Rapids of the Dead: A Canadian Horror Story

The history of North America is peppered with tales of severe hardship which throw into stark relief both the noblest and the basest characteristics of human nature. Some of these are stories of extraordinary perseverance and heroic self-sacrifice; testaments to the human capacity for virtue in the face of insurmountable odds. Others are bone-chilling tragedies, in which the crushing weight of adversity drove men and women to commit acts of unspeakable depravity.

The Donner Party

One of the most famous horror stories to come out of the American Old West is the tale of the Donner Party, a group of eighty-seven pioneers from the Midwestern United States who attempted to reach California by wagon train in 1847. After committing themselves to what they thought was a shortcut across Utah’s Great Salt Lake Desert, they headed into the Sierra Nevada Mountains just as winter began to set in. Hemmed in on all sides by impassable snow, they found themselves trapped in that rugged country, and were forced to spend the winter in a handful of abandoned cabins.

The pioneers quickly exhausted their food supplies and began to go hungry. After devouring the last of their oxen, they resorted to eating leather and any mice they could trap in their cabins. When those meager substitutes were depleted, members of the Donner Party began to starve to death. Left with no other choice but to follow their companions to the grave, a handful of desperate survivors began to feed upon the only nourishment available to them: the flesh of the dead.

When members of a rescue party reached the Donner Party camps later that winter, they met with a nightmarish scene which appalled even their hardened frontier sensibilities. Working off the notes of a survivor who had escaped to civilization and returned with the rescuers, reporter J.H. Merryman described the ghoulish display which confronted the Californians in an article in the December 9th, 1847 issue of the Illinois Journal:

“Among the cabins lay the fleshless bones and half-eaten bodies of the victims of the famine. There lay the limbs, the skulls, and the hair of the poor beings who had died from want, and whose flesh preserved the lives of their surviving comrades, who, shivering beneath their filthy rags, and surrounded by the remains of their unholy feast, looked more like demons than human beings. They had fallen from their highest state, though compelled by the fell hand of dire necessity.”

In the end, only forty-eight of the eighty-seven members of the Donner Party returned from the mountains, many of them having survived by resorting to cannibalism.

The Dalles Des Morts

It might surprise some Canadians to learn that the same period of Canadian history has a very similar horror story of its own. Though precisely as gruesome as the tale of the Donner Party, this chilling piece of Canadian history is all but forgotten, preserved only in contemporary writings and a handful of history books.

This story takes place at the western end of the Canadian Rockies near the city of Revelstoke, British Columbia, on the Columbia River at what is now the Lake Revelstoke Reservoir. Before the Revelstoke Dam was built in the late 1970s, the Columbia upriver from Revelstoke shot through a narrow canyon, forming what French-Canadian voyageurs of the 19th Century dubbed the Dalles des Morts, or the Rapids of the Dead.

The Tragedy of 1838

This sinister-sounding landmark owes its name to two grisly disasters to which it was party in the early 1800s. The second and less horrific of the two occurred in 1838, when a great English fur trading syndicate called the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) controlled the watershed of the Columbia River. Every year, the HBC transported trade goods, supplies, and mail down the Columbia in the final leg of a huge annual shipment across the continent called the Columbia Express. It was during the 1838 Express run that the tragedy in question took place. In his 1858 travel memoir Travels and Adventures Among the Indians of North America, Irish-Canadian painter Paul Kane, who travelled with the 1846 Columbia Express for the purpose of sketching the Canadian frontier, summarized the story as it was told to him by a veteran voyageur who played a major role in the event.

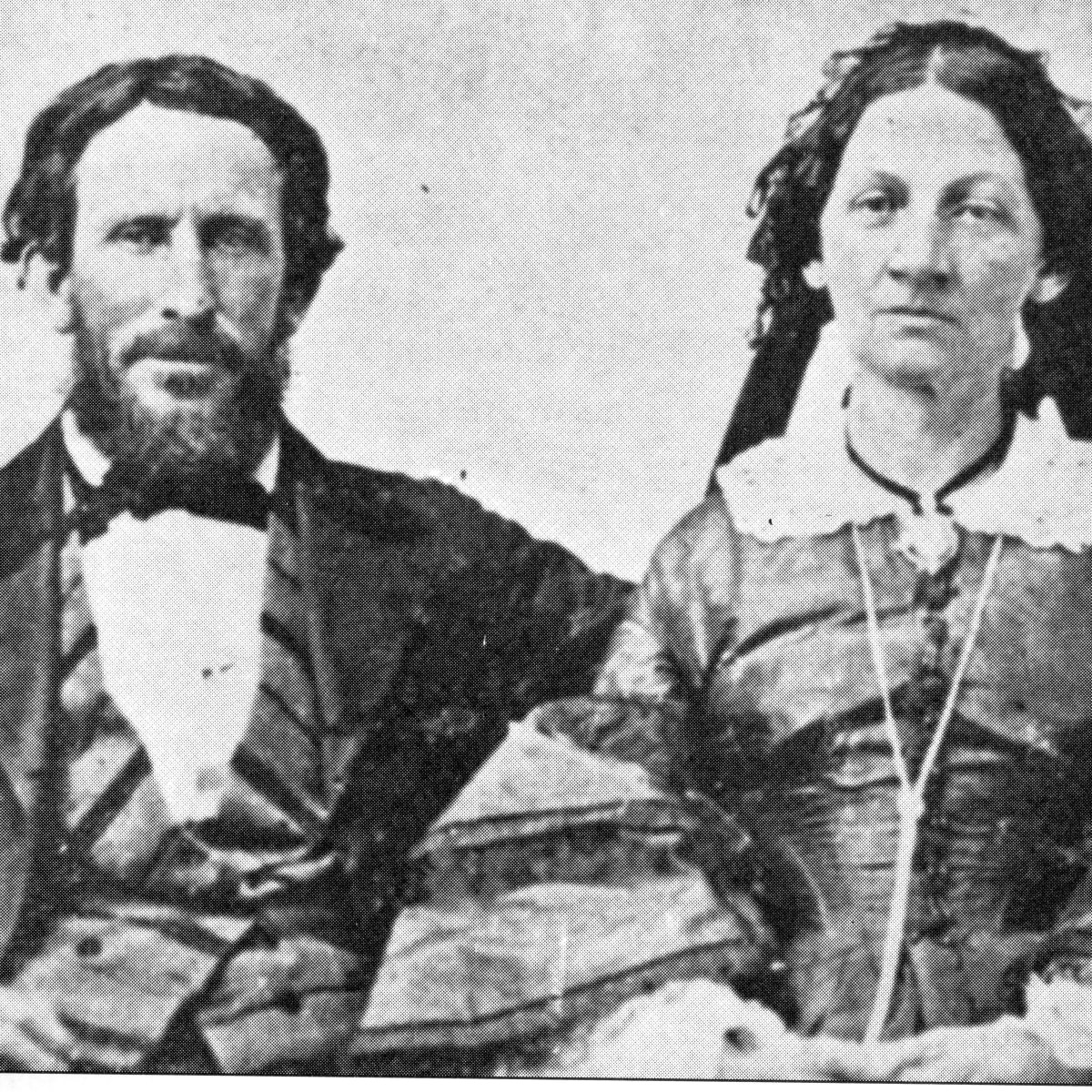

That year, Kane’s informant had served as a steersman in the Columbia Express. Among the forty travellers who accompanied him on this trans-continental journey were his ten-year-old daughter, a young Company man named McGillveray and his dog, a young botanist, and a half-breed girl with whom the botanist fell in love. Historian Jean Murray Cole, in a 2001 commentary on the event, identified the botanist as an Englishman named Robert Wallace; the “half-breed girl” as Maria Simpson, the Metis daughter of HBC Governor Sir George Simpson; and, indirectly, Kane’s informant as a French-Canadian pilot named Andre Chalifoux.

“A mutual attachment induced [the botanist and the Metis girl] to become man and wife, at Edmonton,” the voyageur told Kane, “though few couples, I think, in the world would choose a trip across the mountains for a honeymoon excursion; but they bore all their hardships and labours cheerfully, perfectly happy in helping each other, and being kind to their companions.”

The party arrived at the head of the Dalles des Morts on October 22nd, 1838. As the rapids’ whirlpools appeared to be “throwing out and not filling”, they decided to run the watercourse. “I therefore went on without stopping,” Kane’s informant told him, “and when in the midst of the rapids, where there was no possibility of staying the downward course of the boat, I discovered to my dismay that the whirlpools were filling. One moment more and the water curled over the sides of the boat, immediately filing her. I called out for all to sit still and hold on steadily to the seats, as the boat would not sink entirely owing to the nature of the cargo, and that I could guide them to shore in this state. We ran more than a mile in safety, when the boat ran close by a ledge of rocks. The botanist, who held his wife in his arms, seeing the boat approach so near the rock, made a sudden spring for the shore; but the boat filled with water, yielded to the double weight of himself and wife, and they sank clasped in each other’s arms. The boat suddenly turned completely bottom upwards; but I and another man succeeded in getting on the top of her, and were thus carried down safely. We thought we heard some noise inside the boat, and the man who was with me, being a good swimmer, dived under, and soon, to my unexpected joy, appeared with my little daughter, who almost miraculously had been preserved by being jammed in amongst the luggage, and supported by the small quantity of air which had been caught by the boat when she turned over. We soon got ashore: M’Gillveray and four others saved themselves by swimming, the remaining fourteen were drowned; we immediately commenced searching for the bodies, and soon recovered all of them, the unfortunate botanist and his wife still fast locked in each other’s arms- an embrace which we had not the hearts to unclasp, but buried them as we found them, in one grave. We afterwards found M’Gillveray’s little dog thrown up dead on a sandbank, with his master’s cap held firmly between his teeth.”

The Cannibalism of 1817

The first and more grisly of the two disasters for which the Rapids of the Dead were named took place in 1817, when the HBC’s chief rival, the North West Company (NWC), ruled the watershed of the Columbia. According to the story which Paul Kane learned from his voyeur companions, a French-Canadian, a Metis, and an Iroquois, fearful of running the rapids, attempted to lower their canoe down it with tracklines, the ends of which they held from the shore. Their efforts were in vain; the trio lost their canoe and all of their provisions in the frothing white waters. Left with no other choice, the party continued on foot, picking their way along the rocky slopes of the riverbank.

Three days after the disaster, the Metis abandoned his companions, fearing that they might kill him and eat him. His fears were justified; that night, the Iroquois clubbed the French-Canadian to death with a stick. After gorging himself on the corpse, the native proceeded to cut the remainder of the man’s flesh into strips, which he dried on the rocks of the riverbank. That accomplished, the Iroquois continued on to the foot of the rapids, where he built a raft and proceeded downriver with his dried meat, which he covered with a piece of pine bark.

Shortly thereafter, he was intercepted by a North-West Company rescue party which had been sent to search for him and his companions. The Iroquois hastily attempted to dispose of the evidence of his crime, using his foot to push away his raft and its ghastly contents while he entered the canoe of his rescuers. Suspicious of the Iroquois’ anxiety to throw away what appeared to be perfectly good provisions, one of the engages overtook the raft, lifted the bark, and discovered, amidst strips of dried meat, a severed human foot. Pretending not to notice anything amiss, he inconspicuously slipped the appendage into a bag, determined to present it to his superior at the earliest opportunity. Despite his best efforts, this action was perceived by the Iroquois.

The party continued on to Spokane House, a North-West Company trading post situated on the Spokane River. One night during the voyage, the Iroquois snuck away from his fellows, stole the bag containing the foot of his erstwhile companion, and threw it in the river.

When they reached the trading post, the voyageurs delivered the Iroquois up to the fort’s factor, Mr. McMullan, and told him that they suspected he had murdered and cannibalized his companions. Without sufficient evidence to convict him of murder, the factor sent the Indian to a distant post in New Caledonia, in what is now northern British Columbia.

“I had previously travelled several hundreds of miles with the son of this very man,” Kane wrote, “who always behaved well, although there certainly was something repulsive in his appearance, which would have made me dislike to have had him for a companion in a situation such as above described.”

Alexander Ross’s Version

North West Company employee Ross Cox described a slightly different version of the event in his 1832 memoir Adventures on the Columbia River. In Cox’s tale, the unfortunate party of 1817 was comprised of six French-Canadian voyageurs and an English tailor named Holmes. After losing their canoe in the rapids, the party was compelled to proceed downriver, through what Cox described as “an almost impervious forest, the ground of which was covered with a strong growth of prickly underwood.”

Three days after the disaster, a voyageur named Macon perished from privation. “His surviving comrades,” Cox wrote, “[were] determined to keep off the fatal moment as long as possible. They therefore divided his remains in equal parts between them, on which they subsisted for some days…

“Holmes, the tailor, shortly followed Macon, and they continued for some time longer to sustain life on his emaciated body. It would be a painful repetition to detail the individual death of each man. Suffice it to say that in a little time, of the seven men, two only, named La Pierre and Dubois, remained alive.”

Sometime later, two natives who were passing through the area in a canoe spotted La Pierre’s forlorn figure standing on the banks of the Columbia. They rescued the starving voyageur and brought him to Spokane House.

During his subsequent interrogation, La Pierre told the fort’s factor that when he and Dubois became the last remaining survivors of their party, the two of them began to wander about aimlessly in search of Indians. They made short work of their hideous provisions, and soon found themselves on the brink of starvation once again. At that point, La Pierre began to perceive an unnerving look that Dubois would flash him whenever he thought himself unobserved, and feared that his companion would attack him at the earliest opportunity. Sure enough, on the second night after their last meal, Dubois sprung at La Pierre and attempted to slash his throat with a knife. In the desperate struggle that ensued, Dubois gained control of the blade and opened the throat of his would-be murderer. A few days after the duel, he was discovered by the Indians and rescued.

“Thus far,” Cox wrote, “nothing at first appeared to impugn the veracity of his statement; but some other natives subsequently found the remains of two of the party near those of Dubois, mangled in such a manner as to induce them to think that they had been murdered; and as La Pierre’s story was by no means consistent in many of its details, the proprietors judged it advisable to transmit him to Canada for trial. Only one Indian attended; but as the testimony against him was merely circumstantial, and unsupported by corroborating evidence, he was acquitted.”

Today, the Rapids of the Dead lie below the Lake Revelstoke Reservoir, concealing their terrible secrets beneath a watery shroud. Although the banks of the Columbia bear no monument to the men, women, and children who lost their lives in its once-treacherous waters, the Workers’ Memorial Archway, which straddles a riverside path at the southern end of Revelstoke, rather fittingly commemorates all those who lost their lives in the line of duty.

Sources

- Narrative of the Sufferings of a Company of Emigrants in the Mountains of California, in the winter of ’46 and ‘7 by J.F. Reed, late of Sangamon County Illinois,” by J.H. Merryman, from the notes written by J.F. Reed, in the December 9th, 1847 issue of the Illinois Journal

- Travels and Adventures Among the Indians of North America from Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again (1858), by Paul Kane

- Adventures on the Columbia River: Including the Narrative of a Residence of Six Years on the Western Side of the Rocky Mountains, Among Various Tribes of Indians Hitherto Unknown: Together with a Journey Across the American Continent (1832), by Ross Cox

- This Blessed Wilderness: Archibald McDonald’s Letters from the Columbia, 1822-44 (2001), by Jean Murray Cole

Leave a Reply