How the Sasquatch Got Its Name

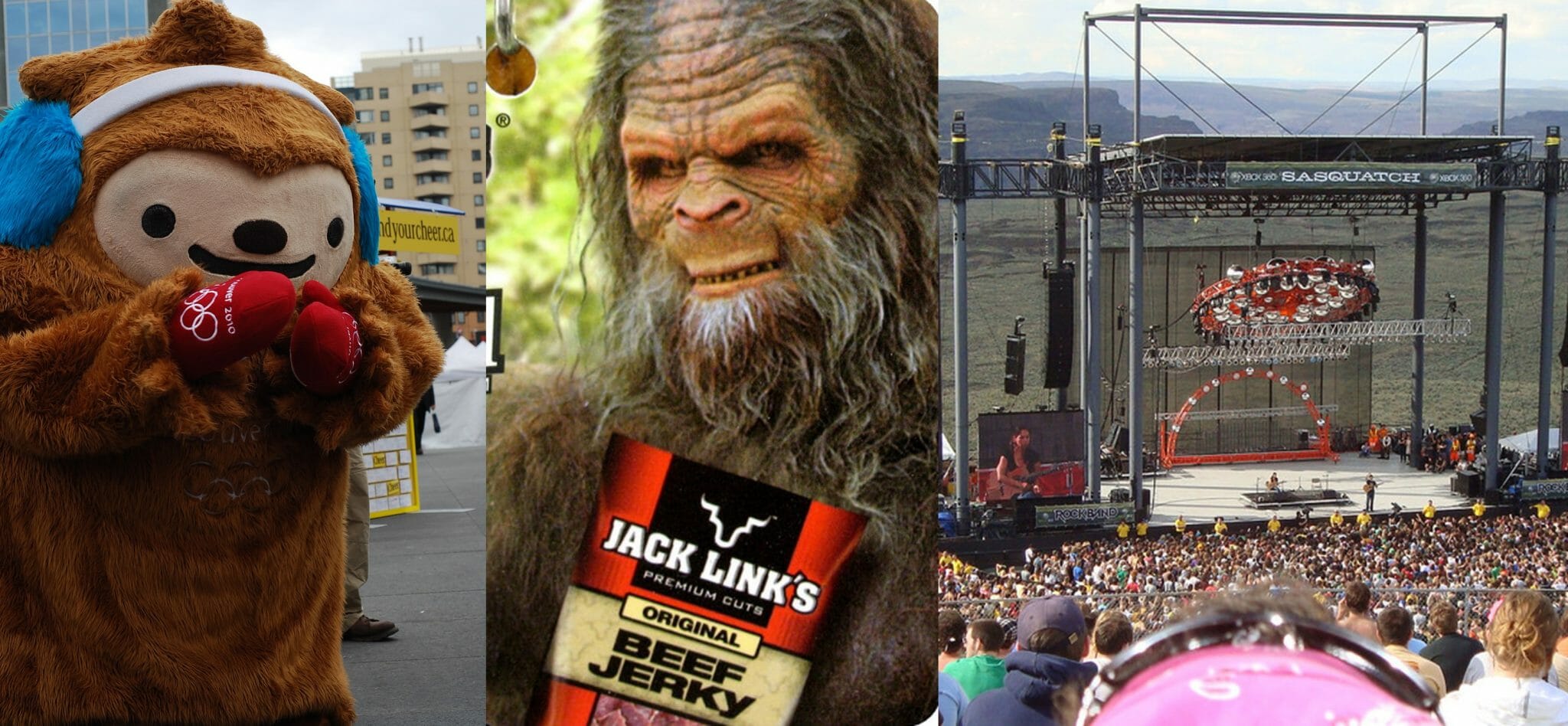

In British Columbia and the Northwestern United States, the Sasquatch hardly needs an introduction. This elusive, wild, hairy giant, once an obscure character of First Nations’ lore, now serves as an icon of the Pacific Northwest. Eight years ago, it inspired Quatchi, a monstrous mascot for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, BC. For twelve years, it has featured in Messin’ With Sasquatch– a series of hilarious Jack Link’s beef jerky commercials in which it is portrayed as the vengeful enemy of outdoorsy pranksters. And for sixteen years, it has shared its name with a famous Memorial Day music festival in George, Washington.

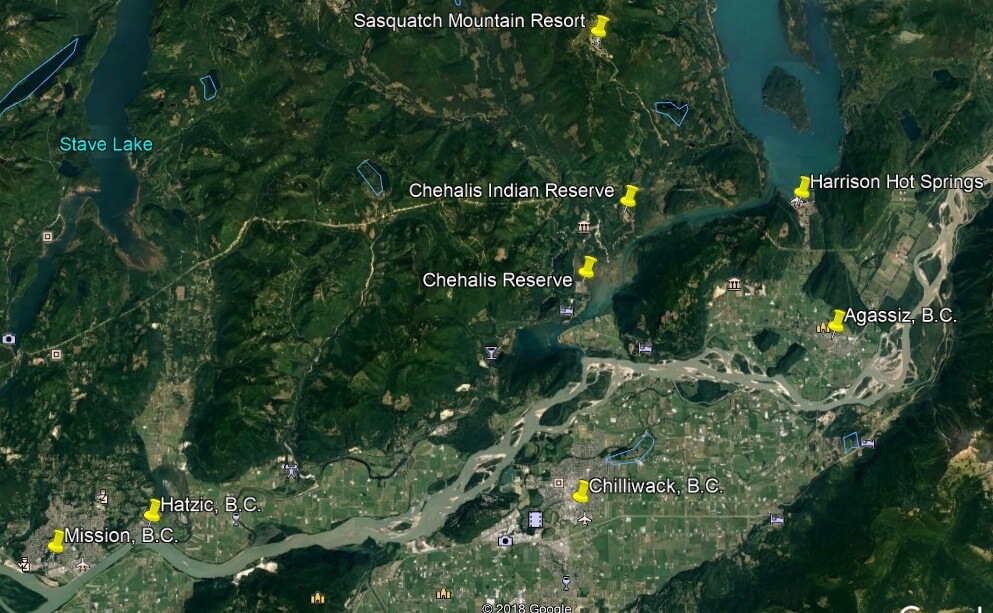

Another institution to which the Sasquatch lent its name is the Sasquatch Mountain Resort, a ski hill tucked away in the Douglas Mountains an hours’ drive north of Chilliwack, BC. The resort is aptly named, as most of its runs wind down the northeastern slope of Mount Keenan- a formation once known as Mount Morris, and the birthplace of the word “Sasquatch”.

The Origin of the Word “Sasquatch”

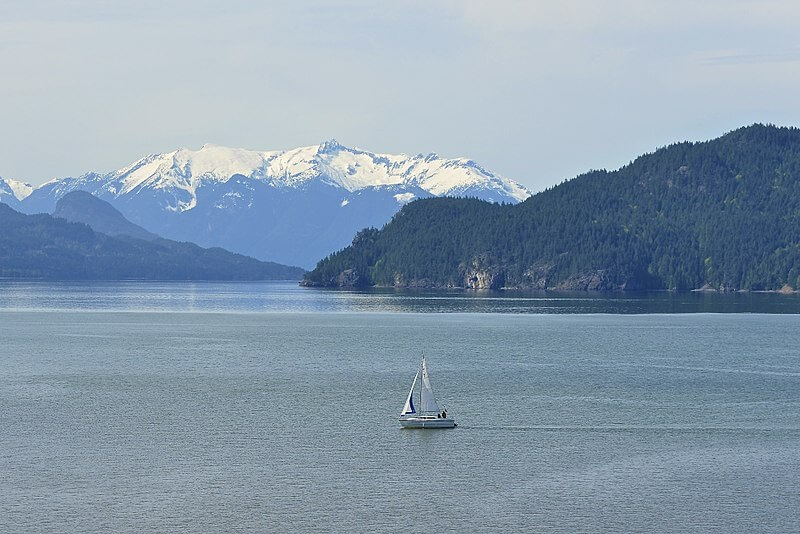

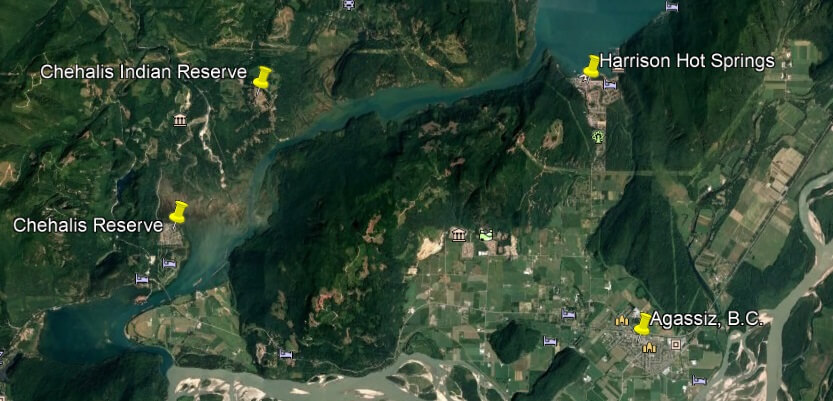

On the road from Chilliwack to the Sasquatch Mountain Resort, in the vicinity of the bridge over the Harrison River, lies the Chehalis Indian Reserve, home of the Chehalis First Nation.

The Chehalis people (not to be confused with their cousins from Puget Sound, with whom they share a name) are a Coast Salish people whose traditional territory revolves around the mouth of the Harrison River, a tributary of the Fraser.

Back in 1925, an Irish expat named John Walter Burns (born J.W. Bournes) became both the Indian agent and the schoolteacher at the Chehalis Reserve. Burns quickly earned the respect of the local natives and became fast friends with Frank Dan, a prominent Chehalis medicine man.

In those days, the Chehalis people were typically reluctant to share their stories with white men for fear of ridicule. Since J.W. Burns had demonstrated an open-mindedness towards their myths and legends, however, they eventually opened up to him and made him privy to some of their most carefully guarded secrets. Among the most intriguing of these were tales of wild hairy giants who, the Chehalis maintained, had inhabited the forests surrounding the Reserve since time immemorial. In 1929, Burns compiled some of these stories and published them in an article in the April 1, 1929 issue of the Canadian magazine Maclean’s, under the headline “Introducing B.C.’s Hairy Giants: A collection of strange tales about British Columbia’s wild men as told by those who say they have seen them.”

J.W. Burns’ Article

The tales of hairy wildmen recounted in J.W. Burns’ 1929 article in Maclean’s magazine are some of the most colourful of their kind to date.

The Wildman of Mount Morris

The first of these anecdotes details the experience of a Chehalis Indian man named Peter Williams in May 1909. While walking in the woods along the foot of Mount Morris about a mile from the Reserve, Williams heard a grunt in the bush. When he looked to see where the sound had come from, he found himself staring at what he first took to be a bear crouched atop a boulder about thirty feet away. As he raised his rifle to shoot the animal, it stood up and emitted a piercing scream. “It was a man,” said Williams. “A giant, no less than six and one-half feet in height, and covered in hair.” Enraged, the giant leapt from the boulder and tore after the Indian.

“I never ran so fast before or since,” said Williams, “through brush and undergrown toward the… Chehalis River [a tributary of the Harrison], where my dugout was moored.” Every so often, Williams glanced over his shoulder to check on his pursuer, who was quickly overtaking him. Williams narrowly escaped the monster by leaping into his boat and paddling downriver as fast as he could. “The swift river…” he said “did not in the least daunt the giant, for he began to wade it immediately.”

When he finally reached the safety of his cabin, Williams made sure that his wife and children were safe inside before bolting the door and barricading the entrance. “Then with my rifle ready,” Williams said, “I stood near the door and awaited his coming.”

After about twenty minutes, Williams heard a noise in the distance somewhat akin to the trampling of a horse. The noise became louder and louder. Williams eventually looked through a crack between the logs of the cabin wall and saw that the giant was approaching. “Darkness had not yet set in,” he said, “and I had a good look at him. Except that he was covered with hair and twice the bulk of the average man, there was nothing to distinguish him from the rest of us.”

When the monster reached the cabin, he began pushing the walls so that the structure rocked back and forth. The cabin creaked and groaned, yet by some miracle it managed to maintain its integrity. Clutching his rifle with trembling hands, Williams whispered for his wife to take the children and hide under the bed.

“After prowling and grunting like an animal around the house,” Williams continued, “he went away.” The family spent a restless night in the cabin, and in the morning Williams found the beast’s tracks in the mud outside, which were 22 inches long, “but narrow in proportion to their length.”

Peter Williams’ Second Encounter

The giant so damaged their cabin that the Williams’ family was forced to abandon it the following winter. Sometime later that season, Peter Williams went duck hunting on the north side of the Harrison River about two miles from the Reserve. Once again, he found himself face to face with the same hairy giant he had encountered the previous summer. As before, Williams ran for dear life, and the wildman chased after him. After about four hundred yards, however, the giant broke off and wandered back into the woods.

Interestingly, Peter’s brother, Paul, encountered the same creature later that afternoon. While he was fishing for salmon in a creek near the Reserve, the giant emerged from the forest and began to approach him. Terrified, Paul raced back towards his cabin with the monster hot on his heels. The giant gave up the chase shortly before Paul reached the cabin and walked back into the bush. Exhausted from fear and exertion, Paul collapsed in the snow and had to be carried inside by his mother and other relatives.

The Wild Couple of Harrison River

“The first and second time,” Williams told J.W. Burns, “I was all alone when I met this strange mountain creature. Then, early in the spring of the following year, another man and myself were bear hunting near the place where I found him. On this occasion, we ran into two of these giants.”

Initially, Williams and his companions thought the creatures were tree stumps. Suddenly, when they were about fifty feet away, the wildmen, who had been sitting on the ground, rose to their feet. Burns and his companion stopped dead in their tracks.

“We were close enough to know they were man and woman,” Williams said. “The woman was the smaller of the two, but neither of them as big or fierce-looking as the gent that chased me.” Williams and his friend ran home, and were not pursued.

Peter Williams’ Fourth and Final Sighting

One morning several weeks later, Williams and his wife were fishing in a canoe on the Harrison River not far from the Reserve. Upon paddling around a bend, they saw the same hairy giant that had destroyed their cabin the previous year. Fortunately, the monster took no notice of the Indians, and they made their escape without incident.

The Sasquatch Cave at Yale B.C.

Another wildman encounter Burns included in the article was the story of an elderly Indian named Charley Victor. Unlike Williams, Charley Victor was not a member of the Chehalis First Nation, but rather hailed from the Skwah Nation, a Coast Salish tribe from the Chilliwack area.

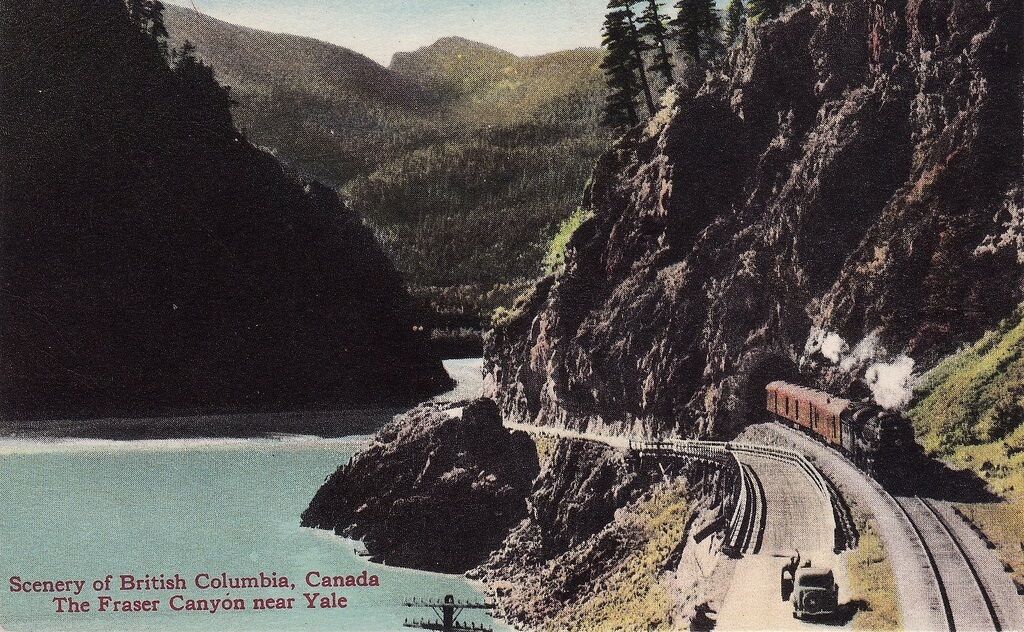

“The first time I came to know about these people,” Victor said, “I did not see anybody.” On this particular occasion, Victor was foraging with three other men on a rocky mountain slope about six miles from Yale- a town which lies on the CPR’s main line just north of Hope, BC. He and his companions were picking salmonberries- wild fruits similar to raspberries.

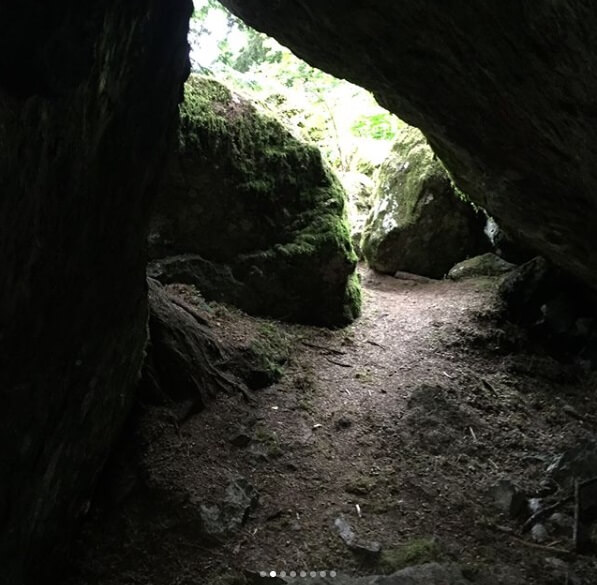

“In our search for berries,” Victor said, “we suddenly stumbled upon a large opening in the side of the mountain. This discovery greatly surprised all of us, for we knew every foot of the mountain, and we never knew nor heard there was a cave in the vicinity.”

Near the cave’s mouth was a massive boulder, which looked as though it once might have been employed as primitive door. The natives cautiously approached the cave and peered inside, but were unable to see anything on account of the darkness. In order to combat this, they gathered pitchwood (a type of pine heartwood naturally saturated with flammable resin), lit it on fire, and began to explore.

Not far from the mouth of the cave, the natives came upon a primitive stone house. “We couldn’t make a thorough examination,” Victor explained, “for our pitchwood kept going out. We left, intending to return in a couple of days and go on exploring.”

When Victor and his companions told the tale of their discovery to their fellow tribesmen back at the Reserve, the elders warned them not to venture near it again, as it was surely occupied by a wildman. “That was the first time I heard about the hairy men that inhabit the mountains,” Victor told Burns.

Disregarding the elders’ advice, Victor and his companions went back to explore the cave. When they reached it, they discovered, to their astonishment, that the massive boulder that stood near the entrance had been rolled back over the mouth, fitting so perfectly “that you might suppose it had been made for that purpose.”

Charley Victor’s First Encounter

About twenty years later, Charley Victor and a couple of his friends were bathing in a small lake near Yale, B.C. After he has finished bathing and had started to put on his clothes, a big hairy man stepped out from behind a rock only several feet away. “He looked at me for a moment,” Victor said. “His eyes were so kind-looking that I was about to speak with him, when he turned about and walked into the forest.”

The Wild Women of Hatzic, B.C.

In around 1914, Charley Victor had a second encounter with a hairy wild giant while hunting in the mountains near the village of Hatzic, just east of Mission, B.C.

On this excursion, Victor was accompanied by his dog. Upon hiking up to a plateau, his dog rushed over to a large cedar tree and began to growl and bark at it. Victor noticed that there was a large hole in the tree about seven feet from the ground, and that his dog apparently wanted to enter it. Victor lifted his dog up and watched it scurry into the hole.

Suddenly, a muffled cry issued from within the tree. Victor raised his rifle, thinking that his dog had encountered a bear. Sure enough, something large crawled out of the hole and fell to the ground. Instinctively, Victor took a shot at it- an action which he immediately regretted, for there at his feet sprawled a bleeding, naked, black-haired Caucasian boy of about twelve of fourteen years of age.

Horrified, Victor dropped his rifle and approached the boy to examine the extent of his injury. He saw that he had shot the boy in the leg, but before he had a chance to dress the wound, the boy cried out as if appealing for help from the forest.

“From across the mountain a long way off,” Victor said “rolled a booming voice.” Shortly thereafter, Victor heard the voice again, this time a little closer. The boy screamed again, as if in reply.

Although he was scared out of his wits, Victor’s conscience would not allow him to abandon the boy he had wounded. He waited on the plateau, his dog whimpering fearfully at his feet, while the boy guided his mysterious sylvan savoir to his location. “Less than a half-hour,” said Victor, “out of the depth of the forest came the strangest and wildest creature one could possibly see…”

“The hairy creature,” he continued, “for that was what it was, walked toward me without the slightest fear. The wild person was a woman. Her face was almost Negro black and her long straight hair fell to her waist. In height she would be about six feet, but her chest and shoulders were well above the average in breadth.”

Victor told Graves that, although he had already met several wildmen by this time, he had never seen anyone quite so savage in appearance as this woman. “I’m sure that if that wild woman laid hands on me,” Victor said, “she’d break every bone in my body.”

The creature glanced at the boy before rounding on Victor, her face contorted with rage. Then, something truly remarkable happened. Using St’at’imcets, the tongue of the Douglas First Nation (a branch of the Lillooet tribe whose members lived at the northern end of Harrison Lake), the wild woman snarled, “You have shot my friend!”

Victor, who knew the Douglas language, replied that he had mistaken the boy for a bear, and that he was sorry. Ignoring him, the wild woman proceeded to dance around the boy, chanting the word “yahoo” in a loud voice. Every time she vociferated, a similar reply came from the mountain.

Soon, the wild woman was joined by another creature like her, who carried a six-foot-long cord which Victor suspected was either a snake or the intestine of some animal. “But whatever it was,” he said, “she constantly struck the ground with it.”

At the end of this strange ceremony, the second wild woman effortlessly picked up the boy with one hairy hand. That accomplished, she turned towards Charley Victor, pointed the cord at him, and said, “Siwash, you’ll never kill another bear.” With that, the wild women and the boy disappeared into the woods.”

With tears in his eyes, Charley Victor admitted to J.W. Burns that, indeed, had had not shot a bear nor any other animal since that fateful day.

The Wild Man of Agassiz, B.C.

Another wildman story which J.W. Burns included in his article derives from a letter which Burns received from a young native man from Vancouver named William (or perhaps Herbert) Point.

According to the letter, Point and a native girl named Adaline August decided to pick wild hops one day in late September 1927, in the wilderness near Agassiz, B.C. When they were finished, they returned to August’s father’s orchard by way of the railroad track. Along the way, August noticed something walking along the tracks in their direction.

“I looked up,” wrote Point, “but paid no attention to it, as I thought it was some person on his way to Agassiz. But as he came closer we noticed that his appearance was very odd, and on coming still closer we stood still and were astonished, seeing that the creature was naked and covered with hair like an animal.” Nearly scared stiff, Point picked up two stones with which he intended to hit the creature if it decided to attack him or August.

“He was twice as big as the average man,” Point wrote of the creature, “with hands so long that they almost touched the ground. It seemed to me that his eyes were very large and the lower part of his nose was wide and spread over the greater part of his face…”

Terrified at the creature’s appearance, the teenagers ran all the way to Agassiz. There, they told the story of their encounter to a group of natives who were enjoying themselves after a day of berry-picking. The elders there informed them that the creature belonged to a race of hairy giants who had always lived in the mountains, making their homes in tunnels and caves.

Etymology of the Word “Sasquatch”

There are two factors which make J.W. Burns’ 1929 article in Maclean’s magazine especially remarkable. The first is that, in Charley Victor’s tale of the wild woman of Hatzic, the wild woman around whom the story revolves demonstrated the ability to speak, incidentally in the dialect of the Douglas First Nation. To the best of this author’s knowledge, this is the first of only two stories in which a North American wildman is purported to speak.

The second factor which makes Burns’ 1929 article truly remarkable is that is widely believed to be the first instance in which the word “Sasquatch” appears in print. Although there are older articles which reference the wildmen of the Pacific Northwest, Burns’ is the supposedly the first to actually refer to these creatures as “Sasquatch”- the name we know them by today.

The Accepted Explanation

Most sources which purport to explain the etymology of “Sasquatch” claim that the word is Burns’ Anglophonic perversion of the word “Sasq’ets”- a Halkomelem word meaning “hairy mountain man” (Halkomelem is a Coast Salish language spoken by the Chehalis, the Skwah, and other indigenous groups from the Fraser Delta).

Gian J. Quasar’s Theory

One researcher named Gian J. Quasar put forth an interesting alternative theory regarding the origin of the word “Sasquatch” in his book Recasting Bigfoot. Without citing any evidence to back his assertion, he claimed that the word “Sasquatch” was really a combination of two words: “Saskahaua”, and “Kinchotch”. “Saskahaua”, Quasar claimed, was the British Columbian district for which J.W. Burns became Indian agent. And “Kinchotch”, as Quasar correctly pointed out, is a Chinook Jargon term meaning “English”, which derived from the words “King George” (Chinook Jargon is an old pidgin trade language from the Pacific Northwest). According to Quasar, the Coast Salish Indians from the Fraser Delta area referred to hairy wildmen as “Saskahaua Kinchotch”- literally “Englishmen from Saskahaua”. J.W. Burns, Quasar claims, contracted this phrase into the simpler word “Sasquatch”.

There is one major problem with Quasar’s theory: to the best of this author’s knowledge, there was never a “Saskahaua” district in British Columbia.

A Closer Look at Burns’ Article

A closer look at J.W. Burns’ 1929 article reveals that the truth behind the origin of the word “Sasquatch” may have evaded both Gian Quasar and mainstream etymologists. In his article, Burns quotes Skwah Indian Charley Victor as saying of B.C.’s hairy giants:

“The strange people, of whom there are but few now- rarely seen and seldom met… are known by the name of Sasquatch, or, ‘the hairy mountain men’.”

Even more importantly, Burns later quotes directly from a letter written by William Point, the young native man from Vancouver who saw a wildman on the railroad tracks near Agassiz. An excerpt from this letter reads:

“Old Indians who were present said: the wild man was no doubt a ‘Sasquatch,’ a tribe of hairy people whom they claim have always lived in the mountains- in tunnels and caves.”

Assuming that Burns faithfully recorded these lines as they were said and written, it appears that the word “Sasquatch” may actually be an old Halkomelem word (or, at the very least, William Point’s interpretation of the Chehalis word for B.C.’s hairy wildmen) and not some invention of J.W. Burns’.

The Story Behind the Sasquatch Mountain Resort

At the beginning of this article, we mentioned that Mount Keenan (formerly Mount Morris), home of the Sasquatch Mountain Resort, is the birthplace of the word “Sasquatch”. Indeed, it is the setting of the first story of Burns’ article, in which Chehalis man Peter Williams had a brush with an angry Sasquatch at the mountain’s base.

In 1940, Burns wrote another even more dramatic story of a Sasquatch encounter on Mount Keenan which is perhaps the most extraordinary Sasquatch story ever written. This tale is so remarkable that it deserves an article all to itself. If this interests you, please check in with us next week to discover the incredible story behind the naming of the Sasquatch Mountain Resort.

Sources

- Further Delving Into the Fascinating Life of J W Burns, from the June 2017 issue of the BCSCC (British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club) Quarterly, courtesy of American Fortean researcher Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra.

- Introducing B.C.’s Hairy Giants: A collection of strange tales about British Columbia’s wild men as told by those who say they have seen them, by J.W. Burns in the April 1, 1929 issue of the magazine Maclean’s.

- Recasting Bigfoot (2010), by Gian J. Quasar

- Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life (1961), Ivan T. Sanderson

- Are They the Last Cavemen? British Columbia Startled by the Appearance of ‘Sasquatch’, a Strange Race of Hairy Giants, in the July 29, 1934 issue of the Sunday Journal and Star (Lincoln, Nebraska), by Francis Dickie

Want to Give Us a Hand?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

P

Interesting, although the story of Charlie Victor and his friends makes me wonder about these three boys old enough to go out exploring and find a cave, then return home and tell adults about it. Charlie reportedly says this to Burns:

“That was the first time I heard about the hairy men that inhabit the mountains”

Really? If meeting the Hairy Man was so important, as suggested in the other stories, these boys should have:

– already known of it’s existence

– had some idea how to deal with it

This doesn’t make sense and sounds as if it was merely added to the account afterwards. I suggest you edit it.

Hammerson Peters

Thanks for the comment. That’s a direct quote from Burns’ article, and I’m going to leave it in.