The Texas of Canada?

Alberta has often been called ‘The Texas of Canada’, and with good reason; like its American counterpart, so-called ‘Wild Rose Country’ has traditionally been a bastion of cowboy culture, conservative values, and perhaps most importantly, the oil and gas industry.

For as long as it’s been a province, ‘The Texas of Canada’ has been a favorite place for ranchers to set up shop, and for as long as it’s had ranchers, Alberta has had a strong cowboy culture. The province boasts the Raymond and Medicine Hat Stampedes, two of the oldest rodeos in the world, as well as the world-famous Calgary Stampede. Calgary itself, with its sprawling herd of cow sculptures and popular country bars, bears the nickname ‘Cow Town’.

In fact, one of the most popular bars in Calgary is actually called Cowboys. Calgary boasts a professional hockey team, the Calgary Flames, which plays in a saddle-shaped arena called the ‘Saddledome’ (the Flame’s former barn is called the ‘Corral’). All throughout the province, you’ll find “I Love Alberta Beef” stickers pasted on truck bumpers, relics of the wave of province-wide solidarity which emerged in wake of the mad cow crisis of 2003. One need only drive a kilometre or two down any stretch of the Albertan Trans-Canada to see why cowboy culture is so locally prominent. No matter where you go on the Alberta #1, it seems, you’ll find huge herds of horses and cattle grazing behind barbed wire. Alberta is Canada’s largest beef producing province, and it contains about 41% of the nation’s cattle.

In addition to its cowboy culture, Alberta, like Texas, is famous for its social conservatism. Since the 1930’s , Alberta has repeatedly elected right-wing political parties to govern itself. The conservative Alberta Social Credit Party reigned in Alberta from 1935-1971, and the centre-right Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta governed the province from 1971-2015.

Last, but certainly not least, Alberta resembles Texas in that it is the undisputed centre of the Canadian oil and gas industry. ‘Wild Rose Country’ lies at the heart of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, a massive geological region which contains the world’s third largest reserves of oil and natural gas (eclipsed only by the oil sands of Saudi Arabia and Venezuela). As such, Alberta accounts for about 80% of Canada’s oil and gas production. Up until quite recently, you could find pump jacks all over the province working day and night, pumping oil from completed wells. Here and there, you’d come across massive derricks on which crews worked around the clock to drill new wells. Due to the incredible revenue generated by the oil and gas industry, Alberta has traditionally had the strongest provincial economy in the country.

Similar to the ranching industry, the oil and gas industry has made a profound mark upon Albertan culture. Edmonton, the capital of the province, is the home of the Edmonton Oilers, a professional ice hockey team with an impressive list of alumni, including Canadian hockey legend Wayne Gretzky. The Oilers got their name from the nickname of the local junior hockey team, the Edmonton Oil Kings, which’s similarly-named successor plays in the Western Hockey League today. Calgary, the epicenter of the Albertan petroleum industry, is the home of the Calgary Roughnecks, a professional lacrosse team. “Roughneck” is another word for the floorhand of either a drilling rig or a service rig.

Throughout the 20th century, Alberta has been shaped, more than almost anything else, by these three elements. However, events of the past two years have indicated that, although ranching remains as strong in the province as it’s ever been, Alberta’s staunch sense of social conservatism and internationally-prominent petroleum industry may be going the way of the Albertosaurus. On May 5, 2016, Alberta departed from its traditional right-wing path by electing the centre-left New Democratic Party (NDP) to form a majority government. This was the first time in eighty years that Albertans have elected a left-leaning political party to govern their province. And in June 2014, the price of crude oil plummeted, and along with it the oil and gas industry which has dominated Alberta for over a century. Companies in all areas of the oil and gas industry, from seismic exploration companies to those offering well fraccing services, have gone bankrupt. Others have hacked at their budgets to stay afloat, and as a result, thousands of Albertans have lost their jobs. Pump jacks all over the province have slowed to a halt. No longer are drilling derricks a common sight on the horizon.

Some alarmists, looking to the future, fear that the Albertan oil and gas industry might be history. Perhaps one of the ways to address this fear is to look to the past, and examine the history of Albertan oil and gas.

Early Canadian Petroleum Industry

In order to put the history of Alberta’s oil and gas industry into context, it helps to take a look at the early history of the Canadian petroleum industry.

The first Canadian oil company, the International Mining and Manufacturing Company, was founded by Charles Tripp in 1851 near present-day Sarnia, Ontario. Tripp’s company searched for surface crude in the oily swamps of what is now southwestern Ontario. Not only did Tripp’s company extract oil from asphalt beds; it also dug for salt springs -underground reservoirs of saltwater from which salt can be extracted- and manufactured its own fuels and oil-based paints. Because Tripp’s company did its own petroleum exploration, extraction, and refining, it is considered the world’s first integrated oil company.

In 1857, a carriage maker named James Miller Williams took over Tripp’s company and named it the J.M. Williams & Company. Under Williams’ direction, the company used the crude oil it extracted to produce asphalt along with a relatively new substance: petroleum-based kerosene.

Ever since the 1700’s, Europeans, Americans, and residents of European colonies around the world used whale oil (rendered whale blubber) and sperm oil (a liquid wax obtained from the heads of sperm whales) as indoor lamp oil. The whaling industry peaked in the mid 1800’s, and then began to decline rapidly as whales around the world were hunted to near-extinction. Fortunately for both whales and lamp-users, a Canadian geologist named Abraham Gesner invented a coal-based lamp oil in 1846. He called the substance “kerosene”. Several years later, in 1851, an American inventor named Samuel Kier developed a method of producing kerosene from crude oil. In no time, this petroleum-based kerosene eclipsed whale oil in popularity as a lamp oil. Demand for this product, more than anything else, was the catalyst that first set the North American oil and gas industry into motion.

Buoyed by the growing demand for crude oil, Williams & Company began to dig around the gum beds of what was once called Black Creek, on the western end of the piece of land which separates Lake Huron from Lake Eirie. In the summer of 1858, one of the company’s wells struck oil. It was to be one of North America’s first commercial oil wells (along with Pennsylvania’s 1859 Drake Well). Williams’ discovery triggered North America’s first oil rush, and in no time the area around Black Creek swelled to a town of 4,000. The town was named Oil Springs.

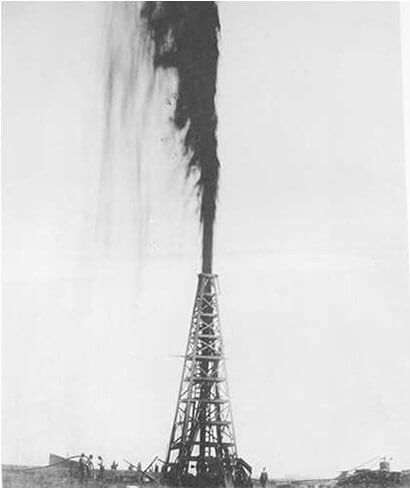

In 1860, Williams’ company, which was renamed the Canadian Oil Company that year, dug the world’s first “blowout”. A blowout, or gusher, is a geyser-like explosion of crude oil which occurs when an oil well penetrates a high-pressure underground reservoir. Dangerous, wasteful and destructive, blowouts would become a hallmark of the early oil and gas industry of the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Ever since that first gusher of 1860, blowouts would occur with some regularity until blowout preventers were developed in the 1920’s. Said the Hamilton Times of the 1860 incident:

“I have just time to mention that to-day at half past eleven o’clock, a.m., Mr. John Shaw, from Kingston, C. W., tapped a vein of oil in his well, at a depth of one hundred and fifty-eight feet in the rock, which filled the surface well, (forty-five feet to the rock) and the conductors [sic] in the course of fifteen minutes, and immediately commenced flowing. It will hardly be credited, but nevertheless such is the case, that the present enormous flow of oil cannot be estimated at less than two thousand barrels per day, (twenty-four hours), of pure oil, and the quantity increasing every hour. I saw three men in the course of one hour, fill fifty barrels from the flow of oil, which is running away in every direction; the flat presenting the appearance of a sea of oil. The excitement is intense, and hundreds are rushing from every quarter to see this extraordinary well.”

In 1866, oil was discovered at a location about 13 kilometres to the north, near Buttermilk Creek, ON. Almost overnight, many of those who worked at Oil Springs abandoned the place for the new diggings. A boomtown was established, which its inhabitants named Petrolia.

The oil men at Petrolia, instead of digging, developed a unique method of tapping into oil and gas reservoirs via drilling. This method was called the pole-tool method. Canadian oil men from the Petrolia oil fields became so adept at drilling that, once the oil and gas industry spread overseas, they became highly sought after for their expertise. Many Petrolia drillers, who became known as “hard oilers”, found themselves travelling to the far corners of the globe to teach their foreign counterparts how to locate and extract oil.

Southwestern Ontario’s short-lived oil boom quickly came to an end as the area’s underground reservoirs were gradually exhausted. In addition, Canadian oil companies struggled to compete with American oil magnate John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Although Canadian companies amalgamated in 1880 to form the Imperial Oil Company in an effort to contend with their American competitors, Canada slowly began to rely on imported American oil. And as quickly as it had began, Canada’s oil and gas industry appeared to be coming to an end.

Early Albertan Natural Gas

Although the Canadian petroleum industry certainly had its infancy in Ontario, it matured into a colossus in Western Canada, particularly in Alberta. The first hint of the massive Albertan oil and gas industry which would blossom in the mid-20th century occurred in 1883, when the Canadian Pacific Railway first came to Alberta from the east.

In 1883, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) built a bridge over the South Saskatchewan River at present-day Medicine Hat, in what is now southeast Alberta. Upon completion of the bridge, the CPR continued laying tracks westward. In December 1883, at a site approximately 35 west of the bridge, railway workers drilled for water. Instead of finding groundwater, however, the workers stumbled upon a rich reservoir of natural gas. The CPR used this gas for cooking and heating at the nearby railway section house which, similar to the old work site on the river (Medicine Hat), quickly grew into a rough community called Langevin Siding (today, Langevin Siding, which was renamed Carlstadt in 1910 by German immigrants, and re-renamed Alderson in 1915 in the midst of the anti-German sentiment of World War I, is a ghost town).

This discovery of natural gas encouraged further exploration. Locals quickly learned that the area was chock-full of the substance, and by the 1890’s, residents of nearby Medicine Hat were using the fuel for cooking and heating. At the turn of the century, Medicine Hat’s town council erected gas lamps all along what is now the historic downtown district and kept them fed with local natural gas. The council quickly discovered that it was cheaper to let the lamps burn perpetually than to hire someone to douse them each morning and relight them each evening, and so many of them have burned, day and night, for more than a century.

In June, 1904, a massive gas well was struck near Medicine Hat. The June 16 issue of the Medicine Hat News read, “Eureka We Have Found It! … There is no doubt now but that Medicine Hat will become the manufacturing centre of the west.” The discovery of industrial quantities of natural gas, along with quality clay found in the cutbanks along the river near Medicine Hat and the nearby town of Redcliff, resulted in a thriving brick and pottery industry which dominated the area in the early 20th century. In time, Medicine Hat earned the nickname “The Pittsburgh of the West” and “The Gas City” (the latter of which was the city’s official slogan until 2015). In 1907, English writer Rudyard Kipling visited the booming Medicine Hat and witnessed a flare from a freshly-drilled well. The writer famously remarked, “This part of the country seems to have all Hell for a basement and the only trapdoor appears to be in Medicine Hat.”

Early Albertan Oil

Arguably even more so than its natural gas, Alberta is known for its oil. Although present-day Alberta is famous- or perhaps infamous, depending on who you talk to- for the Athabascan bitumen pits in its north, Albertan oil was first discovered in the southwest corner of the province.

Perhaps the very first pioneer of the Albertan oil industry was a frontiersman known as Kootenay Brown. John George “Kootenay” Brown was one of the most interesting characters of the Canadian Wild West. Scots-English by ethnicity and Irish by birth, Brown secured a position as a junior officer of the British Army at the age of eighteen and served in India during the Sepoy Mutiny. His service in India left him with an appetite for adventure that would not be satiated by British military life. Upon returning to Ireland, Brown left the Old World for the New, never to return. His subsequent adventures on the Canadian and American frontier were many and varied. He toiled as a prospector in British Columbia during the Cariboo Gold Rush. He survived a Blackfoot ambush near present-day Medicine Hat, receiving an arrow in the back. He worked as a whisky trader in Manitoba, surviving a bloody shootout at Portage la Prairie. He rode in North Dakota for the Pony Express, narrowly escaping torture and death at the hands of chief Sitting Bull’s Sioux. He lived among the Metis of the Red River Valley. The list goes on and on.

Eventually, Brown settled in the Waterton (at that time known as Kootenay) Lakes region of southwestern Alberta. He knew from the local Kootenay and Stoney Indians that oil oozed along what is now Cameron Creek, Alberta. According to legend, the Indians informed him of the oil on Cameron Creek after he had given them a cocktail consisting of oil and molasses and asked them to inform him if they came across anything that tasted or smelled similar. Brown used the oil as lubricant for his wagons and as medicine for his horses.

Every once in a while, Brown would leave his home in the Waterton Lakes area and travel to the town of Fort Macleod, west of present-day Lethbridge, to sell fish and shoot the breeze with the locals. There, during the late 1880’s, he publicized the presence of oil in the Waterton Lakes region. Due in part to his yarns, a number of surveyors traveled to the area to investigate and returned with glowing reports. In no time, southwestern Alberta experienced its first oil boom. What is now Cameron Creek became known as Oil Creek, and Cameron Lake from which the creek flows became known as Oil Lake. Soon, wooden drilling derricks were being erected, and a small boom town came into being. The town was optimistically named Oil City.

However, the boom was short lived. According to the December 3, 1889 issue of the Fort Macleod Gazette, “Boring operations are at a standstill in the Kootenai oil regions. There seems to be great uncertainty as to when work will commence. Two holes have been sunk a short distance.” Apparently, the quality or quantity of oil in the Waterton Lakes area was not as great as the surveyors had anticipated. Before the year was out, Oil City was little more than a memory.

In 1902, John Lineham of the Rocky Mountain Development Company returned to the region south of Waterton Lakes and drilled the first successful oil well in Western Canada. Lineham’s well produced oil at 300 barrels a day. The well produced about 8,000 barrels of crude oil in its lifetime, and was abandoned in 1904. Today, a small monument depicting a drilling rig marks the site of Lineham’s well, the first of many productive Western Canadian oil wells.

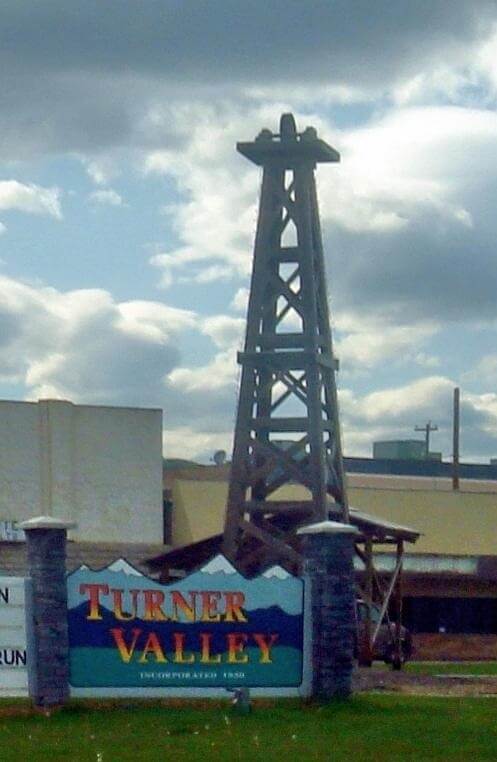

Turner Valley

The world changed forever in the late 19th century with the invention of the internal combustion engine. Henry Ford’s Model T, first produced in 1908, sounded the death knell of the steam locomotive and ushered in the era of the automobile. Along with the massive popularity of the world’s first affordable car came a huge demand for gasoline, and along with that came a huge demand for crude oil. By 1914, the world was as hungry for black gold as America was for the real stuff seventeen years prior, at the dawn of the Klondike Gold Rush. Enterprising Canadians were itching to stretch their entrepreneurial muscles, and would jump at the first hint of oil.

On May 14, 1914, a sort of oil was discovered in Turner Valley, located southwest of Calgary. Literally overnight, within a 24-hour period, 500 different oil companies were formed. Well drilling commenced immediately. The oil produced in Turner Valley was really wet natural gas. When stripped of the natural gas, the liquid that remained could be used as a gasoline substitute which earned the name “skunk gas” from its skunky smell. This process of stripping the liquid of its natural gas was first pioneered in Turner Valley. At that time, “skunk gasoline” was far more valuable than the natural gas which was separated from it. Many refineries in the Turner Valley area eliminated the unwanted natural gas by flaring it off. The flames from these flares could be seen from miles around. One coulee in which these flares were concentrated was referred to by locals as “Hell’s Half Acre.”

Several months after the discovery in Turner Valley, on August 4, 1914, Britain entered the First World War. As Canada was officially a British dominion at that time, it followed suit. The tanks, military vehicles and aircraft of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and the Allied Powers all relied on either gasoline or diesel, and so demand for crude oil skyrocketed. As a result, drilling at Turner Valley continued throughout the Great War.

In 1924, Turner Valley experienced one of the most massive blowouts in Albertan history. Eventually, the well caught fire and burned non-stop for 21 days. Wild well control experts finally managed to get the well under control using steam and dynamite.

In 1929, a new oil and gas exploration technology was first put to the test in Turner Valley. Before then, geologists and surveyors employed very crude methods of predicting where oil and gas reservoirs might be found. With the advent of this new technology, however, surveyors could predict whether or not subterranean deposits of significance were to be found with a great degree of accuracy. This technology, seismic reflection technology, was first developed during World War I in an effort to locate enemy heavy artillery and submarines, respectively. The process of collecting seismic data involved blowing up strategically-placed dynamite in order to send seismic waves into the earth. The waves would reflect off bedrock and travel up to the surface, where strategically-placed geophones would convert the ground movement into voltage. Engineers would analyze the geophone data to determine what lay underground. Canada’s first seismic survey was conducted in Turner Valley in 1929.

During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, the oil and gas industry of Turner Valley ground to a halt. Many oil and gas workers who had thrived during the so-called “Roaring Twenties” found themselves unemployed. The situation was grim.

World War II

The Depression that had gripped Canada throughout the Dirty Thirties came to abruptly to an end on September 10, 1939, when Canada entered World War II. As was the case during the First World War, crude oil was once again in high demand. Not only was crude oil necessary for the gasoline and diesel engines that powered the Allied war machine overseas; it was necessary for the production of popular, newly-invented petroleum-based materials like nylon and synthetic rubber. Unfortunately, supply was very low, and Canada still relied quite heavily on imported oil. Canadian oilfields already in existence, like the one at Turner Valley, reached peak production during the War.

The Leduc Discovery

The most decisive event in Canadian oil and gas history, which transformed Alberta into an oil and gas province, occurred on February 13, 1947. That day, Imperial Oil discovered light oil during an exploratory drilling operation near the town of Leduc, Alberta, just south of Edmonton. That first well drilled in the Leduc area, called the Leduc No. 1, would change Alberta forever.

Throughout the ’20’s, ’30’s, and ’40’s, Imperial Oil had searched for alternatives to the oilfields of Turner Valley. The company drilled 133 wells in Alberta and Saskatchewan, all of which failed to yield commercially significant quantities of oil. Before the Leduc find, Imperial Oil was seriously considering abandoning the pursuit of oil and focusing on manufacturing synthetic gasoline from natural gas. The discovery at Leduc was a pleasant shock to the company. It was a stunning find which led to many subsequent discoveries of huge importance across the prairies, including the discovery of the Pembina oil field, the largest of its kind in the province. As a result of these major discoveries, billions of investment dollars poured into Alberta. Immigrants flocked to the province, looking for work. Soon, Edmonton and Calgary grew into major cities. Edmonton became the centre of production for many oil and gas operations, while Calgary housed many of those companys’ head offices. In no time, Alberta made the shift from a modest agricultural region to the wealthiest province in Canada.

Early Pipelines

In 1949, a division of Imperial Oil called Interprovincial Pipeline Limited (IPL; now Enbridge) began to survey potential pipeline routes from Alberta to central Canada. The first IPL pipeline, constructed in 1950, connected Edmonton, Alberta, to Regina, Saskatchewan. The pipeline was extended the following year to Superior, Wisconson, in the United States. Throughout the mid-late 1950’s, the company extended the pipeline deeper into Ontario. At the time of its construction, the Interprovincial Pipeline was the longest pipeline in the world.

Also in the early 1950’s, during the Korean War, the Trans Mountain Oil Pipeline Company constructed a pipeline from Edmonton to Vancouver so that Canadian petroleum might be more effectively shipped to the frontlines overseas. Like the Canadian Pacific Railway of the 1880’s, the pipeline’s construction through the Rocky Mountains was an extraordinary feat of engineering.

The Athabasca Oil Sands

When it comes to oil and gas, Alberta is arguably most famous- or infamous, depending on who you talk to- for its sprawling northern oil sands. Sometimes referred to as the Athabasca tar sands, this deposit is the largest known bitumen deposit in the world.

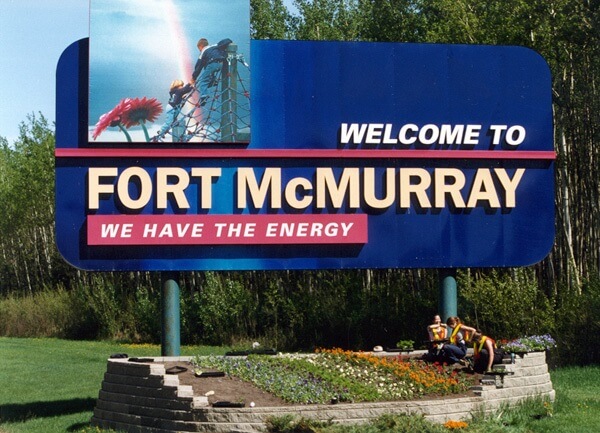

Canadians have known about the Athabascan bitumen deposit for centuries. Local Cree Indians used the tar-like substance to waterproof their canoes. Explorer Alexander Mackenzie wrote about the heavy oil that surfaced along the Athabasca River in the 1790’s. The Hudson’s Bay Company, which established the trading post Fort McMurray in the region in 1870, knew well that oil was to be found in the area. Despite the fact that the presence of oil in the area was common knowledge, the Athabasca oil sands were not exploited for their subterranean riches until the 1960’s.

For oil men of the mid-late 19th century, there were two problems with Athabascan oil. The first problem was that it could not be extracted through the conventional drilling methods of the time. Athabascan bitumen is a heavy, viscous mixture of clay, sand, and thick petroleum which cannot flow or be pumped in its raw form. The second problem with Athabascan bitumen is that it must be first separated into crude petroleum and sediment before it can be refined for use. During the early days of the Albertan oil and gas industry, the technology necessary to carry out this process had not yet been developed.

Although pioneering oil men dabbled in the Athabasca tar sands in the 1920’s and 1930’s, it was not until the 1960’s that the northern oil sands were seriously exploited. Instead of drilling wells in the area, oil companies extracted the bitumen by blasting and excavating huge open-pit surface mines. The heavy bitumen was chemically separated, or “cracked”, into sediment and less-viscous synthetic crude oil on site.

In 1967, Suncor’s antecessor, the Great Canadian Oil Sands, opened up a refining plant in the Athabasca region for this very purpose. Immediately, the area exploded in growth. The town of Fort McMurray, which revolved around the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post of the same name, quickly grew into a large boomtown.

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, an organization consisting of oil-rich Arabic OPEC nations, proclaimed an oil embargo. This was done in response to pro-Semitic American military involvement in the Yom Kippur War, which was being fought between Israel and a number of Arabic nations. Because of this embargo, oil prices around the world soared. This, in turn, sparked investor interest in the Athabasca oil sands, and the region continued to flourish.

The Recession of the 1980’s

Throughout the rest of 1970’s following this oil crisis of 1973, Alberta experienced an economic oil boom which some have likened to a modern-day gold rush. With oil prices sky high, entrepreneurs and adventurers flocked to Alberta to strike it rich. There were more jobs in Canada, particularly in Western Canada, than ever before. In the space of a few years, the province’s population increased by a third. Calgary and Edmonton grew rapidly, and as a result the housing market boomed. In 1978, in Fort McMurray, the Syncrude Mine opened. Today, the Syncrude bitumen mine is the largest mine by area in the world.

Suddenly, in the early 1980’s, the oil bubble burst. The Albertan oil and gas industry had overstretched itself, producing too much crude oil to quickly. Oil supply exceeded oil demand, and crude prices sunk to record lows. The Albertan petroleum industry was hit hard by the aftereffects of this oil glut which plunged the world into the biggest economic recession since the 1930’s. And as soon as it had begun, the Alberta oil boom was over.

Recovery

There was a light at the end of the tunnel. The Alberta oil and gas industry began to recover in the late 1980’s, and by the mid nineties, it had retained its former glory, thanks in part to the economically sound policies of Alberta premier Ralph Klein.

The Alberta petroleum industry continued to grow well into the 21st century. The growth was not only confined to Alberta, but also spread to southwest Saskatchewan and northeast British Columbia. By 2012, the Athabascan oil sands alone were producing an average of 1.8 million barrels of synthetic crude per day. In the early 2010’s, two massive pipeline projects were proposed. One, the international Keystone XL pipeline, was, after a long struggle, eventually given the green light. Construction commenced, and the Keystone XL pipeline now connects Hardisty, Alberta, with Houston, Texas. Another, the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline, was also proposed. This Enbridge pipeline would connect Brunderheim, Alberta, with Kitamat, BC. Due, in part, to strong resistance from BC First Nations communities and Canadian environmentalists like David Suzuki, however, the project has never come to fruition.

The Recession of 2014- …

In 2014, the price of crude oil began to drop, and has been steadily dropping ever since. As was the case in the 1980’s, this drop in oil prices was due to an overabundance of oil. Canadian and American oil companies had steadily been amping up production since the comeback of the ’90’s. Middle Eastern and African oil nations have worked furiously to supply the growing markets of China and India. Eventually, production outstripped demand, causing the oil prices to plummet, and with them the Alberta oil and gas industry.

All throughout 2014, 2015 and 2016, companies in the Albertan oil patch have cut their spending and laid off workers to stay afloat. Today, thousands of Albertans are unemployed. As was the case in the 1980’s, and in the 1930’s before that, the situation is grim.

Conclusion

According to popular belief, American writer Mark Twain once said, “History does’t repeat itself, but if often rhymes.” With this piece of wisdom in mind, it follows that Alberta, particularly its oil and gas industry, as it has in the past, will climb out of the economic slump it presently finds itself in sooner or later. Perhaps, as was the case following the recession of the ’80’s, Alberta’s newly-elected NDP government will adopt fiscally responsible policies which will assist in bringing Alberta’s dominant industry back to life. Let’s hope the comeback of the Alberta oil and gas industry, as was the case following the Great Depression, doesn’t take a World War III (knock on wood).

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online book store:

Leave a Reply