Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter I: Condition of Canadian Northwest in 1872.

Chapter 2

Ruin of the Red Man

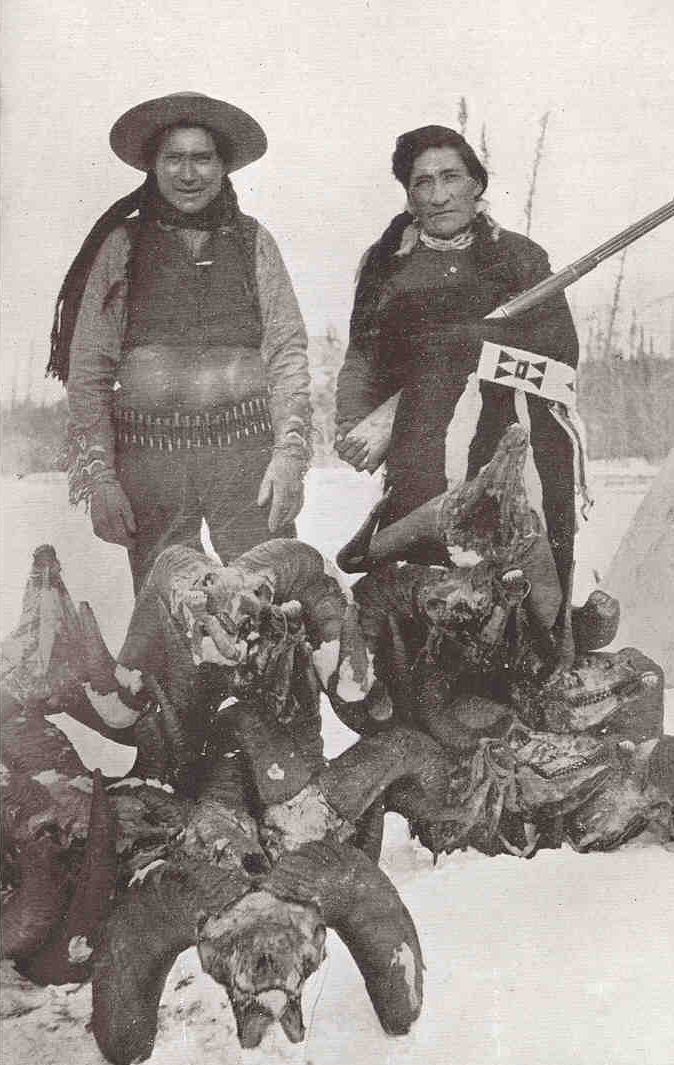

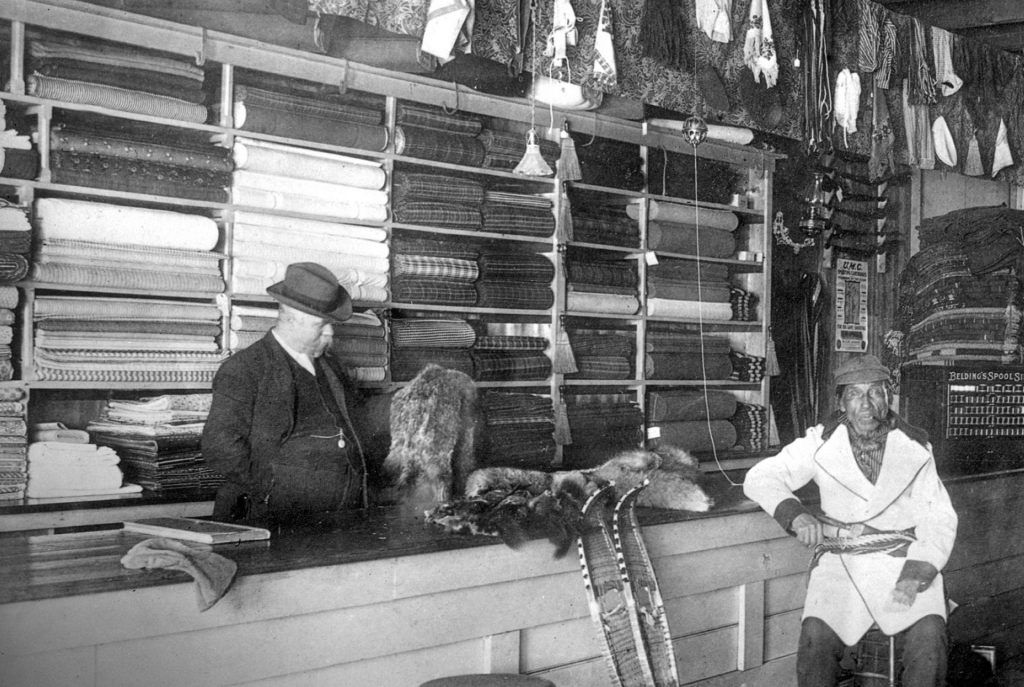

THE TRADE DERIVED from the Stony Indians was a valuable one, consisting nearly altogether of fine furs, such as fox, marten, beaver, otter, and many others.

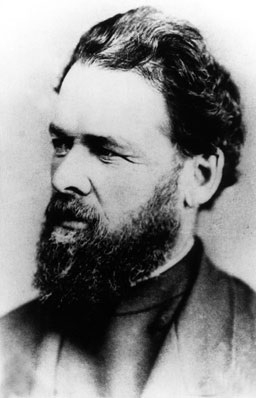

This tribe had for some years been subject to missionary labor, which the plain Indians had not, and it was so far successful that they did not barter their furs for whisky, but confined their trade nearly altogether to the H.B. Co., either at their small post on Ghost river, or at their fort at Edmonton, on the Saskatchewan. A Mission had been built a few years before by this tribe on the Bow river, and at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, and Mr. McDougall, a minister of the Methodist persuasion, had resided some years among them prior to the advent of the police. This gentleman had also at various times visited some of the trading forts in the south, and had been able to observe the terrible effects the whisky traffic was having on those tribes coming into contact with it, and he was not backward with others who had passed through the country in making his voice heard in the east, by urging the Canadian government to take steps at once to put a stop to this iniquitous traffic.

His chances of observation were good, as he had lived many years among the Indians, and in fact partly supported himself and family by Indian trade. He also often went on the plains himself with a string of carts on a buffalo hunt for both meat and pelts. The latter he sent yearly overland to Winnipeg, some 700 miles, returning with a year’s supply of provisions and trading goods.

Other missionaries also were in the country, there being many Roman Catholic priests in the north along the North Saskatchewan river, but it was only on very rare occasions that any missionary visited the south, or any of the trading forts in that country, and no missionary labor whatever had been performed among the wild and fierce tribes of Blackfeet, Bloods, Piegan and Sarcee Indians who roamed the southern plains, they having so far been found intractable and unteachable, and the constant use of whisky had been so demoralizing that it was unsafe for a peaceable traveler to go among them.

A few other travelers had from time to time passed through the southern country with strong escorts, and brought bad reports of what they had heard and seen of the liquor traffic, and such men as Butler, Ross and Palliser had to be listened to.

However, with but few exceptions none of these travelers ventured far on the plains, the road generally taken by them if journeying south, being along the foot of the mountains, they sometimes visiting some of the traders’ posts for supplies, but most of the travel being from Winnipeg, went along the North Saskatchewan, calling at the different H.B. Co. trading posts, such as Ft. Carlton, Pitt and others until their arrival at Ft. Edmonton, from which post they generally took either the Jasper or Yellow Head Pass, through the mountains to British Columbia.

The distance from Ft. Edmonton to the nearest prominent American trading post, which was situated on the Elbow river not far from the present site of Calgary, was about 200 miles; nearly all of the country from 50 miles north of the Bow river being a timber country and the country of the Cree Indians, which Indians had always been bitter enemies of those of the plains, who never came into contact without a battle, although it is true that some bands of Blackfeet would go as far north as Edmonton to trade for articles they could not procure from the American traders, but these always took care to go in large parties, and even then seldom came south again without a collision with the Crees, in which generally many were killed. It was therefore seldom that travelers passed through the plains to the south, and when they were forced to do so, generally took a trail that ran along the foot of the mountains, and thus avoided coming in contact with the Indians who lived far out on the plains. There was therefore not much actual knowledge of the real state of things by individual observation, and for that reason the stories told were if anything far ahead of the real existing state of things.

Fabulous tales began to be told of the mineral wealth of the southern portion of the Territories, its climate, inhabitants and capabilities. Tales were told of Indians from the south trading gold dust and nuggets at the H.B. Co. forts in the north, of the use of golden bullets by the Indians in their old flint muskets, and many other equally astonishing tales, and of course the whisky trade was equally exaggerated, for although it was bad enough, it could not come up to the tales told of it.

We were told of companies of traders, drilled and armed, inhabiting strong forts protected by artillery, which would take a strong force of soldiers to dislodge, and that those traders were growing enormously wealthy from the proceeds of their unholy traffic, having the Indians in almost complete subjection to them.

Of course there was some foundation for these stories, in fact gold had been traded by the Blackfeet at Ft. Edmonton but this gold was the proceeds of the massacre of a party of emigrants, who it is supposed were on their way from the south to Peace river, as many rumors were in circulation in Montana as to the vast richness of the gold deposits in that river, and more than one outfit started out to reach this point who were never heard of again, being in all probability killed by the plain Indians before they left their country.

One instance I know of, that happened not many years previous to the advent of the police, a party consisting of men, women and children, with horses, wagons and provisions, were camped on the Old Man’s river, not far from the present site of Macleod; where they came from, and where they were going was never known, but they were supposed to be on the way from Montana to either Edmonton or Peace river, or were a party of emigrants who had lost their way on the plains. Their camp was visited by many bands of Blackfeet, who professed the greatest friendship for them, but at an unguarded moment they were attacked by Old Sun, a Blackfoot chief, and none were left to tell the tale. What horrible scenes took place can only be imagined, but the whole camp was wiped out as completely as if the earth had swallowed them up. The fair haired scalp of a woman that was for a long time in possession of Old Sun, and some gold dust traded by some Blackfeet at Fort Edmonton, were the only relics of the gruesome tragedy preserved.

Blackened remains of parts of wagons were to be seen long after the arrival of the Mounted Police, on the spot where once these unfortunate people camped.

Other causes that could indirectly be traced to the trade carried on by men from the American side of the line, led to the almost complete demoralization of the Indian tribes on the plains, and increased the stories circulated through Canada.

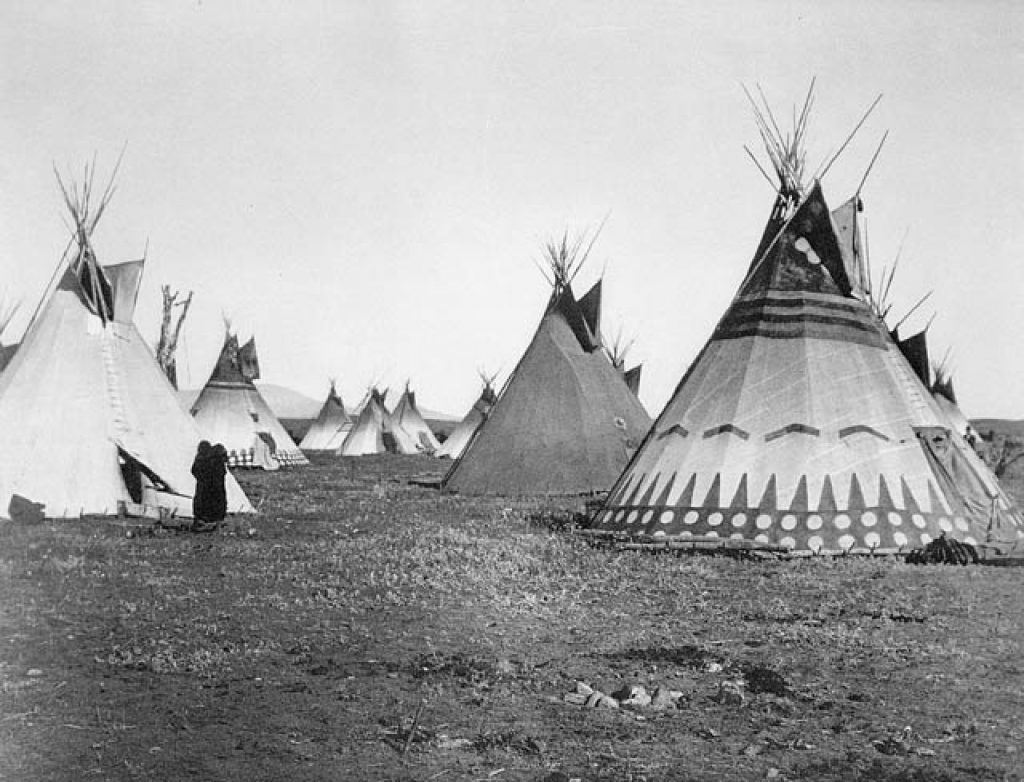

In the years 1870-71 a frightful epidemic of small pox swept off more than a third of the Indians belonging to the plain tribes. In some cases what had been powerful tribes dwindled down to only a few hundred souls. The Sarcees, who previous to the epidemic numbered several thousands, on the arrival of the police could only show three or four hundred. This frightful epidemic came among the Indians originally from the south. It is said by some to have first started at Fort Benton, on the Missouri River, being brought up that river on a steamer. Two men having the small pox were put off the boat at that place, and their clothing was given or traded to Indians after their death. There is, however, no doubt that it first spread into this country from the south. Southern traders were constantly passing between Montana and the North West Territories, and they were in continual communication with Canadian Indians, who also were often visiting American trading forts on the Missouri river. In all probability that was a means of spreading and developing the dread disease among the Indians of the plains.

The small pox was totally unknown to the Indians, who would flock round the trading posts and try and assuage their agonies with liquor, neglecting all cleanliness, and thereby spreading and intensifying the disease. The lodges of whole camps would be left standing on the river bottoms with nothing but the dead bodies in possession, the Indians leaving everything and flying either to the plains or forts for relief.

Doctors there were none, and with small pox and whisky combined, the Indians died off like sheep. They even became so desperate that they would try to spread the disease not only among themselves but among either white men or half breeds. I have been informed of cases where the Indians would pick off he scabs from their own bodies and leave them on the door handles or other places where white men or other Indians would come in contact with them. Their means of doctoring were most primitive, and some of the means they took for relief were almost certain death. A dose of nearly boiling whisky would be taken, and then an Indian in his agony would rush from his lodge, and plunge headlong into the ice-cold water of the river. In the winter they would break the ice and plunge in. This nearly always resulted in death, although to my astonishment I have been told that in some few cases a cure was the result.

The small pox then, combined with the whisky trade, with which it was indirectly connected, went far to cause, the rumors of demoralization among the Indians to be circulated in the east.

In the year 1871 some Indian traders from across the line located a trading post in the Cypress hills, to trade with the Indians in that section. The Cypress hills was in those days a kind of general battleground for the tribes of Indians, Assiniboines and Sioux on the south, Crees and Seauteaux on the north, and Blackfeet, Bloods, and Piegans on the west. Even the halfbreeds that came in large parties from Winnipeg to hunt the buffalo and make pemmican often came into collision with some of these tribes, and bloody battles were the result. The American traders who came to that place in 1871 and remained there during that winter, traded whisky to the different tribes who came there from time to time.

Two Indians belonging to the Seauteaux camp, a branch tribe of the Crees, where found shot dead by their friends, who laid the blame on the traders. They in turn laid the blame on the Bloods, some of which tribe had been in the vicinity. However, this matter was supposed to be settled by the traders who gave the Indians some presents, and even buried the two Seauteaux who had been killed.

A short time after this took place the traders were reinforced by a party of some twelve or fourteen white men from Benton, who, although they came ostensibly after stolen horses, had more or less connection with the traders, and certainly had no love for the Indians. The Seauteaux Indians near the fort were very poor, both in horses and arms, having in reality only half a dozen horses in camp. Their arms consisted of a few flintlock muskets, and bows and arrows. The Indians from the north, such as Crees and Seauteaux were not supplied with repeating rifles. It was seldom that they came in contact with American traders, from whom they could procure these arms. It was, therefore, certain that these Indians had not stolen the horses which the men from Benton were in search of. The stolen animals was supposed to be in the camp of a large party of Crees, some thirty miles away from the fort.

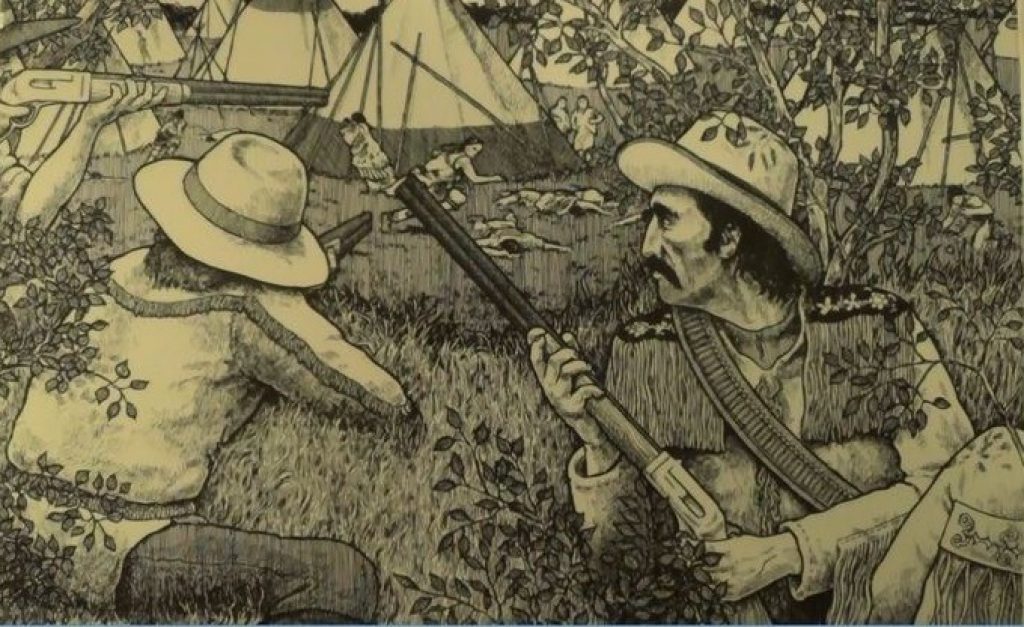

It was claimed by the traders that a Sauteaux Indian came to the fort and then rode off with a horse belonging to one of them. The white men went in a body to the Seauteaux camp to get revenge. They claimed that the Indians fired the first shot, which, however, did no harm. These men then sheltered themselves under a cutbank, and opened on the Indians, who, although they exceeded them in number, could do them little or no harm, as their arms were nothing in comparison to the repeating rifles and revolvers in the hands of the traders. The number of Indians was about 100, old and young, against 18 or 20 white men. The Indians were in the open or in their tents, while the white men were under cover. Nearly 40 Indians were killed, some being women; only one white man was killed. This fight was called the Cypress Hills massacre, and I think, appropriately.

The traders after this fight abandoned their fort, burning it, and went south. Some account of the massacre leaked out and was taken up by men in Montana, who were averse to the wholesale slaughter of Indians. The matter was referred to Washington, it being then thought that the Cypress hills was in American territory. The boundary line had not been run at that time, and in fact was not in that section until three years later. The government at Washington on ascertaining that this fight did not take place in the territory, referred the case to the government of Canada, which government took the matter up. This was another cause of hastening the organization of the N.W.M.P. The result of the trial of these traders some years afterwards will appear in a future chapter.

Continued in Cypress Hills Massacre.

Leave a Reply