John Ware

In 1874, the North West Mounted Police marched from Manitoba to a lawless frontier- a land which would one day become Southern Alberta. With tact and diplomacy, they quickly brought law and order to Canada’s Wild West. By the late 1870’s, the buffalo which once dominated the Canadian prairies were reduced to a scattering of tiny herds, making way for another bovine breed which would come to serve as a symbol of the province: cattle. Similarly, by the 1880’s, the whisky traders, wolfers, and prospectors who once made made up the region’s non-aboriginal population were supplanted by another breed of frontiersman: the cowboy. Of all of Southern Alberta’s early cowpokes, perhaps the most beloved was a friendly black wrangler named John Ware.

Slavery

John Ware was born into a life of slavery on a South Carolinian plantation sometime in 1845. Little is known about his early life, although his lowly status, coupled with his actions as a freeman, suggest that it was anything but pleasant. In 1863, at the end of the American Civil War, US President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As a result, John Ware, along with 3 million fellow American slaves, went free.

Texas

As soon as he was able, the eighteen-year-old freeman left the Black Belt for the West, never to return. First, he traveled to Texas, where the ranching industry was in full bloom. There, the former slave decided to try his hand as a cowpoke.

Said historian Grant McEwan of Ware’s early career in the saddle: “John Ware was not a good cattleman. He’d never chased a steer in his life. But he had some ambition.” This ambition ultimately drove him to Fort Worth in Northeastern Texas. In that old frontier town, he secured a position as a steer herder.

Even at eighteen, John Ware was an enormous man. Tall, muscular, and strong as an ox, his physical ability, in the eyes of his employers, made up for his complete lack of experience. He was a fast learner and, once given the opportunity, quickly honed his skills as a horseman. Soon, he found himself driving cattle northwest across the Great Plains, bound for Montana.

Montana

By all accounts, John Ware was a kind, friendly, good-natured man who was always quick to lend a helping hand. His amiable demeanor endeared him to many of his fellow cowpokes on the journey to Montana. One of the men with whom he became fast friends was a cowboy named Bill Moodie.

After many days in the saddle, the company finally arrived in Montana. Shortly after delivering their long-horned cargo, they were approached by a seasoned cattle driver named Tom Lynch. Lynch had been hired by a Canadian rancher named Fred Stimson to drive a herd of 3,000 cattle north across the border. He needed extra cowhands to help him with the task, and invited Bill Moodie to join his team. Moodie agreed, on the condition that Lynch also hire John Ware. Tom Lynch accepted Moodie’s condition, and in no time, John Ware was riding for Canada.

The Journey North

Somewhere along the trail to the Great White North, John Ware asked Lynch for a more spirited horse. The veteran cowboy obliged, bringing the greenhorn a wild mustang which he was certain he would be unable to break. While his fellow cowhands stood by in anticipation, Ware vaulted up onto the animal’s back. Immediately, the bronco began to buck wildly, furiously struggling to rid itself of the unwanted rider. Ware held on for dear life, desperately gripping the horse’s ribs with his powerful legs. Due to either his incredible size or sheer nerve, or perhaps some combination thereof, Ware retained his mount. Eventually, he forced the bronco into submission. When his horse finally calmed down, his fellow cowboys told him that his performance was the best bronc riding they had ever seen.

On September 1882, John Ware rode into what would become Southern Alberta. It is said that when he got his first glimpse of the Albertan foothills and the Rocky Mountains beyond, he remarked, “If old Adam saw this, he’d want to sell the Garden of Eden.” Although he did not know it at the time, Ware was probably the third black person to set foot in the region. He was preceded by a whisky trader named William Bond, and by a household servant who had made the journey west with the family of former NWMP Commissioner James Macleod.

Eventually, John Ware and Lynch’s team arrived at their destination: Fred Stimson’s property on the Highwood River, the Bar U Ranch.

The Bar U Ranch

On Lynch’s recommendation, Fred Stimson hired John Ware to work at the Bar U Ranch. The South Carolinian greenhorn, he maintained, had proved himself to be an extremely competent cowhand and an enjoyable companion on the journey from Montana. Fred Stimson soon found that he was soon equally pleased with Ware’s abilities and pleasant nature.

John Ware’s first winter in Canada was a brutal shock. After the first snowfall of the year, Stimson sent him out to round up some scattered cattle. The big cowboy had spent all his life in the hot and humid climes of the Deep South. As such, he was ill prepared for the dry, bitter cold of an Albertan winter. Too cold to dismount, he spent four long days and three sleepless nights freezing in the saddle as he carried out his task. On the fourth day, he returned to the ranch house, chilled to the bone. Despite his condition, he remained, as Tom Lynch put it, as “cheerful as a woman with a new hat.”

Quorn Ranch

During his next few years working at the Bar U Ranch, John Ware acquired a reputation as a fine friend and an excellent cattleman. He earned the most respect, however, for his skills as a sportsman. On Sunday afternoons, he and his fellow ranchhands would get together and engage in calf roping, steer wrestling, bronc riding, and other rodeo sports. During these friendly competitions, John Ware proved himself to be one of the best rodeo cowboys on the Canadian plains.

Although he enjoyed his work at the Bar U immensely, John Ware eventually began to consider the notion of working for himself. In 1884, he decided to take the plunge. He bid farewell to his fellow cowboys and rode north to the town of Calgary, Alberta. There, he filed a homestead on Sheep Creek, a waterway situated about a third of the way from the Bar U to Calgary, near present-day Turner Valley.

After purchasing supplies, John Ware set to building a cabin on his new property. When he failed to complete the cabin before winter, he turned to ranch work once again. Instead of returning to the Bar U, he found employment at the nearby Quorn Ranch. This establishment sat on Sheep Creek not far from his homestead. The aristocratic Quorn Hunt Club of Leicestershire, England established it not long before to raise choice Irish horses for British gentry. John J. Barter, the ex-Hudson’s Bay Company man who managed the Quorn Ranch, tasked John Ware with managing the ranch’s horse herd.

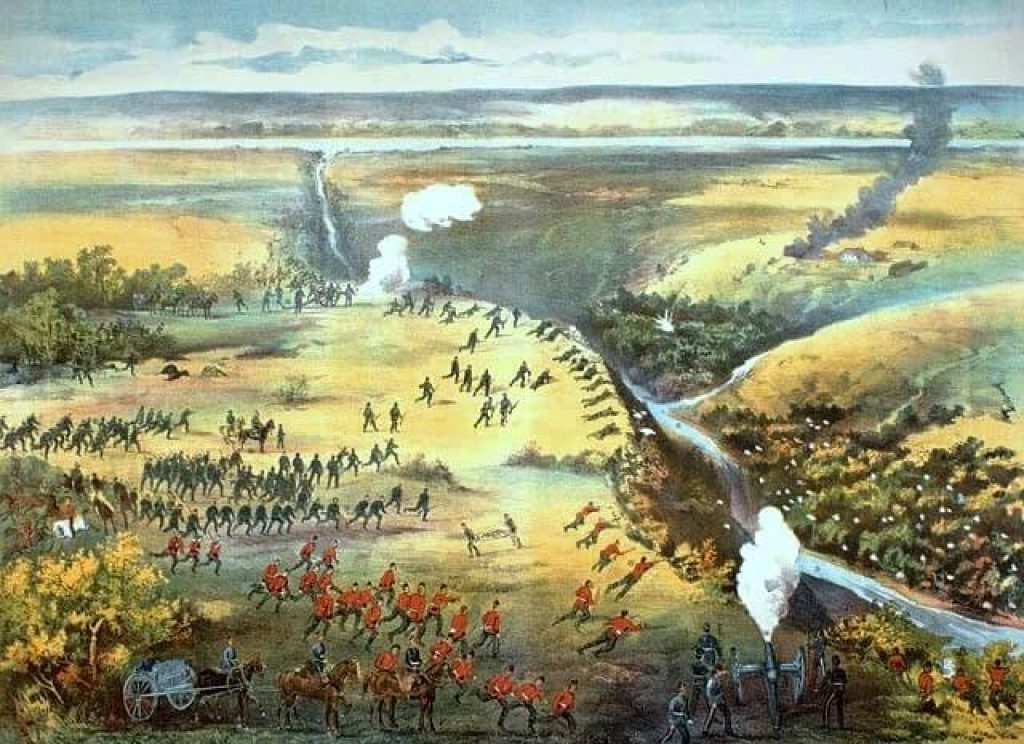

North-West Rebellion

That spring, John Ware signed on with a local militia which Fred Stimson established in order to defend the Calgary area from a potential military attack. At that time, the Canadian government was at war with Louis Riel’s Metis and Cree revolutionaries. Militiamen and Mounties alike fought to quell the North-West Rebellion in what would become Central Saskatchewan. Residents of the Rocky Mountain foothills feared that the local Blackfoot might join Riel’s cause and thought it best to prepare for potential hostilities. They need not have worried; the Blackfoot refused to take up arms against Canadian government forces, and the North-West Rebellion was quickly suppressed.

When life returned to normal, John Ware resumed his work at the Quorn Ranch. There, he ingratiated himself with both his fellow cowboys and his blue-blooded employers. According to an article in the June 23, 1885 issue of Fort Macleod‘s Macleod Gazette, “John is not only one of the best-natured and most obliging fellows in the country, but he is one of the shrewdest cow men, and the man is considered pretty lucky who has him to look after his interest. The horse is not running on the prairie which John cannot ride.”

Homestead

By the summer of 1885, John Ware divided much of his time between the Quorn Ranch and his own homestead on Sheep Creek. Earlier that spring, he registered a brand for his own cattle. The symbol he chose for his brand was ‘9999’, perhaps due to the fact that he could afford nine head of cattle at that time. Years later, Ware reduced his brand to ‘999’ out of concern that a four-digit brand was excessively painful for the cattle to which it was applied.

The winter of 1886 was disastrous for the ranchers of what would become Southern Alberta. Cattle starved to death on account of heavy snowfall which precluded access to their food. That winter, John Ware lost half his herd.

Marriage

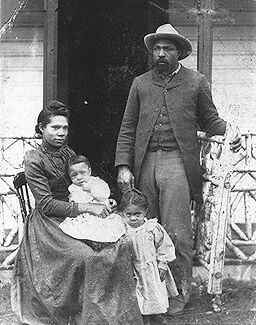

In 1891, John Barter introduced John Ware to the Lewis family, a black family recently arrived in Calgary from Ontario. Ware immediately took a fancy to the Lewis’ eldest daughter, Mildred. That Christmas, Ware asked Mildred to be his wife. The young lady accepted the proposal, and the two were married on February 29, 1892, in Calgary’s First Baptist Church. An article in the Calgary Tribune claimed that “probably no man in the district has a greater number of warm personal friends than the groom.”

The following year, on March 9, 1893, Mildred gave birth to their first child, Amanda “Nettie” Janet. She was the first of five children John and Mildred had together.

Red Deer River

For nine happy years, John and Mildred raised their family on their ranch on Sheep Creek. The Ware family was well-liked by local ranchers, Mildred being a gracious hostess and John always willing to lend a helping hand to a neighbour in need.

Ever since the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, settlers from Europe and Eastern Canada began streaming into the Canadian prairies, hoping to secure for themselves and their families a piece of the so-called “Last Best West.” These newcomers often found themselves competing for land with old-time ranchers. In order to avoid such competition, John Ware decided to rebuild his ranch on a more remote piece of real estate. In 1902, he relocated his family to a stretch of land along the Red Deer River near what is now Duchess, a village situated just north of Brooks, Alberta.

Tragedy

1902 was a year of tragedy for John Ware and his family. Not long after moving to their new home on the Red Deer River, Mildred gave birth to twin boys. Sadly, one of them passed away shortly thereafter. Mildred was severely weakened by the affair, and would never fully recover her health.

Shortly after the birth, the Red Deer River flooded and washed away the Ware’s home. John and his family packed their belongings and relocated alongside a tributary of the river which would come to be known as Ware Creek. That winter, Mildred came down with typhus and pneumonia. Although John rode for seven hours through a raging blizzard in order to get medicine for his sick wife, his efforts were in vain. Mildred passed away on March 30, 1905.

In the wake of his wife’s passing, a bereaved John Ware sent his youngest children to live with Mildred’s mother in the town of Blairmore in the Crowsnest Pass. Five months later, while out riding with his eldest son, his horse stepped in a badger hole and fell on top of him, killing him instantly. His subsequent funeral in Calgary was the largest the town had ever seen. The cowboy’s eulogy went thus:

“John Ware was a man with a beautiful skin. Every human’s skin is as beautiful as the character of the person who wears it. To know John Ware was to know a gentleman, one of God’s gentleman. Never again will a see a coloured skin as anything but lovely.”

Sources

Faces of History– John Ware: The Good Neighbour, Great North Productions Inc., 1995

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

Leave a Reply