The Cursed Lighthouse of Bird Rock

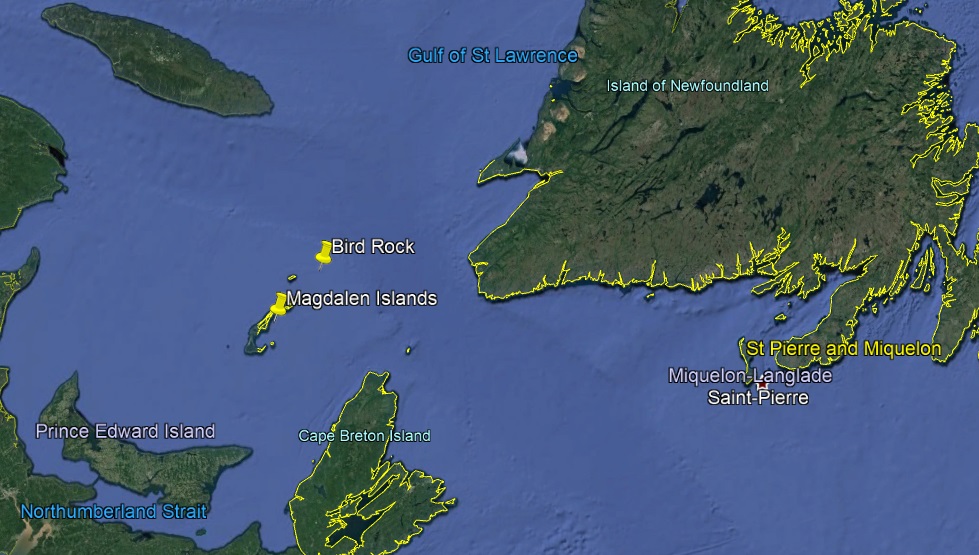

Every day, freighters passing through the Cabot Strait- the waterway between Newfoundland and Cape Breton, which separates the Gulf of St. Lawrence from the greater Atlantic Ocean- float by a bleak, windswept isle known as Rocher aux Oiseaux, or Bird Rock. This five-acre islet is an outlying member of the Magdalen Islands, a hook-shaped archipelago in the Gulf of St. Lawrence which, despite being closer to Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, actually belongs to the province of Quebec.

In the summer, Bird Rock- along with its northwesterly sister, a nearby cluster of sea rocks called Rocher aux Margaux (which bears the name that Jacques Cartier gave to Bird Rock in June 1534; “margaux” being the 16th Century French word for gannets), or the Little Bird Rocks- is a birdwatcher’s paradise. Back in 1917, the island and its surrounding waters was designated the Bird Rocks Bird Sanctuary, making it the oldest migratory bird sanctuary in Canada. Today, in the height of summer, nearly every nook and cranny of its 30-metre-tall red sandstone cliffs is occupied by some variety of migratory seabird, from petrels to gulls to razor-billed auks. In addition to being a refuge for some of the North Atlantic’s most threatened avian species, ornithologists estimate that Bird Rock annually hosts up to 47,000 Northern gannets- nearly a quarter of this species’ population in North America.

One writer who visited the isle in the summer of 1932 recalled an incident which serves to illustrate the completeness of the dominion which Bird Rock’s feathered denizens hold over the place in the summer months:

“Suddenly, a great swarm of gannets took wing with a rumble like a thunderstorm. An enormous white cloud of them, hundreds of yards in extent, swooped overhead. It had the odd effect of a snowstorm suspended in mid-air. So dense were they that a battery of machine guns would have had no effect.”

Every autumn, Bird Rock’s eponymous avian occupants migrate south to warmer climes, leaving Rocher aux Oiseaux silent and desolate. The strident squawks which characterized the spring and summer are replaced by the softer yet equally-incessant crashing of the waves against the island’s circumferential cliffs, and the pervasive stench of bird droppings which hung heavily on the summer air gives way to an equally-heavy winter mist, punctuated by the occasional ghostly wail of a foghorn. In this gloomier state, Bird Rock seems more accordant with its morbid history and the shroud of superstition that surrounds it. For atop grassy plateau of Rocher aux Oiseaux, so say the seafaring folk of the Magdalen Islands, dwells a terrible curse.

The Lighthouse

Since the earliest years of New France, Bird Rock and rest of the Magdalen Islands posed a deadly hazard to the crews of European sailing ships entering the Gulf of St. Lawrence from the Atlantic Ocean. Vessels sailing through the Strait of Cabot at night, or in heavy fog, ran the risk of smashing to matchwood against the merciless cliffs of the Magdalens, and throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries, hundreds of ships met their ends in this manner. Passengers and crewmembers aboard these ill-fated vessels who managed to avoid the one-way trip to Davy Jones’ Locker climbed atop the islands and anxiously awaited their rescue, often in vain. Today, most Madelinots, as inhabitants of the Magdalen Islands are called, are descendants of these shipwreck survivors, and many of the islands’ oldest buildings are constructed from timber salvaged from the ships she claimed.

In 1827, a Captain of the Royal Navy named Edward Boxer wrote the following to the Grand Admiral of Maritime Britain:

“I have found a great need for lighthouses in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. On this sea, navigation is so dangerous because of strong and irregular currents, and there is not a single lighthouse in all the Gulf. It is truly lamentable to find so many shipwrecks at different places on the coast… the number of lost lives is very large and certainly incalculable…”

It would be over four decades before Boxer’s recommendation was acted upon. In 1860, John Page, the Chief

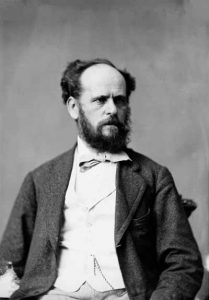

Engineer for the Province of Canada’s Department of Public Works, proposed the erection of a lighthouse on Rocher aux Oiseaux, as Bird Rock was the closest of the Magdalen Islands to the Laurentian Channel- the underwater valley which follows the natural route through the Cabot Strait. In 1869, the fledgling Dominion of Canada decided to follow Page’s advice. That year, contractors sailed out to the island and set about constructing a 15.2-metre-tall wooden lighthouse on its plateau, somehow managing to haul their supplies up and over the Rock’s 30-metre walls. Finally, in 1870, Peter Mitchell, a Father of Confederation who served as the Dominion’s Minister of Marine and Fisheries, reported:

“I feel much pleasure in stating that at Bird Rocks, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence- the most difficult place in the Dominion on which to erect a lighthouse, owing to the surf which continually breaks around it, and the danger of approaching it and effecting a landing thereon- the effects of the Department have been entirely successful in erecting a lighthouse and buildings in connection therewith.”

The Prediction

The story of the early years of the Bird Rock Lighthouse is shrouded in mystery. According to legend, the lighthouse’s first keeper was a Frenchman named Jacques Guitte. After tending the lonely lighthouse for two years, “solitude,” as a contemporary newspaper article put it, “preyed so upon his mind that he went insane.”

Before being hauled away to an asylum, Guitte is said to have uttered the following prophecy:

“No man will keep this lighthouse for more than ten years without meeting misfortune.”

None but the local Acadians of the Magdalen Islands thought there was any chance that Guitte’s prediction might come true.

Peter Whalen and his Son

Guitte’s successor, a man named George Preston, did not tend the Bird Rock Lighthouse long enough to put his predecessor’s prediction to the test. After only a few months on Rocher aux Oiseaux, Preston was removed from his position- according to some versions of the story, in a straightjacket- on the premise that he was mentally infirm.

Preston was immediately succeeded by Peter (or perhaps Patrick; not to be confused with the alleged assassin of a similar name who was hanged four years prior at the Ottawa Jail gallows) Whalen, who moved to the island with his wife and son in 1873. That same year, government workers installed a cannon on the island, which was to be fired at regular intervals during heavy fog in order to warn ships to steer clear of Bird Rock and the Magdalen Islands.

For seven long years, the Whalen family dutifully served as the keepers of the Bird Rock Lighthouse. Then, one day in early April, 1880, Peter Whalen, the former’s son, and an assistant lighthouse keeper named Thomas Thivierge went hunting for harp seals, one of the few pastimes that their occupation afforded them. To the dismay of Mrs. Whalen, who was left to tend the lighthouse in the men’s absence, the three men failed to return that night.

The following day, Thomas Thivierge, sopping wet and chilled to the bone, stumbled onto Bird Rock and staggered towards the lighthouse. Through chattering teeth, he informed a distraught Mrs. Whalen that her husband and son had perished the previous night. While the men were out on the water hunting for seals, a storm had blown in quite unexpectedly and tossed the three of them onto an ice flow. Unable to return to their boat before dark, the men decided to spend the night on the ice. Before dawn, Peter Whalen and his son had froze to death.

The Tragedy of 1881

Peter Whalen and his family were succeeded by Charles Chiasson, a local Madelinot from the nearby island of Havre-aux-Maisons. In 1880, Chiasson, his wife, and his son Cyrice moved onto Bird Rock. They would not last two years.

In the summer of 1881, a friend of the Chiasson family named Paul Chenell came to Bird Rock for a visit. He was accompanied by his ten-year-old daughter Sarah and a man named Jean Turbide- a relative of the assistant keeper, Telesphore Turbide.

August 23, 1881, was a particularly foggy day on Bird Rock, and Charles Chiasson was obliged to fire the fog cannon. As this was the first occasion he had to use the device since his guests’ arrival, Chiasson invited Paul, Sarah, and Jean to watch the procedure.

August 23, 1881, was a particularly foggy day on Bird Rock, and Charles Chiasson was obliged to fire the fog cannon. As this was the first occasion he had to use the device since his guests’ arrival, Chiasson invited Paul, Sarah, and Jean to watch the procedure.

Chiasson’s usual custom when preparing the fog cannon was to load the gun with powder retrieved from a barrel kept in a storage shed. For some reason, however, on this particular occasion, the powder barrel stood a short distance from away the cannon with its lid open. Without thinking to move the keg back to the shed and out of harm’s way, Chiasson decided to fire the cannon.

When Chiasson lit the fuse, a spark landed in the powder keg and a tremendous explosion rocked the island. Chiasson and his son, Cyrice, who had assisted with the procedure, were killed instantly. Paul Chenell was severely wounded, and succumbed to his injuries several hours later. Jean and Telesphore Turbide escaped with minor injuries despite Jean’s having been blown off a cliff and into the sea by the blast’s shockwave, and young Sarah Chenell, though frightened half to death, was physically unharmed.

The Tenure of Telesphore Turbide

Following the death of Charles Chiasson, assistant keeper Telesphore Turbide was put in charge of the Bird Rock Lighthouse. In 1887, he oversaw the construction of a new, six-sided, 11.9-metre-tall wooden tower.

By the summer of 1891, Turbide had manned Rocher aux Oiseaux for nearly a decade- far long than any previous keeper. It seemed that he was well on his way to beating the curse of Bird Rock. If he managed to serve until August 23rd, the tenth anniversary of Chiasson’s death, without serious mishap, Guitte’s chilling prophecy would prove nothing more than the deluded ravings of a madman.

On June 24, 1891, two months before this deadline, the island decided to exact its toll on the hapless keeper. It was a foggy day, and Telesphore Turbide was obliged to fire the cannon. The lighthouse keeper poured a charge of powder down the barrel, tamped it down, and lit the cannon’s fuse. Mysteriously, the cannon failed to fire. Thinking that he may have done a poor job tamping the powder, Turbide inserted the cannon’s ramrod back into the muzzle. At that moment,

the cannon suddenly discharged, hurling the keeper twenty-five feet across the plateau and blowing off most of his right hand. A shell-shocked Turbide doctored his mangled hand as best he could, flagged down a passing ship, and went to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, for medical treatment.

Following his recovery, Telesphore Turbide returned to his post at Bird Rock, where he would serve for another five years. In 1895, he managed to convince Canada’s Department of Marine and Fisheries to replace the dangerous fog cannon with a safer cotton powder cartridge gun.

Turbide’s third and final brush with the island’s curse took place in September 1896. One day, while receiving a shipment of supplies from the mainland, the crane used to haul the cargo onto the island’s plateau fell on top of him, crushing his legs. Not daring to defy the curse any longer, Turbide resigned from his position and was granted a lifetime annual allowance of $180 by the Canadian government. In total, Telesphore Turbide served an incredible fifteen years as head lighthouse keeper of Rocher aux Oiseaux- longer than any keeper before or since.

Arsene Turbide and the Tragedy of 1897

Following Telesphore Turbide’s resignation, a man named Pierre Bourque was appointed as the next keeper of the Bird Rock Lighthouse. As Bourque was unable to take the position until spring, it was arranged for Telesphore’s cousin, Arsene Turbide, to man the lighthouse that winter.

In March 1897, shortly before Bourque’s scheduled arrival, Arsene Turbide, 17-year-old Charles Turbide (Telesphore’s son), and assistant keeper Damien Cormier decided to go seal hunting. Their fate was eerily similar to that of Peter Whalen and his party, who froze to death on an ice floe seventeen years prior.

Like their ill-fated predecessors, the three men were beset by an unexpected storm. Charles Turbide and Damien Cormier did not survive the night.

Miraculously, Arsene Turbide managed to make his way across sixty miles of sea ice to the fishing community of Bay St. Lawrence, Nova Scotia, on Cape Breton Island- a journey which he accomplished in three days. Turbide was taken to a hospital, where he expressed deep concern for the wife of Damien Cormier, who was alone on Bird Rock. A government icebreaker was subsequently dispatched to rescue Cormier’s widow.

Arsene Turbide died in bed fifteen days after arriving at Bay St. Lawrence.

Pierre and Wilfrid Bourque

In May 1897, two months after the tragedy, Pierre Bourque took up his post at Bird Rock as scheduled. Almost immediately, he was plagued by misfortune. After only a few weeks, his assistant keeper, a man named Hippolyte Melanson, injured himself severely while firing the fog cartridge gun. Following the accident, Melanson was replaced by Bourque’s son Wilfrid.

In 1905, after eight years of service, Pierre decided to relinquish his position as head lighthouse keeper to Wilfrid. The younger Bourque, whose wife and children moved onto the island with him, made it his mission to improve conditions on Bird Rock. In 1906, he replaced the fog cartridge cannon with a far safer three-inch diaphone fog signal. In 1908, he reinforced the lighthouse with concrete and raised its height to 15.2 metres. That same year, he asked the Department of Marine and Fisheries to extend a telegraph line to Bird Rock. His request was denied.

On March 11, 1912, after tending the Bird Rock Lighthouse for seven years, Wilfrid Bourque grabbed his shotgun and headed out to hunt some seals he spotted in an opening in the ice not far from the island. When Bourque failed to return, his wife sent assistant keeper Daniel Turbide (a relative of Telephore and Arsene) and her nephew, Elphege Bourque, to search for him. The two men found Bourque’s lifeless body standing upright in the water near the edge of the ice. Bourque’s poor widow was forced to both perform her motherly duties and tend the lighthouse in her husband’s stead for ten days while waiting for relief.

Elphege Bourque

Wilfrid Bourque was succeeded by his nephew, Elphege- now a seasoned lighthouse veteran.

While serving under his uncle, Elphege had grown weary of the simple unperishable fare that was part and parcel of lighthouse life. One day, he decided to bring a milk cow to the island. With considerable difficulty, the keeper managed to transport the animal to the Rock and hoist it up onto the plateau. Shortly thereafter, Elphege had his second encounter with the curse of Rocher aux Oiseaux; after only six weeks, his cow went insane and jumped over a cliff to its death.

Elphege managed to tend the lighthouse at Bird Rock for ten quiet years, enduring no greater tragedy than the loss of his milk cow. It seemed as if the curse had finally left Rocher aux Oiseaux for good.

Suddenly, as if to make up for its decade of indolence, the jinx of Bird Rock reared its ugly head once again and lashed out at its tenants with a nigh unprecedented ferocity.

In the fall of 1922, Elphege Bourque decided to take a vacation. He left the lighthouse in the charge of his brother Albin and assistants Philias Richard and Octave Langford. Shortly after Albin arrived on the island to relieve his brother, all three men became deathly ill, apparently having consumed rainwater contaminated with diseased bird droppings. The men managed to flag down a ship destined for Charlottetown, but by that time it was too late. Albin died en route to Prince Edward Island, Richard died shortly thereafter, and Langford became paralyzed for life from the waist down.

The End of the Curse

Following the death of his brother, Elphege Bourque left Bird Rock, never to return. Lighthouse duties were immediately assumed by a family of Acadians by the name Arsenault.

The first Arsenault to man the Bird Rock Lighthouse was J. Montague Arsenault. Montague served as head keeper for fifteen years, soundly belying Guitte’s prediction. After the successful five-year tenure of a man named J. Marc Richard, another Arsenault named Alfred A. took up his predecessor’s mantle. One writer who visited Rocher aux Oiseaux in 1950 wrote:

“When Alfred Arsenaut [sic] had finished telling me the story of Bird Rock, I asked him if he worried about the prophecy. He shrugged.

“As I looked at Arsenaut’s [sic] quiet, sturdy face I had the sudden thought: ‘This quiet man can defeat the prophecy!’ Only time will tell.”

Sure enough, Alfred Arsenault served a mercifully uneventful twelve years as head keeper of the Bird Rock Lighthouse before retiring in 1955.

Aside from a lightning-induced fire which reduced some of the service buildings to ashes in 1955, when the lighthouse was under the care of Alfred’s relative Elzear Arsenault, Bird Rock never again subjected its residents to another catastrophe. Following Elzear’s resignation in 1959, eleven different keepers successfully manned the lighthouse of Rocher aux Oiseaux, none of them serving for more than four years.

In 1967, the lighthouse was replaced by a new 31-foot hexagonal concrete tower, and in 1988, the tower was automated, leaving Bird Rock for the birds. Today, the lighthouse of Rocher aux Oiseaux operates on its own, as if manned by ghostly keepers. Its eerie desolation serves as a chilling reminder of the deadly curse which haunted its inhabitants for more than fifty years.

Sources

- Haunted Island: Strange Legend Clings to Lonely Bird Rock; by Richard Harrington; in the November 19, 1950 issue of the Washington Post’s supplement magazine Parade; courtesy of American Fortean researcher Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- Bird Rock; by Beverley Owen; in the January 1, 1933 issue of Maclean’s magazine

- The Mysterious Magdalens; by Beverley Owen; in the December 1, 1932 issue of Maclean’s magazine

- The Cursed Lightstation of Rocher aux Oiseaux: A Malicious Prank of Nature; by Jeremy D’Entremont; in the May 2004 issue of the Lighthouse Digest Magazine

- Rocher aux Oiseaux (Bird Rock) Lighthouse, on LighthouseFriends.com

- Magdalen Islands Shipwrecks, by Rupert Taylor in the August 14, 2017 issue of OwlCation.com

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Sylvie Lafrance

The photo “Bird Rock Lighthouse” (The Cursed Lighthouse of Bird Rock) is not the good one. It’s Brion lighthouse.

Bailey Douesnard

Thank you for this very interesting and informative article! However, I will note that “Following Elzear’s resignation in 1959, eleven different keepers successfully manned the lighthouse of Rocher aux Oiseaux, none of them serving for more than four years” is incorrect as my grandfather, Jim McLean was the longest serving ligthouse keeper at Birdrock from 1962 until its automation in 1987.

Hammerson Peters

Thanks for the heads up! I can’t remember which source I got that info from. Very cool.