Back to The Klondike Gold Rush.

By 1896, nearly a decade had passed since the gold rush of Fortymile River (one of the many tributaries of the Yukon River). In the space of that decade, prospectors from all walks of life had flocked to the Yukon to try their luck on the Fortymile and the creeks surrounding it. In 1891, gold was discovered on the Sixtymile River (which flowed into the Yukon River sixty miles upriver of Fort Reliance), and many prospectors left the Fortymile for the new diggings. The following year, gold was discovered on Birch Creek, Alaska, and the process was repeated. The miners who congregated on Birch Creek founded a boom town which they named Circle City, after its proximity to the Arctic Circle. A handful of miners struck it rich and returned to civilization with small fortunes, or blew their wealth in the saloons of Fortymile and Circle City. Many more toiled to no avail and left the Yukon broke and embittered. A ragged scattering of Sourdoughs, a term used to describe seasoned prospectors who had weathered at least one northern winter, remained behind. And every once in a while, small parties of tenderfoot Cheechakos– newcomers to the north trickled over the Chilkoot Pass, hungry for fortune, adventure, and respite from Victorian society. By 1896, there were 1,600 men scouring the Yukon and Alaska for gold. Few might have guessed that, in two years’ time, the area would be home to 30,000 prospectors. Few might have guessed that the Klondike River, an obscure tributary of the Yukon, would be the site of the Klondike Gold Rush, the biggest gold rush in Canadian history.

Henderson’s Discovery

One of the Sourdoughs who lived in the Yukon in 1896 was a Nova Scotian named Robert Henderson. He was one of the co-discoverers of the gold that launched the Klondike Gold Rush.

Henderson was a prospector to the core, and had spent his entire adult life searching for gold. He left Nova Scotia at a young age to pan the goldfields of Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand. After years of labouring fruitlessly under the southern sun, he left for Pike’s Peak Country of what is now Colorado, USA. Over the years, he panned and picked his way north up the Rocky Mountains until he found himself in the Yukon. Instead of trying his luck near Fortymile, Sixymile, or Circle City, he panned himself penniless on the Pelly River, a headstream of the Yukon River. When he reached rock bottom, he poled down the Pelly to the Yukon River, then floated down the Yukon to Ogilvie, a hamlet at the mouth of the Sixtymile River. There, he met with Joseph Ladue, co-owner of the community’s trading post.

Back in the 1880’s, Joseph Ladue had partnered with Arthur Harper, Jack McQuesten, and Alfred Mayo, the three patriarchs of the Yukon. Together, the four men traded tools and provisions to Yukon prospectors. Over the years, they had outfitted nearly every miner in the area. In accordance with the strange prospector’s etiquette to which nearly all northerners adhered, the four traders frequently supplied men on credit alone. Henderson hoped to take advantage of this Sourdough’s code of honour and secure himself an outfit.

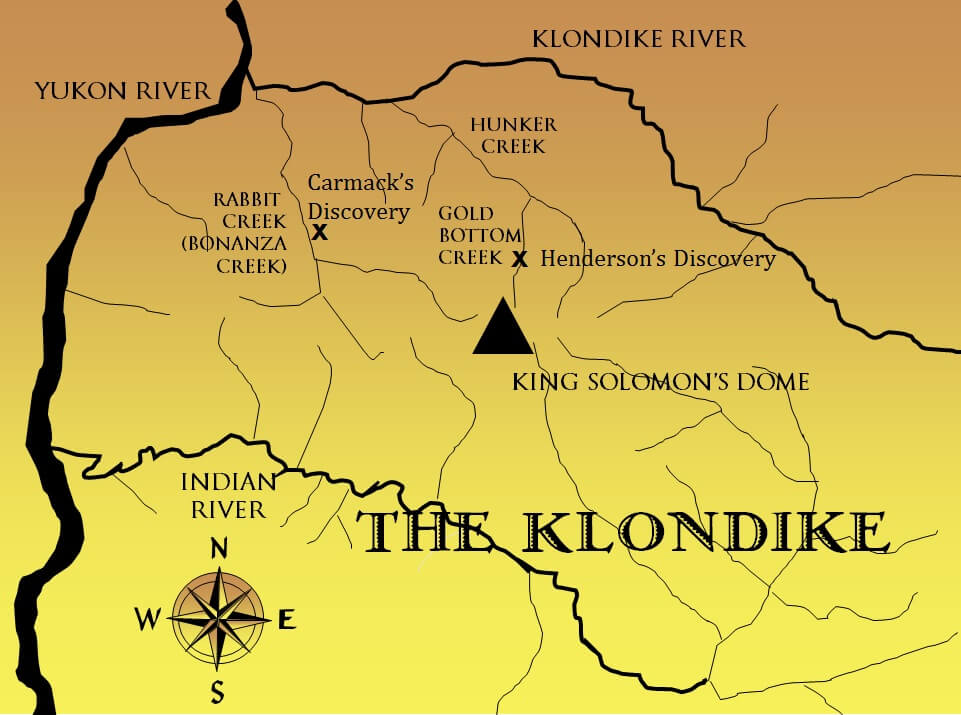

Ladue was better than his reputation. He lent Henderson everything he would need for another prospecting venture, and even advised him where to pan. The Klondike River- or Tr-ondek, as the local Han Indians called it- would never yield quality gold, Ladue maintained. However, the trader believed wholeheartedly that the silt at the bottom of the Indian River concealed a wealth of gold just waiting to be discovered.

Henderson set off immediately, taking Ladue’s advice. He panned the Indian River and its tributaries doggedly. He found placer gold here and there, but never enough to warrant a more thorough investigation. While he moved from stream to stream, Henderson noticed something interesting. All the Indian River’s northern tributaries seemed to flow from a single source: a round peak which towered over the surrounding hills. Perhaps spurred by a prospector’s curiosity, Henderson decided to explore the peak. After a grueling 4000-foot climb, Henderson crested the mountain and met with a spectacular sight.

The round mountain- which would one day become known as King Solomon’s Dome- was a focal point from which creeks flowed in all directions, like tentacles from the body of an octopus. The creeks on the mountain’s southern slopes flowed into the Indian River. The creeks on the east side flowed into the Yukon. And the creeks on the northern slopes flowed into the Klondike River.

Upon his ascent, Henderson happened to be closest to the head of a small tributary of what would become known as Hunker Creek. Out of curiosity, he shambled down the hillside and followed the creek until he found a suitable place to pan. The prospector dipped his pan into the creek bed and washed away the gravel. At the bottom of the pan he found heavy black sand and eight cents of coarse gold. The find was promising, and Henderson made the trek back to the Indian River to share the news with fellow prospectors, as was Sourdough custom. Little did he know that his discovery would set in motion a chain of events which would culminate in the Klondike Gold Rush.

Henderson returned to the creek on the northern slope of the Dome- which he named Gold Bottom Creek- with three other men. The miners began to dig a shaft and extracted $750 before running low on supplies. On their way back to Ladue’s trading post, Henderson and his new partners shared the news of their find with every prospector they came across. They outfitted themselves at Ogilvie and promptly poled back up the Klondike to return to their diggings. Instead of travelling up the Indian River, which was dangerously shallow when, the prospectors decided to pole up the Klondike, and then up Hunker Creek to Gold Bottom.

Carmack’s Gold Discovery

At the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers, at the site of present-day Dawson City (the future epicentre of the Klondike Gold Rush), Robert Henderson and his companions came upon a party of five. The party included ‘Skookum’ Jim Mason, ‘Tagish’ Charlie, Kate Carmack, Kate’s daughter Graphie Gracey, and Kate’s husband George Carmack. These five, like Henderson, would go down in posterity as the co-founders of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Keish ‘Skookum’ Jim Mason was the largest of the five. On the surface, he appeared to be a massive Tagish Indian. Years later, George Carmack described him as, “straight as a gun barrel, powerfully built with strong sloping shoulders, tapering… downwards to the waist, like a keystone. He was known as the best hunter and trapper on the river, in fact he was a super-specimen of the northern Indian.” On the inside, however, Skookum Jim was as ambitious as any white man. In general, the Tagish Indians of Lake Tagish and Lake Bennett contented themselves with hunting and fishing and cared little for wealth and power, unlike their competitive Tlingit neighbours on the other side of the Coast Mountains. Skookum Jim was an anomaly. In the mid-1880’s, he hauled prospectors’ supplies over the Chilkoot Pass for money alongside Tlingit packers. After packing an enormous 156-pound load of bacon over the Pass, he earned the nickname ‘Skookum’, meaning ‘burly’ in Chinook Jargon (a trade language of the Pacific Northwest). Skookum Jim was also a prospector, and dreamed of striking it rich.

‘Tagish’ Charlie was Skookum Jim’s nephew, but he was not a giant like his uncle. Lean and limber, Tagish Charlie was, according to George Carmack in a later reminiscence, “alert as a weasel”.

Kate Carmack was Skookum Jim’s sister. Her mother was a member of the Tagish Wolf moiety and her father, Kaachgaawaa, was the chief of the Tlingit Crow moiety. According to local Indian tradition, she was the heir to her father’s title. Her daughter, young Graphie Gracey, was a mixed blood born to George Carmack.

George Carmack was the only white man of the group. He was Kate Carmack’s husband, Graphie Gracey’s father, Skookum Jim’s brother-in-law, and Tagish Charlie’s uncle. Carmack was a trader, fisherman, and trapper who had adopted the lifestyle of an Indian. Unlike Skookum Jim, his massive brother-in-law, he cared little for gold, and contented himself with living off the land and selling fish, lumber, and furs for white amenities. In contrast with many Yukon prospectors who took Indian wives and brought them into their cabins, Carmack took the Tagish-Tlingit Kate for his wife and moved into her caribou-skin lodge. For this, he was largely despised by fellow Sourdoughs. This effect was compounded by the fact that George Carmack had the nasty habit of stretching the truth. According to one Mountie stationed at Fortymile, Cormack was a man “who would never allow himself to be beaten and always tried to present his fortunes in the best possible light.” In the Yukon Valley, many whites referred to him as ‘Lying George’.

Earlier that year, in May, the party of five was camped on the banks of the Yukon River near the charred ruins of Fort Selkirk, a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post that had been razed by Tlingit warriors in 1852. According to legend, one evening, George Carmack had a strange, prophetic vision. While staring into the sunset, he had a feeling that something remarkable was about to happen. He took out a coin and decided to flip it. If it landed on heads, he would go up the Yukon River. If it was tails, however, he would head down the river. The coin landed on tails. Later that night, while he was sleeping, Carmack dreamed that he was approached by two massive salmon. Their scales were made of gold, and their eyes were twenty-dollar gold pieces. Upon meditating upon his dream, Carmack- instead of interpreting the dream as a sign to go prospecting, as many white men would certainly do had they been in his position- decided that the proper course of action was to head south and go fishing.

And so George Carmack, his wife Kate and daughter Gracie, Skookum Jim, and Tagish Charlie found themselves fishing at the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers when they were approached by Robert Henderson and his partners.

Henderson, a strict adherent to the prospectors’ code, informed Carmack of his find on what was now Gold Bottom Creek. However, like many Sourdoughs, he harboured a prejudice against Indians, and didn’t want to see any of them staking claims on the site. He told Carmack as much, and made sure that his Tagish family were aware that they were not welcome at Gold Bottom Creek. With that, Henderson and his party headed up the Klondike River.

Carmack, who did not lust after gold like his white counterparts, would not abandon his family to chase after the yellow metal. After some deliberation, the party of five decided to head up Rabbit Creek (a creek which flows from King Solomon’s Dome into the Klondike River just before its confluence with the Yukon) to scout out quality timber, which they might fell, dress, and float downstream to Fortymile. They cached their boat at the creek’s mouth and headed up its banks on foot. In time, they came to King Solomon’s Dome. On a whim, they decided to hike over the slope to visit Henderson and his crew, who were working an open cut.

Historians are divided about what exactly was said between the two parties on that fateful meeting. However, most agree that at least three things happened that day on Gold Bottom Creek: 1) it was decided that Carmack and his family would head back to Rabbit Creek; 2) Carmack promised Henderson that he would send back word if he or any of his Tagish family found anything worthwhile on Rabbit Creek; 3) Henderson refused to sell any of his tobacco to Skookum Jim or Tagish Charlie. When they had concluded their visit, Carmack and his family left Gold Bottom Creek the way they had come and headed back over the ridge to Rabbit Creek.

That evening, on August 16, 1896, George Carmack and his family made camp about half a mile downstream of the headwaters of Rabbit Creek. While Carmack dozed under a birch tree, Skookum Jim headed into the brush with his rifle, hoping to bag a moose for supper. The big Indian succeeded, and went to the river to wash out a frying pan in which he would cook some of the meat. As he was cleaning the pan, he noticed that a protruding rim of bedrock was shimmering dully in the light of the setting sun. He examined the rock and pulled out a piece of solid gold as large as his thumb.

Elated, Skookum Jim informed his family of the find. The big Indian, Tagish Charlie, and George Carmack whooped for joy and danced around the pan. Said George Carmack in a later reminiscence, “I felt as if I had just dealt myself a royal flush in the game of life, and the whole world was a jackpot.” After they were finished celebrating, the three men panned Rabbit Creek- which would then be known as Bonanza Creek- and accumulated enough gold dust to fill a Winchester shotgun shell. After staking claims on the creek the following morning by writing on the wood of a nearby spruce, the party headed downstream towards the Yukon River, and to Fortymile beyond, spreading the word of their find to every prospector they came across. Some of those prospectors to first learn of the bonanza- including Dan McGillivery, Dave Edwards, Harry Waugh, Dave McKay, and Alphonse Lapierre- would become millionaires. In their haste, or perhaps out of spite, George Carmack and his family neglected to send word of their strike back to Henderson as they had promised.

Word of the find on Bonanza Creek spread like wildfire throughout the Yukon Valley. Soon, the goldfields of Fortymile, Sixtymile, and Circle City were emptied as every prospector in the north flocked to the Klondike for a piece of the pie. It was the beginning of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Back to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 1: Background

Forward to The Klondike Gold Rush- Part 3: The Advent

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Leave a Reply