The Ouija Board of Cobden, Ontario

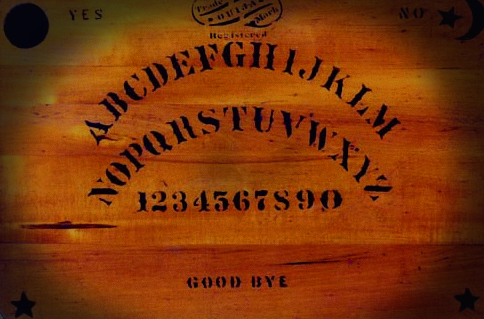

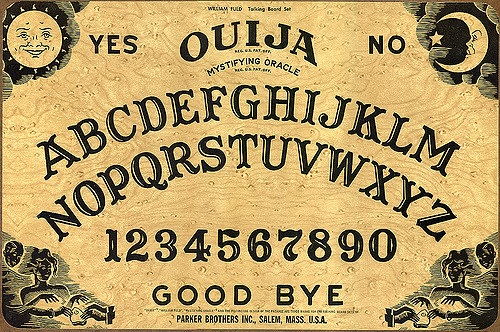

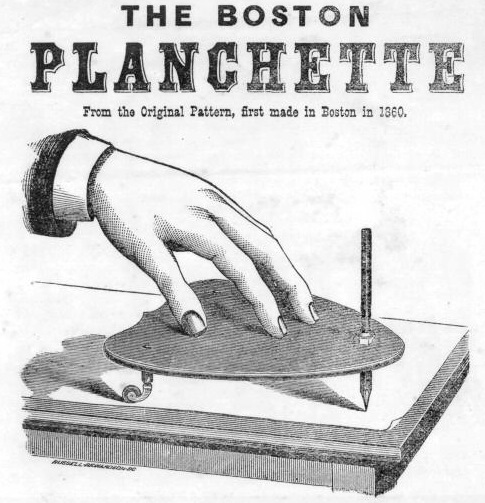

Since at least the late 1800s, Western spiritualists have attempted to communicate with the spirits of the dead through so-called ‘talking boards’. These devices originally consisted of wooden boards on which were painted the letters of the alphabet, along with an essential accessory called a ‘planchette’- a heart-shaped piece of wood with three wheels or felt sliders attached to its underside. During Victorian-era séances, occult practitioners would dim the lights, sit around the talking board, and invite any spirits present to communicate with them. That accomplished, the practitioners would lightly place their fingers on top of the planchette, which would proceed to glide across the surface of the talking board, seemingly of its own accord. Ideally, the planchette would point to a succession of letters which spelled out a coherent message ostensibly attributable to some otherworldly entity.

In the 1890s, four American businessman patented a particular style of talking board which displayed the alphabet, the numbers 0 through 9, and the words ‘YES’, ‘NO’, and ‘GOOD BYE’. The businessman dubbed their innovation the ‘Ouija board’, and went on to found the Kenneth Novelty Company, through which they produced and sold these devices on a massive scale. Due to their marketing efforts, the Ouija board quickly metamorphosed from a relatively obscure spiritualist tool into an innocent and extremely popular parlour game. This perception endured until 1973, when the horror film The Exorcist hit American theatres, transforming the talking board once again into a sinister apparatus of the occult.

Although most post-1973 accounts of Ouija board use are either tales of scoffing skepticism or dire dissuasion, there are a few pre-Exorcist anecdotes involving positive outcomes resultant of Ouija board consultation. One of these appeared in the February 1955 issue of the magazine Fate.

Violet Bender of Ottawa, Ontario, the lady who submitted the story, claimed that sometime in the 1880s, her aunt . had come into the possession of a talking board. Although Mrs. Bender was not explicit in her description of the apparatus, it seems possible that this particular talking board’s planchette was equipped with a pencil.

Violet’s aunt used the apparatus to help her compose music. In 1902, her aunt died, and the board was bequeathed to her mother, the wife of an Anglican clergyman.

Violet’s eldest sister, Winnifred, who was eighteen years old at the time, quickly discovered that the board would write for her. “It provided her with many hours of amusement,” Violet wrote. “Her girl friends came to ask about their beaux. It replied equally well to mental questions- that is, to unspoken questions in a person’s mind. Whoever had the strongest will or the greatest power of concentration got the reply to his or her question.”

At that time, Violet and her family lived in the village of Cobden, Ontario, situated on an old and well-used portage route circumventing a set of rapids on the Ottawa River. Word quickly spread throughout Cobden, as it so often does in small communities, that Winnifred could locate lost or stolen articles using her Ouija board.

Early one morning, Violet and her family awoke to the frantic ringing of the rectory bell; someone, it seemed, desperately wanted to see the minister. Violet’s father threw open the rectory window and stuck out his head. “Who is there?” he called. “What do you want?”

“We want to ask that board of your daughter’s a question,” came the reply.

“Well,” the minister said with some reproach, “four o’clock in the morning is a queer time to come to ask a question.”

The visitor replied that his little girl was lost in the woods, and that a search party had been hunting for her all night, but to no avail.

Violet’s father told the man that he would do what he could. He roused Winnifred, informed her of the situation, and asked her to use her talking board to determine the girl’s location. Afraid of what the answer might be, Winnifred asked the question and put her hands on the planchette. The board gave the following reply:

“THE CHILD IS SAFE IN A HOUSE NEAR THE TRACK”

Winnifred’s father relayed the information to the desperate father, who tore off in the direction of the railroad.

Later that day, the father found his little girl safe and sound in a log cabin near the railway. She had wandered away from her family’s farm with some cows, and the family living in the cabin had taken her in.

Thirty years later, Violet Bender was happily married to a clergyman and living not far from Cobden. One evening, she got a call from another clergyman who asked whether she had the talking board and planchette that her family once owned. Violet informed the minister that her eldest sister, Winnifred, had the board, and that she was now married and living in Australia.

“The clergyman,” Violet wrote, “then explained that a child was lost in that district, and the people, remembering how over 30 years ago another lost child had been found, wanted to consult the planchette again.”

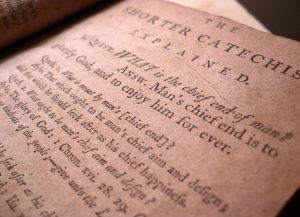

Rather than end on this note, the author of this piece feels obliged to remind you, dear reader, that this particular anecdote, with its semi-happy ending, is a bit of an anomaly when it comes to Ouija board stories. Today, popular culture is riddled with cautionary tales expounding the dangers of Ouija board séances, most of them warning that improper use of the device can leave the practitioner vulnerable to attacks by evil spirits or demons. These exhortations are based on the tenets of various Judeo-Christian religious denominations which condemn any attempt to contact the spirit world. Perhaps the most well-known religious denunciation of Ouija board use is that of the Roman Catholic Church, which expounds its position in paragraph 2,116 of the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church:

“All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to ‘unveil’ the future.”

“All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to ‘unveil’ the future.”

The section outlining this doctrine cites two verses from sacred scripture. The first of these is Chapter 18, Verse 10 of the Book of Deuteronomy (the fifth book of the Hebrew Torah, detailing the divine laws revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai), which denounces child sacrifice, fortune telling, soothsaying, divining, spell-casting, consulting ghosts and spirits, or seeking “oracles from the dead”. The second passage cited is Chapter 29, Verse 8, of the Book of Jeremiah, which warns against false prophets and diviners who lie and deceive in God’s name.

Whether you consider the Ouija board a useful tool, a harmless toy, or a dangerous door to another world, perhaps the wisest policy is to treat it with caution.

Source

“The Lost Child”, by Violet Bender of Ottawa, Ontario, in the February 1955 issue of the magazine Fate, courtesy of American Fortean researcher Gary S. Mangiacopra

Leave a Reply