The Adventures of Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

In the summer of 1803, the French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte sold an enormous province known as French Louisiana- a vast territory which stretched from the Rocky Mountains of present-day northern Montana to the bayous of New Orleans- to the United States for fifteen million dollars. This transaction, known as the Louisiana Purchase, has been described as one of the greatest real estate deals in history.

Although many students of North American history are at least tangentially familiar with the Louisiana Purchase, relatively few are acquainted with the founder of the territory in question, a chronically luckless French adventurer named Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, who deserves a place in Canadian memory if only for the stoic tenacity with which he addressed the obstacles, setbacks, and misfortunes which perpetually plagued his short and exhilarating life.

Jesuit Training

Rene-Robert Cavelier was born on November 21, 1643, in Rouen, an ancient Norman city situated on the River Siene. His family, which belonged to France’s burgeoning middle class, sent him to study with the Jesuits. Rene-Robert was ordained as a Jesuit priest in 1660 and tasked with studying logic and mathematics- subjects in which he excelled- at a Jesuit college in the southwesterly town of La Fleche. He went on to teach these subjects to Jesuit novices in various French colleges.

Rene-Robert was imbued with a restless nature which he hoped to satisfy through foreign missionary work. When his superiors denied his repeated entreaties to be sent overseas, he asked them to release him from his vows on account of his self-proclaimed “moral frailties”. His superiors acquiesced, and the spring of 1667, Rene-Robert left the Jesuit Order.

New France

Using a fraction of what little money he had, the ex-priest booked passage aboard a ship bound for France’s burgeoning New World colony, New France, where his elder brother, a Sulpician priest, had relocated the previous year. Upon arrival, he travelled to Fort Ville-Marie- a French settlement near the town of Montreal which was administrated by missionaries of the Sulpician Order- and spent the remainder of his meagre fortune on a seigniory, or strip of farmland, situated on the banks of the St. Lawrence River on the Island of Montreal. Along with his land, Rene-Robert Cavelier received the title Sieur de la Salle, or “Lord of the Manor”- an honorific by which posterity would remember him.

Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, immediately began renting out his new land to settlers, establishing an as-yet-unnamed village on the southern shores of the Island of Montreal. He spent the next few years making sporadic trips to various northern native villages, immersing himself in the dialects of the local First Nations.

The Ohio Expedition

In the winter of 1668/69, La Salle was visited by a band of Seneca Iroquois, whom he hosted for much of the season. The natives told the young Frenchman of a southerly river called the Ohio, which flowed into a distant southwesterly ocean. La Salle hoped that the Ohio might constitute the fabled Northwest Passage- a hypothetical shipping route through North America to China- and suspected that the sea into which it flowed might be the Gulf of California, on the Pacific Coast. Hungry for adventure and a chance to prove his worth, he began planning an exploratory expedition to the Ohio River.

That spring, la Salle travelled to Quebec City and asked the Governor of New France, Daniel de Remy de Courcelle, for permission to carry out his enterprise. The Governor granted his request, giving La Salle license to explore the Ohio River on the condition that he finance the venture himself. The 26-year-old adventurer promptly sold his seigniory to the Sulpicians and a local blacksmith, using the money from the sale to purchase four canoes, an outfit of supplies, and wages for fourteen men.

Around that same time, the local Sulpician missionaries were planning a similar expedition to the Ohio River for the purpose of converting its natives to the Catholic faith. One of their members, a robust French cavalry officer-turned-priest named Francois Dollier de Casson, had spent the previous winter with a band of Anishinaabe Indians on the shores of the westerly Lake Nipissing. The band’s chief owned a young slave who hailed from the south, who told Casson tales of a mighty river to the south populated by large tribes whose ears had never heard the Word of God. Casson resolved to find these tribes and spend the rest of his life teaching them the Gospel and ministering to their spiritual needs. The missionary made his own entreaty to Governor Courcelle, who requested that he join La Salle’s expedition. Casson and a fellow Sulpician- a novice astronomer and mathematician named Rene de Brehant de Galinee- hired three canoes and seven men and joined La Salle’s party.

Lake Ontario

The explorers, accompanied by a handful of Iroquois guides and a Dutch interpreter, set out on their expedition to the Ohio River on July 8, 1669, beginning their journey at La Salle’s former seigniory. They paddled their canoes up the St. Lawrence River, through the archipelago known as the Thousand Islands, and into Lake Ontario, battling privation and illness all the way. During this first leg of their voyage, the explorers learned that La Salle had a poor grasp of the Iroquois languages, contrary to his prior claims of perfect fluency.

The explorers reached Lake Ontario on August 2nd and paddled along its southern shore. At the mouth of what they called the Karontagouat River (probably what is known today as Irondequoit Bay, fed by the Irondequoit Creek beyond), they met with a band of Seneca Iroquois. La Salle’s knowledge of the Iroquois language was so minimal that he could not converse with the natives, and the explorers’ Dutch interpreter had such a poor grasp of the French language that he could not adequately convey the Iroquois’ messages to his employers. Fortunately, the Seneca were accompanied at that time by the servant of a Jesuit missionary named Jacques Fremin, who offered to lend his interpretive services to the explorers; Fremin himself was away attending a Jesuit meeting at Onondaga, a large village which served as the capital of the Iroquois Confederacy. Although Fathers Casson and Galinee suspected that their Jesuit rival deliberately misinterpreted their words in an effort to thwart the Sulpician cause, Fremin’s servant managed to convey the explorers’ desire to hire a guide who knew the way to the Ohio River.

The Seneca were reluctant to help the explorers reach the Ohio, the territory of their enemies, perhaps suspecting that the French might form an alliance with their southerly foes. They repeatedly warned the Dutch interpreter not to travel to the Ohio, telling him that the Indians that lived along its shores were hostile and would surely kill him and his employers. One of the prisoners the Iroquois held in their camp at that time was a young warrior from the west who could easily have guided the Frenchmen to their destination. Rather than hand this brave over to the explorers, the Seneca tortured him to death, slowly searing his skin from head to toe with a red-hot musket barrel before forcing him to run a gauntlet through the village, showering him with hot coals and prodding him with lit torches all the while. When the ritual execution was complete, the natives dismembered the prisoner’s corpse, cooked his flesh in a kettle and devoured it, inviting the horrified Frenchmen to partake in the grisly feast.

Finally, after spending a month in the Seneca village, the explorers met a travelling Iroquois who agreed to take them to his own village at the head of Lake Ontario. There, he assured them, they would easily find a guide who would take them to Lake Erie and the Ohio River beyond. The explorers accompanied the Indian along the southern shore of Lake Ontario, past the mouth of the Niagara River, where they could hear the roar of the distant Niagara Falls, to his village on the shores of Burlington Bay, not far from the present city of Hamilton, Ontario.

Upon reaching the village, La Salle came down with a debilitating fever; according to Galinee in a later reminiscence, this malady may have struck La Salle when he saw three large rattlesnakes in his path while climbing a rock. This setback was mitigated by the news that another Frenchman had just arrived at a more northerly Iroquois village. The explorers hiked north to the settlement in question, where they met a young French adventurer named Adrien Jolliet. Jolliet informed the explorers that the Governor had tasked him and his fellow explorer, Jean Pere, from whom he had since separated, with locating the rich copper mines which were said to lie on the shores of Lake Superior. Jolliet was returning from this failed expedition and had decided to take a circuitous route back to Quebec on account of his Indian guide’s fear of the natives who inhabited the shores of the Niagara River.

Jolliet regaled the Sulpician missionaries with tales of the Pottawatomi Indians who inhabited the shores of Lakes Michigan and Superior, and who were in dire need of Christian ministry. The explorer’s tales had such an effect on the Sulpician fathers that they decided to abandon their search for the Ohio River in favour of bringing the Gospels to the Pottawatomi. La Salle, who still hoped to discover the Northwest Passage, used his newly-developed fever as a pretext to separate from the missionaries, encouraging them and their crew to carry on without him.

Lachine

Fathers Casson and Galinee and their crew of seven portaged southwest through the forest to what is known today as the Grand River and followed that waterway to Fort Erie, hoping in vain that they might reach the territory of the Pottawatomi before winter. In fact, they made it as far as Lake Erie’s northern shore when the lake began to freeze, forcing them to winter there.

La Salle’s next course of action remains a mystery to this day. Some historians maintain that he secured a competent guide at the village of Onondaga, made his way to Lake Erie, portaged overland to the headwaters of the Ohio River, and followed that waterway to the Falls of the Ohio near present-day Louisville, Kentucky. Others argue that La Salle couldn’t possibly have made the aforementioned journey and that there is no hard evidence he did so, maintaining instead that he must have wintered somewhere on Lake Ontario, or even on the Island of Montreal. Whatever the case, the explorer had returned to Montreal by the autumn of 1670 with little to show for his efforts. In light of La Salle’s failure to find a route to China, as he had boasted he would, his former seigniory was derisively named “La Chine”, or “The China” (later compounded as “Lachine”).

Fort Frontenac

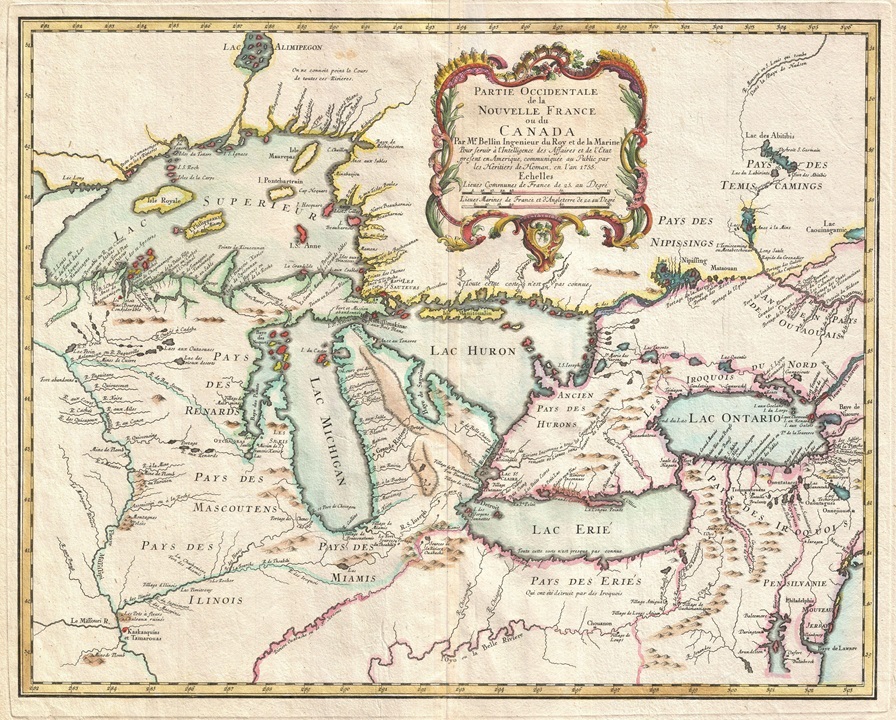

In the autumn of 1672, Governor Courcelle was replaced by Governor Louis de Buade, Compte de Frontenac, a courtier of King Louis XIV and a battle-scarred veteran of both the Dutch War of Independence and the more recent Cretan War. Governor Frontenac was eager to expand the reaches of the colony and inaugurate a new era of prosperity in New France. A year after his appointment, he tasked Louis Jolliet- a Quebec-born Jesuit seminarian-turned-fur trader and the brother of Adrien Jolliet, whom La Salle and company had encountered during their failed expedition in search of the Northwest Passage- with exploring the upper reaches of the great river of which the Jesuits had learned from their Indian congregations: the Mississippi. Jolliet paddled up the Ottawa River and across Lake Huron to St. Ignace, a Jesuit mission located on the mainland near the fur trading fort of Michilimackinac. There, he was joined by five voyageurs and a missionary named Jacques Marquette- a pioneer who had established the St. Ignace mission and the northerly settlement of Sault Ste. Marie, located at the opposite side of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The company paddled their canoes across Lake Michigan to Green Bay. They then travelled south up the Fox River, portaged overland to the Wisconsin River, and followed that waterway south to the Mississippi. During the course of their journey, they met with a number of Indian bands, all of whom insisted on feeding them morsels of food by hand. They also came across a startling riverside pictograph depicting a Piasa Bird- a bearded, horned, scaly, winged monster of native mythology- which appeared to mark the territory of Cahokia Illinois Indians.

During their exploration of the upper reaches of the Mississippi, Jolliet and Marquette learned from the Indians they met that the Mississippi must be the same waterway whose mouth the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto had discovered 130 years prior; it emptied into the Gulf of Mexico, the territory of the Spanish Empire, and not into the Pacific Ocean as they had hoped. Fearful of falling into the hands of the Spanish, they travelled back up the Mississippi, further up the Illinois River, and portaged to the Chicago River, which they followed to Lake Michigan.

While Jolliet and Marquette were undertaking their epic journey towards the Mississippi, La Salle and Governor Frontenac were hatching a plan to expand the French-Canadian fur trade westward and strengthen France’s colonial position in the so-called Pays d’en Haut, or “Upper Country” surrounding the Great Lakes, while lining their own pockets in the process. At that time, the Great Lakes region was dominated by the warlike Iroquois Confederacy- allies of the Dutch and the English who had wiped out or displaced the native Huron, Erie, Neutral, and Petun Nations in the 1640s and ‘50s. The French and their Algonquin allies had warred with the Iroquois throughout the early 1660s, making peace in 1666, just before La Salle’s arrival in New France. Independent French-Canadian fur traders called coureurs des bois, or “runners of the woods”, had since taken their trade to the Iroquois who had recently settled around the Great Lakes, making long canoe journeys through the wilderness to trade knives, hatchets, beads, and other implements to these Indians in exchange for furs. Governor Frontenac conceived of a method by which he might steal this business away from the coureurs des bois for the benefit of himself and the colony, while at the same time protecting New France from future Iroquois incursions and the encroachment of the colony’s English and Dutch rivals: the establishment of a fort on the shores of Lake Ontario. The establishment of such a fort would be a risky endeavor, as King Louis XIV had discouraged the construction of forts and trading posts outside the valley of the St. Lawrence River out of fear that this might spread New France excessively

thin, making it vulnerable to future Iroquois or English attacks. Frontenac, operating on the principal that it better to ask forgiveness than to seek permission, decided to establish the fort without first obtaining the king’s approval. He recruited an eager La Salle to assist him in achieving this end.

Frontenac put his plan into motion by organizing a formal inspection of the French settlements along the St. Lawrence River, from Quebec to Lake Ontario. The secret purpose of this operation was to demonstrate the military might of New France to the Iroquois of the Great Lakes. Using La Salle as his emissary, Frontenac organized a meeting with the great chiefs of the Iroquois Confederacy at the mouth of the Cataraqui River, near the head of the St. Lawrence; the site of present-day Kingston, Ontario.

The meeting between the Governor and the heads of the Iroquois Nations took place in mid-July, 1673. Frontenac arrived at the designated location at the head of a large and impressive compliment of militiamen from Quebec, Montreal, and Trois Rivieres. After exchanging gifts and speeches with the natives, Frontenac met with each of the Iroquois chiefs in his personal pavilion, treating them and their families to fine French food and expressing his regret, through an interpreter, that he did not yet speak their language. In the series of councils that followed, the Governor made it clear to the Iroquois that he desired to maintain the peace they had established, but would make a terrible enemy if provoked. Throughout the course of these meetings, Frontenac’s men hastily constructed a palisaded fortification within sight of the council tent, ostensibly in an effort to impress the Iroquois with their defensive capabilities. The Frenchmen named their new post ‘Fort Cataraqui’.

To the Governor’s delight, King Louis XIV allowed the fort to stand despite its having been constructed without his blessing. In the fall of 1674, La Salle travelled to France and sought audience with King Louis XIV. Armed with a letter of recommendation from Frontenac, he requested that the king appoint him the commander of Fort Cataraqui, which La Salle decided to rename ‘Fort Frontenac’ after his benefactor. King Louis XIV granted La Salle’s request, and the adventurer returned to New France to assume command of his new post and supervise the construction of a stone-and-mortar fortress in place of the palisaded fort. On his return journey, he was accompanied by two Recollect Franciscan friars who were to live at Fort Frontenac, one of them a Fleming named Louis Hennepin.

Fort Conti

Throughout the following few years, La Salle divided most his time between Fort Frontenac and Paris, France. His large market share in the fur trading industry earned him many enemies in New France, resulting in several attempts to entrap him. Once, while visiting a wealthy farmer in Quebec, his host’s wife attempted to seduce him. When La Salle hurried from the room in order to avoid scandal, he found his host on the other side of the door, apparently overseeing the execution of the plot he had orchestrated. On another occasion, a jealous fur trader told a Jesuit priest that La Salle was living with a young unmarried woman at Fort Frontenac. The priest promptly travelled to the fort to rebuke La Salle, where he learned that the rumour was false. In the spring of 1677, a pair of Jesuits missionaries spread a false rumor among their Iroquois congregation that that La Salle was preparing to make war on them; Governor Frontenac himself met with the Indians to allay their suspicions. Shortly thereafter, a famous fur-trader named Nicolas Perrot allegedly attempted to murder La Salle by serving him a salad containing toxic hemlock.

Later that year, La Salle made a trip to France for the purpose of convincing the king to grant him permission to establish two more forts on the Great Lakes- one of them at the mouth of the Niagara River, and the other at the southern tip of Lake Michigan- as well as a sailing vessel on Lake Erie. Louis XIV granted his request, and in July, 1678, La Salle sailed for Canada with thirty men- most of them shipwrights, carpenters, or blacksmiths- and an abundance of supplies. Among his crew were a former French Royal Army officer named Dominique la Motte de Luciere and a one-handed Italian veteran of the Third Anglo-Dutch War named Henri de Tonti, the latter having been recommended to him by his aristocratic friend, Louis Armand, Prince of Conti.

Upon reaching Quebec, La Salle’s crew gained a member in Father Louis Hennepin, one of the two missionaries from Fort Frontenac, who had come to Quebec to intercept La Salle and join his expedition. Other additions to his crew included Martin Chartier, a French-Canadian voyageur who had accompanied Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet on their expedition to the Mississippi, and a Mohegan hunter fluent in a number of Algonquin dialects. Together, the party traveled up the St. Lawrence River to Fort Frontenac.

Upon arriving at the fort, La Salle ordered about half of his men to travel by canoe to Lake Michigan and establish a trading relationship with the natives there. That accomplished, they were to wait for him at Lake Michigan’s Green Bay. He then sent the other half of his employees, including Hennepin and La Motte, to sail in a small ship to the mouth of Niagara River, where he would later build a fort. La Salle himself, along with Henri de Tonti, made a separate trip to a nearby Indian village to secure winter provisions for his crew.

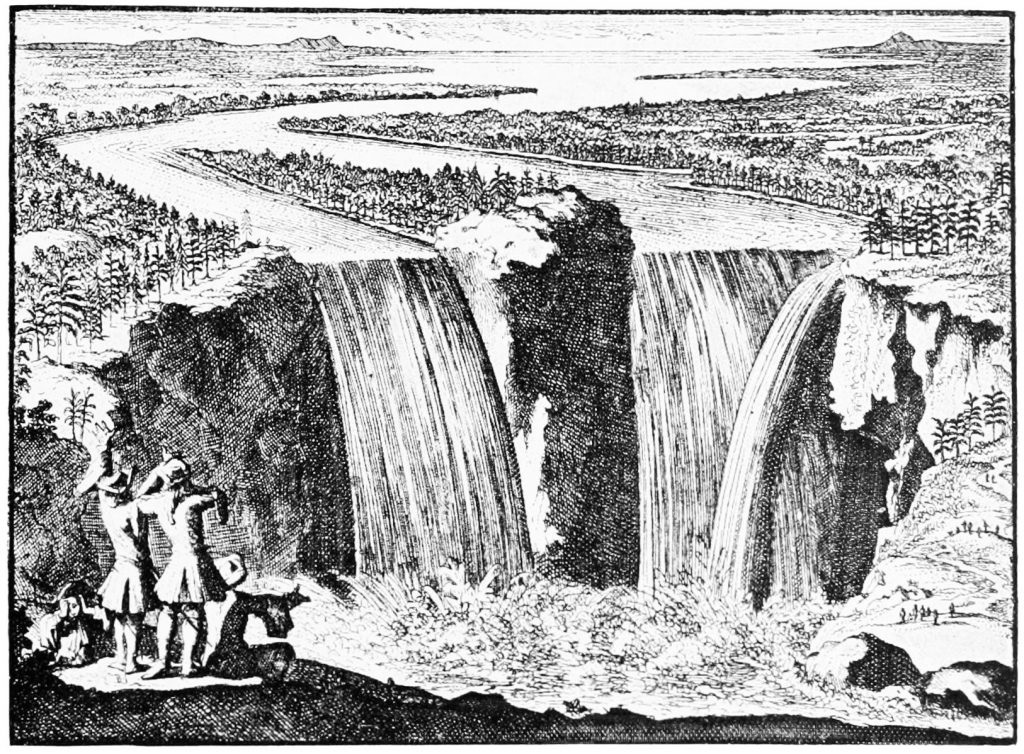

By now, it was late November, the month during which the waters of the Great Lakes are the roughest. Hennepin, La Motte, and company managed to sail their vessel along the northern shore of Lake Ontario to the mouth of the Humber River, near present-day Toronto, before their ship became encased in ice. The adventurers managed to liberate their vessel with axes and make their way across the lake to the mouth of the Niagara River. They disembarked on the river’s eastern shore and made camp. Father Hennepin and a few others, desirous of seen the Niagara Falls, continued up the river in canoes and disembarked at the foot of what is now Queenston Heights, on the western side of the river, with the Niagara Falls in plain view. A few of the explorers then made their way on foot to the western base of the cataract. Excepting, perhaps, a few earlier Jesuit missionaries who failed to write about the experience, Hennepin and his companions thus became the first white men to see the Niagara Falls.

Before laying the foundations for the fort- which La Salle had decided to name ‘Fort Conti’ in honour of his aristocratic Parisian friend- La Motte, Hennepin, and company decided to trek overland to a westerly Seneca village situated near the present site of Rochester, New York, where they hoped to receive the blessing of the local Iroquois chiefs. Although the chiefs were pleased with the gifts the adventurers brought them, they neglected to acknowledge whether or not they would tolerate this new French fort on the banks of the Niagara.

Disappointed by this setback, the adventurers trudged back to the river. Not long after their return, they were joined by La Salle and Tonti, who arrived with building supplies, but had lost much of their provisions during an accident on the lake. La Salle decided to speak with the Iroquois chiefs himself and succeeded in convincing them to approve his enterprise. The adventurers returned to the eastern shores of the Niagara and proceeded to build Fort Conti.

Le Griffon

In January 1679, while the construction of Fort Conti was well underway, a portion of La Salle’s crew hauled a quantity of supplies up the Niagara River and above the Niagara Falls. At the mouth of what is probably Cayuga Creek, they set to constructing a sizeable seven-cannon barque intended for service on Lake Erie.

The construction of this vessel was an unpleasant task for La Salle’s men, who labored with frozen fingers and empty stomachs, all the while wary of the sullen Iroquois braves who frequently loitered around the worksite. While his men worked on the ship and the fort, La Salle himself, accompanied by two of his employees, travelled by snowshoe through the forest and across the frozen Lake Ontario to Fort Frontenac, where he hoped to replenish the provisions he had lost in the lake.

During La Salle’s absence, the men on the Niagara River completed both the fort and the 45-ton ship. The latter was christened Le Griffon, or “The Griffon”, this mythological monster being the primary ornament on Count Frontenac’s coat of arms. Its prow bore a wooden carving of the legendary half-lion/half-eagle for which it was named, and its decks bristled with seven small cannons which were fired at its christening.

La Salle finally returned to the Niagara River in early August, this time accompanied by three more Flemish friars. Eager to make use of the new ship, he and all his men embarked on Le Griffon and set out on her maiden voyage across Lake Erie.

For three days, the explorers sailed down the length of the lake. On the fourth day, they turned north and sailed up the Detroit River. They crossed Lake St. Clair beyond and proceeded up the St. Clair River and into Lake Huron. There, the explorers were beset by a ferocious gale which threatened to capsize their vessel. Praying to St. Anthony of Padua, the patron saint of mariners, the sailors managed to make their way up Lake Huron to the Island of Michilimackinac, a haven for coureurs des bois, home to Huron and Ottawa Indian villages and Father Jacques Marquette’s old Saint Ignace mission.

La Salle and his crew were welcomed cordially by the Jesuits at Michilimackinac, in whose chapel they celebrated Mass. They explorers were subsequently greeted by the local Huron and Ottawa Indians who were amazed at the size of their ship. During their visit, they received the disheartening news that most of the fifteen men whom La Salle had previously sent to establish a trading relationship with the Indians of Lake Michigan had squandered his trading goods and abandoned their mission.

In early September, La Salle and the crew of Le Griffon sailed west from Michilimackinac into Lake Michigan and further southwest into Green Bay. There, on an island, he found the few members of his advance party who had remained loyal to him, discovering to his pleasure that they had acquired a small fortune in furs from their trade with the natives. La Salle then had these furs loaded into the cargo hold of Le Griffon and ordered a handful of his men to transport them to Fort Conti, asking the ship’s pilot to return to Lake Michigan as soon as the cargo was unloaded. Le Griffon departed on September 18th, 1679, just as a storm began to brew. Aside from the vessel’s own crew, La Salle and his explorers were the last men to set eyes on Le Griffon. The vessel was lost with all hands somewhere in the waters of Lakes Michigan, Huron, or Erie. Today, its undiscovered wreck is widely considered the Holy Grail of Great Lakes shipwreck hunters.

Fort Crevecoeur

Leaving a few men behind to await the belated return of Le Griffon, La Salle and his men explored the southern end of Lake Michigan, subsisting on Indian corn and wild game and narrowly avoiding a skirmish with a much larger party of native warriors. In accordance with their royal license, the explorers built a small fort at the mouth of the St. Joseph River at the southern tip of Lake Michigan, which they named ‘Fort Miami’. That accomplished, they travelled up the St. Joseph, portaged to the Kankakee River, and followed that waterway to the Illinois, up which Jacque Marquette and Louis Jolliet had travelled on their return journey to Lake Michigan five years prior.

La Salle and his men followed the Illinois River southwest, leaving the forests of the Great Lakes for the Great Plains. They lived off buffalo, which roamed the prairies in enormous herds, and on some corn that they discovered in the granary of a large abandoned native village, which would become known as the Grand Village of the Illinois. Four years earlier, following his and Louis Jolliet’s expedition to the Mississippi, Father Jacques Marquette had founded a mission at this site, which he named the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin. Shortly thereafter, he had attempted to return to his old mission of St. Ignace, on the Island of Michilimackinac, but had succumbed to dysentery along the way.

Downriver, La Salle and his crew visited a large Illinois Indian camp. The natives attempted to discourage La Salle and his crew from travelling further to the Mississippi- a valley, they claimed, which was populated by hostile Indians; the waters of which were infested with scaly monsters with long snouts and powerful jaws. Six of La Salle’s men heeded the warning and abandoned the expedition, preferring the hardships of the wilderness to the unknown terrors of the Mississippi. La Salle and his remaining men spent the winter if 1679/80 in a palisaded camp they built on the eastern bank of the Illinois River, which they dubbed ‘Fort Crevecoeur’, or “Fort Heartrbeak”.

The Mutiny at Fort Crevecoeur

That February, La Salle’s men began to construct a ship on the banks of the Illinois. This vessel was intended to replace Le Griffon, which the crew now presumed lost with all hands.

While the shipwrights went about their task, a reluctant Louis Hennepin and two of his fellow Recollect missionaries, on La Salle’s orders, headed down the Illinois River with instructions to explore it to its confluence with the Mississippi. Meanwhile, La Salle took a small party back up the Illinois River with the intention of travelling all the way to Montreal for supplies. Along the way, across the Illinois River from the abandoned Grand Village of the Illinois, he noticed a cliff which is known today as ‘Starved Rock’ (perhaps due to the events of a siege which is said to have taken place there during the Seven Years’ War). Believing this site to be an excellent location on which to build a defensive fortress, he sent a message downriver to Henri de Tonti, his most trusted lieutenant, instructing the Italian to construct a fort on top of the cliff, which was to be called ‘Fort St. Louis’.

La Salle and his small party continued to Montreal, crossing the Lower Peninsula of Michigan on foot. On the way, they narrowly avoided massacre at the hands of an Indian raiding party.

In Montreal, La Salle acquired much-needed supplies and prepared to return to his men on the Illinois. Shortly before his departure, while paying a brief visit to Fort Frontenac, he received a letter from Henri de Tonti informing him that, shortly after his departure, nearly all of his men had deserted Fort Crevecoeur, fearing an Iroquois attack. Incited by the voyageur Martin Chartier, they raided the fort’s storehouse of everything they could carry, throwing the rest of the supplies into the river, before destroying the fort itself. The mutineers then retreated to Canada, destroying Fort Miami and plundering the gunpowder at Fort Niagara on the way. Twelve of them were on their way to Fort Frontenac, where they intended to kill La Salle in order to escape his retribution.

La Salle, accompanied by five men, immediately set out to ambush the inbound mutineers. He and his party took the rebels by surprise and captured them, killing two of them in the process. The deserters were placed in custody and delivered to Count Frontenac for trial.

Tonti’s Misadventure

Previously, back on the Illinois River, Henri de Tonti learned of the mutiny at

Fort Crevecoeur while making preparations for the construction of Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock. Accompanied by the three Recollect missionaries who had neglected to partake in the rebellion, he salvaged what supplies he could and took up residence in the abandoned Grand Village of the Illinois. The Illinois band that had previously inhabited the village soon returned and allowed the white men to remain among them. One afternoon, an Illinois scout ran breathless into the village with the alarming news that a war party of Iroquois warriors was inbound. Among their number, he declared, were a Jesuit priest and the explorer La Salle. Although these two characters, in actual fact, were Iroquois war chiefs dressed in black hats and doublets, the scout’s report caused the Illinois villagers to suspect that Tonti and the Recollect missionaries had something to do with the incoming war party. Their suspicions where allayed when Tonti volunteered himself and his comrades to fight alongside the Illinois against the Iroquois.

The Illinois defenders met the Iroquois warriors in a plain outside the village. As the two parties advanced towards each other, Henri de Tonti ran before the warriors and held up a calumet, or peace pipe, in the hope that he might avert the imminent battle. An Iroquois warrior promptly stabbed him in the chest, not realizing that he was a white man. Fortunately, the knife glanced off Tonti’s ribcage, giving the swarthy Italian a deep gash rather than mortal wound. One of the Iroquois chiefs, upon observing that Tonti’s ears were not pierced, deduced that he must be a Frenchman and attempted to doctor his laceration. The Iroquois then argued over whether to scalp Tonti, burn him at the stake, or set him free. After some debate, they sent the Italian back to the Illinois, staggering from his rapid loss of blood and bearing a wampum (clam shell) belt- a token of peace.

Afraid that this gesture constituted an attempt to catch them off guard, the Illinois retreated, abandoning their village to the Iroquois. The Frenchmen remained behind with the Iroquois, with whom France was still officially at peace, and watched as the warriors, bereft of their victory, vented their rage on the village itself. The Iroquois burnt down the Grand Village of the Illinois and dug up its graves, mutilating the corpses of the dead and erecting their skulls on poles.

The Illinois returned several days later, keeping a respectable distance between themselves and their ruined village. The Iroquois sent Tonti to mediate a truce between their two parties, and to convince the Illinois to leave the country. When Tonti accomplished that task, the Iroquois ordered the Frenchmen to head back to New France. Fearing that the natives would murder them all if they failed to comply, the explorers headed up the Illinois River. They proceeded to trudge through the woods all the way back to Green Bay in Lake Michigan, losing the eldest of the friars to a party of Kickapoo warriors who scalped and murdered the Recollect while he was praying alone in a meadow.

Meanwhile, the Iroquois war party followed the retreating Illinois villagers down the Illinois River, watching them from the opposite bank. At the river’s confluence with the Mississippi, the Illinois split into three separate groups, one of which the Iroquois ambushed. Although the Illinois warriors escaped the clutches of the Iroquois, their wives and children were not so fortunate. In a field on the banks of the Mississippi, the Iroquois warriors tortured hundreds of Illinois women and children to death.

Hennepin’s Adventure

While Henri de Conti and the Recollect friars were having their own misadventure at the Grand Village of Illinois, Father Louis Hennepin and two friars were exploring the lower Illinois River and the upper Mississippi beyond. On April 10th, while repairing their canoe on the riverbank in preparation for their journey up the Mississippi, the priests were set upon by a party of canoe-going Eastern Dakota Sioux warriors. After debating amongst themselves, the Sioux decided to take the missionaries captive rather than execute them, as some of their number desired.

The Sioux and their priestly prisoners travelled up the Mississippi River to the site of present-day St. Paul, Minnesota, where they disembarked. From there, they travelled overland to their village on the shores of a northerly body of water known today as Mille Lacs Lake, located about 80 miles southwest of the southwesterly end of Lake Superior.

Instead of burning the friars alive, as Hennepin suspected they might do, the Sioux adopted the Franciscans as their sons. The missionaries were then separated and sent to live with their self-styled fathers in separate villages. In a later reminiscence, Hennepin described how the Sioux, in an effort to restore him to health, his having deteriorated on the grueling journey to the village, treated him in a sweat lodge- a ceremonial steam bath common among the natives the Great Plains and the Great Lakes.

Hoping to return to French-Canadian society, Hennepin told the Sioux that French traders would be arriving shortly at the mouth of the Wisconsin River, on the Mississippi. The Sioux, who were on the brink of starvation, were eager to acquire guns to facilitate hunting and decided to pay these supposed Frenchmen a visit. Taking the friars along with them, they paddled their canoes across Mille Lacs Lake and followed its outlet, the scenic Rum River, to the upper Mississippi about 20 miles upriver from the place at which they had disembarked on their homeward journey. About sixteen miles downriver from this point, near what is now downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, the party came to a waterfall in the middle of the river, which Hennepin dubbed the ‘Falls of Saint Anthony’.

When Hennepin’s adopted father reached the mouth of the Wisconsin River and failed to find any French traders, he admonished the friar for lying but decided to let him live. Hennepin and his religious brothers subsequently travelled down the Mississippi to the Chippewa River, were they participated in a Sioux buffalo hunt. Near the end of the hunt, the Sioux received news that five white men had arrived in Sioux territory from Lake Superior. These men had somehow heard about Hennepin and his fellow friars and were interested in learning more about them. Eager to meet the Europeans, the Sioux and the friars travelled back upriver, where they intercepted the five white men not far from the Falls of St. Anthony.

As it turned out, the five white men were coureurs-des-bois led by Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut- a former gendarme, or elite French cavalryman; a veteran of the Franco-Dutch War; and a relative of Henri de Tonti who would become the namesake of Duluth, Minnesota. The previous summer, Du Lhut had, with the blessing of Count Frontenac, travelled to Lake Superior and brokered a peace between the Sioux and the Ojibwa, hoping that such a peace might facilitate the fur trade in the westerly Great Lakes. He also sent some of his men to accompany a Sioux band bound for the Eastern Dakota heartland west of Lake Superior. In the summer of 1680, these scouts had returned with news that a salt lake lay some distance to the west. Like La Salle, Du Lhut had a desire to discover the Northwest Passage and hoped that this ‘salt lake’ constituted an inlet of the Pacific Ocean. When he heard that three white friars were held captive by the Sioux, he and his men set out southwest into the wilderness, hoping to rescue the white men and learn more about this westerly salt lake. Du Lhut convinced the Sioux to release their prisoners and brought Hennepin and his countrymen to Michilimackinac by way of Green Bay. Hennepin proceeded to make the long journey to Montreal, and then to France, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Recovery

Around the time of Hennepin’s capture by the Sioux, after the mutiny at Fort Crevecoeur, Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, formed a new party and returned to the Illinois River. There, he found the Grand Village of the Illinois burnt to the ground. Scattered throughout the ashes were mutilated corpses and poles surmounted by human skulls- unbeknownst to him, the disinterred inhabitants of the village cemetery. To La Salle and his crew, it appeared that an Iroquois war party had wiped out the Illinois village and massacred its inhabitants.

La Salle searched the ruined village for any sign of his faithful lieutenant, Henri de Tonti, but met without success. He and his men then followed the Illinois River towards its confluence with the Mississippi, in which direction it appeared the Iroquois braves had chased the fleeing survivors of the massacre. Along the way, they came across the bodies of the Illinois women and children whom the Iroquois had tortured and partially eaten, but found no sign of Tonti. After nailing a message for his lieutenant to a tree, La Salle and his crew returned to the charred remains of Fort Miami.

In spite of the failure of his most recent expedition, La Salle still hoped to bring the fur trade to the natives who inhabited the waterways south of the Great Lakes. He also realized that such an endeavour would be impossible as long as the Iroquois continued to make incursions into the area, and so he sent out emissaries to the Shawnee tribe for the purpose of forming a defensive anti-Iroquois alliance. La Salle himself led an ambassadorial expedition to the territory of the Illinois Indians. On the way, he became snow blind and was forced to stop. Shortly thereafter, while searching for an herbal remedy to his master’s condition, one of La Salle’s employees encountered a band of Fox Indians who informed him that Henri de Tonti was alive and well, spending the winter with the Pottawatomi Indians of Lake Michigan.

When the spring of 1681 came and La Salle had recovered from his snow blindness, he and his party continued their journey into Illinois territory. There, La Salle met with the survivors of the massacre of the previous year and convinced them to ally themselves with the Miami Indians for mutual protection against the Iroquois. The explorer then proceeded to the proximate territory of the Miami Indians and convinced these natives to ally themselves with the Illinois. Pleased with his success, La Salle travelled to Michilimackinac that May, where he reunited with Tonty and other participants in the misadventure on the Illinois River. Together, La Salle and his men travelled to Fort Frontenac, where they re-outfitted and set out on yet another expedition of discovery.

Journey Down the Mississippi and the Founding of French Louisiana

The French explorer and his party headed all the way to the southern end of Lake Michigan and proceeded down the Chicago River. They made the portage to the Illinois River and followed it to the abandoned remains of the great Illinois village that the Iroquois had destroyed the previous year. They continued on to the Illinois’ confluence with the Mississippi and followed that great waterway southwest. On the evening of their first day on the Mississippi, they reached that river’s junction with the Missouri and set up their camp on the shore nearby. In the days that followed, they paddled past the mouth of the Ohio River, drifted along the shores of a swamp, and glided by a series of promontories known today as the Chickasaw Bluffs. They made their camp in the shadow of the third of these bluffs and set out into the woods in search of game. By evening, all but one of the hunters had returned. Fearing that this man, named Pierre Prudhomme, had been killed by Indians, La Salle had half his men build a makeshift fort atop the bluff and sent the other half into the woods to search for the missing hunter. During their search, the rescue party game upon two Chickasaw Indians upon whom they bestowed presents and messages of peace. Several days later, they came upon a hungry and bedraggled Prudhomme, who had lost his way in the woods. In an effort to console the mortified French-Canadian, La Salle named the new bastion ‘Fort Prudhomme’.

La Salle and his crew continued on down the Mississippi, rowing past swamps and wastelands. On March 13, they found themselves enveloped in thick fog when the throb of a war drum and the war song of Indian braves erupted on one side of the river. The Frenchmen quickly paddled to the opposite shore and constructed a makeshift barricade. The fog soon cleared and the two parties eyed each other from across the river. La Salle beckoned for the Indians to join him and his men on their side of the river, and after some deliberation amongst themselves, a handful of enterprising braves paddled over to the Frenchmen. When La Salle presented them with a peace pipe, the warriors called the rest of the band over and soon the explorers were surrounded by friendly Quapaw Indians.

Throughout the three days that followed their meeting, the Quapaw natives feasted the newcomers, bringing them corn, beans, and dried fruits. At the conclusion of their hospitable reception, La Salle and his men proceeded to the centre of the nearby Quapaw village, where they erected a cross bearing the French coat of arms and claimed the surrounding territory for the King of France.

The explorers then took their leave of their hosts and continued down the river, accompanied by two Quapaw guides. On the way, the encountered and killed several large alligators- animals which none of the Frenchmen had seen before. About 100 miles below the mouth of the Arkansas River, they came to a swamp and a trail which the Quapaw said led to a great Indian village. La Salle tasked Tonti and Zenobius Membre, the latter one of the Recollect friars, with visiting this village while he and the rest of the crew waited by the canoes. The two delegates arrived at the village in two hours and were astonished by what they saw. Instead of the haphazard collection of circular bark wigwams they had expected, Tonti and Membre found a well-laid-out town filled with large square buildings made from mudbricks and rooved with canvas. The explorers paid a visit to the house of the village chief and presented the leader with gifts. The chief, in turn, decided to visit La Salle and his party on the riverbank, where the latter showered more gifts on the former.

The next morning, the explorers encountered another band of Indians further downriver. Although they initially brandished their bows and arrows at the sight of the newcomers, the natives warmed to the explorers when the latter made it clear that they came in peace. “The Sieur de la Salle,” wrote Father Membre in a later reminiscence, “whose very air, engaging manners, tact, and address attract love and respect alike, produced such and effect on these hearts of these people that they did not know how to treat us well enough.” The natives took the explorers to their own village, which greatly resembled the one that Tonti and Membre had just visited.

La Salle and his men voyaged further down the river, passing two more Indian villages, the fearful inhabitants of one of which greeted them with a hail of arrows. Beyond this point, they came across a cluster of wigwams filled with corpses- presumably the product of an enemy raid.

On April 6, the explorers came to a three-pronged fork in the river. He split his company into thirds, assigned each division to a particular branch, and commanded his men to follow their respective waterways to the ocean. The Frenchmen all reached the Gulf of Mexico shortly thereafter and reunited. On the shores of the Atlantic, they erected a cross bearing the words (in French): “Louis the Great, King of France and Navarre, reigns; April 9th, 1682”. La Salle proceeded to give a speech in which he dubbed the watersheds of the Mississippi River and Ohio Rivers “Louisiana” in honour of the French king for whom he then claimed them.

Joseph-Antoine le Febvre, Sieur de La Barre

The purpose of their voyage having been accomplished, La Salle and his crew began the long journey up the Mississippi, subsisting on alligators and surviving a few dangerous encounters with hostile natives. On the way, La Salle contracted some sort of illness and decided to recover at Fort Prudhomme. He tasked his faithful lieutenant, Henri den Tonti, with bringing news of their achievement to Michilimackinac.

La Salle and his men resumed the journey in late July and reunited with Tonti in Michilimacinac in September. There, they learned that La Salle’s great supporter, Count Frontenac, had been recalled to France for unlawfully imprisoning his deputy’s teenaged son. Frontenac had been succeeded as Governor of New France by Joseph-Antoine le Febvre, Sieur de La Barre, a French Naval officer and former colonial administrator whose service in Europe, French Guyana, and the Caribbean had been coloured by both stunning victories and displays of incompetence and cowardice. The explorers also learned that the Iroquois were planning to conduct another offensive against the Miami Indians. La Salle knew that he would need to prevent the outbreak of war if he ever hoped to bring the fur trade to Louisiana, and so he set out with his crew for the unfinished ruins of Fort St. Louis at Starved Rock, on the Illinois River. The explorers reached the site without incident and constructed the wooden palisaded Fort St. Louis throughout December, 1682.

Throughout that winter and the spring of 1683, La Salle and his men maintained their somewhat-shaky relationship with the Illinois and Miami Indians, through whom they learned that the rumoured Iroquois offensive was imminent. Accordingly, La Salle sent several of his men back to the

French settlements along the St. Lawrence to secure ammunition and other supplies necessary for the French explorers to defend themselves and their allies. Unfortunately, these men were detained as unlicensed coureurs des bois by agents of Governor La Barre who, unbeknownst to La Salle, hoped to supplant Frontenac’s virtual monopoly of the fur trade with his own. La Salle refused to leave Fort Saint Louis to deal with the situation in person, fearing that if the Iroquois attacked the local natives in his absence, his Illinois and Miami friends might think that he was behind the attack. Instead, he sent letters to La Barre in which he asked the Governor to release his men and allow them to bring back ammunition and reinforcements.

Instead of complying with La Salle’s request, La Barre seized all of La Salle’s assets, including Fort Frontenac, which he claimed was undermanned. Realizing now that the Governor was determined to destroy his enterprise, La Salle waited out the summer at Fort St. Louis before travelling back to Quebec with the intention of sailing for France and obtaining support from the King. On the way, he met a French military officer named Louis-Henri de Baugy, whom La Barre had sent to seize Fort Saint Louis. Subduing his anger, La Salle sent a letter to Tonti instructing him to comply with the officer’s directive before he himself continued on to France.

A New Venture

La Salle boarded the ship Saint-Honore and sailed across the Atlantic to the city of La Rochelle. From there, he travelled to the Palace of Versailles, where he was approached by an old acquaintance, an abbot named Claude Bernou, who invited him to take part in a dangerous scheme he had contrived.

Prior to his departure, La Salle had learned that La Barre and his enemies in New France had already informed the king of his voyage down the Mississippi and had done their best to portray it in a negative light. Their efforts apparently succeeded, as the king, in a letter to La Barre, dismissed La Salle’s voyage of discovery as “utterly useless”, and ordered the delighted Governor to prevent similar expeditions in the future. Although he suspected he would have little luck convincing the king to sanction his endeavours on the Mississippi on the merit of his discoveries alone, he had resolved to try anyways.

Abbe Claude Bernou suggested that La Salle abandon his original plan and marry his ambition with a more promising enterprise which he had already set into motion. Earlier that year, Louis XIV had invaded the western frontier of the Holy Roman Empire, where he hoped to construct a series of fortresses for the purpose of strengthening France’s eastern border. The Holy Roman Empire and its close ally, Spain, retaliated by engaging France in what is known today as the War of the Reunions. Since France was now at war with Spain, Bernou had suggested to a courtier named Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, that the French Army establish a base at the mouth of a New World river known today as the Rio Grande, from which it could launch an invasion into New Spain and capture its rich silver mines. When La Salle arrived in France, Bernou suggested that the explorer increase the odds of his own success while simultaneously adding weight to the abbot’s proposal by suggesting to the Court that the aforementioned military base be built near the mouth of the Mississippi instead of that of the Rio Grande and recommending himself as the leader of the invasion of New Spanish territory. In order to convince the Court that the Mississippi would make a suitable staging point for the invasion of New Spain, La Salle would have to allow Bernou to doctor his account of his voyage so that the geography of the lower Mississippi seemed more accordant with that of the Rio Grande. He would also need to create a map of the Mississippi which showed a tributary of that river, known today as the Red River, lying closer to Spanish territory than La Salle had reason to believe it did. Despite its inherent dangers, La Salle agreed to the abbot’s proposal, drawing an erroneous map of the Mississippi and allowing Bernou to edit his account of his voyage. Armed with these fraudulent documents, La Salle presented his case to the Marquis de Seignelay.

La Salle convinced the courtier of the merit of his proposal and, through him, received royal permission to oversee the new province of Louisiana. More than that, King Louis XIV restored La Salle’s appropriated assets and gave the explorer 100 soldiers, eight officers, a 36-cannon warship, a cargo vessel, and two smaller ships, along with orders to seize Spanish possessions up the Rio Grande.

The Siege of Fort Saint Louis

Meanwhile, at Fort Saint Louis on the Illinois River, La Salle’s old crew had emerged from a rather harmonious winter, considering the circumstances. In accordance with La Salle’s orders, Henri de Tonti had received La Barre’s agent, Louis-Henri de Baugy, with courtesy. Despite his pleasant reception, Baugy spent the winter of 1683/84 attempting to convince Tonti’s men to abandon the fort and work for La Barre. His efforts were for naught; the explorers remained faithful to their employer.

On March 12, 1684, the Frenchmen were besieged by 200 Iroquois warriors who took up residence outside the fort’s palisaded walls. After spending six days holed up in the fort, the defenders were relieved by a party of Illinois braves who drove the Iroquois away.

The Voyage to Texas

Back in France, La Salle prepared to embark on what would be his final trans-Atlantic voyage. On July 24, 1684, the explorer and his men, accompanied by several Recollect missionaries, including La Salle’s own brother and nephew, and a number of unmarried girls who were to populate the Louisiana colony, set sail for the New World.

Rather than ingratiate himself with his new men, La Salle incurred the resentment of many of his subordinates on the voyage across the Atlantic. Due to a dearth of space, La Salle’s men were forced to sleep exposed to the elements on the decks of their ships. Ignoring the advice of his second-in-command, a French Royal Navy Captain named Taneguy Le Gallois de Beaujeu, La Salle refused to stop for water at the island of Madeira. When his sailors, following the Gulf Stream, reached the Tropic of Cancer, they prepared to ‘baptize’ newcomers to the tropics in the maritime fashion of the day, namely by lowering them over the side of the boat in a pulley-drawn bucket and dunking them thrice into the sea. Initiates could escape this rite of passage by paying the crew in coin or liquor. La Salle refused to allow his sailors to extort his crew in this way, much to their irritation.

By the time they reached the Caribbean, La Salle and much of his crew had come down with some sort of illness. Most of the crew stopped at the town of Port-de-Paix, located on Saint-Domingue (the French portion of Hispaniola; present-day Haiti) across La Tortue Channel from Tortuga Island. In defiance of La Salle’s orders, Captain Beaujeu, who had grown to despise La Salle, decided to anchor in the harbour of Petit-Goave, a town located on the southerly Tiburon Peninsula. On the way, Beaujeu lost one of his smaller boats, filled with munitions and provisions, to Spanish privateers.

The would-be colonists spent the next few months resting in port. Some recovered from their illnesses while others succumbed to theirs. The Frenchmen, La Salle among them, finally resumed their journey in November, sailing past the island of Cuba and into the Gulf of Mexico. The explorers unwittingly sailed west past the mouth of the Mississippi River. La Salle, who was in command of the fastest ship in his tiny fleet, sailed his vessel along the coast in search of the river. He reunited with the rest of his crew off the coast of Matagorda Island, located about 400 miles west of the Mississippi and 150 miles north of the mouth of the Rio Grande. Beaujeu accused the explorer of deserting him, while La Salle accused the captain of neglecting to follow him.

While La Salle and Beaujeu proceeded to argue over whether or not to return to France emptyhanded, some of their crew members, who had been sent to explore the nearby shore on foot, were captured by a band of Indians. La Salle set out to rescue the Indians, prompting the crew of one of his three remaining ships to sail after him into Matagorda Bay and fatally crash into a reef. After overtaking the Indians and convincing them to release his men, La Salle ordered his crew to unload the cargo from the foundering ship. Many supplies were lost during this operation. To make matters worse, the Frenchmen were subsequently attacked by the Indians whom they had recently encountered. Two men were killed in the ambush, while another two were wounded.

This was too much for Beaujeu. After taking on several Frenchmen who decided to desert La Salle, the Navy captain set sail for France, leaving the explorer and his much-reduced crew to fend for themselves.

The French Colony in Texas

La Salle and his remaining men and women constructed a hasty fort from the remains of their sunken ship. That accomplished, they spent their days hunting, fishing, and exploring the surrounding area, always on the lookout for roving Indians and Spanish sails. Over the next few months, two men deserted, another was hanged for attempting to desert, and an officer was fatally bitten by a snake.

La Salle became convinced, during the course of his local explorations, that the Mississippi must lie somewhere to the east. Before setting out in search of that easterly waterway, he had his men construct a more permanent fort on the shores of the Lavaca River, which empties into Matagorda Bay. The explorers spent the summer of 1685 executing this task under the harsh direction of La Salle, having to haul timber from a forest about three and a half miles away under the sweltering Texan sun. Thirty men died during this process from illness and heatstroke.

On November 1st, La Salle and a company of explorers headed east, leaving a sizeable crew behind to man the fort. They were accompanied by the crew of their last remaining vessel, the Belle, which followed them along the coast. During the course of their journey, the explorers encountered a number of native bands, some of whom they were compelled to scare away with their firearms. Members of one of the bands with which they met told them about the Spaniards who patrolled the coast, and claimed that they were universally hated by all the tribes in the area. The company finally reached the shores of some river, which some of the crew members thought might be the Mississippi. There, they build a fort of wooden palisades.

When the fort was complete, La Salle and his men retraced their steps to the fort on the Lavaca River. During the return journey, six of La Salle’s men were killed in a skirmish with the natives. Shortly thereafter, the Belle and her crew mysteriously disappeared.

On April 22nd, 1686, La Salle set out for the distant realm of New France, where he hoped to secure provisions and equipment for his colonists. Accompanied by a party of twenty, which included his brother and nephew, he hiked to the fort that his men had recently constructed on the shores of that mysterious river to the west. There, he found the five surviving crew members of the Belle, who told him that the ship had wrecked on a sand bar.

The explorers proceeded northeast over the prairies, fording five rivers and encountering several bands of natives, one of which attempted to ambush them in the night, and another of which sold them five horses. On the way, La Salle lost twelve of his men, most of them to desertion and one of them to an alligator. Shortly after reaching what is known today as the Neches River, the weary explorers decided to return to the fort on the Lavaca, having failed their Herculean mission.

The Assassination of La Salle

The colonists spent a cheerless winter at the fort. On the feast of Epiphany, 1687, La Salle and a company of explorers set out on yet another impossibly long expedition to Canada. The Frenchmen followed their previous trail northeast, crossing prairies and rivers and supplementing their meagre diet with fresh buffalo they killed along the way.

When they reached the end of their previous trail, La Salle ordered a company of his men to search for a cache of dried vegetables they had buried the previous year. Although the contents of the cache proved to have spoiled, the foragers managed to kill several buffalo on their way back to the main camp and proceeded to process the meat. Several of the hunters decided to keep some choice cuts of meat and fat for themselves, as was their right. However, when La Salle’s nephew, Moranget, who had left the main party to search for them, found the hunters and learned of their appropriations, he flew into a rage and confiscated all the meat.

To the weary explorers who had endured months of privation, malnutrition, and hard labour with little reward for their efforts, Moranget’s actions were unforgiveable. One of the hunters, named Pierre Duhaut, convinced four of his companions to help him murder Moranget. In order to get away with their crime, they would also need to kill two of their companions who were loyal to La Salle, and so they agreed to murder those men as well. That night, when the three victims had completed their watch and were fast asleep, Duhaut and his conspirators rose from their blankets and dispatched the hapless trio with an axe.

When the grisly work was done, the murders decided that they ought to assassinate La Salle himself, as much in order to prevent their future recrimination as to gratify the hatred they had developed towards the leader of their sorry expedition.

When his nephew, Moranget, failed to return to the main camp after two days, La Salle went to look for him. He was accompanied by a Recollect friar named Anastase Douay and two Indians. According to the friar in a later reminiscence, La Salle, throughout the course of their excursion, “spoke to me of nothing but matters of piety, grace, and predestination; enlarging on the debt he owed to God, who had saved him from so many perils during more than twenty years of travel in America. Suddenly, I saw him overwhelmed with a profound sadness, for which he himself could not account. He was so much moved that I scarcely knew him.”

The small party soon came to a small river above which La Salle spied two large birds flying in a circle, as if attracted by the scent of blood and decay. The explorer then fired two pistols in the air in order to attract his missing men. The shots were heard by Duhaut and company, who were on the other side of the river. The conspirators stealthily crossed the stream and made their way through the long grass towards the hapless explorer, muskets in hand.

One of the conspirators, a fifteen-year-old servant of Duhaut named Jean l’Archeveque, emerged from concealment and presented himself to La Salle. The explorer asked the young man where Moranget was, and l’Archeveque replied, in an insolent tone, that he was somewhere downriver. Furious at the teenager’s lack of respect, La Salle made his way towards l’Archeveque. Suddenly, two shots rang out from the tall grass and 43-year-old Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle fell dead with a musket ball in his head.

The murderers then called out to the terrified friar, Douay, that he had nothing to fear and approached the body of their former captain. After mocking La Salle’s corpse, they stripped it naked and dragged it into the brush.

The words of one of La Salle’s loyal followers, Henri Joutel, who wrote about his experience in Texas in a later reminiscence, constitute an appropriate epitaph for the fallen explorer:

“His firmness, his courage, his great knowledge of the arts and sciences, which made him equal to every undertaking, and his untiring energy, which enabled him to surmount every obstacle, would have won at least a glorious success for his grand enterprise, had not all his fine qualities been counterbalanced by a haughtiness of manner which often made him insupportable, and by a harshness towards those under his command, which drew upon him an implacable hatred, and was at last the cause of his death.”

Aftermath

After disposing of La Salle’s body, Duhaut and the rest of the conspirators, accompanied by Douay, rejoined the main party and informed them of their deed. Duhaut claimed authority over the tiny company and decided not to kill La Salle’s brother and others who had been loyal to the explorer.

The Frenchmen then paid a visit to a nearby Indian village in order to purchase supplies. There, the conspirators quarreled amongst themselves over whether to return to the fort on the Lavaca or head up the Mississippi to Canada. The argument devolved into a brutal shootout which left Pierre Duhaut and another of the conspirators dead.

Following their falling out, one of the remaining Frenchmen stayed with the Indians while the remainder made the long journey up the Mississippi and Illinois to Fort Saint Louis, losing one of their number along the way to drowning. There, they reunited with Henri de Tonti and his men, who had been fighting the Iroquois, with whom New France was again at war. Strangely, the explorers neglected to inform Tonti and his men of La Salle’s fate. They continued up the Illinois to the Great Lakes and New France beyond, keeping La Salle’s assassination a secret until they reached the Court of King Louis XIV in France.

Henri de Tonti finally learned of La Salle’s death in September 1687. Indignant, the Italian explorer decided that it was his duty to bring his commander’s murderers to justice, rescue the colonists on the Lavaca River, and perhaps carry out La Salle’s planned invasion of Spanish possessions on the Rio Grande. He left Fort St. Louis with five Frenchmen and a handful of Indians, but was forced to abandon the mission due to a string of mishaps which occurred along the way.

Back on the Lavaca River, the sorry remnants of La Salle’s colony were decimated by an outbreak of smallpox. Most of the survivors were subsequently killed by Indian warriors, and the remainder where captured by Spaniards shortly thereafter. Thus perished the final enterprise of Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, the great French explorer who founded French Louisiana.

Sources

- The Discovery of the Great West (1869), by Francis Parkman

- Exploration of the Great Lakes: 1669-1670, Francois Dollier de Casson and Rene Brehan de Galinee

- The Fighting Governor: A Chronicle of Fronenac (1915), by Charles William Colby

- Cavelier de la Salle, Rene-Robert (1966), by Celine Dupre in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Volume I

- Dollier de Casson, Francois (1969), by Jacques Mathieu in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Volume II

- Brehant de Galinee, Rene de (1966), by Olivier Maurault in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Volume I

Leave a Reply