The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 7

Continued from The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 6.

The Massacre of Fort Michilimackinac

Alexander Henry spent the spring of 1763 at Sault Ste. Marie, during which time he assisted the resident soldiers in producing maple syrup. He returned to Michilimackinac on May 20th, accompanied by a travelling English gentleman named Sir Robert Dovers. In addition to the British soldiers who had taken up residence there two years prior, he found the fort occupied by a number of French fur traders who had travelled there from different parts of the Great Lakes.

At that time, there was a rumour floating around the fort that the local Ojibwa Indians planned to launch an attack on the garrison and kill all the Englishmen therein. About four hundred of these natives were camped around the fort, and although they appeared perfectly friendly when they brought in their furs to trade, Henry warned the fort’s commander not to trust them.

On June 3rd, Henry was visited by his Ojibwa blood brother, Wawatam, who seemed uncharacteristically depressed. The chief told Henry that he was sorry to see him at Michilimackinac, and expressed his hope that his adopted brother would accompany him to Sault Ste. Marie. Although he never explicitly said as much, the chief implied that something evil was about to befall the fort, and hinted that the Ojibwa camped nearby would have a hand in it. Henry thanked his adopted brother for the information but informed him that he would not leave the fort until he had concluded some unfinished business.

“I had made…” wrote Henry, “so much progress in the language in which Wawatam addressed me as to be able to hold an ordinary conversation in it; but the Indian manner of speech is so extravagantly figurative that it is only for a very perfect master to follow and comprehend it entirely.” Unfortunately, Henry had not sufficiently mastered the language at that time and failed to interpret Wawatam’s message as a dire warning to leave at the earliest opportunity. When the chief realized that he would not persuade Henry to leave the fort, he departed with visibly low spirits.

Ominously, Henry spent the rest of the day selling tomahawks to Ojibwa warriors and, at their request, showing the braves an inventory of the items he had for sale.

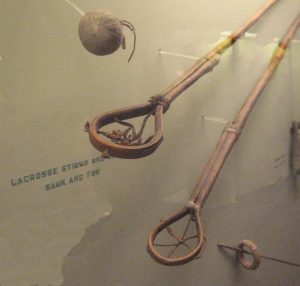

The following day was June 4th, the birthday of King George III. In honour of the great English chief, the local Ojibwa warriors decided to play a game of lacrosse against a neighbouring band of the Sauk Nation. The Ojibwa declared that the game would be played outside the fort’s walls, and invited the resident Englishmen to watch it.

Many of the English soldiers, including Major George Etherington, who commanded the garrison, accepted the Ojibwa’s offer and filed out of the fort to watch the game, leaving their weapons inside. Alexander Henry, on the other hand, used the opportunity to write letters to distant friends.

Unbeknownst to the hapless English soldiers who lounged in the field outside the fort as the game commenced, the Ojibwa had concocted a brilliant plan to capture the fort by surprise. While the soldiers were distracted by the Indian athletics, a handful of Ojibwa women inconspicuously made their way towards the fort’s open gates, concealing bundles of tomahawks and scalping knives beneath the blankets they wore around their shoulders. When the women were in place, one of the native athletes lobbed the lacrosse ball over the fort’s walls, ostensibly in an effort to keep it from falling into the hands of his Sauk opponents. The Ojibwa athletes subsequently raced into the fort, where they seized the weapons that the women had smuggled inside.

While he sat composing in his cabin, Henry heard a cacophony of Indian war cries erupt outside. “Going instantly to my window,” he wrote, “I saw a crowd of Indians within the fort furiously cutting down and scalping every Englishman they found.” Henry seized a flintlock shotgun and contemplated stepping outside to help his fellow countrymen, some of whom were being scalped alive before his eyes. To do so, he quickly realized, would be suicidal. With little thought now but to hide and wait out the storm, Henry frantically scanned the surrounding courtyard for refuge. His eyes fell on a handful of French-Canadian fur traders who calmly watched the slaughter unfold from the safety of their cabins, apparently secure in the knowledge that the Indians would not harm them.

Henry snuck out the back door of his cabin and jumped the fence that separated his residence from that of his neighbour, a French-Canadian trader named Langlade. He peered through Langlade’s back door and saw that the trader’s whole family had gathered by the window to watch the massacre unfold. He called out to the Frenchman and asked if he could hide in his home. Langlade shrugged his shoulders, indicating that he was powerless to help the Englishman, before turning back to the window.

Fortunately, Henry’s entreaty attracted the attention of a Pawnee Indian slave woman who served in the Langlade household. Without her master’s knowledge, the servant beckoned for Henry to follow her and guided him to a tiny attic in the Langlade cabin. Once the Englishman was safely inside, the Pawnee locked the door behind him and took away the key.

Through a crack in the wall, Henry watched the Ojibwa warriors go about their grisly work. “The dead were scalped and mangled,” he wrote, “the dying were writhing and shrieking under the unsatiated knife and tomahawk; and from the bodies of some, ripped open, their butchers were drinking the blood, scooped up in the hollow of joined hands and quaffed amid shouts of rage and victory.”

When the slaughter was complete, a number of bloodstained Ojibwa braves entered the Langlade home. The warriors asked the fur trader whether any Englishmen were hiding in his house, to which Langlade replied that they were welcome to search the place to their satisfaction. The warriors immediately pulled on the door to the attic and found it locked. His heart hammering in his chest, Henry crawled to the corner of the room and covered himself with birch bark baskets sticky with maple sap.

No sooner had the Englishmen concealed himself than the attic door was unlocked. “An instant after,” Henry wrote, “four Indians entered the room, all armed with tomahawks, and all besmeared with blood upon every part of their bodies. The die appeared to be cast. I could scarcely breathe; but I thought that the throbbing of my heart occasioned a noise loud enough to betray me. The Indians walked in every direction about the garret, and one of them approached me so closely that at a particular moment, had he put forth his hand, he must have touched me.” Somehow the Indians failed to find the Englishman, shrouded as he was by the darkness, and eventually left the attic, leaving Henry “with sensations not to be expressed.”

Exhausted from fear, Henry crawled over to a feather bed nearby and collapsed into a deep sleep. He was discovered the following day by Langlade’s wife, who agreed to keep his presence a secret.

The next day, a party of Ojibwa warriors, all of them roaring drunk, stormed into the Langlade home and informed the fur trader that Henry’s body had not been accounted for, and that they suspected that either Langlade or another French-Canadian fur trader was hiding him. His wife, speaking in French, which the Indians did not understand, implored her husband to give up Henry, of whose presence she had previously informed him despite her promise to the Englishman, so that their children would not suffer retribution in the event that the Indians discovered him themselves. Langlade acquiesced and led the Indians to the attic, delivering Henry into their hands.

Henry was captured by a warrior named Wenniway, who, after some contemplation, decided to adopt him as his brother rather than kill him on the spot. After surviving a murder attempt by an Indian who owed him a trading debt, Henry was brought to a cabin in which the Ojibwa chiefs had lodged Major George Etherington and two other high-ranking officers, these prisoners having been spared the slaughter in the hope that they could be ransomed. There, Henry learned that the Ojibwa had killed seventy Englishmen and imprisoned about twenty.

Continued in The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 8.

Leave a Reply