Back to The Klondike Gold Rush.

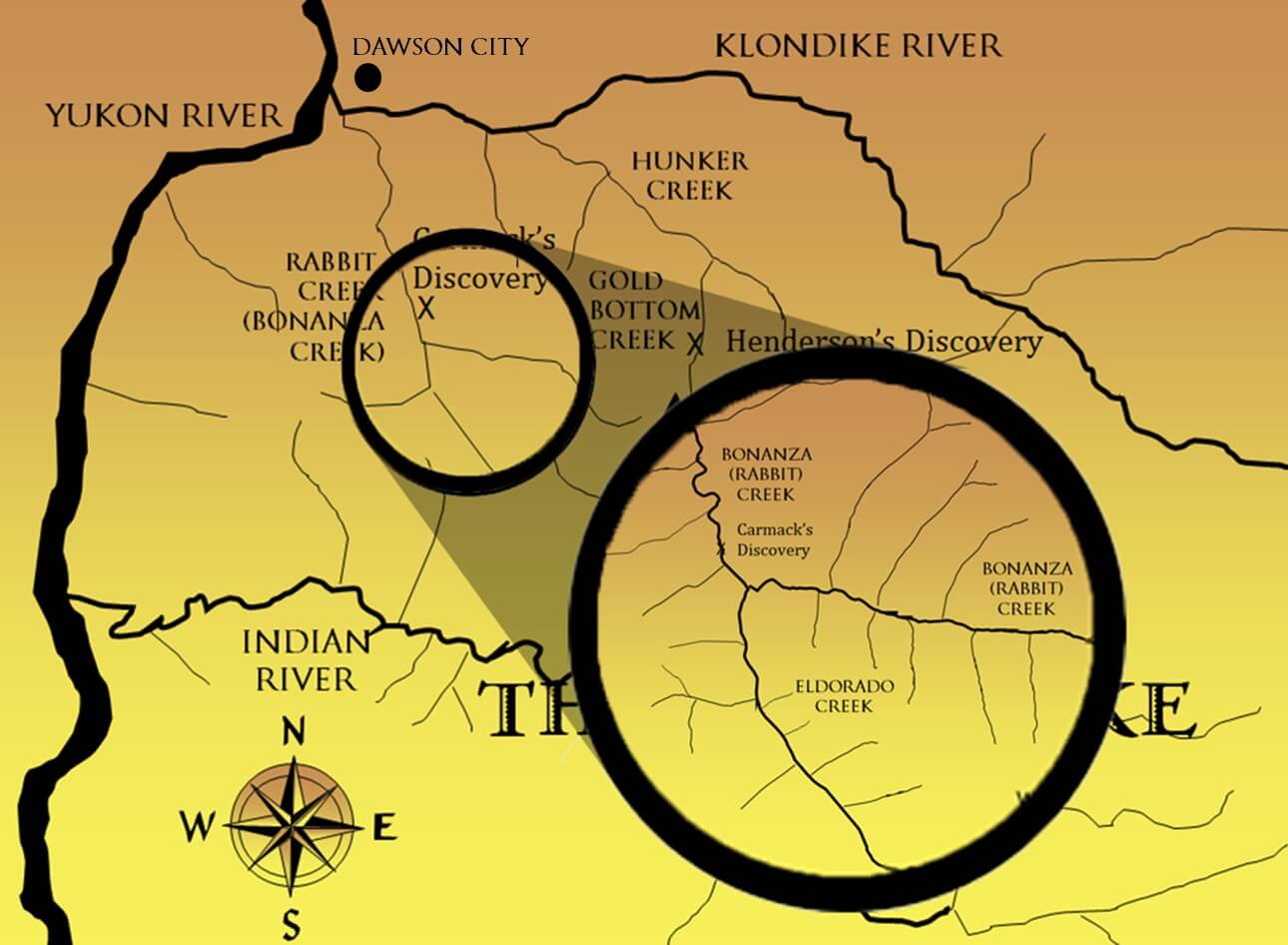

On August 16, 1896, George Carmack, Keish “Skookum” Jim Mason, and “Tagish” Charlie Dawson discovered a golden bonanza on Rabbit Creek, a tiny tributary of the Klondike River. Ever since that day, Rabbit Creek has borne the name Bonanza Creek. Without telling fellow prospector Robert Henderson of their find, as they had promised to do, the three men traveled down the creek to the Klondike River, down the Klondike to the Yukon River, and down the Yukon to the ramshackle frontier town of Fortymile to stake a claim, spreading the word of their find as they went. In no time, prospectors from all over the Yukon flocked to Bonanza Creek, scrambling to stake claims of their own. It was the beginning of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Early Days on Bonanza Creek

Some of the first prospectors to strike it rich on Bonanza were brothers Clarence and Fred Berry, former fruit farmers from Fresno, California. Clarence was a Sourdough (‘Sourdough’ is a Yukon-Alaska term which refers to someone who has spent at least one winter in the north) who spent the winter of 1894/95 prospecting on Fortymile Creek. When spring came, he traveled to California, married his childhood sweetheart Ethel Bush, and returned to the Yukon with his bride in 1896. Ethel was the first white woman to scale the Chilkoot Pass and travel down the Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon goldfields. After some more unsuccessful prospecting, Clarence took a job at a saloon in Fortymile. He was tending bar one day in August when George Carmack sauntered into the saloon, fresh from Bonanza Creek with a shotgun shell filled with gold nuggets. Clarence received an outfit on credit from his employer, Bill McPhee, and immediately set out with his brother to stake a claim on Bonanza Creek. That fall, the Berry brothers partnered up with a young Austrian immigrant named Antone Stander and sunk a shaft to bedrock. When spring came and they washed their dump pile in a sluice, the three men were rich.

Most prospectors were not as quick to reach bedrock as the Berry brothers. Many laboured throughout the winter, lighting fires by night and digging through melted permafrost by day. When shafts became deep enough, ladders where erected and windlasses were built. One prospector would dig in the shaft bottom with pick and shovel, filling a bucket with dirt. His partner would man the windlass, hauling up the bucket when it was filled and transferring the dirt to the dump pile before lowering the bucket back down again. The further the prospectors dug, the more they realized that Bonanza was no ordinary creek. Prospectors would haul up buckets of gravel glistening with gold nuggets. Pans of particular paydirt could yield up to eight hundred dollars worth of gold.

As word spread of the wealth to be had, prospectors vied fiercely for claims on Bonanza Creek. Men bickered and fought with one another over mining territory. Most major disputes were, in the end, settled by William Ogilvie, a Canadian government surveyor who had surveyed the Alaska-Yukon Boundary back in 1887/88.

The Bounty of Eldorado Creek

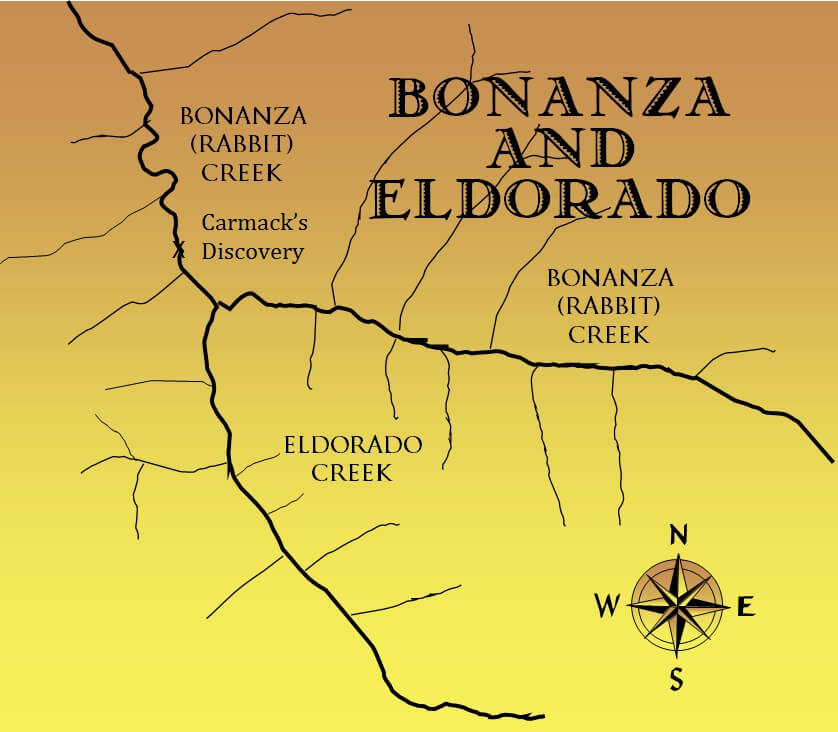

By late August, all of Bonanza Creek had been staked. In time, the creek’s south fork- a small stream known at the time as ‘Bonanza’s pup’- turned out to be particularly bountiful.

In late August, a party of five prospectors staked a claim on Bonanza’s pup. The party included: Antone Stander, the man who had earlier partnered with Clarence Berry; Jay Whipple, an old prospector from the nearby diggings on Sixtymile River; Frank Keller, a former railway man from California; J.J. Clements, a New Yorker; and Frank Phiscator, a farmer from Michigan. When the five men came to the creek, one of them dipped his pan at random into the stream bed and washed it out. At the bottom of the pan, mixed with heavy black sand, lay six dollars worth of coarse gold dust. The find was incredible. To put this in perspective, earlier that year Robert Henderson- a veteran prospector who made a habit of only settling down to dig after finding glowing prospects- decided to excavate a location on nearby Gold Bottom Creek after finding eight cents in his pan. Stander, Whipple, Keller, Clements, and Phiscator had unwittingly stumbled upon the richest gold-bearing creek in the world.

The five men pounded in their stakes immediately and got to work. Soon, they were joined by a party of four led by an Illinoisan named Louis Emkins. In defiance of the unwritten prospectors’ code which had characterized Yukon’s earlier gold rushes, Stander and his companions initially tried to discourage the newcomers from more closely inspecting the creek bed, saying they had found nothing but dirt. Emkins was unconvinced. He and his partner George Demars staked their own claims on the creek. The other two prospectors took Stander and his companions’ advice at face value returned the way they had come.

The third party to come to Bonanza’s pup included three Norwegians and an ex-reporter from Chicago named William Johns. There, the newcomers met with Emkins, Demars, and Frank Keller, all of whom were mysteriously vague about the creek’s prospects. Warily, the prospectors crept upstream, where they found Stander, Whipple, Clements, and Phiscator crowded around a pan. According to Johns, they looked “like a cat caught in a cream pitcher.” The four newcomers knew immediately that the creek was rich, and set about staking their own claims. One of the Norwegians jokingly dubbed the creek Eldorado. For reasons the newcomers would soon learn, the name stuck.

Soon, more prospectors ventured over to Eldorado from Bonanza Creek. Encouraged by the eleven pioneers who had settled down on the creek to dig, they decided to stake their own claims. In no time, every inch of Eldorado Creek was owned by one prospector or another.

Although the prospects on Eldorado Creek were better than good, nobody could tell how rich the area really was until a shaft was sunk to bedrock and the gravel washed in a sluice- a process which would take until spring. Some of the early prospectors on Eldorado sold their claims for a tiny fraction of their true value, leaving fortunes untouched in the permafrost. Jay Whipple sold his claim to a man named Skiff Mitchell for next to nothing. George Demars sold his stretch of land for eight hundred dollars. And William Johns sold half his claim for five hundred dollars, and the other half three months later for $2,500. In three years’ time, each of these claims would be worth over a million.

One of the most successful prospectors to stake a claim on Eldorado Creek was a massive, illiterate Nova Scotian labourer known as “Big Alex” McDonald. McDonald, who arrived in the Klondike nearly penniless, purchased an especially profitable stretch of land on the creek on credit. Instead of working the claim himself, he leased it to other men who mined for him. When the men had worked claim and reaped the rewards, Big Alex kept half the profit, and let the miners keep the rest. He used the profit to purchase more Klondike claims on which he repeated the process. Within a year, the Maritime giant rose from obscurity to fame and fortune, and earned himself the moniker “The King of the Klondike.”

The Dawn of Dawson City

The first trader to take advantage of the Klondike Gold Rush was Joseph Ladue, the man who had originally outfitted Henderson and urged him to prospect the watershed of the Indian River (a tributary of the Yukon River near the Klondike). In the fall of 1896, Ladue built a saloon and sawmill at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers, the site of an ancient seasonal Han fishing camp. Newcomers to the Klondike gravitated to the log buildings, and in no time a sizable tent town revolved around it. This tent town was the seed that would grow into the thriving boom town of Dawson City, the largest city the Canadian north has ever known.

In those first few seasons of the Klondike Gold Rush, goods were scarce in the tent town that would become Dawson City. Prospectors would pay hundreds of dollars for bent and burnt nails with which they would construct their sluice boxes. Butchers sold halves of beef for thousands of dollars. Food became so scarce that dog meat became a staple. Gold seemed to be the only commodity in good supply.

Throughout the fall of 1896 and the winter if ’96/’97, the Outside- a term northerners used to refer to the rest of the world- was largely unaware of the Klondike gold. Throughout the winter, a thin trickle of prospectors arrived by steamboat on the Yukon’s west coast, bound for Circle City, Alaska. These newcomers scaled the Chilkoot Pass, hiked up the Chilkoot Trail to Lake Bennett (a lake which led to the Yukon River), built boats on the lake’s shore, and waited for the spring thaw. When spring came, and the waters became navigable, the prospectors traveled down the Yukon River to their destination and stumbled upon the burgeoning town of Dawson. Upon stopping in the town’s saloons, hearing the stories, and catching glimpses of the gold nuggets with which Sourdoughs paid for their drinks, many abandoned their Circle City plans and set up camp in Dawson.

When spring came, the Klondike prospectors who had worked throughout the winter washed the dirt from their dump piles in sluice boxes and collected the gold which sank to the bottom. Many of them ended up extraordinarily wealthy. While many had earned their wealth working claims on the creeks of the Klondike, however, others made fortunes by catering to the prospectors who returned to Dawson from the diggings. Ten cent cigars sold for $1.50. Log cabins sold for $200/square foot. The price of bacon and tea was inflated to eight times its original value. Fresh eggs were priceless.

By summer, Dawson had swelled to a town of 3,500. According to Charles Constantine, the head of the NWMP detachment in the Yukon at the time, many of the newcomers “appeared to be the sweepings of the slums and the result of a general jail delivery.” Soon, rough-hewn log buildings were being built all over town, replacing the tents that had dominated the area all winter. This new Dawson was a new breed of northern mining town, one which’s character differed starkly from that of the other Yukon-Alaska boom towns which preceded it. In Dawson, the Golden Rule and the old, unwritten Prospectors’ Code to which the Sourdoughs of Fortymile and Circle City had adhered was eclipsed by greed. No longer could prospectors leave their cabin doors open to passing travelers and expect their goods and gold to remain untouched.

In early June, two steamboats arrived in Dawson loaded with food, alcohol, and other supplies. One was the Alaska Commercial Company’s steamboat, Alice. The other was a vessel privately owned by John J. Healy, an American merchant with an interesting Canadian past who had a trading post on the Dyea Inlet. After Healy and the ACC employees aboard sold their wares to the boom town merchants, the two steamboats took on passengers who wished to return to the Outside. Some of these passengers were prospectors who had struck it rich on the Klondike, and were eager to blow their wealth in the bars of Seattle and San Francisco. These ragged prospectors would become the first heralds to bring word of the tremendous wealth to be made on the Klondike to the Outside world. And thus began the heyday of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Henderson’s Misfortune

“Hey, wait a minute,” some of you might ask, “whatever happened to Robert Henderson, the first guy to find gold in the Klondike?” If you haven’t read our article on the Klondike gold discoveries and have no idea what I’m talking about, have no fear; I’ll give you a brief summary of that story in the paragraph below:

Just days before their famous August 16 discovery which catalyzed the Klondike Gold Rush, George Carmack, Skookum Jim, and Tagish Charlie visited a prospector named Robert Henderson at his mining camp. Henderson- who, at the time, was mining on a tributary of the Klondike River he had dubbed Gold Bottom Creek- had came upon the three men earlier that summer at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. There, he told Carmack, a white, of the good prospects he had found on Gold Bottom Creek. At the same time, he insulted Carmack’s companions, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie (both of them Tagish Indians), by informing them that they were not welcome to stake claims on the creek. With that, the two parties went their separate ways; Carmack’s group up Rabbit (Bonanza) Creek, and Henderson’s up the Klondike (from which he would travel up what would become Hunker Creek to Gold Bottom). Some time later, Carmack and his companions found themselves in the vicinity of Gold Bottom Creek. They visited Henderson at his work camp, exchanged some words, then returned in the direction they had come with a promise to send word to Henderson if they found gold. On August 16, they made their discovery and, without sending word to Henderson as they had promised, traveled to Fortymile with the news.

While prospectors from all over the Yukon funneled onto Bonanza Creek, Henderson toiled away on Gold Bottom, oblivious. One day in early September, two prospectors stumbled into his work camp. They had traveled the length of Bonanza Creek, and were in search of fresh prospects. Henderson spoke with them and quickly learned of the three-week-old gold rush on Bonanza Creek, and of Carmack’s betrayal. Swallowing his dismay, Henderson realized he would need to stake a claim on Gold Bottom quickly before overflow from Bonanza Creek reached the area. He set off immediately down the creek, bound for Fortymile.

Gold Bottom was a tributary of a longer creek which flowed into the Klondike. After travelling down that nameless creek for some time, Henderson came upon two prospectors: Charles Johnson and the more senior Andrew Hunker. The two men informed Henderson that they had found quality colour on the creek. Because of their find, and Hunker’s seniority, the creek would be known thereafter as Hunker Creek. The find was richer than Henderson’s find on Gold Bottom, and Henderson determined it would be worth his while to forfeit his discovery claim in order to stake a claim on this new creek. With that in mind, he continued on to Fortymile, where he staked a claim on Hunker Creek.

Henderson never had the opportunity to work his claim. Earlier that year, while prospecting in the bush, he had badly injured his leg. The injury prevented him from working his claim that winter. When spring came, he opted to do some more prospecting on the Klondike tributaries before returning home to his family in Colorado. At Fortymile, he boarded a steamboat bound for St. Michael, Alaska, from where he hoped to board another steamer which would take him down the Alaskan Panhandle and the British Columbian coast to Seattle. Unfortunately, the ice which formed on the Yukon River mid-journey proved to be too much for the steamer, and Henderson was forced to spend the winter in Circle City, Alaska. There, he fell ill, and was forced to sell his claim on Hunker Creek in order to pay for his medical bills. In years to come, that claim would prove to be one of the richest claims on the creek.

In the spring, Henderson finally made it to St. Michael. Next, he traveled by steamer to Seattle. At last, he arrived back home in Colorado with nothing to show for his discovery of the gold that would help launch the Klondike Gold Rush. In the end, the co-discoverer of the Klondike Gold Rush returned home penniless.

Back to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 2: The Discoveries

Forward to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 4: The Stampede

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online book store:

Susan Slick

My great grandfather from New York wrote a diary of his 1897-98 trip up Chilkoot Pass and the Dyea Trail and trek to Dawson where he worked for Healy unloading the Alice and received pies from Mrs Healy.