Exactly 73 years ago, on June 11, 1945, two Indian trappers drowned in the headwaters of the Wapiti River in the British Columbian Rockies somewhere between Prince George, BC, and Grande Prairie, Alberta. These men, named Archie Belcourt and Josie LeTan, hailed from the tiny community of Rio Grande, located about 95 kilometres to the northeast. Tasked with guiding a survey party, they attempted to cross the Wapiti on horseback and were swept from their mounts by the spring current. Although the survey party searched for their remains, no trace of their bodies could be found.

The Dream

About a month later, a Beaver Dene Indian widow from the Horse Lake First Nation Reserve, located nearly 150 miles away from the site of the drowning, had a strange dream. She dreamt that she was in a canoe on a river in the middle of the wilderness. The man paddling the canoe was a guide whom her late husband had known in life. And in the bow of the canoe, guiding the paddler, was the ghost of her husband himself, who had drowned in the Wapiti many years earlier, in a similar manner to Belcourt and LeTan.

After a day on the river and a night under the stars, her husband’s spirit led her to a particular section of the riverbank. There, close to shore and out of the water, sprawled a human corpse. Her husband then took her to the opposite shore, where another body was entangled in a pile of driftwood.

The Search

Josie LeTan’s widow heard of this dream and asked the woman who experienced it to help her search for her husband’s body, which she believed the woman had been led to. Although the woman had never been to the Wapiti, she agreed to help. She insisted, however, that the paddler from her dream row the boat.

On the woman’s advice, the party started their search at the site of the drowning and paddled downriver. After a day on the water, they made camp on the riverbank in accordance with the Indian woman’s instructions. They continued down the river the next morning and paddled for most of the day. At around dusk, the Indian woman suddenly exclaimed: “This is the place I saw in my dream.”

The party headed over to the shore, where they found a skeleton. Although the wolves had been there first, the party was able to identify the body as Belcourt’s from a large metal belt buckle they found nearby. Some distance downstream, on the opposite side of the river, they found the half-submerged body of Jose LeTan wedged between two logs.

The remains of the two men were transferred to Rio Grande. Funeral services were held in the Rio Grande Roman Catholic Church on August 9th, and the bodies of Archie Belcourt and Josie LeTan were interred in the Rio Grande Cemetery, where they remain to this day.

Clairvoyance on the Canadian Frontier

The Problem with Rationalism

Ever since the 18th Century Enlightenment, Western thinking has been dominated by rationalism- the idea that our perception of truth ought to be defined by reason and the scientific method as opposed to emotion or divine revelation. This way of thinking has benefited mankind enormously. Under the pressure of rationalism, despotic monarchies have given way to democratic republics characterized by freedom and equality under the law (in theory, at least!). Medieval medical techniques like bloodletting and fecal ointments have been eclipsed by effective treatments like vaccines and antibiotics. Enlightenment thinking paved the way for technological advancements which have allowed us to work more efficiently, explore the world and beyond, and generally enjoy a better quality of life than our ancestors could even dream of.

For all the tremendous good it has done us, rationalism is not without its shortcomings. The idea that we can come to a complete understanding of reality through reason alone hinges upon the assumption that we human beings are equipped with the tools necessary to perceive and comprehend everything that is real. But just as an insect lacks the equipment to comprehend things like music, math, and spoken language, perhaps we humans lack the capacity to comprehend all reality via the narrow prisms of reason and our five senses through which we view the world. In other words, there are probably some facets of reality which we may never be able to fully understand or explain through reason alone.

Second Sight

One mystery which defies rational explanation is a phenomenon called ‘Second Sight’. Second Sight is a supposed extrasensory perception, or ‘sixth sense’. People endowed with Second Sight are said to have the ability to receive information, usually through dreams or visions, of distant or future events. They have no control over these visions, which come upon them unexpectedly. More often than not, these visions are distressing, as the information they contain frequently involves the death of someone known to the seer.

It has been suggested that there is a higher prevalence of Second Sight among members of certain ethnic groups. This ‘gift’ is most often associated with Gaels of the Scottish Highlands, who call it “Da-Shealladh,” or “Two Sights”. It is also known throughout the rest of Scotland, as well as in Ireland, Wales, Cornwall- regions of the British Isles with high populations of ethnic Celts.

According to Celtic-American writer Barry R. McCain, “The Second Sight is thought to be hereditary and it ‘runs’ in some families. As is often the case in genetics, the Second Sight may skip one or two generations, and then return, like some regressive trait for hair colour or shape of ears. The phenomenon is much too authenticated to pretend it does not exist.”

Clairvoyance in Northern Canada

Another ethnic group which may be similarly blessed with this gift of prophecy are the Dene of Northern Canada.

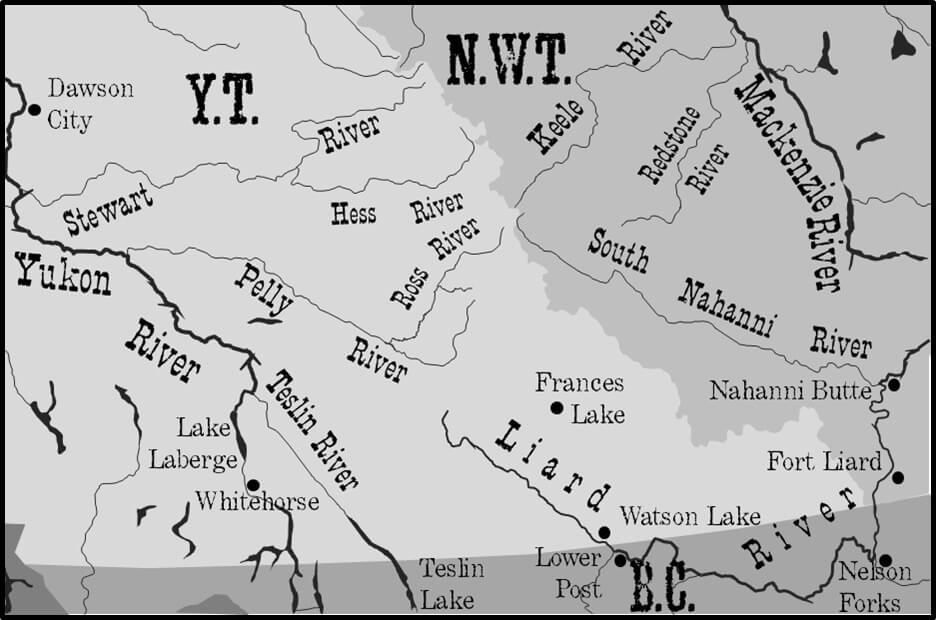

United by ancient blood ties and a common language family, the Dene, also known as ‘Athabascans’ or ‘Athapaskans’, are a First Nations ethnic group comprised of roughly 21 different tribes. Historically and currently, most Dene live in Northern Canada and Alaska, from the Arctic Circle to the boreal forests of the Western Provinces. Archaeologists believe that these people’s ancestors crossed from Siberia to Alaska via an ancient land bridge 10-12 thousand years ago, a millennium after the proto-Indians (the ancestors of most other Amerindians), yet several thousand years before the Thule people (the ancestors of the modern-day Inuit).

To the best of this author’s knowledge, few parapsychologists (as students of extrasensory phenomena are known) have explored a potential connection between Second Sight and the Dene people. Judging from a handful of stories from Canada’s Northern frontier, however, perhaps they ought to.

Poole Field’s Story

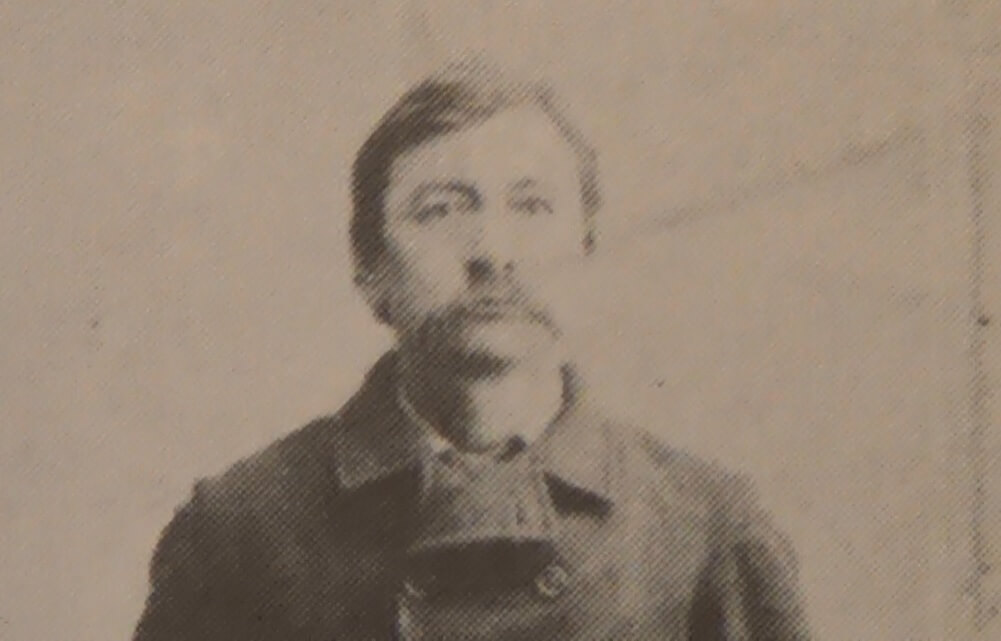

One of the first northerners to write about Second Sight among the Dene was a Canadian frontiersman named Poole Field. Poole Field began his career in the Canadian North as an officer of the North West Mounted Police- the precursor to Canada’s famous RCMP. He cut his teeth in the Klondike Gold Rush, serving under the famous Mountie Sam Steele. Following his honourable discharge from the Force in 1900, Field travelled extensively with the Mountain Indians- a Dene tribe from the Mackenzie Mountains in western Northwest Territories. His travels often took him through the notorious Nahanni Valley, an area in which he had some of his most exciting experiences. Eventually, Field established a trading post at the confluence of the Pelly and Ross Rivers, in Southeastern Yukon, from which he sold goods to the local Dene in exchange for furs.

Poole Field wrote about his adventures with the Dene in letters to his friend John “Jack” Moran, a former government inspector of the Northwest Territories and the Yukon. In one of his letters, Field remarked that Dene medicine men were said to have “the power of a kind of second sight”. Sometimes, they received prophetic visions in their dreams, which all Dene took very seriously. On other occasions, Dene shamans sang themselves into a sort of trance. When they recovered from this dream-like state, they were able to foretell the future.

The Little Doctor

One incident which Poole Field recounted in his letters involved a reclusive Kaska Dene shaman from eastern Yukon, whom everyone called the Little Doctor. “He had about the biggest reputation as a doctor amongst the Indians,” wrote Field, “but would never come down to the store, always stayed out in the bush and would send his sons in with the furs.” In the spring of 1908, Field finally persuaded the esteemed medicine man to visit him at his trading post at Ross River. It would be Little Doctor’s first real taste of the white man’s world.

The Late Shipment

Several days before Little Doctor’s arrival, another band of Dene Indians paid a visit to Field’s store. These natives had come to trade their season’s take of furs for tea, ammunition, and other goods. Unfortunately, Field was fresh out of stock. Several weeks earlier, his partner had taken their steamboat down the Pelly and further down the Yukon River to Dawson City in order to purchase new supplies. He had failed to return on schedule, and Field had no idea what had befallen him. The Indians decided to pitch their teepees beside the post and wait for the shipment to arrive.

When Little Doctor finally arrived at Field’s trading post, one of Field’s native clients suggested that they ask the medicine man to see what had become of Field’s partner. “Well,” wrote Field, “I didn’t have much faith but it could do no harm so I took some tobacco as a small present and went to his camp and told him I was worried about my partner and to see what he could do about it.” Little Doctor said that he would do his best, but was unsure whether or not his medicine would work in this unfamiliar territory.

The Prediction

The following morning, Field paid a visit to Little Doctor’s teepee to see how he had made out. The medicine man claimed matter-of-factly that Field’s partner’s boat was a long way away, but that a band of strange Indians was also approaching the store from another direction and would arrive shortly after the boat did.

When Field inquired as to how the medicine man knew this, Little Doctor explained that, in a dream the previous night, he had been hunting on the side of a mountain not far from Field’s store. He spied a herd of mountain sheep and approached them cautiously, careful to not let them catch his scent on the wind. Despite his efforts, the sheep all stuck up their heads as if they were scared of something and looked down the Pelly River. Frightened of what they saw, they ran further up the mountain before stopping again and looking upriver. Frightened of this second menace, they ran further up the mountain and out of sight.

When Little Doctor looked downriver to see what had scared the sheep in the first place, he saw nothing. “Of course,” the Indian told Field, “you know that a sheep’s eyes are much better than ours.” Little Doctor maintained that the sheep had probably seen Field’s partner approaching, as that is who he had endeavoured to dream about before he went to sleep.

The menace that the sheep saw upriver, Little Doctor said, was likely a band of approaching Indians. They were a little farther off, as the sheep had to climb a little higher up the mountain before they saw them.

The Father of All Dreams

When neither Field’s partner nor the strange Indians arrived by late June, Field sought out Little Doctor once again and asked him to try to assess the situation for the sake of his Indian guests, who were getting anxious. The medicine man agreed.

Early the following morning, Field awoke to discover that the entire Indian camp was up and waiting for him. Little Doctor, it turned out, had awakened that morning from what Field described as “the father of all dreams”.

In his dream, Little Doctor went down the Pelly River in search of Field’s partner’s steamboat and found it “tied up for the night at the mouth of a large creek entering the Pelly from the north.” The medicine man boarded the steamboat and saw that everyone was asleep. The boat was piled to the roof with a very heavy load of freight.

In order to be able to describe the location upon waking, Little Doctor inspected his surroundings. He saw that an old abandoned log cabin rotted beside the creek not far from the steamboat. He went up the creek and followed it all the way to its headwaters, which proved to be two large lakes abundant in fish.

Little Doctor returned to the Pelly and travelled back upriver. Along the way, he found a man loaded down with freshly-dressed moose meat who was heading in the direction of Field’s store. Further up the river, after passing Field’s trading post, he saw a band of strange Indians with six huge moose-skin boats, who were also bound for Ross River.

The Steamer

Word of Little Doctor’s prediction soon spread to the other side of the Pelly, where Poole Field’s rival operated his own trading post. Soon, Field’s competitor and a handful of prospectors made a visit to Field’s post, where they “kidded the Indians about their medicine man” and placed bets that Field’s partner would not arrive for at least several days.

That morning, at around 11 o’clock, a man arrived at the trading post from downriver carrying a pack of moose meat. The Indians were certain that this was the man from Little Doctor’s dream. The man told the delighted natives that he had passed a steamer downriver, and that it was also headed in the direction of the trading post.

Sure enough, a steamer arrived at Ross River later that day. As it turned out, the boat belonged to Field’s competitor. “It was the wrong boat…” wrote Field. “Lots of gloom on our side…Too bad, of course, the old doctor had never seen a steamboat before, and how as he to know the difference? In any case, he had come pretty close to being right.”

Vindication

Field had bet $20 on Little Doctor’s prediction coming true, and would now have to pay his rival, who had bet against it. As he watched his competitors unload their cargo, lamenting his loss, the old medicine man approached him and told him he was sure this steamboat was not the one he had seen in his dream. “For one thing,” the Indian said, “the boat I was on was much lower in the water and the stove pipe was all black. This one is yellow with a black top. Then there is more white men on this boat and no Indians. [On] the other boat there is two Indians as well as white men.”

With fresh wind in his sails, Field asked his Dene clients if some of them might head downriver to see if they could find his partner’s steamer. The creek that Little Doctor described in his dream, at the mouth of which the steamer had been anchored, could only be Orkey Creek, which flowed into the Pelly about 20 miles downriver. Immediately, twelve Dene hunters piled into a moose-skin canoe and paddled down the Pelly.

Neither the hunters nor the steamer returned that day, and Field and his Indian guests retired for the night in poor spirits. Suddenly, at around 2:00 A.M., there was a knock on Field’s cabin door. Field unbolted the door and opened it. To his pleasant surprise, he found himself face to face with his partner. “He had walked up overland,” Field explained, “and everything was exactly as the old doctor had said… That boat landed at eleven that morning and [Indians from the Liard River] arrived that evening with six moose-skin boats, much to the disgust of the other parties.”

The Moccasin Telegraph

Another sourdough to write about native clairvoyance in Northern Canada was a woman named Jean W. Godsell. Jean was the wife of Philip H. Godsell, a Hudson’s Bay Company inspector-turned-fur trader who wrote many excellent books and articles on northern Canadian history. In the September 1954 issue of the magazine FATE, Jean Godsell wrote an article entitled “The Moccasin Telegraph”. This piece detailed a strange event which Jean witnessed in the winter of 1922, at Fort Fitzgerald in Northeast Alberta.

Earlier that year, in the fall of 1921, Jean and her husband watched a Chipewyan Dene band disappear into the wilderness for another season of trapping. Jean wrote:

“I felt a deep compassion for the daughters of the Chief, Marie and Therese Cheesie, as they staggered and slipped down the muddy bank to their canoe. They were toting bundles and bales heavier than their own slim bodies. Motherless tots, of six and seven years respectively, they were being taken into the wilderness to help their father with the daily chores of his life as a hunter and trapper.”

Jean expressed her sympathy for the little girls to her husband. “It’s tough,” the sourdough replied, “but it’s part of their life!”

John James Daniels’ Prediction

One morning that winter, when Jean was thawing out a loaf of bread over her cast-iron stove, a Dene interpreter named John James Daniels burst into her cabin. “Injuns,” he exclaimed, “dey come today!”

Jean was puzzled, as no one had visited the fort for weeks. “How do you know, John?” she asked.

“Me know,” the interpreter said cryptically. “Dey have plenty bad luck, too. Dem come before de sun reach here.” With these last words, he pointed his finger straight into the sky.

The Visitors

Sure enough, shortly before noon, an RCMP constable named Bob Baker dropped by and asked Jean if she would like to accompany him on a hike to the Slave River. “Some Indians are coming from the direction of Dog River,” he informed her. “Let’s see who they are.”

Mystified, Jean slipped on her parka and snowshoes and accompanied the Mountie to the riverbank, where a band of local Chipewyan women were congregated. There, in the distance, she saw the serpentine figure of a dog team heading towards them, mushing over the frozen river ice.

Jean peered more closely at the newcomers and noticed that something was amiss. The dog team had no driver. Suddenly, to her horror, Jean made out two tiny fur-clad figures struggling through the snow at opposite ends of the train. One of them stumbled along behind the sled, while the other trudged ahead on snowshoes, breaking a trail for the dogs. They were Marie and Therese Cheesie, the little daughters of the Chipewyan Chief, and the load strapped to the sled was their father’s frozen corpse.

Howling with grief, the local native women helped the little girls to their teepees and ministered to their blackened, frostbitten faces. Astounded, Jean Godsell looked over at John James Daniels, who had predicted the Indians’ arrival.

“Cheesie,” the interpreter told her in a hushed voice, “him die ‘way out in de bush eight sleeps to the eastward. Dem kids, dey tie ‘im on de sled an’ trek 150 miles through de woods to bring ‘im to de fort so de mission people can bury ‘im proper… I told you, Indians- dem come today!”

“But how did you know?” asked Jean.

“Last night I had a dream,” the interpreter replied, shrugging his shoulders. “Saw everything, just as now.”

The Incident at Fort Churchill

Later on in “The Moccasin Telegraph”, Jean Godsell described another incident of native clairvoyance in the Canadian North. “Some years ago at Fort Churchill, in Northern Manitoba,” she wrote, “another Indian’s prophetic dream came true.”

Much like Poole Field in his story about Little Doctor’s prophecy, the factor of Fort Churchill- a man named Ashton Alston- was waiting for a long-overdue shipment of trade goods. These supplies, on which the fort’s employees and their Indian clients very much depended, came once a year from the Hudson Bay Company’s storehouses in England. In order to keep his Indian clients from going hungry in the interim, Alston issued them free gunpowder and bullets with which they could hunt caribou on the coast.

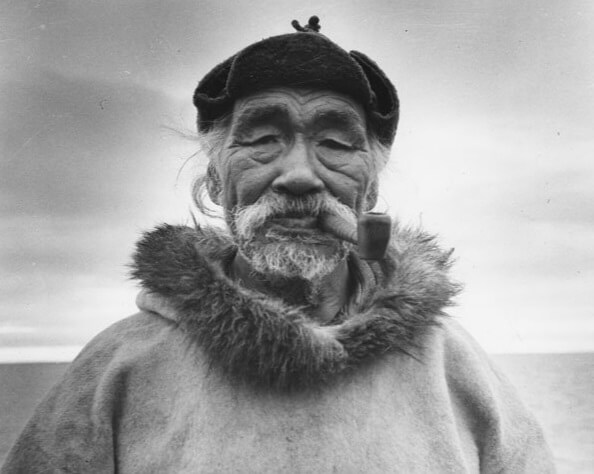

One day while waiting for ship from England, Alston received an unexpected visitor: an old Indian medicine man named Shonkelli. Dressed in fringed leggings and a blanket capote, the leather-faced shaman wandered into the trade room, squatted on the floor, and lit up his pipe.

No sooner had the old Indian begun to smoke than Inspector Tremayne of the Hudson’s Bay Company, another of Alston’s visitors, stormed through the trade room door. The delayed shipment was making life miserable for the Inspector, who had come to Fort Churchill to supervise the transfer of supplies. He said as much to Ashton Alston as he strode anxiously about the room.

Shonkelli’s Predicition

When Tremayne wondered aloud what had become of “that confounded ship,” Alson suggested that they ask the old medicine man. Much to the disgust of Mr. Tremayne, who did not believe in the possibility of clairvoyance, the factor asked Shonkelli for his assistance and offered him a few plugs of tobacco as payment. “But the old Indian was not to be tempted lightly,” Jean Godsell wrote. “Not till his ‘fee’ had assumed considerable proportions did he agree to commune with the spirits and find out what had become of the missing ship. Picking up the tobacco, he slipped silently from the store and headed for his caribou-skin wigwam, where he went into a trance. At sundown, he returned.”

Shonkelli told the Company men that he had sent his spirit body out over the water. The ship, he declared, was safe, and would arrive the following day. It was delayed because her crew had decided to rescue a party whose own ship had foundered in the ice-choked waters of Hudson Straits. After rescuing these men, the Company men suffered a tragedy of their own: one of their members, who wore clothes like a woman, died and was buried at sea.

The Ship

The following day, the Hudson’s Bay Company ship indeed arrived at Fort Churchill, just as the old Indian had predicted. Alston and Tremayne boarded the vessel and learned the cause of the day from its Captain Mack.

While heading through Hudson Straits, the ship’s crew spotted a handful of men marooned on an ice-floe. They rescued the unfortunates, but were trapped by heavy pack-ice in the process. When they finally managed to liberate themselves from their icy prison, one of their members fell overboard and drowned. This man was a black-robed priest bound for the Mission at Chesterfield Inlet in what is now Nunavut.

Shonkelli’s prediction, it seemed, was fulfilled in detail.

Other Cases of Clairvoyance on the Canadian Frontier

Canadian frontier lore is riddled with similar anecdotes of First Nations clairvoyance, not all of them experienced by people of Dene ethnicity.

Jerry Potts

For example, Jerry Potts, a legendary Scots-Blackfoot frontiersman who guided the first Mounties across the Canadian plains, is said to have had a truly uncanny sense of direction. In the words of Mountie Sam Steele:

“He never talked with others when he was at work. He would ride on ahead by himself, keeping his mind fixed on the mysterious business of finding the way. He was never able to give any clear explanation of his method. Some mysterious power, perhaps a heritage from his Indian ancestors, was at work.”

Piapot

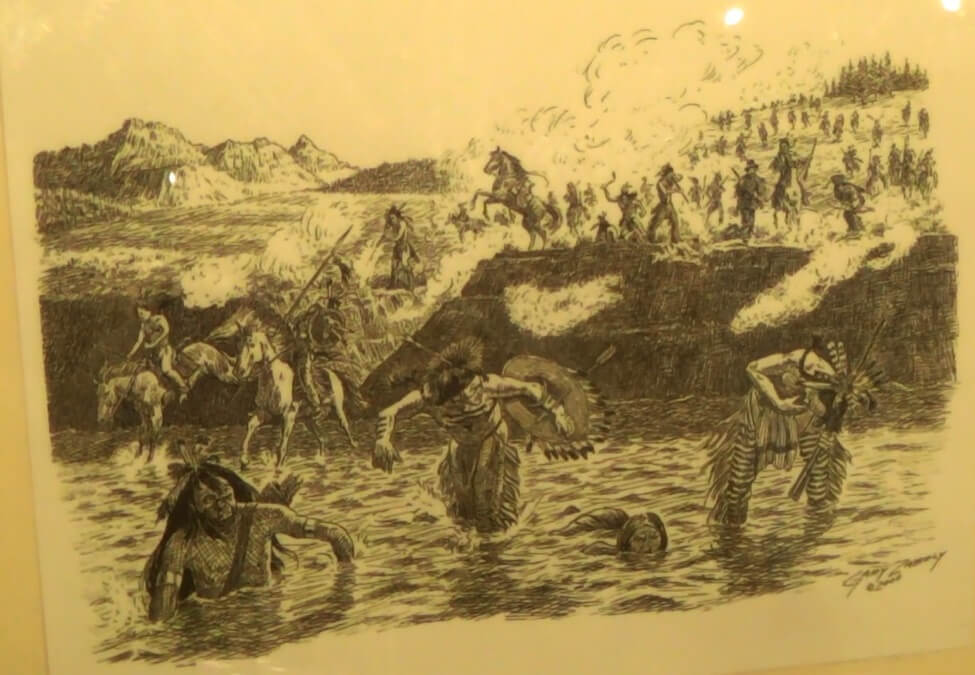

Another Indian of the Canadian prairies to experience episodes of clairvoyance was Piapot, a great Cree-Assiniboine chief.

In the fall of 1870, Paipot and a handful of Cree and Assiniboine chiefs assembled a massive war party and headed into what is now Southwestern Alberta, determined to strike a crippling blow to their enemies, the Blackfoot. One night, Piapot had a dream in which his fellow tribesmen were gored and trampled by a buffalo bull with iron horns. Certain that this was an omen portending defeat at the hands of the Blackfoot, Piapot decided to withdraw from the upcoming campaign and urged the other chiefs to do the same. As the Cree believed themselves to be far more numerically superior to the Blackfoot band they had targeted, however, most ignored Piapot’s dream and continued westward.

The following day, the Cree clashed with a Blackfoot war party that was many times larger than they had expected. The ensuing skirmish is known as the Battle of Belly River. The Blackfoot completely routed the Cree and slaughtered many of the retreating warriors, much like Piapot had predicted.

Ootek

In his book Never Cry Wolf– an account of his experience observing wolves in the Keewatin Barrens of what is now Nunavut- Canadian biologist and writer Farley Mowat described an Inuit shaman named Ootek, who paid the occasional visit to his camp. Mowat related one instance in which Ootek predicted the arrival of a caribou herd with astonishing accuracy. On another occasion, the medicine man predicted the arrival of a party of Inuit hunters, accurately estimating their number before they arrived. The medicine man informed Mowat that he received this information not in dreams, but rather from listening the wolves, whose language he had come to understand.

The Hayward Murder Case

And then there is the strange story of the Hayward murder case in Northern Alberta and the dream which led to its resolution… but that’s a story for another time.

Tell Us Your Stories

Do you know any other tales of clairvoyance in Canada and beyond? Let us know in the Comments section below!

Sources

- “Indian Woman Has Revealing Dream”, in the December 1945 issue of the Alberta Folklore Quarterly, by the Edmonton Journal

- Letter from Poole Field to John “Jack” Moran, July 14, 1939

- “The Moccasin Telegraph”, in the September 1945 issue of the magazine FATE, by Jean W. Godsell, courtesy of Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- Never Cry Wolf, by Farley Mowat, 1963

Leave a Reply