Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XXIV – Indian Farm Started.

Chapter XXV

Governor General Visits Northwest

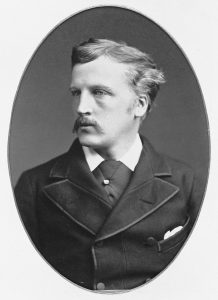

THE COMMISSIONER of the Police was notified from Ottawa during the summer of 1881, by the Comptroller of the force, Mr. F. White, that it was the intention of the Marquis of Lorne, the Governor General of Canada, to visit the North-west Territories during that summer, and to have escorts of police in readiness to accompany his party in their journey through the country. In July an escort left Fort Walsh in charge of Sergeant-Major Lake for Qu’Appelle, it being arranged that Superintendent Herchmer should meet them at that place. I might mention that, as heretofore the ranks in the force had been constables, acting constables and sub-constables, they had this year been changed to sergeants, corporals and constables, and the commissioned ranks, being previously inspectors and sub-inspectors, were now superintendents and inspectors. The uniform had also been materially changed. The party from Fort Walsh consisted of sixteen constables, three corporals and three staff sergeants, with thirty one horses and three wagons. The party under Superintendent W. Herchmer’s command was to meet the Governor General at Fort Ellice, which was situated about 400 miles from Fort Walsh, so they had a nice little journey before their actual work began. Relays of horses were sent to Battleford and Calgary, together with forage and other supplies.

The Commissioner met the Governor General and party at the Blackfoot crossing on the 11th of Sept., where a grand war dance of the Blackfeet had been held, in honor of the visit, and proceeded with the party to Ft. Macleod via Calgary, at which latter place they rested a day or two.

At Ft. Macleod the escort was changed, and Superintendent Crozier took command for the journey south into Montana, the Governor General intending to return east by the United States.

The officer in command of the 3rd U.S. Infantry, Colonel Kent, at Fort Shaw, Montana, situated something over 200 miles south of Ft. Macleod, was notified by Col. Irvine of the Governor General’s intended visit, and the notice was received by him and the officers under his command with the greatest satisfaction. Lt. Col. Irvine and Col. Kent, with an escort of United States cavalry met the Governor General with the escort of mounted police, at the South Piegan Agency, Montana, and the two escorts proceeded together to Ft. Shaw, where the Governor General and the Canadian police were most cordially received and all honors shown them. From this point the Governor General travelled under the escort of United States troops, Superintendent Crozier returning with his party to Ft. Macleod. Altogether the journey from the beginning to the end was most satisfactory, and the behavior of the different police escorts beyond all praise, as the following copy of a letter written on the old escort from Winnipeg to Macleod, will show.

Ft Macleod, 18, Sept., 81

Sir.

I am commanded by His Excellency the Governor General to desire you to express to Superintendent Herchmer his entire satisfaction with the admirable manner that officer has performed his duty while in command of the force of mounted police which has escorted his Excellency from Winnipeg to Ft. Macleod. I am further to request you to convey to the non-commissioned officers and men who formed the escort, his Excellency’s thanks for the services rendered by them while on the march, and the pleasure it has afforded him to witness the discipline and efficiency of the corps.

I have the honor to be, Sir

Your obedient servant,

(Sgd.) F. De Winton, Lt. Col.

Mil.-Secy.

The same thanks were also given to Supt. Crozier and the escort under his command before they returned north from Fort Shaw.

The whole of the Northwest Territories were now beginning to settle, not it is true, with great rapidity, but slowly and surely, and it was becoming evident that the strength of the police force, about 300, was not sufficient for the work they were called upon to do, more particularly as nearly all the Indians had now settled on their reserves. The force was stationed and divided up between thirteen posts, as follows; Fort Walsh, Qu’Appelle, Shoal Lake, Swan River, Ft. Macleod, Blackfoot crossing, Calgary, Macleod Farm, Blood Reserve, Battleford, Saskatchewan, Prince Alberta and Wood Mountain. These different stations were in most cases at long distances from each other, and being so numerous, their strength was very small. The commissioner therefore recommend this fall to the government the necessity of increasing the force by at least 200 men, giving many good reasons for doing so, the most particular being the necessity of protection for the settlers now entering the country against the Indians, and vice versa. I quote a portion of the recommendation as follows:

“Since the beginning of Treaty 7 in 1877, the Blackfeet, Bloods and Piegans have never been even temporarily assembled in Canadian territory up to their full strength. In 1877 it must be remembered that large quantities of buffalo were to be found in the country. The Indians were then self supporting, in fact almost rich, and certainly contented. Thus notwithstanding the fact of these three tribes being nothing less than savages, they were not dangerous. Now matters have completely changed; the savage nature alone remains, and they are purely dependent on the government for a living. The yoke of dependence weighs somewhat heavily upon them. It is true that the policy of settling the Indians on reserves, and instructing them in agricultural pursuits has been adopted; small bands have from time to time straggled in, food homes on the reserves and adopted the new mode of life, but the majority are fresh from the south of the international boundary line, where they have been employed in hunting buffalo. It must be remembered that these Indians have led a lawless and roving life, that they have been accustomed from infancy to regard other men’s cattle and horses as fair plunder, and that the habits of a life time are not easy to unlearn. It is not natural to suppose that they will at once settle down to a quiet, humdrum life, and devote themselves heart and soul to farming. Discontent may, in fact more than probably will, break out, and the spirit of unrest show itself, particularly among the young men, which, if not suppressed in time, will result in periodical raids on the cattle and horses of settlers. This would in a short time lead to acts of retaliation and a serious outbreak would follow as a natural consequence.

“The number of Indians in the Northwest Territories, all under the jurisdiction of the police, may be taken as 27,000. The area of territory is some 375,000 square miles, almost equal to the area of France and Germany combined, or nearly twice that of Spain and Portugal.”

It was also recommended that the fort at Macleod should be rebuilt on another site, as the river bottom on which the old fort stood was fast being washed away by the Old Man’s river. Ft. Walsh was also recommended to be abandoned, as the site was far from being a good one, and the Cypress Hills would never be a farming country, as summer frosts were too prevalent. No settlers whatever had come into that district in the six years the police had been there, and I doubt if in 1881 there was a single settler within a hundred miles of that place. The Canadian Pacific was now creeping towards the Northwest and it would soon become necessary that the headquarters of the force should be on the line of railway as soon as it was built to a suitable point, which would soon occur. During the summer of this year, 1881 the coal mines at the present town of Lethbridge were first opened by Capt. Bryant, working for the Galt company, who had leased the coal seams in that locality from the Canadian government. Capt. Bryant also visited the coal seams on the Blackfoot reserve on the Bow river, and started men cutting timber on the Company’s timber limit in the Porcupine Hills, west of Ft. Macleod, where a saw mill was afterwards erected and timber cut and hauled to the Old Man’s river, at Ft. Macleod, where barges were built and sent down the river to the coal mines, where they were, until the advent of the C.P. Railway, loaded and towed down the south Saskatchewan river.

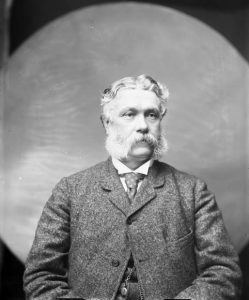

During the stay of the Marquis of Lorne at Calgary I was offered by Mr. Dewdney, the Indian Commissioner who was with the party, the agency of the Cree and Assiniboine Indians at Fort Walsh, which I accepted, together with Mr. Dewdney, proceeded from Ft. Macleod across country to Ft. Walsh after the Marquis had gone south.

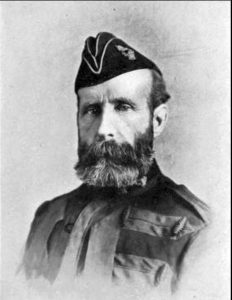

There were about 700 Assiniboine and about 1,000 Crees camped at Ft. Walsh and in the neighborhood, and these were in a very destitute condition. An experimental farm had been started for them on Maple Creek, on the north side of the mountains, but owing to the summer frosts, had not proved much of a success; although some wheat had been raised it had not fully ripened. No beef cattle had been contracted for these Indians, and as there were no buffalo now in that section, it was difficult for them to get a living, which they managed to gain principally by fishing. Some of the lakes in the Cypress Hills were full of fish, principally suckers, and on these they had to live. A great many of the Cree Indians were non treaty, and it was the aim of the government to get them all, both Crees and Assiniboines, away from Cypress, and on to reservations east of the present Regina. They had, however, shown great unwillingness to go, and as the season was far advanced, it was necessary that some provision should be made for them at Ft. Walsh, and with the scanty supply on hand, I and Inspector McIllree, who was in charge of the police at that place, had our hands full. The winter was a very hard one, and the Indians suffered greatly, bacon, a little pemmican, wheat and fish, being altogether their food during the winter, and our work was of the hardest to keep them quiet on these short rations. Too much credit cannot be given the commanding officer and those under him for the manner in which they handled the Indians this winter and kept them quiet. There were many bad characters among the Crees assembled there, such as Lone Man, Little Pine, and many others who took an active part in the rebellion of 1885.

Mr. Dewdney the Indian Commissioner was this winter appointed Lt. Governor of the N.W. Territories, Lt. Governor Laird’s time having expired. Mr. Dewdney at the same time was Lt. Governor and Indian Commissioner, and Mr. E. Galt Asst. Indian Commissioner. It was not until late in the summer that the Assiniboines and most of the Crees left Ft. Walsh, and then they went south along the Missouri river, as they had received word that buffalo were to be found in that direction, and it was with great difficulty that most of them were induced to go on their reserves near Qu’Appelle, but after the payments they again went south after returning all tools etc., that they had received from the government.

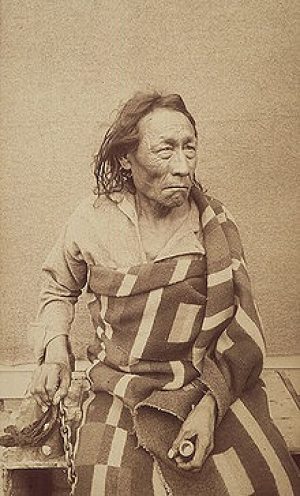

Big Bear and a large following of Crees, all non-treaty Indians, who refused to sign the treaty, as they said they objected to hanging as the punishment for murder, had for years off and on, been hanging round Ft. Walsh, sometimes going south to the Missouri river after buffalo, but always returning to Cypress; these Indians had given endless trouble but in December, 1882, they took the treaty at that place, and went north in 1883, only, however, to foment discord and to join the rebellion in 1885.

Regarding these Indians, the Indian Commissioner in his report of November 1882, remarks:

“The wish of the government that all Indians south, should go north, as, I am sorry to report, been only partially successful, but had Ft. Walsh been abandoned as determined on last winter, I have no doubt the bulk of them now south would have been on their reserves, and some of the restless ones who went north would not have risked returning south as they did. The knowledge that if the buffalo failed, they could fall back on Ft. Walsh, made them visit what would otherwise have been starvation. At one time during the summer it looked as if we should have had a return of the buffalo in large numbers, as several bands were north of the Missouri River, on the Milk River, but the United States troops stationed south of the boundary to prevent the return of the Indians, coupled with the burning of the grass along the boundary line by the American Indians, drove them back, and they are still south of the Missouri river.

“Our Indians who expected to meet buffalo this fall, remained south, and when starvation actually stared them in the face, they congregated round Ft. Walsh. They were in a most deplorable condition and begged to be paid their annuities at that place.”

The Indian Commissioner goes on to report Big Bear being admitted to treaty No. 6, and states that: “Big Bear, who has, I think, borne unjustly a bad character, will make one of the best of chiefs.” This prediction of the Commissioner was far from being realized, as Big Bear was one of the most mischievous and stubborn Indians of the Rebellion.

During the summer of 1882, the Northwest police, which up to this time had been only three hundred strong, was increased to 500 in number and the western posts greatly strengthened thereby. It was time this increase was made, as the Indians were all through the south and west giving a great deal of trouble in getting them to remain on their reserves, and to put a stop to horse stealing in the south, which was becoming very prevalent and giving rise to complaints from the American government. The small force of police had more than they could do, and it was high time that an increase in the strength of the force should be made.

Continued in Chapter 26: Trouble with Blackfeet.

Leave a Reply