Legends of Cobourg’s Victoria Hall

If you drive fifty minutes south from Peterborough, Ontario, you’ll come to the lively little town of Cobourg. Despite its relatively small size (or perhaps because of it), this Canadian town on the northern shores of Lake Ontario has an exceptionally vibrant community, the members of which seem to take enormous pride in its heritage. According to resident John Draper, “life in Cobourg is as near ideal as it can be. The town is small enough to be friendly and free of city problems yet large enough to have great entertainment and cultural activities as well as good stores.”

The crowning jewel of this quaint Ontario town is Victoria Hall, an impressive heritage building which dominates King Street, situated as it is two blocks north of Cobourg’s historic harbour. This 19th Century monument is home to a number of intriguing legends, including a rumour of an illicit Royal affair and two chilling ghost stories.

The Story of Victoria Hall

In order to set the stage for the legends of Victoria Hall, a little backstory is required.

The Rise of Cobourg, Ontario

The town of Cobourg, Ontario, in which our legends take place, was first founded in the wake of the American Revolution by United Empire Loyalists– American expatriates loyal to the British Crown. Due to its favourable location on Lake Ontario, Cobourg quickly grew into an important regional milling and manufacturing centre, its population bolstered by an influx of poor but hard-working Irish settlers.

By the mid-1800’s, many Cobourg residents believed that their town was destined to become one of Upper Canada’s most important cities. Their optimism was fuelled by the Grand Trunk Railway’s plan to build its mainline, which would connect Toronto with Montreal, through the town. In order to cement Cobourg’s fate as one of Upper Canada’s most prominent cities, the town’s citizens decided to build their own railway- the Cobourg and Peterborough Railroad- north to the town of Peterborough, transforming Cobourg into a regional transportation hub.

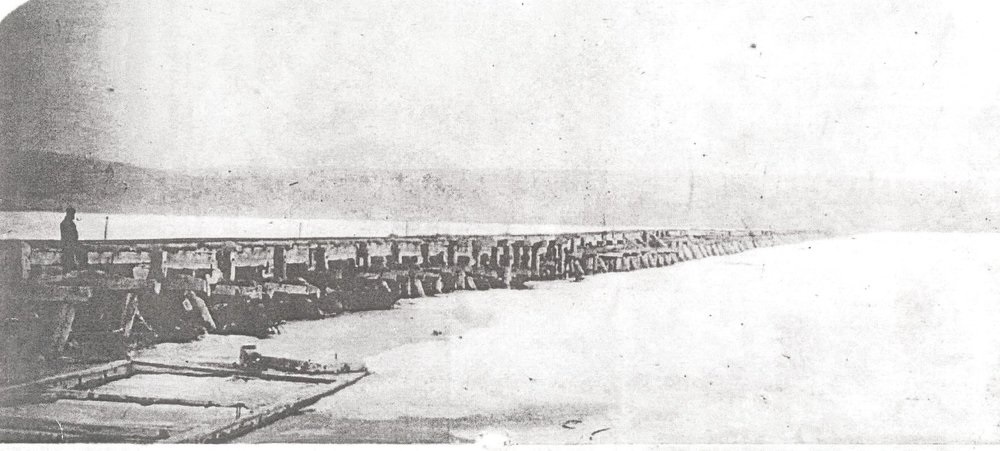

The Cobourg Peterborough Railroad

The Cobourg and Peterborough Railroad was completed on December 29, 1854, at significant cost to many of the townspeople. In an effort to compete with their neighbouring rival, the westerly town of Port Hope, the town council of Cobourg had insisted that the railway be built across Rice Lake- a long, three-mile-wide body of water that stood between Cobourg and Peterborough- rather than around it. To do otherwise would be to concede Port Hope’s geographic superiority, as a railway circumventing the lake would be much longer than a railroad from Port Hope to Peterborough, which would naturally skirt the lake’s western shores. As a result, the railwaymen had constructed a massive, three-mile-long wooden bridge across the lake- one of the most impressive engineering feats in North America at the time, and the largest contemporary trestle bridge in the world.

On New Years’ Day, 1855- three days after the railroad’s grand opening to the public- the bridge across Rice Lake shifted, its wooden supports unable to withstand the force of the expanding lake ice. The structure was quickly straightened, and for the next two years, underwent constant repairs as the train it supported routinely serviced the citizens of Cobourg.

The Construction of Victoria Hall

In 1856, when it seemed fairly certain that the railway was there to stay, Cobourg’s town council hired celebrated Toronto architect Kivas Tully (after he won a design competition they held) to design a grand civic building worthy of Cobourg’s status as Ontario’s next great metropolis.

By the early autumn of 1860, Tully’s creation was complete. On Cobourg’s King Street, not far from the waterfront, stood an enormous architectural masterpiece built of pale yellow brick and elaborately-carved sandstone. This 700,000-square-foot, three-story, E-shaped landmark was built in the Palladian fashion (“Palladian” being a style inspired by the designs of 16th century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio, who was, in turn, inspired by Classical Greek and Roman architecture), complete with Corinthian columns, a Greco-Roman roof, and an orator’s balcony, and capped with an impressive clock tower. The ornamental sandstone framing the entrance bore carvings of the Tudor rose, the Scottish thistle, and the Irish shamrock, reflecting Upper Canada’s British heritage.

The splendour of the building’s interior matched that of its elegant exterior. Its courtroom was modelled after London’s historic “Old Bailey”, the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales. Its meeting rooms and offices were similarly ornate. Its ballroom was exquisite, constructed in Baroque fashion. And its crowning glory, its 1000-seat Concert Hall, was hand painted in trompe-l’oeil style.

This magnificent building was named “Victoria Hall” in honour of Great Britain’s reigning monarch, Queen Victoria.

Victoria Hall’s Grand Opening

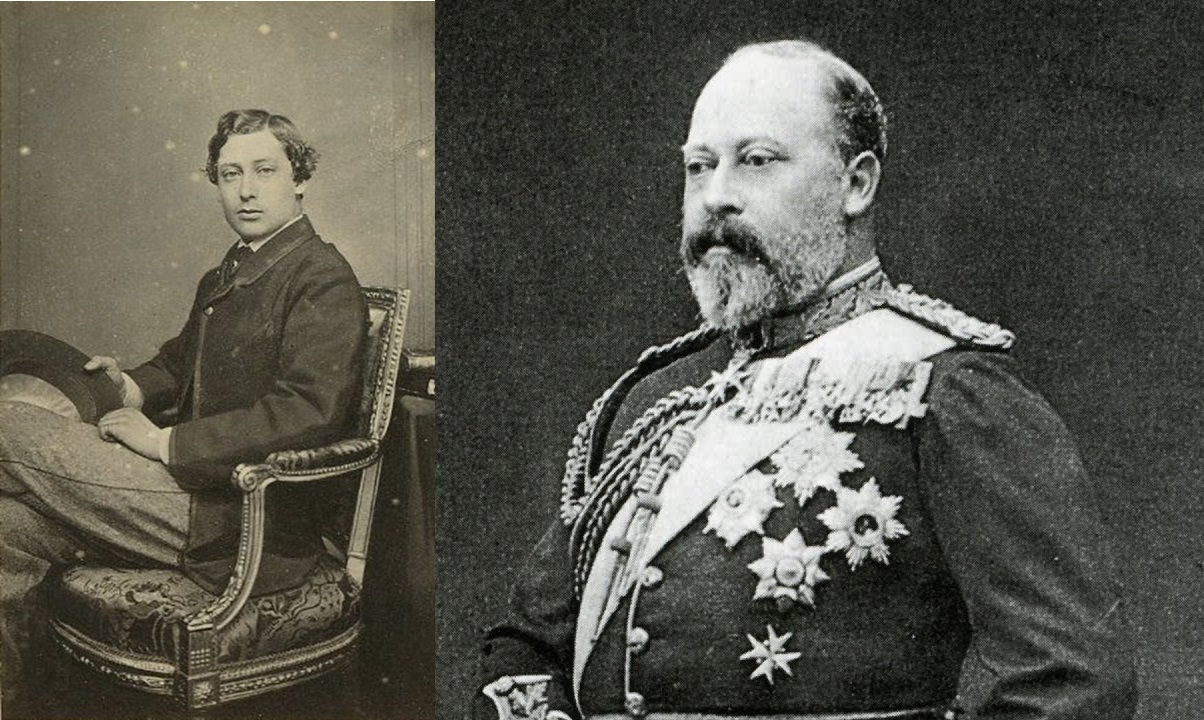

At the time of Victoria Hall’s completion, Queen Victoria’s 19-year-old son, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (Great Britain’s future King Edward VII), was undertaking the very first Royal tour of Canada- a tradition which endures to this day. To the townspeople’s delight, it was announced that Prince Edward would visit Cobourg during his tour and take part in the grand opening of the opulent town hall which had been named in honour of his mother.

On September 7, 1860, Prince Edward and his retinue arrived at Cobourg Harbour by steamer. Accompanied by an honour guard of Upper Canada’s Volunteer Militia Rifles, he travelled by carriage to Victoria Hall. After delivering a formal address, the Prince of Wales opened the grand ball, and by 11 o’clock that night, the teenage Prince was dancing with the gleeful ladies of Cobourg.

A Royal Affair

According to legend, one particularly attractive Cobourg lady named Mrs. Parks caught the eye of Prince Edward in Victoria Hall’s ballroom that evening. Whatever happened between the young aristocratic and Canadian lady that night is a matter of pure conjecture. Roughly nine months later, however, Mrs. Parks gave birth to her son, Archie, who is said to have grown up to bear a remarkable resemblance to King George V, the son and successor of King Edward VII. To make this tale even more intriguing, legend has it that Archie would come into the Cobourg bank once a month to deposit sizeable cheques from the British Treasury.

The Prince’s Departure

The day following Victoria Hall’s first grand ball, Prince Edward was invited to travel to Peterborough, the next destination on his tour, via the newly-constructed Cobourg and Peterborough Railway. The Prince accepted the invitation, and in no time the journey was underway.

At about halfway between Cobourg and Peterborough, the train reached Rice Lake and its infamous wooden bridge. At this point, Prince Edward and his retinue exited the train and announced that they were going to travel across the lake via steamboat instead of by rail (a steamer had regularly ferried passengers across the lake since the 1840’s, when a rough plank road connected Cobourg with Rice Lake). Although the Prince’s aides claimed that water travel would afford Prince Edward a better view of the lake’s scenery, the mortified townspeople suspected that the decision was prompted by a lack of confidence in the bridge’s structural integrity.

The Collapse of the Rice Lake Bridge

Whatever the case, history shows that any potential misgivings about the solidity of the bridge over Rice Lake might not have been entirely unfounded.

Shortly before Prince Edward’s visit, the men of the Cobourg Peterborough Railroad were approached by a mysterious businessman who advised that they allow him to lease their railway to the larger Grand Trunk Railroad. Believing this to be a profitable venture, the railwaymen agreed.

Unbeknownst to the men of the Cobourg Peterborough Railroad, this businessman was, in fact, an agent of their arch rival, a burgeoning railway company from Port Hope. Instead of leasing the railroad to the Grand Trunk, the businessman sold it to the Port Hope railwaymen, who subsequently had their employees sabotage it by removing its iron bolts and fittings for use in their own railroad. Shortly thereafter, the middle section of the bridge over Rice Lake collapsed. The structure was never rebuilt, and Cobourg has remained a small Ontario town with an uncharacteristically grandiose town hall ever since.

The Courtroom Ghost

Despite the tragedy surrounding its genesis, the citizens of Cobourg, Ontario, have put Victoria Hall to excellent use. Its celebrated Concert Hall has staged countless plays, shows, speeches, and musical productions over the years. It has seen many a local church fundraiser and political rally. During the Fenian raids of the 1860’s and ‘70’s, it served as an armoury for the first and second Companies of the 40th Northumberland Battalion, and during the first two World Wars, it housed the workshop of the Cobourg Branch of the Red Cross.

In addition to these aberrant functions, Victoria Hall, for many years, served as the town hall it was originally meant to be. It held the municipal and county administrative offices of Cobourg and Northumberland, respectively, as well as several law offices and Masonic lodge rooms. And for many years, its sunken courtroom served as the arena for countless legal disputes and witnessed the trials of Northumberland County’s criminally accused.

According to legend, sometime in the 1870’s, a defendant condemned to some unenviable fate leapt from the prisoner box in the courtroom of Victoria Hall and ran down the aisle to the front doors in a last-ditch escape attempt. To his dismay, he found that the doors were locked. He shook them desperately, with all his might, but could not get them to open.

Legend has it that, on quiet summer nights, those same doors rattle violently, shaken by the shade of that unfortunate prisoner who remains unable to escape the courtroom of Victoria Hall, even in death.

The Restoration of Victoria Hall

In 1970, a hundred and ten years after its grand opening, cracks were discovered in the walls of Victoria Hall. The structure, it seemed, had shifted, much like its 19th Century counterpart, the ill-fated bridge over Rice Lake. The following year, Victoria Hall- a National Historic Site since 1959- was vacated, having been declared structurally unsafe.

As the town was unable to afford repairs, a motion was made for the building’s demolition. The motion was denied by a single opposing vote cast by Cobourg’s Deputy Reeve, a lady named Lenah Field Fisher.

Instead of allowing the magnificent building to fall into decay, Lenah Fisher founded the Society for the Restoration of Victoria Hall. Throughout the 1970’s, she and other Society members carried out a fundraising campaign with the aim of restoring the historic building to its former glory.

The campaign was ultimately successful, and Victoria Hall was officially reopened in 1983. Unfortunately, Lenah Field Fisher was unable to enjoy the fruits of her labour; she passed away in 1980, posthumously donating her money and her estate to the cause.

Some say that the spirit of Lenah Fisher returned to witness Victoria Hall’s grand reopening. During one of the speeches in the opening ceremony, a ball globe light fixture exploded immediately after her name was said. If Lenah Fisher truly paid a visit to Victoria Hall in spirit that day, a number of first-hand accounts reported by performers and staff seem to suggest that she may have never left.

The Green Lady of Victoria Hall

Since the early 1980’s, both regulars and visitors have reported seeing the apparition of a woman wandering the corridors of Victoria Hall, only to vanish before their eyes. Most often, this mysterious spectre is seen wearing a green velvet dress, earning her the nickname the ‘Green Lady’.

Victoria Hall’s Concert Hall is said to be the Green Lady’s favourite haunt. One performer named Jamie Hunt once watched the hem of a woman’s dress disappear through a backstage wall at the exact spot at which the door to the caretaker’s quarters once stood. Hunt’s future wife, Beth, who now works as the Concert Hall facilitator, once observed the taps in the backstage washroom turning on and off by themselves during the middle of a performance. Production and tech crews have opened up the Concert Hall’s control booth to find the lighting and soundboard levels mysteriously tampered with, and performers have reported seeing a mysterious lady in green watching them during rehearsals.

Some suspect that this spectre might be the ghost of Lenah Fisher, returned from the grave to walk the halls of the historic building she fought so hard to preserve.

Sources

- “Victoria Hall, Cobourg, Restored: With Tales of Illicit Affairs and Ghosts that go Bump on the Door”, by Terry Boyle, in the October 1977 issue of the monthly newspaper magazine Early Canadian Life, courtesy of Fortean researcher Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- “Cobourg Peterborough Railway”, by Colin Caldwell, on CobourgHistory.ca

- “Living in Cobourg,” by John Draper, on CobourgInternet.com

- “Cobourg’s Victoria Hall Home to the ‘Green Lady’: Ghost Sightings Common During Theatre Productions”, by Karen Longwell, October 18, 2013, on NorthumberlandNews.com

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Leave a Reply