Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Chapter 1

Condition of Canadian West 1872

IN AND PREVIOUS TO the year 1872, reports had been widely circulated in Canada, and representations had been made to the Dominion government, that the vast country lying west of Manitoba to the Rocky Mountains, and from the North Saskatchewan to the American boundary on the south, was infested with lawless companies of traders from the territory of Montana, lying south of the line on the American side.

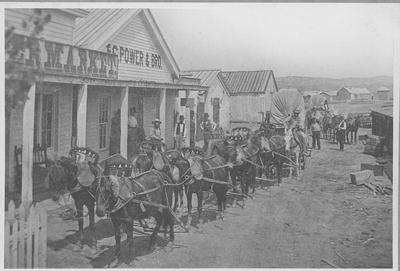

The small town of Fort Benton, on the Missouri River, in that territory was the point of supply to these parties, and outside of the few goods, such as blankets, tobacco, ammunition, etc., their chief stock in trade consisted of liquor, and that of the poorest quality. The objective point of these traders was north of the boundary in the North West Territories of Canada, and the trade was altogether with the Indians residing in that country. The leading firms in the town of Benton were not behind the rest in sending out parties, well supplied with whisky and other goods, to trade in Canadian territory, and in fact today the two head partners in the largest and richest business firms in that state owe their great wealth and good standing, one to two lucky years of whisky trading on Sheep Creek, south of the present city of Calgary, and the other to the same cause, on the Missouri River. This trade of liquor to the Indians had been gradually increasing for many years previous to 1873, in fact ever since the Hudson’s Bay Company put a stop to it in their own trading posts, which trade they had carried on from time immemorial, with immense profits to themselves, but they put a stop to it as soon as they saw that settlement of the country was imminent.

This illicit trade finally assumed such proportions that the American traders on many of the rivers of the present Territory of Alberta had gained such a foothold that they had built themselves forts, and were permanently located in the country, making these forts their headquarters and during the summer months sending parties with trading goods to all parts of the country.

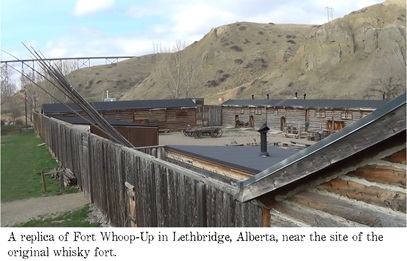

These forts were built of logs, and strongly fashioned, and in some cases the bastions were even armed with cannon of small caliber.

These forts were built of logs, and strongly fashioned, and in some cases the bastions were even armed with cannon of small caliber.

The principal fort of this kind was at the junction of the Belly and St. Mary’s rivers, some 50 miles in Canadian territory, and was named “Whoopup,” the name being derived from the fact that one of the former occupants of the fort who was outfitted by T.C. Powers, of Ft. Benton, was at one time making a good trade, but ran out of whisky; so he sent a messenger to Benton to Powers, to send more at once, as he was whooping it up in his trade, hence the fort took this name. This fort was a rendezvous for all the traders of the country, being a point of supply to all northern and other small trading forts, of which there were many scattered along the different rivers.

This fort was on the direct trail to Ft. Benton, about 200 miles south, and was built as far back as the year 1868 by two Benton traders, Messrs Healey and Hamilton, who took an active part in the trade with the Canadian Indians. Both of these men married Blackfeet women, and their sons and daughters who were sent to school in Montana, are now well married, and can hold their own, as far as education is concerned, with the white settlers among whom they mix.

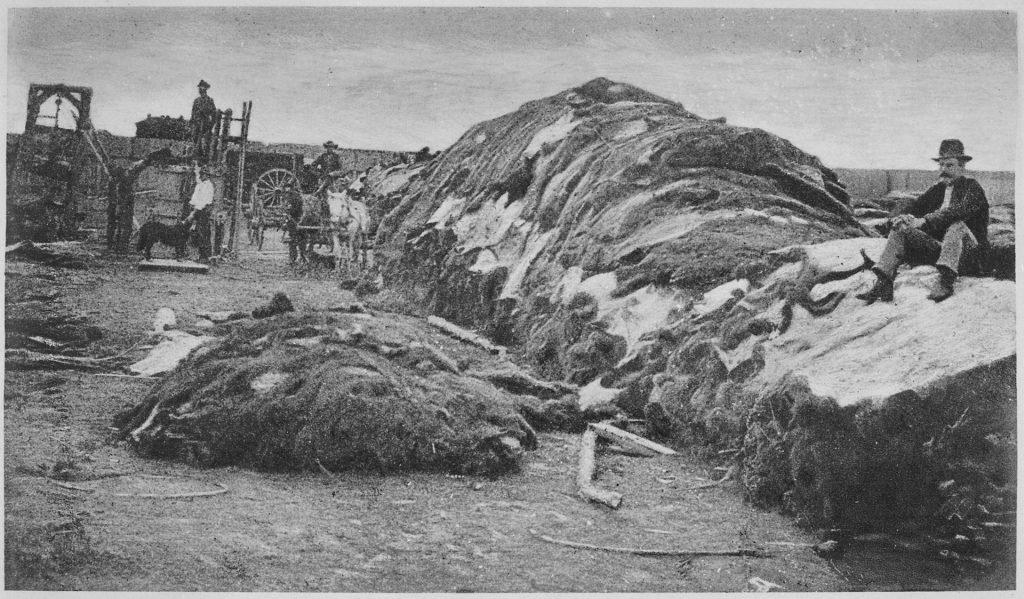

At this particular fort a large stock of whisky or alcohol was always on hand, together with other articles of trade such as blankets, beads, provisions and clothing of all kinds, and in the spring, when the buffalo robes (the chief article of trade) were brought from other outlying forts, being the result of the winter trade, the store rooms were packed to the roof with tens of thousands of these valuable furs, worth from three to as high as ten dollars a piece, according to their quality. A split robe, being one cut down the middle and then sewn together with sinew, was not of near the value of what was called a head and tail, or complete robe, which ranged in price from five to ten dollars.

These robes, the result of a winter’s trade, were then forwarded to Ft. Benton by horse or ox teams, and from there down the Missouri river by the large traders in Benton who had advanced the goods, or liquor, to those in the north, who then loaded their teams with a fresh supply of goods and returned for another year’s trade into Canadian territory.

These traders did not confine themselves to the trade in buffalo robes, but bought from the Indians, horses and anything else they might take a fancy to. The price given in whisky or alcohol was absurdly small; a small cup of diluted alcohol being often traded for a prime robe, which would fetch in Benton from five to seven dollars. Most advantageous bargains were often made with half drunken Indians, who, when in that state, would sell anything they had for more whisky.

Hundreds of horses were thus bought, but not always with such profit to the trader, who, had he confined his trade to robes alone, which could be safely stored away in the forts, his trade would have been comparatively safe, while horses had to be herded, and many a watchful eye was on them as long as they remained in the country, and it was a common thing for Indians to run off large bands of horses, not only those they had themselves traded, but often those belonging to the traders themselves. These raids were even made as the trains loaded with robes were on their way south, and constant vigilance had to be exercised in watching the bands at night, and in all weathers, as the more stormy it was, the greater danger of their being run off.

No mercy was shown to skulking Indians, who were shot on sight, and as these parties going south with their winter’s trade consisted often of as many as twenty men, serious fights often took place in which many were killed, the Indians general the losers, owing to the white men being well armed with repeating rifles, while the Indians at that time had little else but flintlock muskets, or even bows and arrows.

It was not until some years after that repeating rifles and fixed ammunition were general among the plains Indians, when many more traders came north to reap the rich harvest to be gathered in the Indian trade.

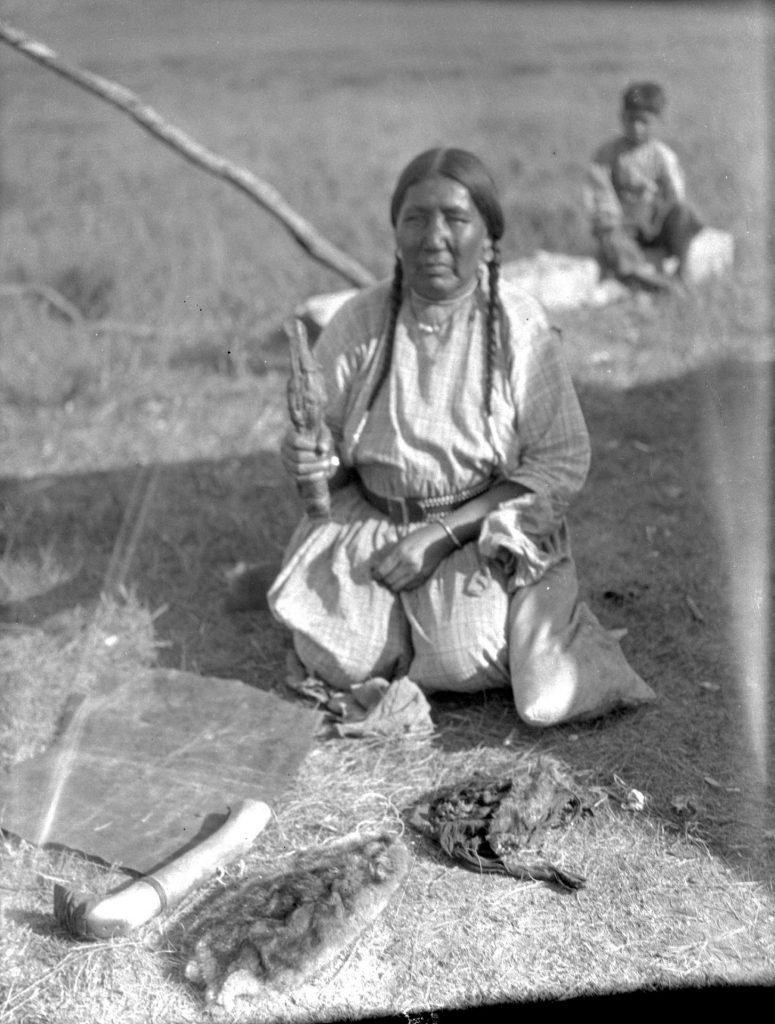

When the Mounted Police came into the country, the Blackfoot were nearly all armed with repeating rifles, as the whisky trade had become a recognized business with hundreds of men from the south, and rifles and ammunition were traded as well as whisky, and permanent trading posts had been established. The Indians had such a craving for liquor that not only did they sell their robes and horses, but also their women, and I doubt if there was a trader in the country who did not have from one to three squaws, bought for liquor.

One instance I remember, of an old whisky trader informing me that the squaw he then had was Number 57, bought by him at different times from Indians during his career as a trader in the country.

These traders then held the Indians in almost complete subjection, not on account of any friendship the Indians had for them, as they would take any and every opportunity to raid and kill any small party or single individual found away from the trading posts, but by the almost ungovernable passion the Indians had for liquor; their greatest chiefs and bravest warriors would crawl on the ground and give up all they possessed for a cup of whisky, and as the American traders were the only ones from whom they could procure this liquor, and as the traders allowed only a limited number of Indians to trade at a time, the Indians would do all they could to encourage them to remain among them, and in but few cases would have wished them to leave.

Also as nearly all these traders had married Indian women, according to the Indian custom, that is by purchase, and in many cases, the women were connected with some of the leading chiefs, they had a certain influence through these women with the Indians themselves, for, strange as it may seem, the women in most cases became attached to the white men with whom they lived, and used their influence in the tribe for the benefit of their husbands, and in many instances would undertake to trade whisky in the camps in making a sharp bargain for their masters.

The system of whisky trading had gradually demoralized and to a great extent decimated what at one time were large and powerful tribes (not only as far as numbers were concerned) and had taken the courage and spirit out of what remained, so that their former active and healthy mode of life was gradually being superseded by a loafing, half-drunken existence, the men only hunting to supply themselves with what meat they required, and to get robes enough to buy them the required amount of liquor and other necessities.

This was all the more easy as they had acquired the new firearm which was a hundred times more destructive than the old flintlocks or the bows and arrows, and therefore the amount of exertion required to kill the buffalo, which still roamed the plains in immense herds, was greatly lessened, and the number killed much larger, with less exertion, and the old time hunts were turned into a slaughter.

As the traders multiplied in the country and whisky became more plentiful, the Indians could procure more of it and in consequence many more robes were traded, each year tending to the destruction of the buffalo.

The result of this trade on the Indians, as I have before said, would lead them towards complete extinction if not put a stop to.

The gradual extinction going on was caused by the liquor trade both directly and indirectly.

Indirectly, as regards the numbers killed in their drunken fights, as often a whole camp would get drunk, and the trader was careful to leave before that climax was reached, and the Indians in these debauches would act more like wild beasts than human beings, and during its progress often was many as a dozen men, women and children would be killed, old grudges were remembered and only wiped out by the death of one or more.

Diseases spread among the tribes unknown to them before, and many died from such causes.

It will be understood that the liquor trade was confined to the south and southwest only, and principally among the plains Indians, as the H.B. Co. had withdrawn their trading posts from this section, confining themselves form the North Saskatchewan, northward and eastward, and when the Mounted Police came into the country they had only one small trading post south of the North Saskatchewan, it being on a small river near the mountains, about 30 miles west of the present city of Calgary, and this post was for the purpose of catching the trade of the small tribe of Stony Indians, a branch of the Assiniboines, who confined themselves to hunting in the mountains, and seldom went on the plains, they being at war with the Blackfeet. The Hudson’s Bay Company had given up the liquor trade some years before the advent of the Mounted Police.

Continued in Ruin of the Red Man.

Leave a Reply