Another Wrinkle in the Wilkins Map

Hello, and welcome to Another Wrinkle in the Wilkins Map. In this video, we’re going to reveal a new research-related discovery pertaining to one of the strangest chapters in the history of the Oak Island treasure hunt. To give this revelation some context, we’ll first dive into the tale of Captain Kidd, a notorious Scottish pirate whose legendary lost treasure, some believe, may lie at the bottom of the Money Pit. Next, we’ll explore the story of the Wilkins Chart- the tale of an eccentric British journalist and a mysterious treasure map with an unusual connection to the Oak Island mystery. Finally, we’ll draw back the curtain on a secret that has remained hidden for over sixty years. Without further ado, here is Another Wrinkle in the Wilkins Map. Enjoy!

If you’re into mysteries, buried treasure, or the History Channel, chances are that you’re familiar with Oak Island, Nova Scotia, the site of Canada’s longest treasure hunt. As of 2019, no one truly knows what lies buried beneath Oak Island, although many theories have been put forth purporting to explain the nature of the island’s elusive treasure and the identity of those who buried it.

When Daniel McGinnis, John Smith, and Anthony Vaughan first discovered Oak Island’s so-called ‘Money Pit’ in 1795, they initially suspected that they had stumbled upon a cache of long-forgotten pirate loot. From the 16th Century to the late 18th Century, Mahone Bay, in which Oak Island is located, had been a frequent haunt of pirates, and as a result, local yarns of lost pirate plunder abounded. One particular legend favoured by the early settlers of nearby Chester, Nova Scotia, was that surrounding Captain William Kidd- a 17th Century Scottish privateer who, prior to his execution for piracy in 1701, is said to have buried a fabulous treasure on some undisclosed island. Following the discovery of the Money Pit, many locals believed Oak Island to be the repository of Captain Kidd’s legendary treasure.

The Tale of Captain Kidd

The tale of Captain Kidd begins in 1688- a momentous year in English history. The British throne was occupied by King James the Second, a Catholic monarch. At that time, most of England- and, more importantly, most members of the English Parliament- were Protestant, and many of them had little love for their Catholic king. Determined to put a fellow Protestant on the British throne, a cabal of Parliamentarians secretly plotted with King James’ nephew and son-in-law, Prince William III of the Netherlands. Their scheme resulted in a successful coup d’etat in which Prince William, with a fleet of 600 ships and 40,000 mercenaries, sailed through the Strait of Dover and across the English Channel. The Dutch prince and his soldiers disembarked at Torbay, marched on London, and seized the throne from King James in what the Parliamentarians dubbed the “Glorious Revolution”.

Although the deposed King James had been on friendly terms with Louis XIV, the powerful King of France, the Dutch prince-turned-King of England was an old and bitter enemy of the French monarch. Immediately after his coronation, King William the Third thrust Britain into the ongoing Nine Years’ War, a conflict between France and much of continental Europe.

At that time, a mysterious 35-year-old Scottish sailor named William Kidd was at sea in the Caribbean, serving aboard a French privateering ship called the Sainte Rose. Since France was now at war with England, the ship’s captain was given a letter of marque to capture English vessels.

Naturally, Kidd and seven other patriotic British crewmembers were loath to attack fellow Englishman. Under the leadership of Kidd and a Cornish privateer named Robert Culliford, the Britons mutinied against the Sainte Rose’s French crew, renamed the ship the Blessed William, and nominated Kidd their new captain.

Captain Kidd and his crew sailed the Blessed William into Nevis, a small English island colony about 190 nautical miles southeast of Puerto Rico, where the governor of the colony welcomed them into his own small fleet. Although the governor could not afford to pay Kidd and his crew, he allowed them to take whatever plunder might be had from any French ships and settlements they came across. And thus William Kidd became a respectable English privateer.

After a year of defending the island of Nevis from the French navy- an occupation which offered little in the way of treasure- Kidd’s old friend and fellow mutineer, Robert Culliford, decided that he’d had his fill of privateering. While Kidd was ashore the island of Antigua, Culliford and the rest of the crew, tired of the strictures of licensed privateering, left the docks and sailed into the Caribbean to pursue the pirate life. Relieved of his command, Kidd boarded a ship to New York, where he promptly married a wealthy English widow and became one of the richest men in town.

Despite being an active and upstanding member of the little colony, Kidd quickly tired of domestic life and returned to sea. For four years, he worked as a merchant captain, shipping goods to and from New England and the Caribbean, and earning himself a good reputation in the process. His new occupation did little to satisfy his appetite for adventure, and so in December 1695, William Kidd sailed for London, England, where he hoped to apply for a captain’s commission in the British Royal Navy.

By pure chance, Kidd bumped into a fellow New Yorker on the streets of London- a wealthy businessman named Robert Livingston. When Kidd told Livingston of his ambition, the businessman introduced him to his Irish friend Richard Coote, the Earl of Bellomont, who also happened to be the newly-appointed Governor of New York. The two men asked Kidd if he would consider accepting a commission to lead a pirate-hunting expedition along the so-called Pirate Round, a sailing route that led across the Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Hope, past Madagascar, to the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea beyond. There, pirates plundered Indian passenger ships filled with exotic goods and wealthy Mecca-bound pilgrims, as well as the British East India Company’s merchant vessels which often accompanied them- predations which strained England’s valuable relationship with India’s Mughal Empire.

For William Kidd, the offer seemed the opportunity of a lifetime. He accepted the invitation and secured financial backing from Livingston, Coote, and four powerful English aristocrats who insisted upon the condition that they receive three quarters of any treasure that Kidd and his crew managed to acquire. Finally, King William the Third himself gave Captain Kidd a letter of marque reserving 10% of the loot for the British Crown, and giving Kidd royal license to capture or sink pirate ships or French vessels he came across.

Equipped with a brand new 34-cannon oared frigate called the Adventure Galley and accompanied by a hand-picked crew, Captain Kidd sailed down the River Thames. On the way to the sea, his men disrespected the crew of a yacht of the Royal Navy. As punishment for the offence, the yacht’s captain pressed most of Kidd’s sailors into naval service, leaving the Scottish captain with a barely functional skeleton crew.

Short-handed, Kidd sailed across the Atlantic to the port of New York, where he supplemented his meagre crew with a large number of hardened pirates. In order to convince these rough sailors to sign aboard his ship, Kidd agreed to give them 75% of whatever plunder they might acquire as opposed to the 25% stipulated by his license. In doing so, Kidd violated his letter of marque- a misdemeanor which would contribute to his eventual undoing.

His ranks filled, Captain Kidd set out on the Pirate Round, determined to abide by the conditions of his license. Rather than French or pirate vessels, however, Kidd and his crew met only with misfortune. On December 11, the Adventure Galley was approached by a convoy of British Royal Navy men-of-war. The flotilla’s commander, Commodore Thomas Warren, ordered Kidd to accompany him to the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, hoping to impress some of his sailors into service in his own fleet.

Rather than deliver members of his own hard-won crew to Commodore Warren, Captain Kidd decided to slip away in the night and continue on alone. This evasion led Warren to believe that Kidd and his crew had something to hide, prompting him to spread the rumour throughout the British East India Company that privateer Captain Kidd had gone rogue.

The crew of the Adventure Galley rounded the southern tip of Africa and sailed along the coast of Madagascar. When they failed to encounter any enemy ships in that notorious pirate haven, they sailed northwest to the Comoro Islands to patch up their ship. There, two thirds of the crew came down with dysentery. Forty of them died within a week.

When the disease ran its course and the survivors had regained sufficient strength to continue their voyage, the crew of the Adventure Galley headed north to hunt for pirates and Frenchmen. In late June, they arrived at the mouth of the Red Sea and lay at anchor, ready to pounce on any enemy ships that approached. By this time, Captain Kidd’s crew was growing restless, and whispers of mutiny rippled throughout the decks.

Although the crew of the Adventure Galley never encountered any pirates in the Arabian Sea, they were fired on by English, Dutch, Portuguese, and Arabian ships whose captains thought they were pirates themselves.

Weeks turned into months, and by the fall of 1697, Kidd’s crew was on the brink of mutiny. On October 30, 1697, one of the crewmembers- a gunner named William Moore- sat on deck sharpening a chisel and muttering under his breath. When Kidd inquired as to Moore’s rumblings, the gunner urged Kidd to attack a nearby Dutch ship and plunder its cargo- a flagrant act of piracy. When Kidd refused, a quarrel ensued which ended with Kidd cracking Moore over the head with an iron-ringed bucket. The blow fractured Moore’s skull, and the gunner succumbed to his wound the following day.

Not long after Moore’s death, Kidd and his crew, through the practice of flying false colours, managed to capture a French ship without a shot being fired- a capture in accordance with Kidd’s commission. The crew of the Adventure Galley appropriated two chests of opium, twelve bales of cotton, and other odds and ends from the French vessel before continuing down the Malabar Coast of southwestern India.

On January 30, 1698, the Scottish captain, using similar tactics, captured the massive Quedagh Merchant, an Indian merchant vessel loaded with silk, satin, gold, silver, jewels, and a variety of valuable East Indian goods. Kidd learned that the ship was chartered by the French East India Company and owned by a company of Armenian merchants, and was initially satisfied that this capture was a legitimate one. However, upon further investigation, he learned that the ship’s captain was English, and that the vessel was part of the same Muslim fleet whose piratical predators he was tasked with combatting. Worse, a large proportion of the ship’s cargo was owned by a senior official of the Mughal Empire. Kidd tried to convince his crew to return the ship’s cargo, but the disgruntled sailors would have none of it. Unwilling to risk a mutiny, Kidd reluctantly acceded to their demands and set sail for New York. His capture of the Quedagh Merchant branded him a pirate, and his notorious reputation quickly preceded him throughout the Atlantic.

With the two freshly-captured merchant ships trailing behind them, Captain Kidd and his crew sailed across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar. Before heading home, the Scottish captain decided to pay a visit to Ile Sainte-Marie, an infamous pirate haunt off Madagascar’s eastern coast. Sure enough, he found a pirate ship bobbing in the harbor- the first of its kind that he and his crew had encountering throughout their entire grueling voyage. Kidd soon learned that the frigate was captained by none other than Robert Culliford, the pirate who had mutinied against him in the Caribbean.

Hungry for revenge, the privateer donned his cutlass, loaded a brace of flintlock pistols, and asked his crew to help him take the ship. Many of his sailors were former pirates themselves however, and had come to despise their strict Scottish captain. Rather than attack Culliford, the vast majority opted to throw in their lot with the Cornish buccaneer. They defected to the other ship, leaving Kidd with a mere fifteen loyal sailors. Having miraculously retained most of their precious cargo, Captain Kidd and his tiny crew abandoned the rotting Adventure Galley for the Quedagh Merchant and headed for home.

The privateers followed trade winds across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. There, they learned that the governor of every English colony had orders to arrest them for piracy. After bartering silks and other fabrics for provisions and a new ship, Captain Kidd followed the Gulf Stream north to New England.

Just outside the New York harbor, Kidd received word that one of his main backers, Richard Coote, the Governor of New York, had agreed to offer Kidd clemency for his piracy. In a letter, the Irish aristocrat invited Kidd to sail into Boston Harbour, where he was currently doing business. Captain Kidd decided to accept the invitation. Before heading to Boston, however, he cached a large part of his treasure on Gardiner’s Island, off the eastern shores of Long Island, New York, just in case he found himself in need of leverage.

Captain Kidd’s suspicions were well founded. Less than a week after arriving in Boston Harbour, he and his crew were arrested by the local police and imprisoned in the city jail. Richard Coote, one of his major backers, had betrayed him.

Over the following year, Kidd enduring a long imprisonment followed by a hugely unfair trial in which he was convicted of piracy and the murder of his gunner, William Moore. After the verdict was passed, Kidd sent a letter to the Speaker of the English House of Commons claiming that he had hidden a hoard of treasure valued at 100,000 pounds sterling- worth twenty million American dollars today- and that he would help find it for the Crown if he was spared the noose.

His entreaty fell on deaf ears. On May 23, 1701, at London’s Execution Dock, Captain William Kidd was hanged. His body was then suspended in a gibbet over the River Thames for three years as a warning to pirates.

Captain Kidd’s Treasure

Following Kidd’s execution, Englishmen throughout the Empire speculated as to the nature and whereabouts of the treasure the pirate captain claimed to have hidden. Could Kidd have invented the tale as a desperate attempt to delay his appointment with the gallows? Or was there truly a hoard of gold and silver hidden away on some lonely shore, just waiting to be discovered?

Legend has it that, half a century later, in the mid-1700s, an old sailor from New England lay dying. On his deathbed, he confessed to his family that he had been a member of Captain Kidd’s crew. Before passing away, he disclosed that he had helped the pirate captain bury his sizeable treasure on an island east of Boston.

Naturally, when Daniel McGinnis, John Smith, and Anthony Vaughan discovered a depression in the soil on Oak Island, with a block and tackle suspended from the oak tree that grew at its edge, they hoped that they had stumbled upon Kidd’s legendary loot. So did most of the other treasure hunters to try their luck on Oak Island throughout the 19th Century.

Wilkins’ Map

In 1934, the Oak Island treasure hunt was taken up by Gilbert Hedden, a retired steel manufacturer from New Jersey. His brief and exciting tenure on the island was marked by one of the most bizarre chapters in the history of Oak Island.

In 1937, Hedden’s lawyer, Reginald V. Harris, read a recently-published book written by British journalist Harold T. Wilkins entitled Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island. The first twelve chapters of this book describe the life of Captain Kidd and the aftermath of his execution. The next seven chapters detail various hunts for his supposed treasure. The final chapters of Wilkins’ book reveal a new break in the case: the discovery of four 17th Century treasure maps said to have once belonged to Captain Kidd.

These treasure maps, Wilkins claimed, were recently discovered by a wealthy Englishman named Hubert Palmer, who collected genuine pirate artifacts as a hobby. Throughout the 1930s, Palmer acquired four pieces of 17th Century furniture bearing engravings which indicated that they once belonged to William Kidd. Within each of these artifacts was a secret compartment, and within each compartment was a treasure map depicting a particular island in the South China Sea.

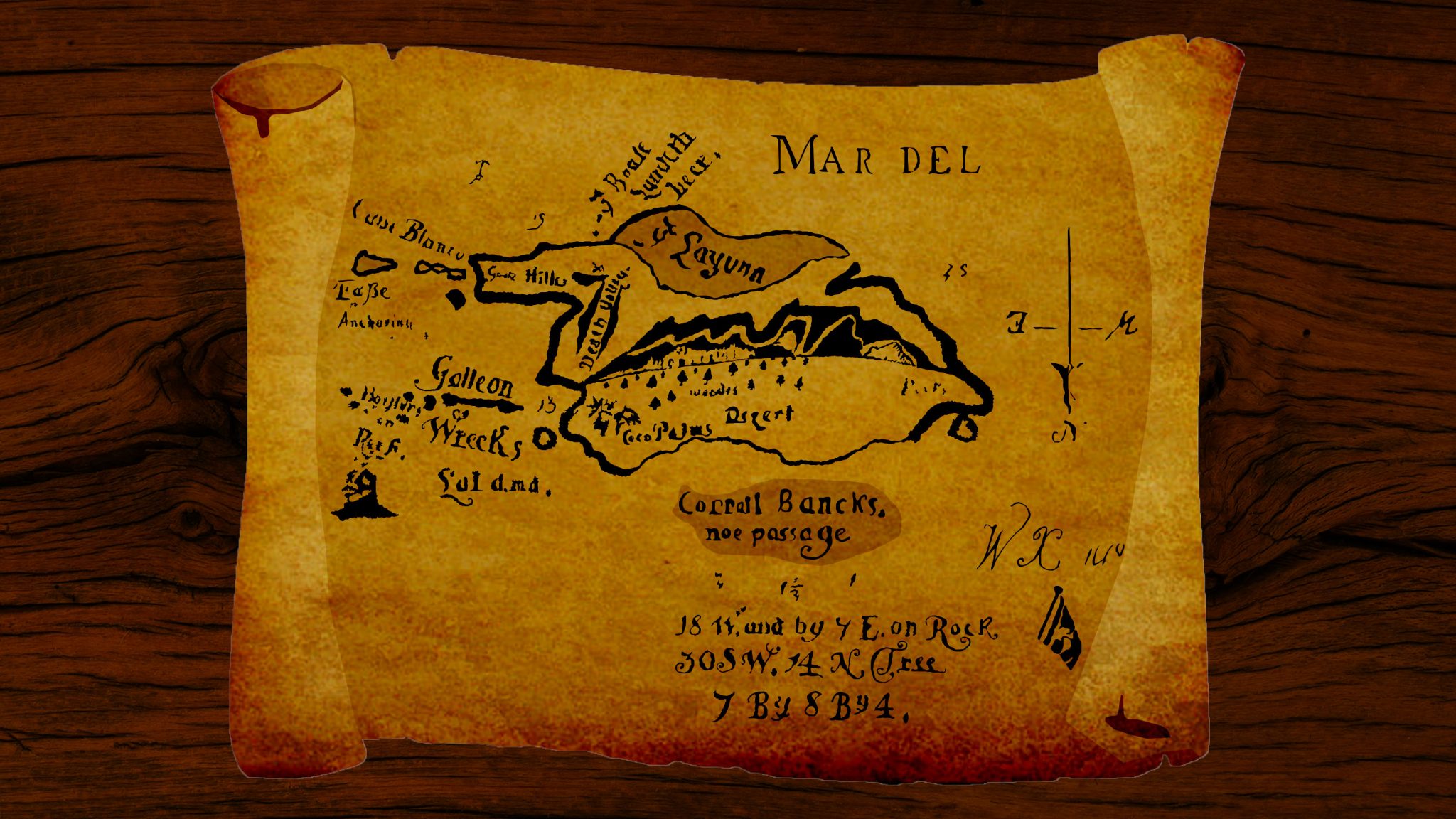

At the end of his book, Wilkins included a number of photographs featuring the four pieces of antique furniture, Kidd’s letter of marque, and various portraits of the notorious 17th Century pirate. Hidden among these photographs is an image of a hand-drawn treasure map with a reversed compass, which an accompanying description describes as the first chart that Palmer discovered in Captain Kidd’s supposed sea chest. The map included a cryptic legend which reads:

18 West and by 7 East on Rock

39 Southwest 14 North Tree

7 by 8 by 4

Reginald Harris couldn’t help but notice that this treasure map, when flipped right-side up, bore remarkable resemblance to Oak Island. Even more intriguing was the fact that many of the map’s features corresponded with landmarks on Oak Island. The lagoon, for example, was eerily congruent with Oak Island’s swamp; the elevations shown on the map were in the same locations as hills on Oak Island; and cross on the map matched the location of the Money Pit. In total, Harris identified fourteen resemblances between Wilkins’ map and Oak Island, and only one minor discrepancy.

Harris showed the map to Gilbert Hedden, who was similarly fascinated by its uncanny resemblance to Oak Island. Hedden became convinced that Wilkins’ chart might, in fact, be a real Oak Island treasure map drawn up by the original Money Pit builders, and so he sent a letter to Harold Wilkins voicing his suspicion.

Wilkins sent a letter back to Hedden assuring him that the treasure map in his book was not a map of Oak Island, but rather a depiction of an island in some ‘eastern sea’ far from the Atlantic. Hedden was unconvinced. To him, the similarities between Wilkins’ map and Oak Island were too strong to be coincidental. He then turned his attention towards the mysterious directions at the bottom of the chart.

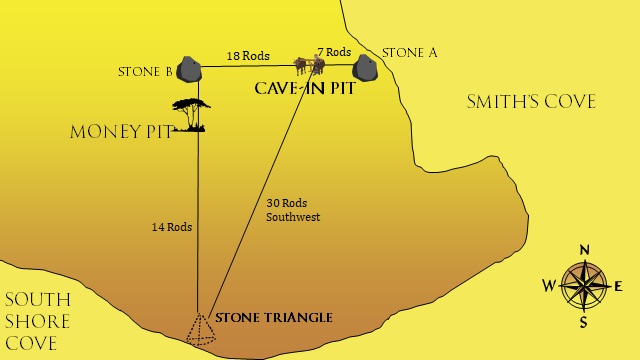

The first line of directions seemed to suggest that the first step in the treasure hunt was to locate some sort of prominent rock, probably situated on the beach somewhere near the spot at which treasure hunters would be most likely to disembark. In the case of Oak Island, that beach was probably Smith’s Cove, the section of the island most exposed to the ocean. While discussing this possibility with an elder treasure hunter named Frederick Blair, Hedden learned that two mysterious drilled rocks had been discovered on Oak Island long ago, and that one of these rocks lay on the shores of Smith’s Cove. Hedden had his crew search for these stones, and sure enough, a rock with a 2-inch-deep, 1-inch-in-diameter hole was discovered at Smith’s Cove. Another rock with a similar hole was subsequently found about fifty feet north of the Money Pit.

The rocks were found to be exactly 25 rods apart from one another, rods being an old English unit of measurement amounting to about five metres, or five and a half yards. Exactly seven rods west of the stone at Smith’s Cove, and eighteen rods east of the western stone, lay the Cave-in Pit, a mysterious depression believed by many to be the site of an airshaft dug by the builders of the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel. The Cave-in Pit appeared to be the place indicated by the first line of directions on Wilkins’ map.

After making that tantalizing discovery, Hedden focused on the second line of directions. First, he had one of his employees, named Amos Nauss, run a line thirty rods southwest of the Cave-in Pit. In Nauss’ words:

“Hedden gave me some idea that there was something down there at the beach that he wanted to find. So I explored around there with a hoe. I was clawing around and suddenly I hit one rock, then another and another, all in line with each other. So I decided there was something there, and I started clearing it and called Hedden over.”

Nauss had rediscovered the stone triangle, a mysterious arrangement of beach stones on the South Shore Cove forming an arrow which pointed due north, in the direction of the Money Pit.

Astonished, Hedden ran a line fourteen rods north of the stone triangle. Sure enough, the line ran to the edge of the Money Pit, where legend says a large oak tree once stood. The directions on Wilkins’ map seemed to apply perfectly to Oak Island.

Although he could make neither heads nor tails of the last line of directions, Hedden was convinced more than ever that the chart in Wilkins’ book was a genuine Oak Island treasure map. Determined to follow this new and exciting lead, he decided to travel to England and meet Harold Wilkins in person. When Hedden informed the writer of his intentions, Wilkins wrote back that he was willing to meet with the treasure hunter, but that such a journey would be a waste of time, as the map in his book was definitely not an Oak Island treasure map. Nevertheless, Hedden made the trip to England and met with Wilkins in December, 1937, in his London hotel room outside Green Park, Piccadilly. His experience was both strange and discouraging.

Upon meeting Hedden, the English author confessed that the map in his book was, in fact, a diagram of his own devising. His publisher had demanded that he include some sort of authentic-looking treasure map in his book. Hubert Palmer, the owner of the four Captain Kidd maps which Wilkins described in his book, would not allow him to publish photos of his charts, and so Wilkins had no choice but to draw his own treasure map based on his recollection of Palmer’s maps. When his publishers further stipulated that his map contain instructions on how to locate the treasure for added spice, Wilkins fabricated the three lines of directions using nothing more than his imagination.

Baffled by the remarkable connection between Wilkins’ ad-libbed treasure hunting instructions and the landmarks on Oak Island, Hedden told the journalist all about the mysterious drilled stones, the stone triangle, the Cave-in Pit, and the oak tree believed to have once stood beside the Money Pit, and the uncanny relationship between these landmarks and the instructions on Wilkins’ map. As Hedden explained the extraordinary coincidence, Wilkins became convinced that he must be the reincarnation of a 17th Century pirate, perhaps even Captain Kidd himself, and that his subconscious mind had conjured up some long-forgotten memory of the map leading to Kidd’s lost treasure, buried on Oak Island. After Wilkins enthusiastically revealed his conviction to Hedden, the latter began to suspect that the journalist was, in his words, “every bit as crazy as his book would make him seem.”

Bill Burrud’s Treasure Map

Although many Oak Island enthusiasts today are familiar with the mystifying saga of the Wilkins Map, very few are acquainted with its strange follow-up – a puzzling sequel which will be presented for the first time in this video.

In 1958, a former child actor and WWII veteran named Bill Burrud [BURR-rud] produced a TV series entitled Treasure. This series was essentially a collection of documentaries on buried loot, forgotten gold mines, and lost cities. One of the episodes, incidentally, is on the mystery of Oak Island.

Another episode of Treasure, entitled “Shipwreck of the Dry Tortugas [tor-TOO-guz]”, follows the hunt for a shipwreck located off deserted island located about 90 miles west of Key West, Florida, just beyond a cluster of islands called the Dry Tortugas. The episode opens with a shot of a large treasure map. The viewer may recognize this document as an augmented, coloured replica of the chart from Harold Wilkin’s book Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island.

In the first few minutes of the program, we are informed that the map was brought to the show’s producer by one of their viewers, a Mr. David Buckner of Key West, Florida, and that it had been in Buckner’s family for generations. The map allegedly shows the location of a French merchant ship which had wrecked off the island in 1883, stranding its valuable cargo on a coral reef.

After introducing us to the map, the show follows the journey of actors Gene McCabe and Lee Hanson, who set out in search of the shipwreck. First, the pair travel to Key West, where they meet with a tanned, rugged-looking skin diver named Ed Soszynski . The treasure hunters show Soszynski their treasure map and tell him the story of the French shipwreck. The skin diver claims to know the island, locating it on his own nautical charts, and agrees to take the treasure hunters to it. With that, the three men climb aboard Soszynski’s boat and head west.

On their way to the shipwreck, the treasure hunters pay a visit to Fort Jefferson, a huge American fortress built in 1825 for the purpose of suppressing piracy in the Caribbean. There, Soszynski tells the treasure hunters that, according to legend, the sole survivor of the French shipwreck had washed ashore at Fort Jefferson clinging to a piece of wreckage. The survivor informed the fort’s garrison that he and his crew were beset by a ferocious gale. Worse, they had been led aground a coral reef by mysterious signal lights which suddenly appeared at the height of the storm. No one knew where the lights came from.

On the advice of Fort Jefferson’s caretaker, the treasure hunters then proceed to Bleaker’s Island, named for a hermit named Vincent Bleaker who lived there in the late 1800s. According to the caretaker, rumour had it that Bleaker would stand in his beach shack during storms and hoist a lantern in the hope that some unfortunate ship would run into the coral reef that fronted his island, leaving its cargo for the taking. Perhaps, the narrator suggests, Bleaker had a hand in the demise of the French ship.

After exploring the deserted island, the trio head towards their final destination. True to his word, Soszynski leads the treasure hunters to a sunken ship entombed in coral. Donning scuba gear, the treasure hunters explore the ship and recover a few interesting artifacts, including a cannonball, an old hatch cover, a swivel gun, a piece of ivory, and some sterling silver tableware. Pleased with their discoveries, the treasure hunters head for Key West as the sun begins to set.

The shipwreck that Gene McCabe, Lee Hanson, and Ed Soszynski explored in this episode of Bill Burrud’s Treasure is undoubtedly real. The legitimacy of the treasure map which ostensibly prompted their treasure hunt, however, is another question entirely. Upon close inspection, the map appears to be artificially weathered, apparently for the purpose of making it older. The map, it seems, is probably a hoax intended for dramatic effect.

Somewhat more puzzling is the fact that the map appears to conform in shape with some unnamed island allegedly located off the Dry Tortugas, as evidenced by the nautical chart produced by Soszynski prior to the treasure hunt. Although the resemblance is probably coincidental, it adds yet another twist to the convoluted tale of the Wilkins Map and the most bizarre chapter in the history of the Oak Island treasure hunt.

Thanks for watching! If you enjoyed this video and would like to help support this channel, check out the Oak Island Encyclopedia, the unauthorized guide to The Curse of Oak Island, which you can find by clicking the link in the description.

Sources

- The Oak Island Mystery (1967), by R.V. Harris

- The Secret Treasure of Oak Island (2004), by D’Arcy O’Connor

- Captain Kidd and His Skeleton Island (1935), by Harold T. Wilkins

- “Mystery of the Pirate’s Chart” in the December 1950 issue of FATE; courtesy of American Fortean researcher Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- “Shipwreck of the Dry Tortuga” (1958), in Treasure, by Bill Burrud Productions; courtesy of Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- “On the Treasure Trail of the Wicked Old Pirates,” by Harold T. Wilkins in the February 18, 1940 issue of the San Francisco Examiner; courtesy of Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- Maps, Mystery, and Interpretation: 1,2,&3 (2013), by G.J. Bath

- Treasure and Intrigue: The Legacy of Captain Kidd (2002), by Graham Harris

- The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd (2002), by Richard Zacks

George Edmunds

Regarding the so called Kidd (Wilkins) treasure charts, most of the above is unnecessary waffle! The treasure DOES NOT EXIST! See ‘Anson’s Gold’ pub 2016 and you will see the real truth about these (Deceptive) charts. Wilkins knew all about a huge Spanish treasure that Lord Anson looked for, he cleverly hid clues in the charts – all created by himself, – when you know how to solve them they lead to a remote island in the Pacific. and no, NOT Oak Island

Phil Edwards

In the mid 1950s as a adolescents’ I had a opportunity to search for Kidd’s treasure multiple times off the shore of Connecticut in the long Island sound in particularly Money Island witch is one of the most outer islands in a group called the Thimble Islands ,Stony Creek, CT. In Kidd’s time he had definitely anchored off these islands as they all have names associated with him. In fact one is named after him Kidd island . My cousin still owns property on Money island a great place to start a treasure hunt.

Gerry Burnie

A really excellent presentation, Hammerson.

I have posted it to my FB page, In Praise of Canadian History [https://www.facebook.com/InPraiseOfCanadianHistory/]. It has about 50 visitors a day, and is open to posts by others, so perhaps you might find it advantageous to share your posts there.

Hope all is well personally. G.

Hammerson Peters

Thanks Gerry! I really appreciate that.