The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 8

Continued from The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 7.

A Prisoner of the Ojibwa

The following day, the Ojibwa warriors loaded Henry and his fellow prisoners into canoes, handed them paddles, and commanded them to head for the southwesterly Beaver Island, the largest island in Lake Michigan. Each canoe contained seven Indians and four prisoners.

Due to heavy fog, the Ojibwa hugged the western shores of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and stopped at an Ottawa village. There, a hundred Ottawa warriors stole the prisoners for themselves, angry that that the Ojibwa had massacred the English without having consulted them first. The Ottawa loaded Henry and the prisoners into their own canoes and brought them back to Michilimackinac.

The following day, the Ottawa and the Ojibwa held a council to discuss the fate of the English prisoners. During this time, Henry learned that a great Ottawa chief named Pontiac had recently sparked an Indian rebellion against the occupying British throughout the so-called Pays d’en Haut, or “Upper Country”- the Great Lakes region. Insulted by the haughty demeanour of and the trading restrictions imposed by the English officers who had recently taken up residence in the old French forts throughout the region, a combined war party of Ottawa, Ojibwa, Potawatomi, and Huron Indians had launched an attack against the English-occupied Fort Detroit, situated on the river which connects Lake Erie with Lake Huron. Although the Indians had been unable to penetrate the fort itself, they succeeded in slaughtering or capturing every English man, woman, and child whom they found outside its walls. They proceeded to take Forts Sandusky, St. Joseph, Miami, and Ouiatenon, all of them situated on the shores of the Great Lakes. Michilimackinac was the fifth British fort to fall in what would become known as Pontiac’s War.

The Ottawa returned the English prisoners to the Ojibwa in exchange for some of the spoils they acquired from their raid on Michilimackinac, telling them that the Ojibwa planned to eat them. Henry and his fellow captives were taken by canoe to a nearby Ojibwa village. On the way, their captors offered them slices of bread which they cut with knives still stained with the blood of the soldiers they had slaughtered. “The blood they moistened with spittle,” wrote Henry, “and rubbing it on the bread offered this for food to their prisoners, telling them to eat the blood of their countrymen.”

When they reached their destination, the prisoners were confined in a longhouse, each of them tied by their necks to a pole. Henry, hungry and shivering from the cold, spent a sleepless night pondering his fate.

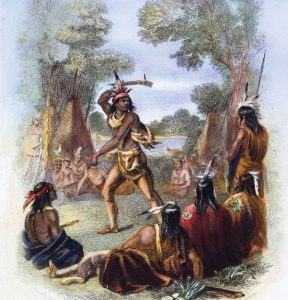

The next day, the entire war party held a council which the prisoners were forced to attend. In the midst of this meeting, Henry’s self-appointed Ojibwa brother, Wawatam, entered the council lodge and made a speech in which he implored the head war chief- a warrior named Menehwehna- to release Henry into his custody. After Wawatam presented him with gifts, the chief acquiesced. Henry was released from his bonds and brought to Wawatam’s wigwam, where he enjoyed his first solid meal since the massacre.

Wawatam’s intervention likely saved Henry’s life. On the morning following his release, an Ojibwa chief who was absent at the time of the massacre arrived in camp and slaughtered seven of the English prisoners in order to show his support for his countrymen’s actions. The Indians dismembered the fattest of these prisoners, cooked his corpse in five kettles outside the lodge in which the prisoners were housed, and devoured him.

Shortly thereafter, the Ojibwa transported their prisoners to the Mackinac Island in Lake Huron, fearful of an English counterattack and believing that the island would be easier to defend than their village. Prior to their journey, they threw a live dog into Lake Michigan as a sacrifice to the spirit whom they believe controlled the weather on the Great Lakes.

“As we approached the island,” Henry wrote, “two women in the canoe in which I was began to utter melancholy and hideous cries. Precarious as my condition still remained I experienced some sensations of alarm from these dismal sounds, of which I could not then discover the occasion. Subsequently I learned that it is customary for the women on passing near the burial places of relations never to omit the practice of which I was now a witness, and by which they intend to denote their grief.”

Skull Cave

After spending several days on the island, the Ojibwa captured a couple of inbound English canoes laden with trade goods, among which were several casks of rum. Fearful that his friend might be murdered that night in the inevitable drunken carousal, Wawatam brought Henry to a small, dark cave on the island’s central heights and instructed him to wait therein until his return.

Henry made a bed of spruce boughs in the middle of the cave, wrapped himself in a blanket, and went to sleep. He was awakened the following morning by some protrusion beneath him, which had begun to press uncomfortably into his body. The offending object proved to be a bone, which Henry assumed must be that of a deer or some other animal which some bygone predator had dragged into the cave to eat. “But when daylight visited my chamber,” Henry wrote, “I discovered with some feelings of horror that I was lying on nothing less than a heap of human bones and skulls which covered all the floor!”

Wawatam returned to the cave two days later, having finally recovered from the night of revelry. Henry showed him the bones, of which Wawatam professed to have had no prior knowledge. The friends speculated that the cave must have been used as a sort of charnel house by Indians centuries ago.

Continued in The Adventures of Alexander Henry the Elder: Part 9.

Leave a Reply