The Monster of Partridge Creek

A Dinosaur in the Arctic?

For as long as we have been aware of their existence, people all over the world have displayed an intense fascination with dinosaurs. Discoveries of their fossilized remains likely helped inspire the legend of the dragon- the monstrous, sometimes-winged reptile which features in traditional folklore from China to Mexico. The wild popularity of the Jurassic Park franchise demonstrates our enduring interest in these kings of the Mesozoic and our deep primitive gratitude that they no longer walk the earth. And many young boys and girls go through a dinosaur faze characterized by an all-consuming obsession with these primordial monsters.

Victorian Dinosaur Mania

The academic community in North America and Europe went through its own dino faze in the mid-to-late-19th Century, after English paleontologist Sir Richard Owen, in 1842, first used the Greco-Latin compound word “dinosaurus”, or “terrible lizard”, as a denotation for the giant ancient reptiles whose petrified skeletons were being unearthed in England, Holland, and Germany. Victorian dinosaur mania veritably exploded a decade later, when Owen commissioned British sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins with creating life-sized sculptures of thirty-three dinosaurs, which were based upon Owen’s interpretations of the handful of fossils that had been unearthed at that time. The sculptures were completed in 1854, and were unveiled with great pomp and ceremony during the grand opening of a prehistoric-themed park constructed outside the Crystal Palace (the Crystal Palace being a portable glass and iron building which had housed London’s Great Exhibition, the first world fair, back in 1851). Catalyzed by the popularity of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs, museums across Great Britain and the United States raced to populate their display rooms with the largest and most impressive dinosaur skeletons money could buy, which they purchased from independent and fiercely competitive paleontologists.

Living Dinosaurs in Victorian Fiction

Hand in hand with the dino-mania of Western academia came fictional tales of lost worlds inhabited by the primeval monsters that had inflamed Victorian imagination. In 1864, French novelist Jules Verne published Journey to the Centre of the Earth, a French literary classic in which an eccentric German scientist and his nephew discover a subterranean ocean deep beneath Iceland teeming with aquatic dinosaurs. In 1888, Canadian writer James De Mille’s fantasy romance, A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, was published posthumously in serial format in the Harper’s Weekly magazine, telling the story of a thermally-heated, semi-tropical oasis in Antarctica where dinosaurs roam. In 1898, English novelist C.J. Cutliffe Hyne published The Lizard, a short story about an English gentleman who discovered and battled a carnivorous dinosaur in a cave near the English village of Kettlewell. The following year, American writer Wardon Allan Curtis’s science fiction short story, The Monster of Lake LaMetrie, was published in the September issue of Pearson’s Magazine; Curtis’ piece is written as the lost diary of a physician who discovered a living plesiosaur in a mountain lake in Wyoming, into the skull of which he transplanted the brain of his dying teenage companion. And in 1912, British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published his science fiction novel The Lost World, in which an ambitious young reporter accompanies an indomitable professor on an expedition to a remote stretch of South American jungle which supports a robust population of pterodactyls.

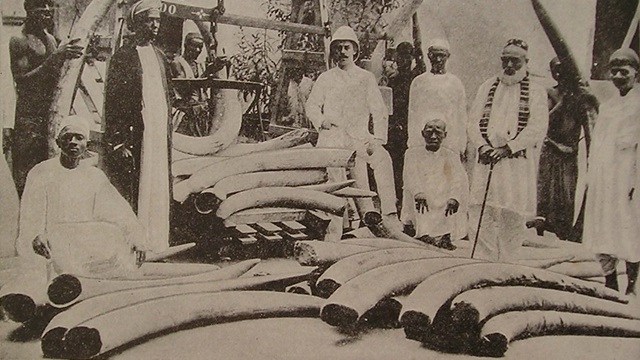

The Ivory Trade

While dinosaur mania took Victorian culture by storm, a contemporaneous but unrelated furor gripped the Western mercantile world. As a consequence of the Industrial Revolution and the political upheavals that characterized the Age of Revolution, a wealthy upper middle class composed of industrialists, doctors, lawyers, bankers, military officers, and other white collar professionals grew throughout the 19th Century. Many members of this burgeoning social strata flaunted their new wealth and standing by furnishing their drawing rooms with pianos, or ‘pianofortes’, as they were known at the time- luxuries which were once affordable only to the aristocracy. It became fashionable for middle class women and girls to study piano performance, an avocation redolent of high status and good breeding, and soon pianos were also making their way into the bedrooms of middle class ladies throughout the Western world. The fifty-two white keys adorning every piano in the Victorian era were covered with veneers of ivory, and in order to supply that ivory, a brisk trade in elephant tusks flourished in West and East Africa.

Mammoths in the North

The rising demand for ivory was concurrent with a decreased demand for fur, as men throughout the Western world began to prefer silk top hats to the beaver felt headgear affected by their fathers and grandfathers. Some far-sighted fur traders throughout Northern Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, eager to adapt to the changes affecting the Victorian market, began to purchase the tusks of woolly mammoths from the natives who had once brought them furs, those ancient ivory appendages being surprisingly common in the North Country, ensconced in the ever-eroding clay of riverbanks across the subarctic.

Throughout the course of their boreal wanderings, many of the ivory prospectors who hunted for these antediluvian relics came across partially-preserved mammoth carcasses mummified by the permafrost. In 1806, for example, zoologist M.F. Adams of the Russian Academy of Sciences learned that the body of a frozen mammoth had been discovered by Yakutian hunters on the banks of the Lena River in Siberia, with one eye still in its socket and its brain still in its skull. Despite that much of the mammoth’s flesh was subsequently devoured by wild wolves and hungry Yakutian sled dogs, Adams managed to secure a portion of the animal’s hide, which was so heavy that ten strong men were needed to drag it to their boat on the riverbank. In 1848, a Russian Orthodox missionary named Khitrovo allegedly discovered the frozen body of a mammoth on the banks of the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia, with food still in its stomach and twigs still in its mouth. And in 1898, a prospector named Angus Graham reputedly came across the remains of mammoth encased in ice somewhere in Yukon Territory, which disintegrated when it was exposed to the air.

In the late 1800s, prospectors, fur traders, and ivory hunters began returning from the wilderness of Northern Canada and Alaska with tales of living mammoths. In the May 5th, 1889 issue of the Philadelphia Press, for example, a fur trader named Cola F. Fowler described his 1887 purchase of what appeared to be a fresh mammoth tusk from a native chief. When questioned, the chief informed him that he and his band had encountered a small mammoth herd north of Nome, Alaska, and that some of his hunters killed an old bull and a cow with their large-caliber muskets. The March 4th, 1893 issue of the Sitka-based newspaper the Alaskan contained an article describing a Tahltan hunter’s recent brush with a woolly mammoth in the valley of the Stikine River in northwest British Columbia. And an article in the October 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine told a fantastic tale, which was later proven to be a hoax, regarding a successful mammoth hunt in the early 1890s in the Alaskan wilderness.

Georges Dupuy

On April 15th, 1908, an incredible article entitled “Le Monstre de Partridge Creek,” or “The Monster of Partridge Creek,” appeared in the French popular science magazine Je Sais Tout. Later that year, an English translation of the same piece appeared in the July-December 1908 edition of The Strand Magazine, a British publication which printed both factual articles and fictional stories. As a literary phenomenon, “The Monster of Partridge Creek” was the perfect marriage of the two different genres of literature above described, namely fictional tales of living dinosaurs and ostensibly-nonfictional accounts of prehistoric monsters in the North Country. Specifically, the piece describes an alleged encounter with a dinosaur in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

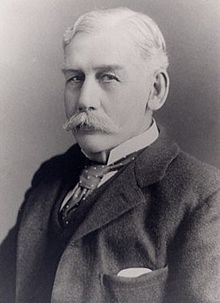

“The Monster of Partridge Creek” was written by a Frenchman named Georges Dupuy, whom Wikipedia identifies as 50-year-old Dr. Georges Marie Dupuy (1858-1935), a hard-headed Parisian physician and anatomical illustrator respected in the medical community for his contributions to the field of combat surgery. In fact, the author of the piece was almost certainly the doctor’s contemporaneous namesake and fellow Parisian, a 34-year-old journalist, writer, and translator who regularly contributed to the French sporting magazine l’Auto. In addition to writing articles on boxers, sprinters, and other athletes for the aforementioned publication, Georges Dupuy wrote at least one other short story for Je Sais Tout, which is set in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

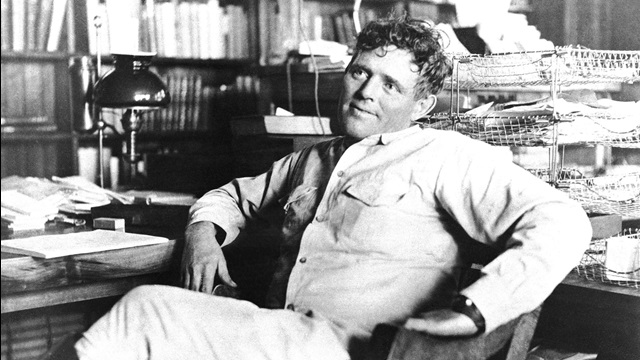

Dupuy was a Stampeder who had participated in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897. In a saloon in Dawson City, the heart of Klondike Country, he became acquainted with fellow writer Jack London, future author of the American literary classics White Fang and the Call of the Wild. Like London, Dupuy spent much of his time in Dawson plying old sourdoughs for tales of their backcountry adventures.

Dupuy made several trips from Paris to Yukon and Alaska in the decade following his prospecting days. On one such foray, which he undertook as a correspondent for l’Auto, he travelled to Nome, Alaska, to report on the condition of the Bering Strait sea ice, over which some quixotic industrialists hoped to build a highway- the most difficult stretch of a hypothetical thoroughfare connecting New York City with Moscow. “Just before twilight,” he reported, “some two miles or less distant, we could see the little blue waves out there in Bering Sea. Not once did it freeze more than five miles out, at Nome. But there are periods when the strait freezes.”

In 1904, Jack London hired Dupuy to translate his short story anthology The Faith of Men and Other Stories into French. In a letter to his friend and publisher, George Platt Brett Sr., in which he attempted to convince Brett that Dupuy was the man for the job, London wrote, “Mr. Georges Dupuy is a Frenchman, an artist, a journalist, & a man who knows Alaska better than I do. He has lived the life… I called him an artist, & by the word I mean not ‘painter’ but ‘temperament’. He sees. From my talks with him, I see that he has the romance, the fire, the color, the idiom of the land.”

The Monster of Partridge Creek

Despite London’s praise for the keenness of his mind’s eye, Dupuy was quick to assure his readers that the events described in “The Monster of Partridge Creek” were witnessed by the physical eyes in his head. “The story which follows is in no sense a romance,” he began. “I wish, in the first place, to ask the readers of the following narrative to believe that I am in no way attempting to impose upon their credulity. Concerning the amazing spectacle I am about to describe, I report nothing but plain facts, however astounding and apparently incredible they may seem at first glance, precisely as they appeared to my own eyes…”

Dupuy went on to explain how, in the early 1900s, one of his favourite Yukon haunts was a place called McQuesten Post. Although a trading post of that name once existed at the confluence of the Stewart and Yukon Rivers, Dupuy hints in his story that the McQuesten Post to which he referred was the North-West Mounted Police station which lay on the southern shores of the Stewart River opposite the mouth of the McQuesten River, about 75 kilometres (47 miles) west of the town of Mayo and 106 kilometres (66 miles) southeast of Dawson. Dupuy’s friend, a French-Canadian Jesuit missionary named Father Pierre Lavagneux, who tended to the spiritual needs of a nearby band of “Klayakuk Indians,” owned a cabin at McQuesten Post, which Dupuy visited every time he was in the area.

One morning in the early 1900s, the story goes, Dupuy was enjoying a cup of coffee on the veranda of Father Lavagneux’s cabin when he heard a whistle from the direction of the Stewart River. The Frenchman glanced up from his mug and was delighted to see his friend, James Lewis Buttler, kneeling in a bark canoe with an Indian at his fore and rear. The three men paddled over to the shore.

Buttler was a San Francisco banker who had left California in 1897 to try his luck in the Klondike. Dupuy knew that Buttler had spent the past few months prospecting in the wild country north of the Stewart River and was eager to learn whether he had met with any success.

Buttler’s greatest discovery, Dupuy soon learned, had nothing to do with gold dust or nuggets. Just two days earlier, the banker had been making his way overland towards the Stewart River when he came upon a cabin belonging to a man named Grant, who invited him to stay the night. The following morning, Grant asked Buttler if he would like to accompany him and two companions on a moose hunt. Buttler agreed, and the four men headed to Partridge Creek, a tributary of the Stewart which empties into the latter about six kilometres downstream from the mouth of the McQuesten River.

The hunters made their way up a hill overlooking a mineral lick off Partridge Creek where moose and caribou often came to taste the salt. Sure enough, they spied three enormous moose grazing in the valley below. Before any of the hunters could get off a shot, one of the animals- a young bull- let out a sharp bellow and crashed into the southerly bush, followed closely by his mates.

“We decided to approach the spot where the animals had taken fright so suddenly,” Buttler told Dupuy. “Arriving at the ‘moose-lick,’ a spot about sixty feet long and fifteen wide, we saw in the mud, and almost on a level with the water of the ‘lick’, the fresh imprint of the body of a monstrous animal. Its belly had made an impression in the slime more than two feet deep, thirty feet long, and twelve feet wide. Four gigantic paws, also deeply impressed, had left at each end of the main imprint, and a little to the side, footprints five feet long by two and a half feet wide, the claws being more than a foot long, the sharp points of which had buried themselves deeply in the mud. There was also the print, apparently, of a heavy tail, ten feet long and sixteen inches wide at the point.”

In the French-language version of the story, Buttler claimed that he and his companions found an enormous pile of strange greenish manure, which was clearly produced by some massive carnivorous animal, lying in the middle of the trail. This ominous excrement terrified the Indians.

Buttler and his companions followed the mysterious tracks for about five or six miles along the wooded banks of Partridge Creek until the coulee sharpened into a steep gulch. There, the tracks abruptly ended “as if by enchantment”.

At the conclusion of Buttler’s incredible tale, Dupuy suggested that the two of them assemble a hunting party and locate the mysterious creature that had made the tracks. By evening, Father Pierre Lavagneux; a local miner named Tom Leemore, who was working a claim on the McQuesten River; and five Klayakuk Indians agreed to accompany Buttler and Dupuy on their excursion. The Mountie who manned McQuesten Post and a courier who was staying in the area, both of whom were skeptical of Buttler’s story, decided to remain behind with Buttler’s two Indian guides.

Early the following morning, at about 5:00, the nine hunters paddled across the Stewart River in canoes and headed into the forest. They searched for signs of their mysterious quarry all day, slogging through brush and muskeg as they explored both Partridge Creek and the easterly McQuesten River, making their way north towards their headwaters in a nameless range of snowcapped mountains, but to no avail; the elusive creature was nowhere to be seen.

That evening, the nine companions set up camp at the crest of a cliff overlooking Partridge Creek and got a fire going. As they were boiling a pot of tea, the sound of falling stones could be heard in the ravine below. Before any of the men could investigate the commotion, a primeval roar ripped through the valley.

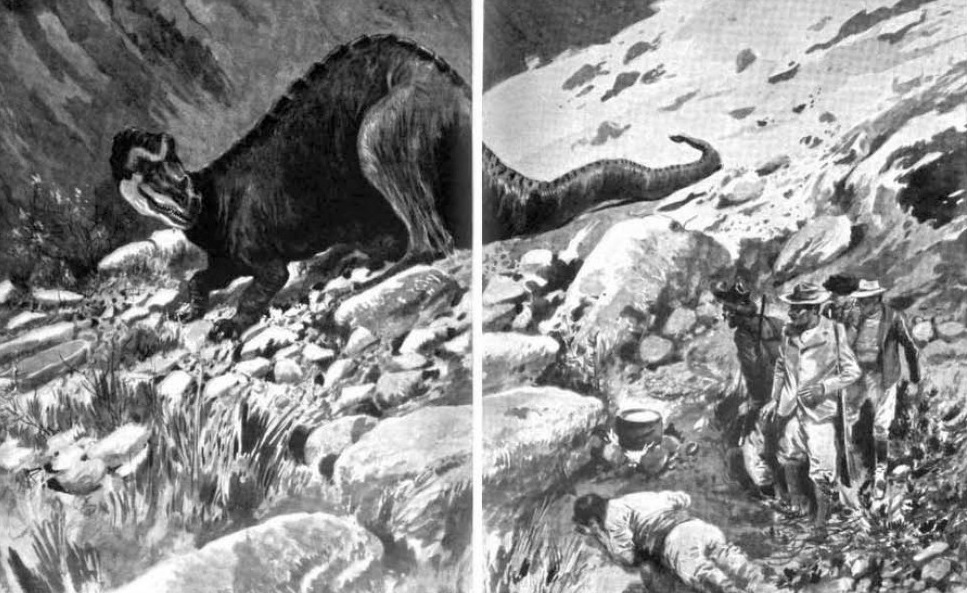

Gripping their rifles with trembling hands, Dupuy and his companions crawled over to the edge of the cliff and peered into the ravine. Across the narrow valley, on the other side of Partridge Creek, an enormous greyish-black creature was attempting to ascend the opposite slope. As it struggled to gain purchase on the rocky hillside with its clawed feet, it sent boulders crashing into the valley below.

Dupuy estimated that the monster measured fifty feet from its nose to the end of its tail, and that the crest of its spine stood eighteen feet above the ground. Its snout was “surmounted by a horn like that of a rhinoceros”, while its “hide was like that of a wild boar, garnished with thick bristles”. Red slaver dripped from its jaws; the monster had apparently just finished its dinner.

In the English version of the tale, Father Lavagneux declared that the creature must be a dinosaur. In the French version, the Jesuit, through chattering teeth, identified the monster as a Ceratosaurus, a dinosaur on which American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh had written extensively throughout the 1880s and ‘90s.

The hunters watched the strange animal for a full ten minutes, transfixed to the spot by both fear and fascination. “We were… in full possession of all our sense,” Dupuy wrote. “There was not, and never will be, in our minds the least doubt as to the reality of what we saw. It was indeed a living creature, and not an illusion, which we had before us.” Finally, when the creature recognized the futility of its exercise, it quit the slopes and bounded into the valley of Partridge Creek on two legs, moving with astonishing agility.

Following their terrifying encounter, Dupuy and Buttler made a trip to Dawson City, where they entreated the Commissioner of Yukon Territory for mules and fifty armed men with which to destroy the monster of Partridge Creek. “Here my story ends,” Dupuy wrote. “For a month we were the laughing stock of the Golden City, and the Dawson Daily Nugget published an article about me, which was at the same time flattering and satirical, entitled ‘A Rival of Poe’.”

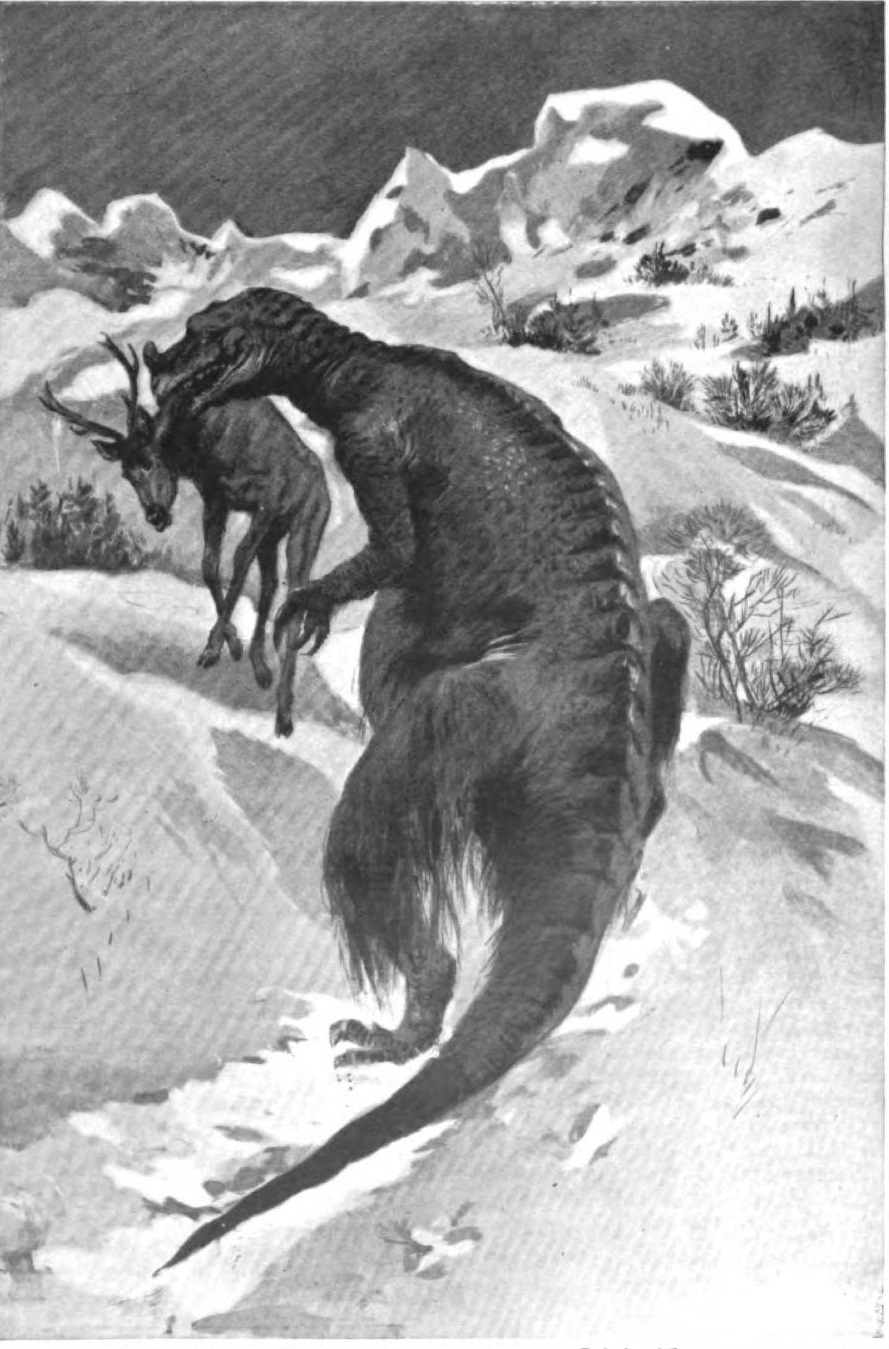

Near the beginning of his article, Georges Dupuy reproduced the contents of a letter that he claimed to have received from his friend, Father Lavagneux, which was written on New Year’s Day, 1908. After expressing his “affectionate wishes for [Dupuy’s] health and happiness,” and informing Dupuy of the death of John Spits, the mail carrier for the Duncan district northeast of Mayo, the priest disclosed that on Christmas Eve, just a week prior, he and ten members of his native congregation had seen the monster of Partridge Creek a second time, racing over the frozen surface of the creek with a caribou clamped between its jaws. “His fur was covered with hoar-frost,” he wrote, “and his little eyes gleamed like fire in the twilight.” The priest estimated that the animal ran at a speed exceeding ten miles an hour, and noted that the temperature at the time of the sighting was forty-five degrees below zero (-49o Fahrenheit).

Accompanied by a local Indian chief and two of his sons, Father Lavagneux followed the animal’s steadily-fading tracks two miles to the Stewart River, where the trail finally disappeared under a blanket of freshly-fallen snow.

A Hoax?

Many of those who have commented upon “The Monster of Partridge Creek” believe that it was intended as a work of fiction. In his 2017 article “A Brief History of Cowboys & Dinosaurs,” American comic book artist Stephen R. Bissette described the story as “one slice of great northern Yukon territory fiction- well, I’m convinced its fiction…- [which] has become enshrined as the real thing by certain cryptozoology circles”. American cryptozoologist Loren Coleman echoed Bissette’s statement in a May 27th, 2020 Twitter post, referring to the piece as “pure #cryptofiction set in Canada”.

Regardless of whether or not the story itself is true, “The Monster of Partridge Creek” was clearly presented as a non-fictional account of an actual dinosaur sighting in the Yukon. In The Strand Magazine, it is sandwiched between various non-fictional pieces, such as 34-year-old Winston Churchill’s account of his parliamentary service in Uganda, and a variety of obviously-fictional short stories, like a supernatural mystery by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle involving an overworked accountant and a haunted Scottish mirror. The magazine’s editor firmly placed Dupuy’s story in the non-fiction camp by giving it the headline: “Stories Strange and True”. Then, as if to dispel any remaining doubt as to its veracity, he added a short preamble- a direct translation of its French counterpart in Je Sais Tout– in which he declared that the story’s author is a “well-known French writer and traveler… whose good faith is beyond question, [and who] takes full responsibility for his narrative, which, it may be noted, however remarkable, in no way contradicted by known scientific facts.”

Subsequent to its debut in The Strand Magazine and Je Sais Tout, “The Monster of Partridge Creek” was republished in newspapers throughout North America. The verbiage of these reprints often deviated slightly from the original, undergoing a kind of subtle rewording to which non-fictional news articles are often subjected, but to which fictional pieces are invariably immune. Some articles declared that Tom Leemore had taken three photographs of the creature during the encounter which Dupuy described.

Galvanized by the sensational articles, 29-year-old Hugh Grosvenor, the wealthy Duke of Westminster, reportedly planned a hunting trip in Yukon Territory for the express purpose of bagging the monster of Partridge Creek. In preparation for his upcoming adventure, the Duke allegedly chartered a German steamer at Hamburg and fitted it with a huge steel cage in which the beast was to be contained. His plans were ultimately foiled in 1914, when the Great War broke out in the Old World. The Duke volunteered for combat duty and served with distinction in a prototypical armored car squadron on the frontlines in Egypt. By the time the war was over, he had apparently forgotten about his intended Yukon expedition, or had a change of heart or circumstance, and never rescheduled his trip to Stewart River Country.

Although “The Monster of Partridge Creek” was certainly presented, and initially received by many, as a true story, its context in literary history suggests that it was very possibly fictional in nature. Despite that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Lost World had not yet been published at the time the story was penned, inspiration for a tale of prehistoric survivors was in ample supply in 1908. Verne, De Mille, Hyne, and Curtis had already introduced living dinosaur fiction to the reading public, and American newspapers abounded with tales of mammoths and mastodons that roamed the frozen wastes of the subarctic. Perhaps most tellingly, Jack London’s anthology The Faith of Men, which Dupuy translated into French in 1904, included a tale entitled “A Relic of the Pliocene”. In this short story, the narrator encounters a lonely frontiersman deep in the subarctic bush, who tells him a campfire story about a live woolly mammoth- perhaps the last of its kind on earth- which he encountered in a remote valley in what is presumably the Mackenzie Mountains of Canada’s Northwest Territories. When the monster broke his gun and killed his dog, the frontiersman made it his mission to slaughter it. He accomplished this feat through persistence hunting, and celebrated his victory by crafting a pair of mukluks from the mammoth’s hide.

If “The Monster of Partridge Creek” indeed constitutes a piece of Northwestern fiction, it was not Georges Dupuy’s first foray into the genre. Two years earlier, he wrote a French-language story entitled Un Drame au Klondike, or “A Drama in the Klondike”, which was published in the February 15th 1906 issue of Je Sais Tout. This story tells of a French-Canadian prospector who murdered two of his fellow countrymen in the subarctic for their gold, only to be driven away from his prize by his victims’ vengeful sled dogs.

Its context in literary history is not the only indication that “The Monster of Partridge Creek” might be a fictional creation. In the very first paragraph, Dupuy refers to the Indians of the Stewart River as members of the Klayakuk tribe. In his French-language version, he implies that the Klayakuks comprise a band of “Snow Indians,” the “Snow Indians” perhaps being a general denotation for the Dene. In fact, the natives of Stewart River country are members of the Northern Tutchone First Nation, no bands of which go by a name bearing any resemblance to the word “Klayakuk”. The Koyukuk Indians, on the other hand, whose name the word “Klayakuk” strongly evokes, are members of a subdivision of the Koyukon Nation, whose historical homeland lies in central Alaska far from the Stewart River. Dupuy’s inclusion of the “Klayakuk Indians” in his narrative, considering his intimate familiarity with the North Country, almost seems to be a subtle wink to his Sourdough friends, to whom such an error, unnoticed by the vast majority of readers, might seem glaringly obvious. Dupuy’s friend, Jack London, inserted a similar inside joke into his novel, The Call of the Wild, with his inclusion of the murderous and completely fictitious Yeehat Indians.

Similar to the Klayakuk Indians, this author has failed to find any references to Father Pierre Lavagneux, James Lewis Buttler, and Tom Leemore in any books, academic articles, newspapers, or online posts aside from those related to Dupuy’s story.

Can Dinosaurs Survive in the Arctic?

In a commentary on “The Monster of Partridge Creek”, published in the September 1908 issue the Knowledge & Illustrated Scientific News, English naturalist Richard Lydekker wrote, “That a living representative of the carnivorous dinosaurs of the Secondary Epoch should be living in the frozen North of Alaska seems incredible to every scientific mind… The prima facie presumption is that the larger dinosaurs were inhabitants of warm rather than of Arctic zones.” British cryptozoologist Karl Shuker, who was perhaps the first in his field to critique the story, expressed a similar opinion in his 1995 book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors, writing, “The Monster of Partridge Creek… merits a prominent place among the dubitanda of cryptozoology… Bearing in mind… that the existence of such an animal calls for our belief in the post-Cretaceous persistence of an endothermic hairy dinosaur in what must surely be the last compatible habitat for any type of large reptile living today, its lack of cryptozoological credibility should hardly come as a great surprise!”

Conversely, British journalist and Fortean writer Harold T. Wilkins, in his 1952 book Secret Cities of Old South America, argued that Dupuy’s story, and the concept of relict arctic dinosaurs in general, might not be as farfetched as most readers might reflexively assume. “Paleontologists,” he wrote, “tell us that one of the principal reasons for the disappearance of dinosaurs and the monstrous reptilian of the great swamps and warm mosses of the hot Mesozoic Age- life’s long summer on the earth- was the oncoming of the Ice Age. After recurring periods of cold and less warmth, they say, the monsters died out, leaving no descendants. Yes, doubtless that was so; but who may say whether or not a peculiar type of dinosaur, existing in the Mesozoic Age, was able to adapt himself to changing climates and survive?” Indeed, since the 1980s, paleontologists have discovered dinosaur fossils in both the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, indicating that some dinosaurs were able to survive in colder temperatures than previously believed. “The finds are coming fast and furious,” wrote science writer Riley Black in a December 3rd, 2020 article for the Smithsonian Magazine. “A tiny jaw found in Alaska’s ancient rock record, and written about in July, indicates that dinosaurs nested in these places and stayed year round… The ongoing identification of new species, not found anywhere else, highlighted how some dinosaurs adapted to the cold.” Similar to their modern avian counterparts, paleontologists hypothesize that these creatures acclimated to lower temperatures by growing fuzz or downy feathers, going into torpor in underground burrows, or annually migrating to warmer climes in autumn.

Dinosaur Tail-Dragging

One potential hole in Dupuy’s story is the imprint that the monster’s tail purportedly left in the mineral lick, as described by James Buttler. Some writers have interpreted this detail as an indication that the dinosaur dragged its tail when it walked. This interpretation is probably incorrect, considering that the tail mark is only mentioned in connection with the single massive imprint of what was suspected to be the dinosaur’s belly, which the creature presumably made while wading through the soft, deep mud of the mineral lick; if the mud reached the creature’s belly, then it doubtless would have reached its tail as well, whether it was dragging or not. Whatever the case, the notion of a tail-dragging dinosaur accords perfectly with the mainstream Victorian and Edwardian perception of dinosaur biomechanics, which held that dinosaurs dragged their tails on the ground when they walked. In the 1970s, however, during a paleontological paradigm shift known as the “dinosaur renaissance”, American paleontologist Robert T. Bakker proposed that theropods like the Ceratosaurus were active creatures which used their tails to balance themselves when they ran. The paleontological community generally concurred with Bakker’s revolutionary theory, and today, nearly every interpretation of bipedal dinosaurs, from museum skeletons to movie monsters, depicts these ancient creatures with their tails in the air. In recent years, theories on dinosaur locomotion have begun to come full circle with the discovery of what have been interpreted as dinosaur tail-drag marks- clear indications that some dinosaurs did indeed drag their tails when they walked, as Victorian scientists initially suspected.

Dinosaurs in Siberia

In 1922, newspapers across North America reported that a family of carnivorous dinosaurs resembling Ceratosauri had been spotted in the Soviet Union’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Indigenous hunters allegedly discovered the mangled remains of a young Ceratosaurus in Russia’s boreal wilderness, and brought one of its severed feet, which was the size of a man’s head, back to civilization. Some journalists who commented upon the story suggested that these alleged Russian dinosaurs might be kin to the monster of Partridge Creek, speculating that such creatures might cross the Bering Strait during especially severe winters, when Kamchatka and Chukotka were linked to Alaska by an unbroken stretch of ice. When a subsequent expedition in search of the Russian dinosaurs proved fruitless, some suggested that the prehistoric remnants abode within the Chersky Mountains, a range newly discovered in northeastern Siberia, between the Yana and Indigirka Rivers.

Chequina’s Story

Throughout the 1930s, Canadian writer and former Hudson’s Bay Company inspector Philip H. Godsell wrote a number of articles in which he included a story that had been told to him by his friend, Frank Beatton, the HBC’s Chief Factor at Fort St. John, British Columbia. Beatton had heard the story from a scientific party; whose members had heard it from one of their Indian guides, a Cree named Chequina; who had, in turn, heard the tale from his father. Sometime in the late 19th or early 20th Century, Chequina’s father had purportedly travelled to the Upper Liard River Country in what is now southeastern Yukon, where he fell in with a primitive tribe of Dene Indians. “Around their fires,” Godsell wrote, “these Stone Age people had told of a ‘medicine valley’ to the north, inhabited by monsters of fearful size and ferocity.” One of the Cree’s new Dene acquaintances produced a scrap of buckskin from his medicine bag, on which had been burned the image of one of these monsters. The Cree treasured this charm for years, and eventually bequeathed it to his son, Chequina, who, in turn, later showed it to the scientific party he was tasked with guiding. The scientists told an incredulous Beatton that the figure depicted on the buckskin scrap was a ‘dinosaur’, drawn in flawless anatomical detail.

The world will never know what Georges Dupuy’s opinions might have been on the alleged Ceratosauri of Siberia, the story of Chequina’s buckskin drawing, and the controversy that his own tale engendered; the journalist died prematurely in 1911, just three years after the publication of his most contentious article, bringing the secret of Partridge Creek with him to the grave. Paleontologists, cryptozoologists, and literary historians can speculate all they like as to whether his tale has any truth at its core, but until definite answers in some long-forgotten letter or long-lost journal are discovered and brought to public awareness, the monster of Partridge Creek will remain one of the great unsolved mysteries of Canada.

Sources

Le Monstre de Partridge Creek, by Georges Dupuy in the February 15, 1908 issue of Je Sais Tout

The Monster of Partridge Creek, by Georges Dupuy in the July 1908 issue of The Strand Magazine

The World’s First Dinosaur Park: What the Victorians Got Right and Wrong, by Emily Osterloff on the website of London’s Natural History Museum

The Rise of the Middle Classes: A Victorian Phenomenon, by Val McBeath on ValMcBeath.com

Dinomania: The Story of Our Obsession with Dinosaurs, by Tom Holland in the June 5th, 2015 issue of The Guardian

Who Wrote the First Dinosaur Novel, by Riley Black in the December 8, 2011 issue of Smithsonian Magazine

The Carcasses of the Mammoth and Rhinoceros Found in the Frozen Ground of Siberia, by I.P. Tolmachoff in the 1929 journal of the American Philosophical Society

A Climatic Paradise Was the Earth in Early Days, by Professor Ezekiel Stone Wiggins in the Saturday, March 19, 1898 issue of the Evening Journal (Ottawa)

Strange Stories of Alaska and the Yukon (1996), by Ed Ferrell

“A Brief History of Cowboys & Dinosaurs,” by Stephen R. Bissette in Red Range: A Wild Western Adventure (2017)

English Nobleman on Hunt for Great Living Monster in Alaska, by “An American in Paris”, in the May 31st, 1908 issue of the Great Falls Daily Tribune

In Search of Prehistoric Survivors: Do Giant ‘Extinct’ Creatures Still Exist (1995), by Dr. Karl P.N. Shuker

“A Relic of the Pliocene” in The Faith of Men and Other Stories (1904), by Jack London

The Letters of Jack London: 1913-1916. Volume III (1988)

The Monster of Partridge Creek, by Richard Lydekker in the September 1908 issue of the Knowledge & Illustrated Scientific News

Secret Cities of Old South America (1952), by Harold T. Wilkins

How Dinosaurs Thrived in the Show, by Riley Black in the December 3rd, 2020 issue of the Smithsonian Magazine

Dinosaurs Rediscovered (2019), by Michael J. Benton

Tail-Drag Marks and Dinosaur Footprints from the Upper Cretaceous Toreva Formation, Northeastern Arizona, by Grace V. Irby and L. Barry Albright III in the 2002 issue of Palaios

Prehistoric Monster Still Haunts Arctic, by Sterling Heilig in the December 17th, 1922 issue of the New York Herald

Huge Monster of Arctic Seen, by Sterling Heilig in the January 20th, 1928 issue of the Chicago Tribune

Leave a Reply