Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West(1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter VII: Lost on the Plains.

Chapter VIII

Among the Whisky Traders

WE REMAINED IN THIS camp until Sept. 29, when we received word from Ft. Benton, from Colonel Macleod, to the effect that we were only 60 miles from Ft. Whoopup, and that we were to move about 15 miles west, when we should strike a well beaten road leading to that place. This trail was the one used by traders coming up from Ft. Benton to trade with the Indians at the different forts and was much used. This was most welcome news, as the weather was growing cold and it was not a cheerful prospect to look forward to, spending the winter at the Sweet Grass hills. The messenger who brought the news gave us a good account of the country west. He said it was well wooded, with many rivers, and quantities of game. He also disabused our minds of the desperate character of the whisky traders and Indians. He told us the traders were few, most of them having returned to Benton for the winter with their summer loads of fur; that they had also had word of our advent, and we need not expect to catch many of them. The Indians were peaceable, he said, having an abundance of game, and were trading their wares amicably with the whites.

The horses being so few, and those left in such poor condition, we had to leave the guns and some wagons at the last camp, sending for them the following day. We rested in camp while they were being brought up. Our sugar and other necessaries had long since given out, but we had an abundance of antelope and buffalo meat.

While in camp Oct. 1 the first team of traders passed our camp going south with their summer pack of buffalo robes, which they had no

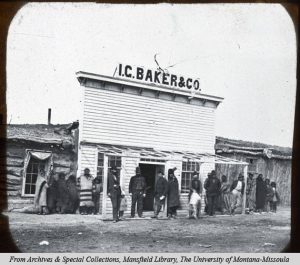

doubt traded for whisky. We searched this “outfit” as they called it in the west, but found no liquor. They were objects of great curiosity to us, and we plied them with questions. We camped on Milk river, Oct. 2, about 40 miles from Whoopup. At this point we waited until Colonel Macleod came up to us from the south, which he did Oct. 4. The weather had turned cold, and our fires were made with buffalo chips, as the dried dung is called. We hunted continuously, having no trouble in keeping a supply of meat on hand, only having to go just outside of the camp for game. The buffalo on one occasion came almost into camp, when one man killed six of them. Colonel Macleod was accompanied by Mr. Conrad and Jerry Potts, Blackfoot guide and interpreter, who was engaged at $90 per month, he knowing the country and Indians thoroughly. The halfbreed guides we brought with us had returned east with Colonel French. Mr. Conrad was one of the firm of I.G. Baker & Company, of Fort Benton, a firm doing a large general business in Montana. Mr. Conrad had been one of the first to build a trading post on Sheep creek, a point about 75 miles north of the present Fort Macleod. He had traded some time extensively in whisky, but had not done so for some years previous to our advent. Most of the traders in the North West purchased their goods from, and sold their furs to, this firm, who had the name of being responsible business men. It was composed of I.G. Baker, the head and originator of the firm in Benton many years before, when it was only a stockade trading post, and Charles and William Conrad, who carried on the firm. I.G. Baker resided in St. Louis. This firm did considerable contract work for the different military posts scattered through northern Montana, having their headquarters at Benton. At that time Benton was a very small place on the Missouri river, of only a few hundred inhabitants, and these altogether traders or stock men. This firm together with that of T.C. Powers & company, another equally wealthy firm, owned several steamboats that ran to that place from Bismark, several hundred miles down the river, every summer, bringing in large supplies of goods of all descriptions.

The commissioner while in Benton had contracted with the firm of I.G. Baker & company to furnish us with all supplies needed for a year, by the troops going west. A bull team was on the road loaded with forage and supplies of all kinds, but would not be up for a week or more. These trains were an institution peculiar to the prairies, there being three wagons covered with canvas, to each team, which consisted of 12 yoke of oxen. There were sometimes as many as eight teams of 24 wagons to a train. The wagons were often loaded with 7,000 pounds of freight each, or 21,000 pounds to a team, and their rate of travelling was slow, 10 or 15 miles per day, but sure, and they could haul through anything. There was one driver to each team. A night herder and cook completed the outfit, with generally two or three saddle horses along for herding the cattle at night. The men walked alongside their teams during the day, and their heavy bull whips, which they would crack with the noise of a pistol shot.

All the wagons except what were actually needed to take on the bedding and necessary forage and rations, together with the guns, and all the sick horses, were left in my charge with 20 men, at Milk river, to wait until the bull teams came up. They would haul the wagons on from that point until we joined the rest on Old Man’s river, at a point to which the guide, Jerry potts, was to take them. This was a suitable place to establish a permanent camp and build a fort. It is now known as Fort Macleod, the men giving it that name after we had built it, in honor of our commanding officer.

The guide, Potts, was a Piegan halfbreed and had made his home in the North West, being well acquainted with the country and all the Indians in it. We could not have gotten a better man, and as proof of his capability in that line, I may say that he was in the employ of the police until his death in 1899, at Fort Macleod, the point to which he first guided us, 30 years ago. The party I had with me numbered 20 men, some of whom were sick. Only one horse fit for service was left, being my trooper. The weather, while we remained there was cold, but fine, and we enjoyed the rest; our time was passed principally in shooting antelope or buffalo, which surrounded us in thousands. A few days after we camped here, John Glenn, a trader, passed from Benton, loaded with canned provisions, sugar, syrup, and a miscellaneous assortment. He made haste to reach the police when he heard we were in the country, expecting to make a good trade with us, knowing we had been on short allowance for a long time. His expectations were fully realized, as he on that trip laid the foundation of the tidy fortune he accumulated afterwards. He had been an old miner and trader and knew the country pretty thoroughly.

The men clubbed together and purchased a sack of flour, and a barrel of syrup, which they had to pay a pretty stiff price for. The flour cost $20 a sack, and the syrup $3 per gallon. It was a sight to see the way these unusual luxuries were disposed of. The cooking went on continually until they were all gone.

The bull train arrived in a little over a week later, and our wagons were strung on behind their teams. Some of the men were placed in the wagons, and some on foot, and we once more proceeded slowly on the journey.

We arrived in three days at the St. Mary’s river and camped not far from Fort Whoopup. It had already been searched by the troops ahead, but nothing had been discovered. On our way into the fort we passed a dead Indian, lying near the side of the road. He was an Assiniboine Indian, killed by the Blackfeet, their deadly enemies, and left lying where he fell. He had dried up like a mummy with the hot sun, and was minus the scamp, which the Blackfeet had taken as a trophy.

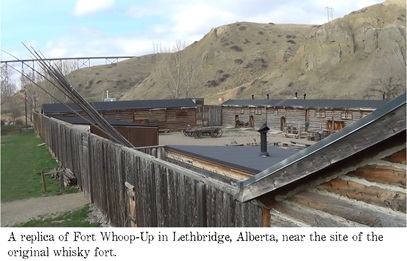

We found Whoopup to be a stockade fort, some hundred yards long and wide, being built in a square, out of solid cottonwood logs dovetailed together. The buildings on the four sides faced inward around the square. Loopholes had been cut in the bastions, and the fort was the proud possessor of two old fashioned brass field guns, which I doubt could have been used without bursting. Three or four men occupied the fort, being all traders, the owner of the post, D.W. Davis, doing the hospitalities. He took us over the fort and set before us a first-class dinner, with fresh vegetables of all sorts raised in his own garden. One of the rooms of the fort was used as a trading store, being full of Indian trading goods composed of blankets, cloth, brass and glass beads, and many other articles of Indian trade. They used coal in their stoves, there being a fine open seam not far from the fort. In fact all this river from that point down, abounds in coal. Where the Galt coal mine now is at Lethbridge, that point is only seven miles below Fort Whoopup.

We found Whoopup to be a stockade fort, some hundred yards long and wide, being built in a square, out of solid cottonwood logs dovetailed together. The buildings on the four sides faced inward around the square. Loopholes had been cut in the bastions, and the fort was the proud possessor of two old fashioned brass field guns, which I doubt could have been used without bursting. Three or four men occupied the fort, being all traders, the owner of the post, D.W. Davis, doing the hospitalities. He took us over the fort and set before us a first-class dinner, with fresh vegetables of all sorts raised in his own garden. One of the rooms of the fort was used as a trading store, being full of Indian trading goods composed of blankets, cloth, brass and glass beads, and many other articles of Indian trade. They used coal in their stoves, there being a fine open seam not far from the fort. In fact all this river from that point down, abounds in coal. Where the Galt coal mine now is at Lethbridge, that point is only seven miles below Fort Whoopup.

The men in this fort nearly all had Indian women, having married them according to the custom of the country by purchase, probably for whisky. The squaws were of good feature and physique, and dressed in calico were very well respectable in appearance. There were no Indians camped at this place. They had heard of our arrival and had gone out on the plains. The traders had also been notified of our approach, and no doubt had hidden what whisky they had, thus accounting for the non-success of the search made by the troops in passing. We crossed the St. Mary’s river a few miles above Whoopup, and started on the north side of that river for the main camp on Old Man’s river, some 20 miles way.

A rather ridiculous incident occurred while pulling up a steep hill on the opposite side. One of the wagons hitched behind one of the teams, was loaded with empty 9-pound shells for the guns. The wagon happened to upset, and the shells rolling out and down the hill, caused a general stampede among the bull whackers, who could not be induced to return for a considerable time. The team being left to its own sweet will, swerved off the road, upsetting one of the team wagons, in which the night herder was asleep. We expected to find the man dead, after taking bags of oats, flour, and several cook stoves from the top of him, but he was alive and none the worse for his shaking up. However it delayed us a considerable time and we only got as far as the top of the hill that night.

We crossed the Belly river again the next day, at a place named by the traders, Slide Out, which name it bears to this day. The Rocky mountains were seemingly quite close to us, looking grand with their white winter covering. They had been in sight ever since we left the Sweet Grass hills, and a grand view we had of them all along from that point. A high range of hills lying to the north, were also in sight for a long time. These are named the Porcupine hills, and lie on the north side of the Old Man’s river. We arrived at that river on the third day, and you may be sure we were greeted enthusiastically by call. They were camped on the river bottom, where there was cottonwood timber for miles on both sides of the river.

I was glad to be told that it was the intention to locate here permanently and build a log fort at once. No Indians had come in, but the time had not been wasted. There were two prisoners in camp, one a white man, Taylor by name, the other a Spanish negro, who had been captured the day before up the river, while endeavoring to go south, with several hundred buffalo robes, and a quantity of whisky. The whisky was spilled, and the robes and teams confiscated. The men were fined $250 each, and in default, imprisonment for six months. Taylor’s fine was paid, but the negro’s was not, and he was confined under guard in a tent, and on the fort being built, in the log guard house, from which during the winter he made a bold attempt to escape. He was fired at by the sentry but got away, though wounded. His body was found in the spring by Indians, about 40 miles south. Taylor became a respectable citizen, and after being in many different lines of business, settled down to hotel keeping, in which he still is. He faithfully adhered to his Indian wife, having a large family by her, all of whom he educated well.

It was a relief after all the hardships we had gone through to find that we were at last settled down permanently, with the new country before us to open up, and that the tedious march of 1874, that had taken us over four months to accomplish, was ended.

Continued in Chapter 9 – Building Fort Macleod.

Leave a Reply