3 Canadian Mad Scientists- 3: Welsford Parker

Back to 3 Canadian Mad Scientists.

Welsford Parker and the Mineral Wave Ray

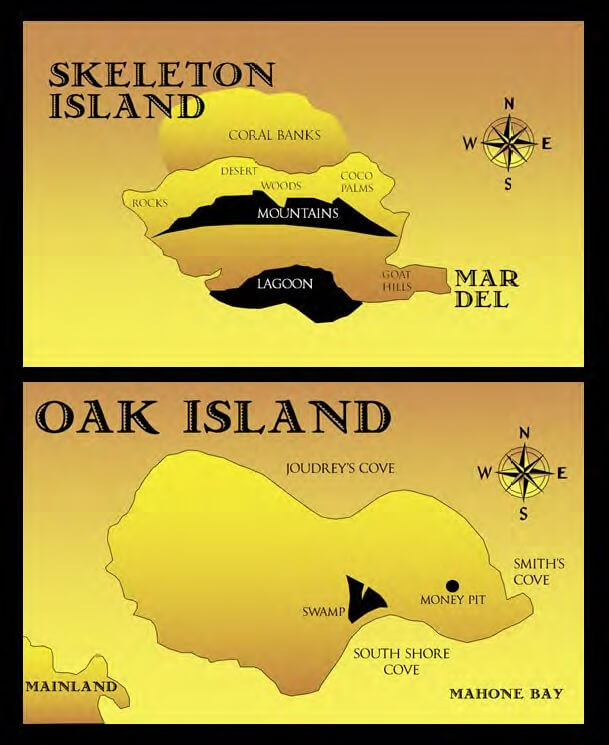

If you drive an hour southwest of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the Fishermen’s Memorial Highway, across the Chebucto and Aspotogan Peninsulas and down the Atlantic Coast, you’ll come to the picturesque little community of Western Shore. Just east of this hamlet, in the waters of Mahone Bay, lies a tiny forested isle known as Oak Island, the site of Canada’s longest-running treasure hunt.

In 1795, so the legend goes, three locals discovered a strange depression in the soil on the island’s eastern end. Subsequent investigation revealed the depression to be the top of a deep backfilled shaft in which platforms of oak logs rested at regular 10-foot intervals. Knowing that Mahone Bay, in centuries past, had served as a haven for privateers, the locals suspected that the pit might be the depository of pirate loot.

Ever since this tantalizing discovery of what has since been dubbed the ‘Money Pit’, treasure hunters from all over Canada and the United States have tried their hands at retrieving the shaft’s mysterious contents, only to be thwarted by what appear to be brilliantly-engineered underground flood traps, catastrophic subterranean collapses, and uncannily disproportionate bad luck. To date, Oak Island’s elusive treasure remains undiscovered.

Over the past two centuries, exasperated treasure hunters, unable to solve the riddle of Money Pit through conventional methods, have resorted to all manner of unorthodox solutions in their efforts to locate the island’s slippery spendables. Dowsing rods, automatic writing, psychics, and séances have all been employed by desperate searchers for whom the finest modern technology failed to deliver. Of all these bizarre recourses, by far the most exotic were those taken by Oak Island treasure hunter Gilbert Hedden throughout the year 1937.

The Wilkins Map

Gilbert Hedden was a wealthy New Jersey-based steel manufacturer who took up the Oak Island treasure hunt in 1934. Blessed with a mechanical mind and educated in engineering, Hedden considered himself equal to the task of unlocking Oak Island’s secrets. After three frustrating years of spinning his wheels, however, the hard-headed American was ready to take any help he could get.

In 1937, Hedden’s lawyer, Reginald V. Harris, read a recently-published book written by British journalist Harold T. Wilkins entitled Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island. The first twelve chapters of this book describe the life of Captain William Kidd, a 17th Century Scottish privateer who was hanged for piracy in 1701, and the aftermath of his execution. The next seven chapters detail various hunts for Kidd’s supposed treasure, which the privateer is rumoured to have buried on some deserted isle sometime prior to his arrest in 1698, and which some theorists have suggested lies beneath Oak Island. The final chapters of Wilkins’ book reveal a new break in the case: the discovery of four 17th Century treasure maps said to have once belonged to Captain Kidd.

These treasure maps, Wilkins claimed, were recently discovered by a wealthy Englishman named Hubert Palmer, who collected genuine pirate artifacts as a hobby. Throughout the 1930s, Palmer acquired four pieces of 17th Century furniture bearing engravings which indicated that they once belonged to William Kidd. Within each of these artifacts was a secret compartment, and within each compartment was a treasure map depicting a particular island in the South China Sea.

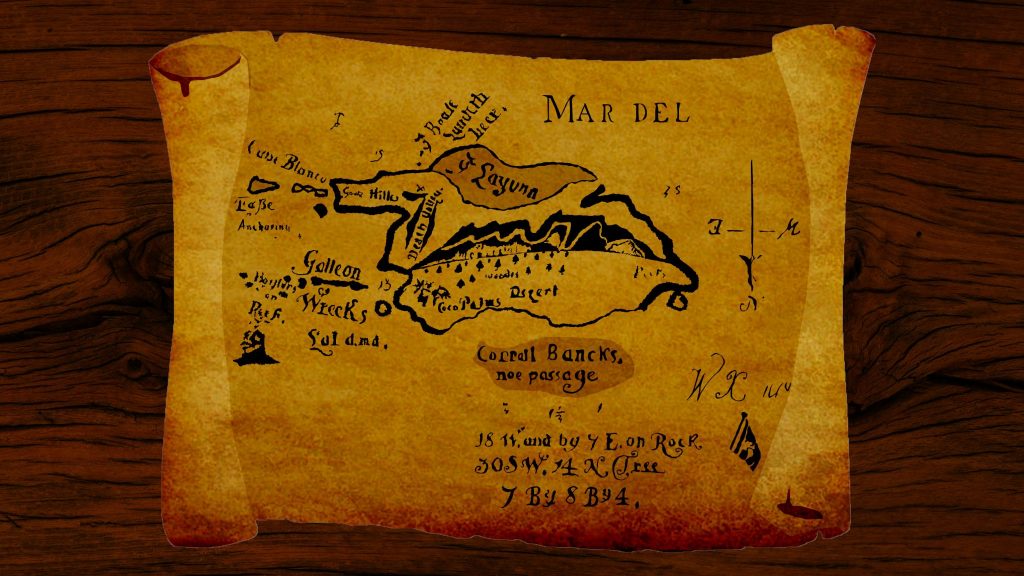

At the end of his book, Wilkins included a number of photographs featuring the four pieces of antique furniture, Kidd’s letter of marque, and various portraits of the notorious 17th Century pirate. Hidden among these photographs is an image of a hand-drawn treasure map with a reversed compass, which an accompanying description denotes the first chart that Palmer discovered in Captain Kidd’s supposed sea chest. The map included a host of landmarks and a cryptic legend consisting of three lines of directions.

Reginald Harris couldn’t help but notice that this treasure map, when flipped right-side up, bore remarkable resemblance to Oak Island. Even more intriguing was the fact that many of the map’s features corresponded with landmarks on Oak Island. The lawyer showed the map to Gilbert Hedden, who was similarly fascinated by its many resemblances to his own treasure island. Hedden had a hunch that Wilkins’ chart might, in fact, be a real Oak Island treasure map drawn up by the original Money Pit builders, and sent a letter to Harold Wilkins in which he voiced his suspicion.

Wilkins sent a letter back to Hedden assuring him that the treasure map in his book was not a map of Oak Island, but rather a depiction of an island in some ‘eastern sea’ far from the Atlantic. Hedden was unconvinced. To him, the similarities between Wilkins’ map and Oak Island were too strong to be coincidental. He then turned his attention towards the mysterious directions at the bottom of the chart.

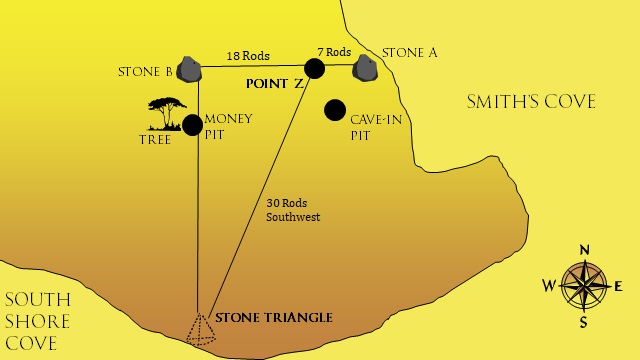

Incredibly, upon closer investigation, Hedden found that the map’s directions and most of its landmarks corresponded almost perfectly, in both quality and dimension, with various features on Oak Island, the existence of many of which the treasure hunter had previously been unaware. Despite the author’s assertions to the contrary, Hedden was more convinced than ever that the chart in Wilkins’ book was a genuine Oak Island treasure map.

Determined to follow this new and exciting lead, Hedden decided to travel to England and meet Harold Wilkins in person. When Hedden informed the writer of his intentions, Wilkins wrote back that he was willing to meet with the treasure hunter, but that such a journey would be a waste of time, as the map in his book was definitely not an Oak Island treasure map. Nevertheless, Hedden made the trip to England and met with Wilkins in December, 1937, in his London hotel room outside Green Park, Piccadilly. His experience was both strange and discouraging.

Upon meeting Hedden, the English author confessed that the map in his book was, in fact, a diagram of his own devising. His publisher had demanded that he include some sort of authentic-looking treasure map in his book. Hubert Palmer, the owner of the four Captain Kidd maps which Wilkins described in his book, would not allow him to publish photos of the charts, and so Wilkins had no choice but to draw his own treasure map based upon his recollection of Palmer’s maps. When his publishers further stipulated that his map contain instructions on how to locate the treasure for added spice, Wilkins fabricated the three lines of directions using nothing more than his imagination.

Baffled, Hedden told the journalist about the uncanny connection between Wilkins’ ad-libbed treasure hunting instructions and the many landmarks on Oak Island. As the treasure hunter explained the extraordinary coincidence, Wilkins became convinced that he must be the reincarnation of a 17th Century pirate, perhaps even Captain Kidd himself, and that his subconscious mind had conjured up some long-forgotten memory of the map leading to Kidd’s lost treasure, buried on Oak Island. After Wilkins enthusiastically revealed his conviction to Hedden, the latter began to suspect that the journalist was, in his words, “every bit as crazy as his book would make him seem.”

Within material furnished him by Fortean archivist Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra, the author of this piece discovered a puzzling sequel to this mystifying saga, which he presented in a YouTube video entitled Another Wrinkle in the Wilkins Map in the summer of 2019.

The Parker Machine

Harold Wilkins’ treasure map constitutes but one of three curious means by which Gilbert Hedden attempted to solve the riddle of Oak Island in 1937. That same year, the New Jerseyite consulted a psychic from Saginaw, Michigan, named John Wicks, who had previously told the aforementioned Frederick Blair that the Money Pit was the repository of the lost treasure of Tumbez, Peru, spirited away by Incan priests during the 16th Century Conquista of Francisco Pizarro. Instead of shedding light on the location of Oak Island’s treasure, as Hedden hoped he would, Wicks simply told the treasure hunter that “the time [was] not yet ripe” for the lost gold of the Incas to be found.

Hedden’s third 1937 recourse was the ‘Mineral Wave Ray’, a piece of ‘black box’ technology with mysterious inner workings invented by Welsford R. Parker, an equally-mysterious engineer from Windsor, Nova Scotia. Parker claimed that his camera-equipped machine took photographs of objects on which it was able to pinpoint the location of hidden gold and other previous minerals. Although Hedden was dubious of the machine’s ability, his lawyer, Reginald Harris, convinced him to give it a chance, claiming that a fellow lawyer vouched for its efficacy after witnessing a demonstration of the machine in his law office. Hedden allowed Parker to use the machine on Oak Island, and, after an unsuccessful test, wrote it off as “a complete and not very clever hoax”.

Gilbert Hedden abandoned the Oak Island treasure hunt in 1938, passing the torch to a New York engineering professor named Erwin Hamilton. Hamilton, in turn, was succeeded by a Nova Scotian businessman named Mel Chappell, who had worked with his father on the island in the late 1800s.

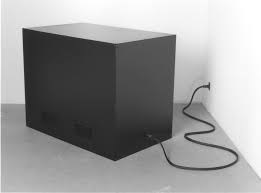

In December 1950, twelve years after the ‘Mineral Wave Ray’s’ first appearance on Oak Island, Welsford Parker, who had since relocated to Belleville, Ontario, convinced Mel Chappell to allow him to test a new and improved iteration of his machine on the island. This device consisted of a black box filled with wires, vacuum tubes, condensers, resistors, and batteries, with a camera lens attached to one end. It contained two receptacles, one of which was to hold a sample of the substance sought (ex. gold, silver, etc.), and the other being a narrow slit into which a photograph of the target area was to be slipped. The device was surmounted by a pair of rods which the operator was to hold. When the device approached an accumulation of the desired mineral, the rods were allegedly drawn in its direction.

At Chappell’s invitation, Parker wandered about the island with his machine, locating five different spots at which his device indicated the presence of buried treasure. It cost Chappell $35,000 to excavate these points of interest, none of which contained the promised loot. “I fell for it,” Chappell conceded in a later reminiscence. “It looked possible to me at the time, but it turned out there was nothing to it.”

Four years after Parker’s second Oak Island failure, the inventor’s mysterious machine came to the attention of John W. Campbell, the editor of the science fiction magazine Astounding. Campbell was an early (and perhaps the only true) champion of ‘psionics’- a hypothetical field of study revolving around the development of electronic machinery through which the practical application of psychic powers can be effected.

In the spring of 1954, Campbell met with Welsford Parker at the inventor’s home in Bellevue. After examining Parker’s Mineral Wave Ray and listening to Parker’s explanation of its mechanism, the editor became convinced of its merit. “Parker is not a fool,” he wrote. “He’s a brilliant pragmatic experimenter. He has stumbled onto a new, basic principle of the universe.” This principal, Campbell theorized, was an “urge field” to which all human beings were connected. The Mineral Wave Ray, he believed, allowed its operator to unconsciously, psychically locate the object of his or her desire.

Campbell suspected that Parker’s machine could be used as a substitute for radio once identical devices were manufactured. Convinced of its commercial potential, he purchased ten thousand shares of stock in the inventor’s company, Parker Universal Contract Ltd. Following his investment, he optimistically wrote his sister, “[A] larger-size crackpot has to be a millionaire to be a genius, and I’ll be a millionaire.”

Unfortunately for Campbell, Welsford Parker proved an uncooperative business partner. During his second trip to Belleville, Campbell pushed the inventor to define the terms of their arrangement, to which Parker responded by terminating their partnership. As one writer put it, “It evidently never occurred to Campbell… that a man who could spend decades working on such a device might not be the sort to work well with others…” Regrettably, Campbell remained a “crackpot” by his own definition, failing to attain the financial success which he hoped would bolster his legitimacy as a proponent of psionics. Similarly, Welsford Parker’s mysterious machine failed to live up to its own hype, condemning its inventor to the shadowy status of the mad scientist.

Leave a Reply