The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 15

Continued from The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 14.

Across the Prairies

On January 1, 1776, Alexander Henry decided to visit the westerly prairies. Accompanied by two French-Canadians, Henry snowshoed to Cumberland House, struggling through deep snow and suffering bitterly cold temperatures. In addition to his two employees, Henry was accompanied on this first leg of the journey by Joseph Frobisher, whom, he wrote in gratitude, “is certainly the first man that ever went the same distance in such a climate and upon snowshoes to convey a friend.”

Henry and his men snowshoed across Cumberland Lake and continued up the Saskatchewan River. The temperature was so cold that the explorers were obliged to sleep huddled together on the same buffalo robe. When the travellers ran out of provisions, Henry produced a bar of chocolate that he had saved for such an occasion. The men gradually consumed the confection by dissolving a square at a time onto a pot of hot water and drinking the liquid. They subsisted on this weak hot chocolate for several days, nearly succumbing to starvation, when they stumbled upon the bones of an elk recently devoured by wolves. “Having instantly gathered them,” Henry wrote, “we encamped, and filling our kettle, prepared ourselves a meal of strong and excellent soup. The greater part of the night was passed in boiling and regaling on our booty, and early in the morning we felt ourselves strong enough to proceed.”

On January 25th, Henry and his men reached the edge of the Canadian prairies. There, they found the whole frozen carcass of a red deer, which appeared to have become stuck in the river ice at the onset of winter. The adventurers removed as much meat from the carcass as they could and enjoyed their first good meal since Cumberland House.

On the morning of January 27th, Henry and his men came upon a pair of day-old snowshoe tracks. They followed the tracks and arrived at a fur trading post called Fort des Prairies, also known as Fort de la Corne, that evening. There, the fort’s occupants treated Henry and his employees to a bountiful feast of buffalo bull tongues.

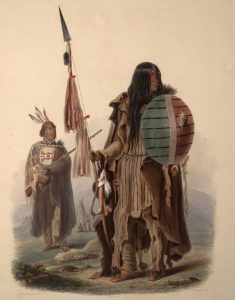

A band of Assiniboine Indians were also visiting Fort de la Corne at the time. Hoping to more thoroughly experience the prairies, and perhaps see the Rocky Mountains beyond, Henry asked the Assiniboine if he might accompany them to their village. The natives agreed, and thus Henry, along with his two French-Canadian employees and two English fur traders named Patterson and Holmes, set out with their new native companions in early February.

The Europeans followed the Indians up to a high plateau where trees were sparse. They struggled to keep up with the natives, who wore narrower snowshoes than them, and who had loaded much of their supplies onto dog-drawn travois. They stopped and made camp at sunset. “The tent in which I slept,” Henry wrote, “contained fourteen persons, each of whom lay with his feet to the fire, which was in the middle; but the night was so cold that even this precaution, with the assistance of our buffalo robes, was insufficient to keep us warm. Our supper was made on the tongues of the wild ox, or buffalo, boiled in my kettle, which was the only one in the camp.”

The following day, Henry and his companions followed the Indians across the open prairie. When a snow storm threatened to descend upon them, they took shelter in a small isolated copse of trees and shrubs, the trunks of the largest of which did not exceed a man’s wrist in diameter.

The party resumed their journey the next day, finally making camp on the shores of a frozen lake. There, they were approached by scouts sent by Great Road, the head chief of the Assiniboine, who had had sent them to search for the band, worried that something might have befallen the travellers on their journey to the east. The scouts were pleased to find Henry and his companions among the Assiniboine, telling them that their chief would be interested in meeting them.

The travellers and the scouts spent the next few days encamped beside the lake, where they waited out a storm that nearly buried their teepees in snow. At the height of the blizzard, the wooded oasis was invaded by a herd of buffalo which might have trampled the camp had it not been for the barking of the Indian dogs and the shooting of the Assiniboine hunters, the latter killing any animal which ventured too close to their teepees with bows and arrows. “Whatever were the terrors which filled the wood,” Henry wrote, “[the buffalo] had no other escape from the terrors of the storm.”

When the storm finally abated, the scouts set out for the camp of Great Road bearing gifts of tobacco and vermillion with which the Europeans had supplied them. The rest of the travellers followed more slowly, burdened by their equipment and provisions.

The Assiniboine Camp

The travellers reached the camp of Great Road on the morning of February 11th, 1776. Henry and his men were greeted by an honour guard, whose members ushered them into a tent which had been set aside for their use. There, Assiniboine women presented them with warm water for washing. “The refreshment was exceedingly acceptable,” Henry wrote, “for on our march we had become so dirty that our complexions were not very distinguishable from those of the Indians themselves.”

Following their ablutions, the Europeans were taken to Great Road’s tent. Henry described the great Assiniboine chief as standing about 5’10’’ and having a darker complexion than most of his fellow tribesmen. Great Road’s most peculiar physical attribute was his hair, which he wore in long, wild, matted dreadlocks. Henry learned that the chief never cut or groomed in accordance with a peculiar Samson-esque superstition he held; Great Road believed that his hair was the source of his fortune and power.

When the guests entered his teepee, the head chief shook each of their hands and invited them to sit on bearskins which had been spread on the ground. Great Road then produced a pipe, which everyone in attendance proceeded to smoke. The chief then made a long and eloquent speech, following which every Indian in the teepee began to weep. Henry was told later that the Indians practiced this custom in honour of their deceased relatives, memories of whom invariably surfaced at the commencement of feasts and ceremonies. The weeping continued for ten minutes, and when it ended, the Indians feasted their guests on boiled buffalo tongue. Henry and his companions were invited to a second feast later that night, in which all the Assiniboine men, due to the warmth of the fire, stripped entirely naked, to some of the white men’s amusement.

The following day, after Henry and his companions toured the village, Great Road delivered another speech in which he informed the Europeans that he was at their service, and that he planned to visit Fort de la Corne at the earliest opportunity. He then gave his guests a gift of beaver pelts and wolf furs, prompting the travellers to present him with more tobacco and vermillion.

Henry and his companions spent five more days in the camp of the Assiniboine. Although they had liberty to go about the camp as they pleased, they were guarded at all times by six warriors who savagely thrashed anyone who came too close to them.

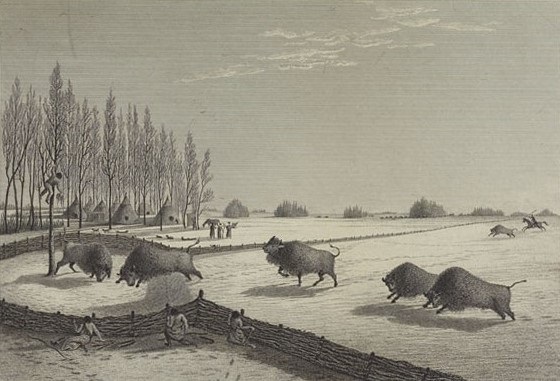

During their say, the Assiniboine invited the Europeans to accompany them on a buffalo hunt. Henry described how the Assiniboine had built a fence, or buffalo pound, about five miles from the camp many years ago. The v-shaped enclosure consisted of birch stakes through which smaller branches were woven. Once the pound was sufficiently repaired, a handful of Assiniboine hunters donned buffalo robes with horns. “Their faces were covered,” Henry wrote, “and their gestures so closely resembled those of the animals themselves that had I not been in the secret I should have been as much deceived as the oxen.”

These special hunters spent most of the evening luring the buffalo towards the pound, successfully convincing their quarry that they were bison calves by mimicking their sounds and behavior. Slowly but steadily, the hunters lured the buffalo herd into the enclosure, finally slipping out of the pound through a hidden gate at its end. The rest of the warriors, meanwhile, concealed themselves behind the pound walls. On a prearranged signal, the hunters emerged from their hiding places and began to shower the buffalo with arrows. Whenever any of the animals attempted to escape the pound, a hunter would wave a buffalo robe in its face, prompting the creature to scramble backwards. The morning following the slaughter, the carcasses were processed, the tongues, hearts, and shoulders being set aside for feasts and the remainder dried for future use, and for sale at Fort de la Corne. The Assiniboine spent the rest of the day and much of the night feasting, dancing, singing, and making music.

“The [musical] instruments,” Henry wrote, “consisted principally in a sort of tambourine, and a gourd filled with stones, which several persons accompanied by shaking two bones together; and others with bunches of deer hoofs, fastened to the end of a stick. Another instrument was one that was no more than a piece of wood of three feet with notches cut on its edge. The performer drew a stick backward and forward along the notches, keeping time. The women sang; and the sweetness of their voices exceeded whatever I had heard before.”

Continued in The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 16.

Leave a Reply