The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 12

Continued from The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 11.

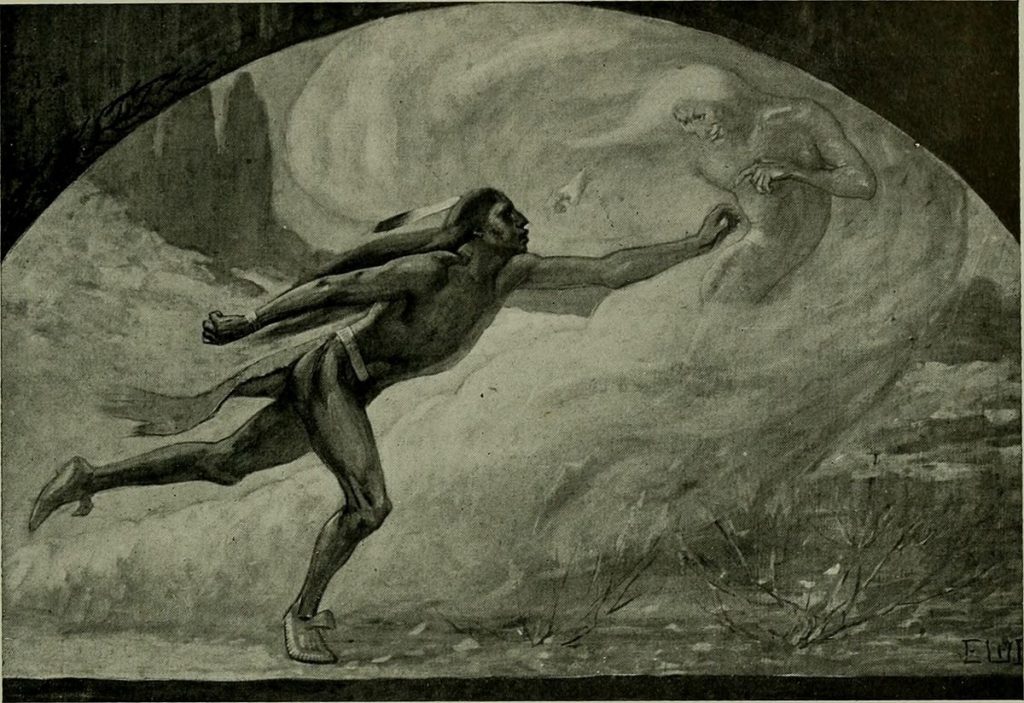

The Cannibal

Henry and his men decided to spend the following winter at Sault Ste. Marie. When it became evident that fishing was poor in the area that winter, they relocated to what is known today as Keweenaw Bay, at the southern end of Lake Superior. During their stay, they were joined by a band of Indians who were similarly fleeing from famine.

Two days after the band’s arrival, a filthy and unkempt adolescent emitting a terrible odour wandered out of the woods. The native told Henry and his crew that his family had been starving, and that he alone had the strength to leave their camp in search of food. “His arrival struck our camp with horror and uneasiness,” Henry wrote, “and it was not long before the Indians came to me, saying, that they suspected he had been eating human flesh, and even that he had killed and devoured the family which he pretended to have left behind.”

Although the teenager denied the charges when questioned, the Indians encamped nearby decided to investigate and followed his trail back to his family’s camp. “The next day,” Henry wrote, “they returned, bringing with them a human hand and skull. The hand had been left roasting before a fire, while the intestines, taken out of the body from which it was cut, hung fresh on a neighboring tree.”

When presented with this evidence, the teenager confessed that he did, indeed, cannibalize his family, which constituted his uncle and aunt and four of their children. Following a failed hunting expedition, his uncle had fallen into depression and asked his wife to kill him. Although the wife failed to comply, the teenager and his eldest cousin decided to carry out the deed instead. The boys murdered their respective father and uncle and ate his body. Shortly thereafter, they did the same to the two youngest children. As the dead man’s widow was too feeble to travel, the boys left her behind and headed into the forest towards Lake Superior. Along the way, the teenager killed his elder cousin and cannibalized him. The body parts that the Indians found by the fire constituted his last remains.

“The Indians entertain an opinion,” Henry wrote, “that the man who has once made human flesh his food will never afterward be satisfied with any other. It is probable that we saw things in some measure through the medium of our prejudices; but I confess that this distressing object appeared to verify the doctrine. He ate with relish nothing that was given him; but, indifferent to the food prepared, fixed his eyes continually on the children which were in the Indian lodge, and frequently exclaimed, ‘How fat they are!’” Fearful that he would attempt to cannibalize their children, the Indians executed the teenager by splitting his head with an axe when his attention was distracted.

The Bay of Michipicoten

Henry and his crew spent the winter of 1766/67 at the mouth of the Michipicoten River on the northeastern shores of Lake Superior. In his memoir, Henry wrote about a cluster of tiny volcanic islands on the eastern shores of the Bay of Michipicoten, off a point known today as Cape Gargantua. The Indians told Henry that one of their legendary ancestors, Nanibojou (sometimes spelled “Nanabozho” today)- which name Henry interpreted as meaning “Great Hare”- was buried beneath one of these islands, and that it was their practice to leave sacrifices like tobacco and kettles to him whenever they passed his resting place. According to an old Ojibwa tradition which Henry was told by his Indian friends, Nanibojou, in ancient times, learned of an impending Great Flood. He built a giant raft on which he housed himself, his family, and all the animals of the world. The Flood came, and Nanibojou and company floated on their raft for many moons. Eventually, Nanibojou created the earth and the human race. Later, when the animals conspired against the human race, Nanijobou took away their ability to speak.

Henry and his men took up residence in an old abandoned French trading post on the shores of Michipicoten Bay and began trading with the natives, who were the impoverished Gens de Terre whom Henry had first met at Sault Ste. Marie back in the spring of 1672. At their request, Henry decided to give these natives goods on credit, knowing that they had a reputation for honesty.

In April, 1767, Henry decided to make maple syrup. To do this, he built a sugar shack, digging through the snow in order to lay its foundation. “The house was seven feet high,” Henry wrote, “but yet was lower than the snow.” Shortly after he returned from this excursion, the Gens de Terre returned from their winter hunting grounds bearing furs for him. Of the two thousands furs-worth of goods he had lent the Indians on credit, only thirty remained unpaid by a debtor who had died in the woods. His family, Henry wrote, “offered to pay the rest form among themselves; his manes, they observed, would not be able to enjoy peace, while his name remained in my books and his debts were left unsatisfied.”

Later that spring, Henry made a trip to Michilimackinac, where he met with a man named Alexander Baxter who had recently arrived from England. When Henry told the newcomer about the natural copper mines he had found throughout Lake Superior, the Englishman suggested that they partner up and form a mining company sometime in the future.

Henry decided to spend the following winter at Michipicoten Bay. In October, while preparations for the winter season were underway, he decided to make a trip to Sault Ste. Marie with three French-Canadians and a young Indian woman who had relatives at the fort. They spent the first night of their voyage on the aforementioned Island of Nanibojou and neglected to make the customary offerings to the ancient patriarch of the Ojibwa people. That night, a violent storm swept across Lake Superior, forcing Henry and his companions to spend several days on the island. The travellers managed to paddle a short distance down the coast before being forced to make camp on the shores of the mainland due to the poor weather. The storm raged on for nine days, stranding the travellers in their campsite. They quickly exhausted their rations and began to go hungry. Two of the French-Canadians plotted to kill and eat the Indian girl, and were disappointed when Henry discovered their plan and put an end to it. Fortunately, Henry shortly discovered some edible lichen on a nearby mountaintop, which the company happily boiled and ate. “It saved the life of the poor woman,” Henry wrote, “for the men who had projected to kill her would unquestionably have accomplished their purpose. One of them gave me to understand that he was not absolutely a novice in such an affair; that he had wintered in the Northwest, and had been obliged to eat human flesh.”

On the evening of the ninth day, the party resumed their journey, many of them drifting in and out of sleep from fatigue. The following morning, they encountered a party of Indians who supplied them with fish. Henry and company immediately paddled over to the shore, built a fire, and enjoyed their first hearty meal in a week.

Continued in The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 13.

Leave a Reply