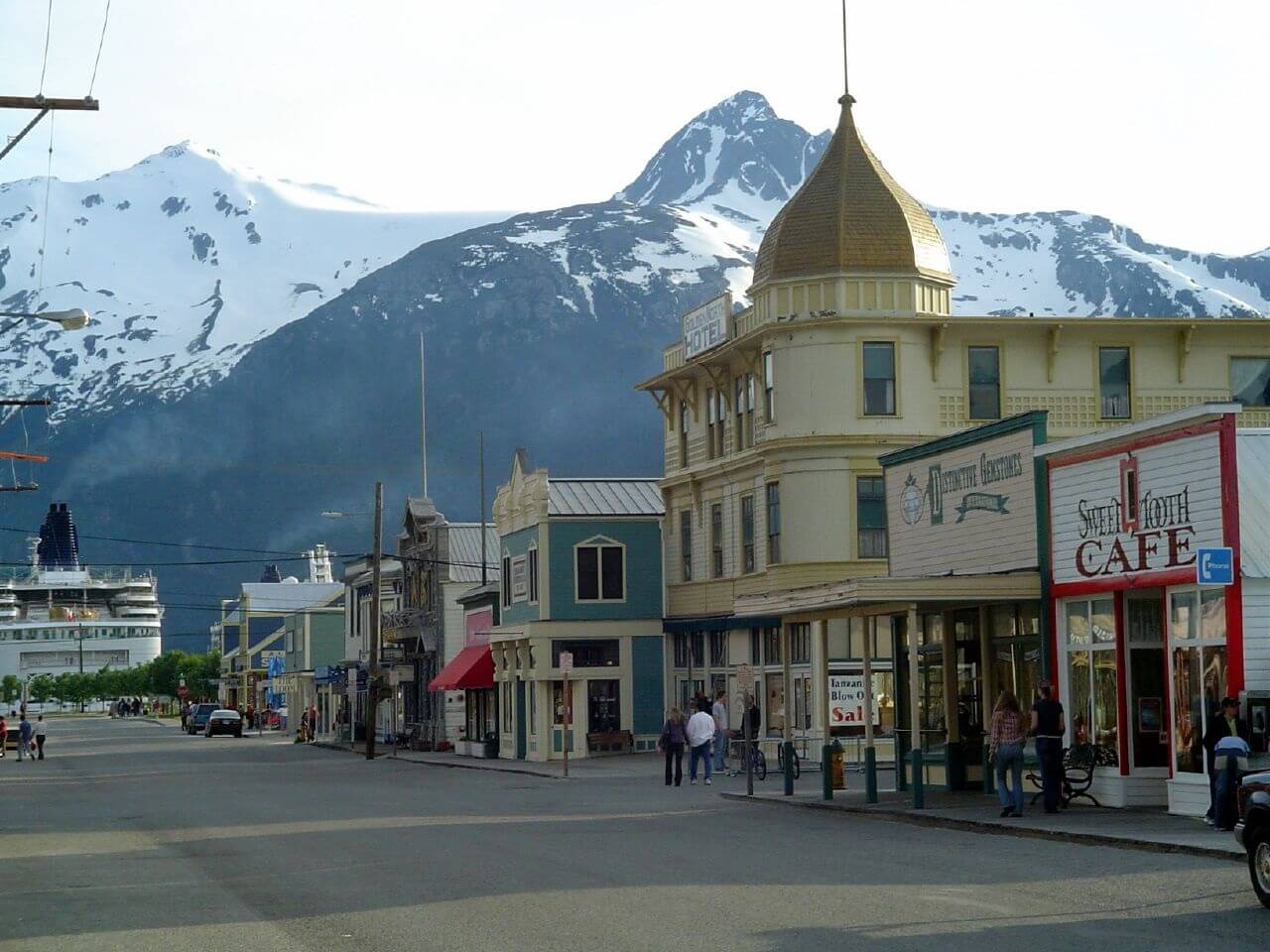

Throughout the summer, more and more Stampeders arrived at Skagway Bay. Trees were slashed and burned, crude log shacks were built, and soon a rough town began to take form. In early August, some of the town residents formed a local government. They dubbed the new town Skagway, after the Bay.

The Stampeder government laid out a plan for the new town. Streets were drawn up and surveyed. It just so happened that Moore’s old cabin lay right in the path of one of the streets. The Skagway government officials ordered Moore to vacate his cabin so they could demolish it.

The old prospector would have none of it, and refused to comply with the order. When a number of men came to Moore’s cabin, intent on evacuating him by force, Moore met them at the door with a crowbar in hand. After soundly trashing one of its members, the posse slunk off. Moore knew the Stampeders would have their way in the end, however, and reluctantly left his home.

In the following years, Moore made a fortune off the new arrivals who used his wharf to dock their ships. All the while, he hounded the Skagway government, seeking redress for the slights he had suffered at their hands. Eventually, his persistence paid off; Moore was given 25% of the assessed value of all the original Skagway lots.

During the summer of 1897, Skagway evolved (or devolved, depending on how you look at it) into a wild frontier town where the Law of Natural Selection reigned supreme. John Muir, the famous Scottish-American naturalist, described the town as “a nest of ants taken into a strange country and stirred up by a stick.” Pirates prowled the Bay, extorting huge fees from steamboat captains to haul cargo from the hold to the shore. Thieves and con-men skulked about the streets, relieving luckless Stampeders of everything they owned. Shootings were a nightly occurrence. In spite of the municipal government that had emerged in its early days, Skagway effectually became an anarchy.

In no time, saloons sprang up all over town. As a result, Skagway quickly developed a very colourful nightlife. Faro and blackjack games were constantly being played on rickety, rough-planed saloon tables. Next door to the saloons were the dance halls, where the pianos were played perpetually and girls in silk dresses danced with miners at a dollar per waltz.

According to Alexander Macdonald, a well-traveled Englishman who visited Skagway in the fall of 1897:

“I have stumbled upon a few tough corners of the globe during my wanderings beyond the outposts of civilization, but I think the most outrageously lawless quarter I ever struck was Skagway.… It seemed as if the scum of the earth had hastened here to fleece and rob, or … to murder.… There was no law whatsoever; might was right, the dead shot only was immune to danger.”

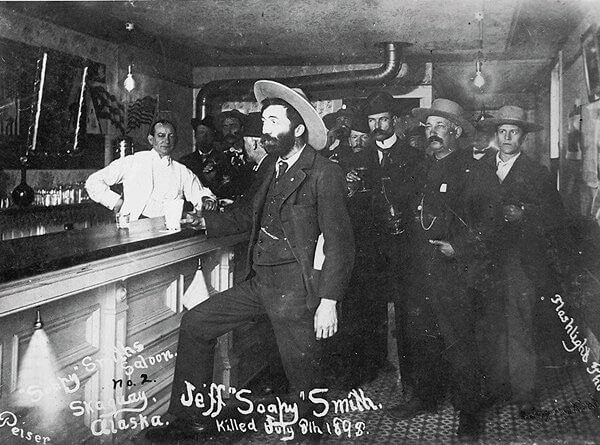

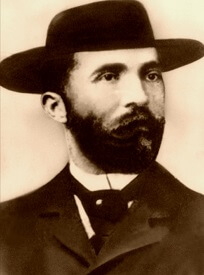

In January, 1898, a famous con-man named Jefferson Randolf “Soapy” Smith arrived in Skagway. Smith had acquired notoriety and fortune in Denver, Colorado, where he built a criminal empire. He earned his moniker “Soapy” from a lottery scheme in which he sold paper-wrapped soap bars to a crowd in Denver for $1 each, falsely claiming that in one of the soap bar packages was a $100 bill. He swindled his way to the top, hiring soldiers for his underground army until he was effectually the “Boss of Denver”. In the winter of 1897/98, Smith left Denver for Skagway, hoping to milk the boomtown of everything it was worth.

Soapy Smith quickly, artfully built up a gang in anarchic Skagway, rapidly expanding his range of influence until, in mid-winter, he practically owned the town. A crew of confidence men worked for Soapy Smith, preying upon hapless Cheechakos (newcomers to the north) newly arrived from the Outside. By hook or by crook, they extolled a heavy tax on nearly all newcomers to pass through Skagway on their way to the goldfields.

The White Pass

Stampeders who landed in Skagway continued on to the Klondike goldfields by way of the White Pass, the mountain pass over the Coast Mountains which connected Skagway with Lake Bennett.

In the summer and fall of 1897, the White Pass was almost perpetually choked with Stampeders on their way to the Klondike. According to Frank Thomas, an Indianan Stampeder who took the White Pass in the fall of 1897:

“I am a few days older than when I left … and a great deal wiser. I have been working like a slave since I came here trying to get over the trail and am not over yet, and furthermore do not think I will be in time to get down the Yukon this winter. Since I came in we have lost our mule and one horse on this accursed trail.… This is the most discouraging work I ever did.… There are thousands of people here … all mad and crazy just like us.… I am undoubtedly a crazy fool for being here in this God-forsaken country but I have the consolation of seeing thousands of other men in all stages of life, rich and poor, wise and foolish, here in the same plight as I.”

The first major obstacle on the White Pass was a sheer-sloped geological formation named Devil’s Hill. The early Stampeders carved narrow switchbacks through the hill’s scree. The path was so precarious, and the hillside so steep, that a poorly-loaded, off-balance horse could easily fall to its death.

The next obstacle Stampeders had to overcome was Porcupine Hill. This was a metaphorical minefield littered with ten-foot boulders which loaded pack horses had to pick their way over. One misstep would result in a broken foot and a dying horse.

The last of the major hurdles on the White Pass was Summit Hill, a thousand-foot hill composed of mud, boulders, and sharp scree. Summit Hill was pocked with muddy sinkholes which claimed the lives of many a horse. After that was the thousand-foot Turtle Mountain and the Tutshi Valley below. At the end of the White Pass lay Lake Bennett.

During the Stampede of 1897, the White Pass earned the nickname ‘Dead Horse Trail.’ Hundreds upon hundreds of animals were claimed by the trail. Some were pushed to their limits by their handlers. Many others succumbed to the trail’s hazards. By the fall of 1897, the White Pass was littered with half-frozen, half-rotten equine carcasses.

One of the men to witness the horrors of the White Pass was former NWMP officer James Morrow Walsh. Walsh was a man with an interesting past. He was one of the few original officers of the North West Mounted Police, and had been a member of the Force since its inception in 1873. In the mid-late 1870’s, he acted as the Commanding Officer at Fort Walsh, an early NWMP fort built near the site of the Cypress Hills Massacre. He earned his reputation in the late 1870’s, when he was tasked with treating with thousands of Sioux under the leadership of chief Sitting Bull, who had fled north into Canada following the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Walsh became fast friends with the outlaw chief and convinced him and his Sioux to abide by Canadian law while north of the border. However, he ultimately failed in his objective to convince Sitting Bull to return to America. Walsh’s superiors suspected his friendship with the Sioux chief was preventing him from fulfilling his duty, and so Walsh was stripped of his command and transferred to Fort Qu’Appelle in present-day Saskatchewan. In August 1897, he was appointed Commissioner of the Yukon, and was en-route to Dawson City, where he would take up his new position, when he first met with the carnage of the White Pass. Walsh described the macabre scene in a to Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior:

“Such a scene of havoc and destruction … can scarcely be imagined. Thousands of pack-horses lie dead along the way, sometimes in bunches under the cliffs, with pack-saddles and packs where they have fallen from the rock above, sometimes in tangled masses filling the mudholes and furnishing the only footing for our poor pack animals on the march – often, I regret to say, exhausted but still alive, a fact we are unaware of until after the miserable wretches turn beneath the hoofs of our cavalcade. The eyeless sockets of the pack animals everywhere account for the myriads of ravens along the road. The inhumanity which this trail has been witness to, the heartbreak and suffering which so many have undergone, cannot be imagined. They certainly cannot be described.”

Another interesting man to traverse the White Pass during the Stampede of 1897 was 21-year-old writer Jack London. London- who would go own to write his famous novels White Fang and The Call of the Wild, for which his Klondike experience would serve as a source- wrote:

“The horses died like mosquitoes in the first frost and from Skagway to Bennett they rotted in heaps. They died at the rocks, they were poisoned at the summit, and they starved at the lakes; they fell off the trail, what there was of it, and they went through it; in the river they drowned under their loads or were smashed to pieces against the boulders; they snapped their legs in the crevices and broke their backs falling backwards with their packs; in the sloughs they sank from fright or smothered in the slime; and they were disembowelled in the bogs where the corduroy logs turned end up in the mud; men shot them, worked them to death and when they were gone, went back to the beach and bought more. Some did not bother to shoot them, stripping the saddles off and the shoes and leaving them where they fell. Their hearts turned to stone – those which did not break – and they became beasts, the men on the Dead Horse Trail.”

A number of Stampeders who lost their mounts on the White Pass returned to Skagway, where they spent the winter. When winter came, the Dead Horse Trail became impassable, and the heavy stream of prospectors came to a trickle and then to a halt. Skagway soon swelled to a town of 5,000.

In the spring, when the Pass opened up, Stampeders found that the North West Mounted Police had established a customs house at its summit, on the Yukon-Alaska border. The Mounties were there to enforce a new regulation: all Stampeders to pass into Canada were required to be in possession of at least one year’s supply of food (about 1,150 pounds). In order to transport this much food, Stampeders would have to travel back and forth along the White Pass, hauling their supplies in manageable loads.

Duty at the customs house was a pitiable job. The mountain conditions were deplorable, and many of the 20-man crew stationed there fell ill. The Mountie in charge of the post- an Inspector named Strickland- suffered from a long bout of bronchitis. Eventually, Strickland’s superior, a Mountie named Sam Steele, in spite of the fact that he, too, was suffering from bronchitis, decided to personally relieve Strickland of the detestable duty.

Sam Steele was another man with an interesting Canadian past. Like James Walsh, he had been a Mountie since the NWMP’s inception in 1873. In fact, he and Walsh together had drilled the first Mountie recruits on horseback in the fall and winter of 1873/74. Along with rest of the original NWMP officers, Steele made the long 1874 trek to the western Canadian plains, where he helped to quell the illicit whisky trade and establish law and order in what would one day become southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. Years later, in 1885, Sam Steele commanded a squadron of North West Mounted Policemen and fought to suppress Louis Riel’s North-West Rebellion. On June 3, 1885, he led a 75-man mixed detachment consisting of both Mounties and Canadian militia to victory against 150 Cree warriors under the command of chief Big Bear. That battle, known as the Battle of Loon Lake, was the last major skirmish of the North-West Rebellion. In fact, the Battle of Loon Lake remains to this day the last battle fought on Canadian soil (knock on wood). In 1887, Steele led a detachment to a town called Galbraith’s Ferry in the British Columbian Rockies, situated a short distance from the Wild Horse Creek goldfields. There, he and his men resolved a dispute between the town’s white residents and local Kootenay Indians which might well have turned violent if not for their interference. Out of gratitude, the townspeople renamed their town Fort Steele. Today, Fort Steele remains a popular Canadian tourist attraction.

Sam Steele and Strickland before him made sure that no Stampeders without at least a years’ supply of food would cross into Canada. The Mounties were cognizant of the very real possibility of widespread starvation should there prove be more mouths than food in the Klondike. Earlier, in the fall of 1897, a handful of light-provisioned Stampeders managed to scale the Coast Mountains before freeze-up, build boats on the shore of Lake Bennett, and navigate the series of waterways to Dawson City. As winter approached, the threat of imminent starvation dawned on many of these first-on-the-scene Stampeders. During the late fall and early winter of 1897, hundreds of Stampeders newly arrived in Dawson returned the way they had come, or made a mad dash up the Yukon River for St. Michael, hoping to reach their destinations before the river froze or the trails were buried in snow. As a result of this panicked diaspora, there was no widespread starvation in the Klondike that winter. The Mounties were determined to keep it that way.

Dyea

Stampeders who came to the north by way of the Lynn Canal had two options: 1) they could unload their cargo on Skagway Bay and make their way over the White Pass; 2) they could disembark at the Dyea (or Taiya) Inlet, about 5 km to the northwest of Skagway, and scale the Chilkoot Pass.

Before the Stampede of 1897, the only white resident of the Dyea Inlet was a tough trader named John J. Healy. Like Walsh and Steele, Healy had an interesting Canadian past. Unlike the Mounties, however, he was not Canadian citizen. Healy was an Irishman who, as a young boy, emigrated with his family to New York in the midst of the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840’s. When he came of age, he enlisted in the United States Army. His service in the Force brought him to Utah, Idaho, and finally Montana. There, he settled down to the life of a trader at Fort Benton. In 1869, he, along with a small band of pioneering entrepreneurs, traveled north into Canadian territory and established the infamous Fort Hamilton (more commonly known as Fort Whoop Up) on the Belly River near present-day Lethbridge, Alberta. There, he sold trade goods, including whisky and repeating rifles, to the local Blackfoot. The whisky had a particularly devastating effect on the Indians, and in 1873, the Canadian government formed the North West Mounted Police and sent them west to suppress the trade. Instead of resisting the Mounties, Healy returned to Fort Benton, Montana, where he became the Sheriff of Chouteau County. During his term as sheriff, he jailed many interesting outlaws, including his famous Irish counterpart Kootenai Brown. In time, he left Montana for Alaska, correctly predicting that there would be a northern gold rush before the turn of the century. At the time of the Stampede, he was operating a trading post on the Dyea Inlet. Ever the entrepreneur, Healy made an honest fortune off the thousands of Stampeders who arrived on his doorstep beginning in the fall of 1897.

The Stampeders who unloaded at Dyea Inlet struggled to haul their supplies above the waterline before tide. Many unfortunates lost their outfits to the tide. Similar to Skagway, a town began to emerge on the shores. It was named Dyea after the Inlet.

Residents of Dyea took pride in the fact that their town saw considerably less crime than its neighbour Skagway. This was due, in part, to the fact that the Chilkoot Trail was open year round, as opposed to the adjacent White Pass, which was impassable in the winter. Because of this, Skagway swelled and stagnated, while Dyea remained a transient town through which Stampeders flowed perpetually. In the words of Dyea’s only newspaper, the Trail:

“We desire to call the attention of the reading public to the fact that no more orderly or peaceable city of 3,000 in population can be found in the United States.… The population of Dyea is composed of the better class and no one need feel alarmed. Property is exposed on all sides – hardly a case of theft occurring – and what few crimes that are committed are confined to a class few in number. There is less public exhibition of vice here than in the cities of the States.”

The Chilkoot Trail

After unloading their supplies at Dyea, Stampeders began the trek up the Chilkoot Trail, an ancient grease trail, or trading trail, long used by the local Tlingit Indians. The Chilkoot Trail was shorter than the White Trail, but more difficult. The route was arduous, and Stampeders had to contend with thieves, con-men from Skagway, the brutal sub-arctic elements, and the occasional avalanche. Many historians agree that it was, all things considered, the best path to the Klondike.

Five miles up the trail was Finnagan’s Point. The Point was a resting place before the grueling Dyea Canyon ahead, a narrow pathway littered with various natural obstacles. At the end of the Dyea Canyon was Camp Pleasant, a stopping point which offered Stampeders much-needed reprieve. The hike from Camp Pleasant to Sheep Camp- a tent town that emerged at the foot of the Coast Mountains- was uphill all the way. (Sheep Camp was so named because it was located at the site of an ancient Tlingit mountain sheep-hunting camp.)

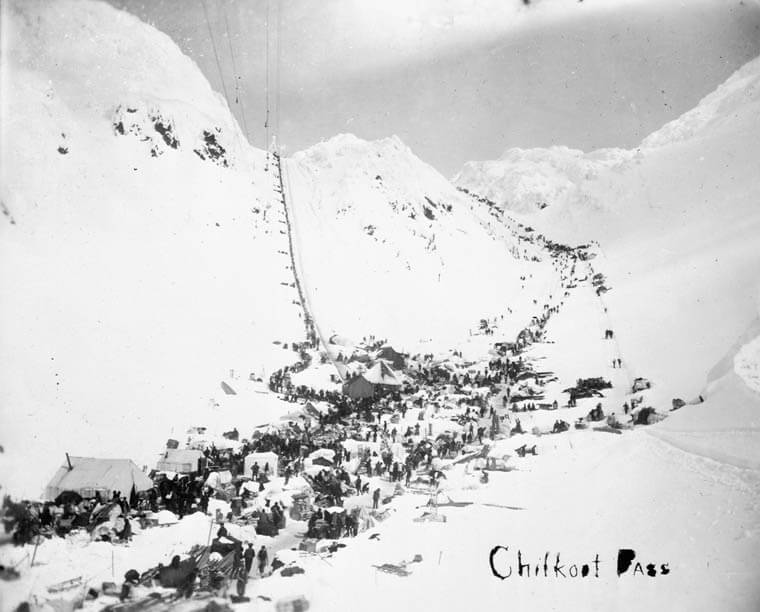

Past Sheep Camp, the trail became even steeper. Ultimately, it led to a flat ledge that came to be known as the Scales. Beyond the Scales were the famous Golden Stairs.

The Scales earned its name from the hundreds of Tlingit packers who camped at its base, offering their services to Stampeders. Here, the Tlingit men would use scales to meticulously measure the mass of the Stampeders’ gear. From thereon out, gear had to be hauled manually; the Golden Stairs were too steep for horses. The Tlingit were shrewd businessmen, and often charged prospector hopefuls $1 for every pound of gear they had to haul. They did not work on contract, and would almost always work for the highest bidder. Often, Tlingit packers would abandon their loads mid-trail if another Stampeder offered them a higher wage.

Just beyond he Scales were the Golden Stairs, the famous 15,000-step staircase hand-hewn from snow and ice which has since become an icon for the Klondike Gold Rush. Here, all throughout the winter of 1897/98, an endless line of Stampeders and Tlingit packers slowly snaked up the slope. The hike from base to summit usually took about six hours. At the top, men dumped their loads, marked their stash with a flag, and headed back down to the Scales. The trip down was much quicker, and infinitely more enjoyable; Stampeders simply slid down the slope on their rear ends, and reached the bottom in a matter of minutes. As a man could only conceivably haul a maximum of several pounds on his back in one trip, multiple trips were necessary. Without the help of a packer, a single Stampeder could expect to make the climb about 40 times in total.

Throughout 1897 and 1898, various entrepreneurs constructed tramways up that steepest section of the Pass, on which Stampeders could shuttle their supplies for a fee.

When a Stampeder had hauled everything he needed to the summit of the Chilkoot Pass, he proceeded to the North West Mounted Police customs house a short distance away. Similar to those stationed at the White Pass customs house, the Mounties on the Chilkoot stipulated that each Stampeder be in possession of at least one years’ supply of food. They also imposed a duty on the prospectors’ outfit.

After the Stampeders were permitted to pass into Canada, they made the journey down the other side of the Chilkoot Pass to Lake Lindemann. Lake Lindemann was connected to the adjacent Lake Bennett, which lay at the foot of the White Pass, by a narrow rapids. One Stampeder named John A. Matthews built a boat on Lake Lindemann and tried to paddle it through the canyon to Lake Bennett. He smashed the boat to kindling, lost his entire outfit, repeated the process, and destroyed his boat again. Stampeders learned from Matthews’ misfortune and, after building their boats on the shores of Lake Lindemann, portaged overland to Lake Bennett.

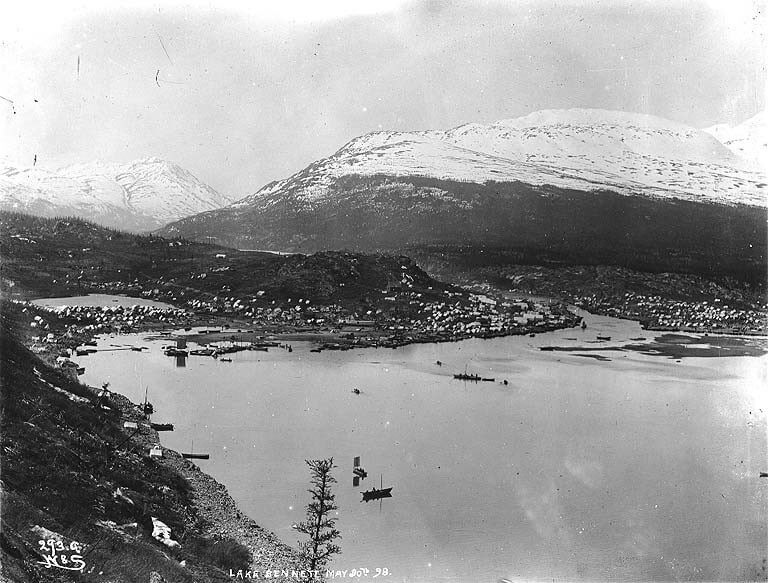

Most of the Stampeders of 1897 reached the shores of Lake Lindemann and Lake Bennett just in time for freeze-up. They had to spend the winter on the lake’s shores, waiting for the spring thaw, before making the dangerous journey down lakes and rapids to the goldfields of the Klondike.

Back to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 3: The Advent

Forward to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 5: Dawson Trails

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online book shop:

Leave a Reply