The following article was originally published on my personal website in 2014.

The Tragedy of Tom Sukanen

If you drive about 10 kilometres south of Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, on the #2 Highway, you might notice a strip of antiquated buildings reminiscent of an early 1900’s Saskatchewan farming village located on a dirt to the right. This village, a collection of restored historical buildings hauled from the surrounding area, is the Sukanen Ship Pioneer Village and Museum. At the end of the village closest to the highway is a steamboat complete with a white cabin, red hull, and blue keel- a vessel christened the Sontiainen, more popularly known as the Sukanen Ship. This peculiar prairie ship- located more than a thousand kilometers from the nearest ocean- is the legacy of Tom Sukanen, an extraordinary Finnish-Canadian pioneer with an equally peculiar story.

The Land of Opportunity

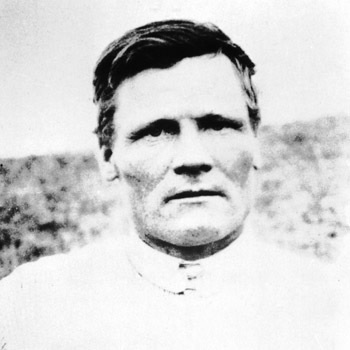

“Tom Sukanen” was born Tomi Jannus Alankola in the small village of Kurjenkyla, Finland, on September 23, 1878. Although little is known about his early life, amateur historians know from anecdotal evidence that Tomi, in his adolescence, apprenticed as a shipwright. In these early years, Tomi learned to build wooden ships, craft steel hulls, assemble steam engines, and combine the three components to create steamships. He also learned how to calculate latitude and longitude with a sextant, a skill that he purportedly honed on numerous nautical expeditions in the frigid Baltic, Barents and Norwegian Seas.

In 1898, 20-year-old Tomi, like thousands of young Scandinavians, boarded a steamship to America, the Land of Opportunity. He dreamed of a triumphant return to his homeland, with a large family and a small fortune. To help his prospects, he anglicized his name to Tom Sukanen.

In America, Sukanen- who was, by all accounts, a giant of a man in both size and ability- searched for a steel-working job, but met with little success. His quest took him to Minnesota, where he happened upon a young second-generation Finnish woman who was struggling to manage her late father’s farm. Sukanen married the girl and took up farming.

* According to another version of the tale, 28-year-old Sukanen married Sanna Liisa Rintala in Finland in 1906. Soon after, he sailed for America to avoid conscription in the Imperial Russian Army (at that time, Finland was a Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire), leaving his wife, pregnant with one of his daughters, at home in Finland.

The next year, Sukanen’s wife and baby daughter joined him in America. His wife, Sanna, had not responded well to his desertion, and had developed severe depression, and perhaps dementia, so debilitating that it prevented her from properly taking care of her infant daughter. To make matters worse, Sukanen refused to support his ailing wife and daughter, and accordingly spent three months in prison for his negligence. After serving his sentence, Sukanen immediately left Biwabik and embarked on his trek to Canada.*

By 1911, Sukanen and his wife, relatively destitute in spite of their efforts, had a son and three daughters. That year, Sukanen, on a whim, decided to travel north to Canada in search of his brother, Svant, who had a farm in the Macrorie-Birsay area about 90-110 kilometers south of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (roughly between Saskatoon and Swift Current), where the Canadian government was still offering free land in an effort to attract settlers. He hoped to take advantage of the opportunity, file a homestead, and immigrate to Canada with his family. With his effects on his back, he left Minnesota and, using the navigational skills he had acquired as an apprentice shipwright in Finland, made the 1000-kilometre journey across the prairie to south-central Saskatchewan on foot.

Upon arriving at the Macrorie-Birsay homestead and reuniting with his brother, Svante, Sukanen decided to start his own homestead about sixteen miles away. While waiting to receive clear title to his homestead, he ingratiated himself with his fellow homesteaders by helping them with their carpentry work, farm work, and machine repairs. A mechanical genius, Sukanen also built a number of home-made machines himself, including a small wooden steam-powered threshing machine, which he lent to his neighbours, and a sewing machine, which he lent to his neighbours’ wives. For himself, he constructed a tricycle, a wheat-puffing machine, and a handmade violin (Sukanen was reputed to be a proficient fiddler).

Soon, Sukanen received his homestead and began to work his own fields. His first few harvests were bountiful, and in time he acquired a respectable herd of livestock in addition to a minor fortune. During this time, the Finnish giant was sometimes seen manually hauling enormous loads of supplies from the store in Macrorie to his homestead, located ten kilometers away.

By 1918, Sukanen was making a comfortable living, and decided to return to Minnesota to collect his wife and children and bring them to Canada. Again, he made the journey on foot. Upon arriving in Minnesota, Sukanen discovered that his wife was dead. Years earlier, she had been committed to a psychiatric hospital in Fergus Falls, MN, where she expired after contracting the Spanish flu (according to another source, Sanna died in the asylum in 1914, four years before the 1918 international flu pandemic). Sukanen’s children, whose mother had been unable to care for them, had long since been put up for adoption. His two oldest daughters were adopted by one family, while his son and youngest daughter were both adopted by another.

Sukanen tracked down his son and convinced him to accompany him to Canada. The pair set on the long trek to Sukanen’s homestead, but were accosted at the Canadian-American border. The American authorities promptly returned the boy to his foster family (according to another source, the boy was put in a reform school) and threatened Sukanen with jail time if he ever attempted to smuggle his son out of the country again. Crestfallen, Sukanen returned to his homestead alone.

A New Ambition

Back in 1911, when Sukanen first set sail for the New World, he pictured himself returning to Finland one day with a wife and children. With his wife dead and children relocated, that dream was no longer a reality. Aimless and confused, Sukanen decided to distract himself by joining a rail gang. While labouring for the CPR, the big Finn amazed his foremen and fellow workers by singlehandedly unloading massive steel rails from the train cart- a job typically performed by at least three men.

As his body worked, his mind drifted, and over time Sukanen formulated his next big idea. Although he couldn’t return to Finland with a family anymore, he could still return in triumph. He envisioned himself a Captain, drifting into the Port of Helsinki at the wheel of a seaworthy steamship, every inch of which he, himself, had personally handcrafted.

Before Sukanen could wholeheartedly dedicate himself to the realization of his new dream, he had to determine whether or not it was feasible. In the summer of 1929, the 51-year-old appropriated a number of river maps from the Regina Department of Archives, built a sturdy rowboat and, without saying a word to his neighbours, set off down the South Saskatchewan River. He rode the current past Saskatoon and through Prince Albert, east of which the South Saskatchewan and North Saskatchewan merged to form the Saskatchewan River. He braved the white water near Grand Rapids, Manitoba, and followed the river into Cedar Lake and across the huge Lake Winnipeg beyond. After maneuvering his craft through a series of smaller Manitoban lakes, he entered the Nelson River and rowed his way northeast to Hudson’s Bay. There, the seaman secured a job on a freight steamer and worked his passage to Finland, where he spent some time with his family before returning to Saskatchewan.

Immediately upon returning to his homestead, the middle-aged Finn ordered huge shipments of raw materials, including massive steel sheets, thick steel rods, stout seasoned timbers, and thousands of nails and bolts. Satisfied that his venture was feasible, Sukanen began to build his ship.

The Great Depression

When his raw materials arrived at the Macrorie rail station, Sukanen, satisfied that he could sail a ship from Saskatchewan to Finland, got to work immediately. He planned to build the steamship’s deck cabins, hull, and keel separately, to float them downriver on a motorized raft, and to assemble them on the shores of Hudson’s Bay. First, Sukanen constructed the steam boiler. Equipped with little more than a hacksaw, a homemade forge, an anvil, and two stunted sledgehammers, the enormous Scandinavian cut half-inch-thick steel sheets to size and pounded them into cylindrical compliance. Next, he build the engine, forging all the individual components by hand. After completing the engine- a feat, according to a CPR engineer who beheld it years later, that would normally be accomplished with the use of a huge press- he set to work constructing the hull, and later the keel. Seemingly indefatigable, he laboured on his ship all day and well into the evening whenever his farming duties and Christian obligation permitted. Eventually, he neglected the farm work entirely and worked on his steamboat fulltime.

The incessant ringing of Sukanen’s hammer, coupled with the surfeit of supplies that constantly appeared at the rail station, piqued the curiosity of Sukanen’s neighbours. Throughout the early-mid 1930’s, curious farmers flocked from the surrounding countryside to marvel at the eccentric Finn and his crazy project. Eventually, their initial good-natured bewilderment gave way to bitter resentment, blowing away with the topsoil of their fields in the devastating dust storms that would characterize the “Dirty Thirties”. They wondered how this brilliant man, in good conscience, could expend his considerable savings on such a ridiculous project in the midst of such widespread poverty. Whenever confronted with his apparent selfishness and the frivolousness of his enterprise, Sukanen, deadpan, would wave his hand at the dusty, arid prairie and declare, with droll gravity, that a great flood was coming, and that he would sail away to Finland when it came. In time, Sukanen, once a respected homesteader admired for his ingenuity and resourcefulness, transformed into a despised recluse; the “Crazy Finn”; the Noah of the Plains.

Sukanen’s health deteriorated with his reputation. Completely absorbed with his work, the Scandinavian neglected his physical appearance; his face and clothing were perpetually black from the soot of his forge. Having exhausted all of his savings on supplies, Sukanen tore apart his barn, granaries and house for lumber, and started living in the cabins (in another version, under the hull) of his ship. Impoverished and purportedly too proud to accept charity, he subsisted on a meager diet of wheat kernels and rotten horseflesh. Malnutrition took its toll, and Sukanen lost a huge amount of weight, and much of his legendary strength along with it.

After seven years of hard labour, Sukanen had nearly completed his ship. He nailed thick tin plates (in another version, sheets of galvanized iron) to the keel to fortify it against arctic ice, and coated them in horse blood, an anticorrosion agent used by Finlanders for centuries. In a display of wry, self-deprecating wit, a characteristic for which Finns are famous, Sukanen christened his steamboat the “Sontiainen”- Finnish for “Little Dung Beetle.”

In 1938, Sukanen asked a neighbour, who owned a tractor, to help him move the keel and hull twenty seven miles to the river, where he had already moved the deck cabins in which he was living. To spite the pariah, and perhaps to save himself social condemnation, the farmer refused. Disheartened, Sukanen attempted to move the parts himself. First, he harnessed his few starving horses to the structures. When that failed, he resorted to dragging the hull and keel himself, using a makeshift winch and a set of iron wheels.

Although Sukanen made a little progress each day, he was a mere husk of his former self, and his famous strength was quickly waning. He became increasingly depressed. Eventually, Svant, concerned for his brother’s health, entreated the RCMP to bring Sukanen to an institution where he could recover his mental and physical strength and so, in 1930, RCMP Constable Bert Fisk accompanied Svante and his son Elmer to Sukanen’s homestead. There, they collected Sukanen, now too weak to stand on his own, and drove him to a mental hospital in North Battleford, Saskatchewan (about 130 km northwest of Saskatoon). In the end, he had moved the hull and keel less than five kilometres.

At the mental hospital, Sukanen slowly began to recover while being fed a steady diet consisting predominantly of raw fish, a Finnish staple. During this time, he wrote a strange, prophetic letter to his sister, who was living at that time in Spencer, Massachusetts. An excerpt from this letter reads:

“Four times there will be men who will try to raise and assemble this ship. Three times they will fail, but a fourth man will succeed. He will start the raising of my ship and it will sail across the prairies at speeds unheard of in this day and age, and will disappear in a mighty roar. My ship will go up and I shall rest in peace.”

One day, in the spring of 1943, Sukanen learned that his ship had been disassembled and looted by vandals, and that his tools and gear had been stolen. Heartbroken and purposeless, the Finnish giant died in the asylum shortly thereafter, on April 23, 1943. His body was interred in the North Battleford cemetery.

The Prophecies

“Four times there will be men who will try to raise and assemble this ship. Three times they will fail, but a fourth man will succeed. He will start the raising of my ship and it will sail across the prairies at speeds unheard of in this day and age, and will disappear in a mighty roar. My ship will go up and I shall rest in peace.”

In the four decades following Sukanen’s death, two of two of his prophecies would be realized.

The first, in a grotesque twist of fate, came true mere months after his death. The “great flood” that Sukanen had foretold, albeit facetiously, in the height of the Great Depression came to Saskatchewan in the summer of 1943.

The second, manifest in Sukanen’s cryptic letter to his sister, came true much later. In his letter, the Finn predicted that three men would attempt to raise his ship and fail. Upon his death, one of Sukanen’s few friends, a farmer named Victor Markkula, purchased what remained of the Sontiainen from the Macrorie municipality and stored it on his property. Victor’s son, Wilf, inherited the ship sections along with the farm after promising his father to keep them safe until the right man came along to put them back together. Wilf, who went on to own a hotel in White Bear, Saskatchewan (a hamlet located about 73 kilometers northwest of Swift Current, near the Great Sand Hills), dutifully kept his father’s farm and the remains of Sukanen’s steamboat, which he used to house chickens and store wheat. Over the years, three different men approached him with a desire to purchase and remove the Sontiainen. These three, as the prophecy foretold, failed in their endeavors; two ran out of money, and the third abandoned his undertaking after the South Saskatchewan River Valley flooded.

The fourth man, Laurence T. “Moon” Mullin- an antique collector who purportedly worked as a messenger for Al Capone’s henchmen in the tunnels of Moose Jaw in the 1920’s- came on the scene sometime later. He had heard rumors about the fabled “Sukanen Ship” and, as an antique collector, was naturally curious as to its whereabouts. As it turned out, his son, on a hunting trip, ran into Wilf Markkula in White Bear and learned the location of the ship’s resting place. Subsequently, Mullin met with Markkula, discovered the true tale of the Sukanen Ship, and became imbued with the same obsession that had consumed Sukanen in the 1930’s. He told Markkula that he resolved to retire and spend the remainder of his life working to restore the ship and erect it as a monument dedicated to the memory of the extraordinary man who built it. Impressed by the antique collector’s passion and sincerity, Markkula knew that he right man had come along, and decided to donate the ship to Mullin. True to his word, Mullin restored the Sontiainen and had it erected in the Pioneer Village and Museum south of Moose Jaw on the Saskatchewan Highway 2 north of Old Wives Lake, which became known thereafter as the Sukanen Ship Pioneer Village and Museum. True to Sukanen’s prophecy, on the day the restored Sontiainen was loaded onto a flatbed truck and transported to its new home, the steamboat ripped down the highway at speeds largely “unheard of” in the 1930’s, and disappeared in the “mighty roar” of the truck’s diesel engine.

The final part of Sukanen’s prophesy was realized when Mullins had Sukanen’s body exhumed in the North Battleford cemetery and interred in a small chapel in the Pioneer Village next to his ship. Finally, Tomi could rest in peace.

Sources

- http://www.sukanenmuseum.ca/tomi/tomi2.html; Laurence “Moon” Mullin, Eldon Owens, Dick Meacher; Edited by Erin Lough and Paul Johnson

- http://www.sukanenmuseum.ca/tomi/tomi3.html; Laurence “Moon” Mullin, Eldon Owens, Dick Meacher; Edited by Erin Lough and Paul Johnson

- http://www.sukanenmuseum.ca/tomi/tomi4.html; Laurence “Moon” Mullin, Eldon Owens, Dick Meacher; Edited by Erin Lough and Paul Johnson

- http://www.canadashistory.ca/Magazine/Online-Exclusive/Articles/Dreams-in-the-Dust-The-Story-of-Tom-Sukanen, Rick Book

Comments on the Original Article

Paul Friesen

Ray Pulkinen

I remember as a young lad, my Dad and I went to visit Tom, driving there with a team of horses and a buggy, as my Dad farmed land just west of Tom’s homestead. Tom was living beside the hull and keel which he had managed to winch a short distance from where he had constructed them. He was not a Crasy Finn as a lot depicted him. He was just obsessed by an overwhleming dream to sail back to his native Finland. His dream was so powerful that he did not realize that he would someday run out of money and eventually he would become old and weak. There just was not the equipment to be able to move this large and heavy sailboat to the river at that time. I have hunted for many years in the valley where he lived and have felt his spirit touch me powerfully, as so many others have also felt it. He had that Finnish “Sisu” which is unstoppable determination. I really do admire the courage and fortitude that our pioneers and ancestor’s had when they forged to open up this untamed country we now call Canada. I am so proud and blessed to have had the opportunity to understand what kind of unsurmountale obstacles and sufferings they endured to create the foundations of this great country! Let us keep our country strong and free!

Elaine Gill

I am so proud of all of the volunteers of this museum because I think it is so important to keep the memories of the past alive to see how far we have come! I am also thrilled that the Sukanen ship is there and that Tom is laid to rest beside his ship where he belongs. I have been reading everything I can get my hands on about this man and think he was a genius. When I read about his prophecy, it gives me chills! “Four times there will be men who will try to raise and assemble this ship. Three times they will fail, but a fourth man will succeed. He will start the raising of my ship and it will sail across the prairies at speeds unheard of in this day and age, and will disappear in a mighty roar. My ship will go up and I shall rest in peace.”

Carlene Graham

I know this story well. My father was the fourth man Moon Mullin. I remember standing in the school ground at Brownlee SK watching the ship go by on the highway. At the time I didn’t realize that day was the beginning of the next chapter in Tom Sukanen’s story. My farther became obsessed with the restoration. The entire family worked along side my father to bring life back to the ship. It was a difficult time for us. People began to think my father was “as crazy as old Tom”. But he too had a dream. We watched that dream come true as they raised the ship and flew the Finnish Flag from her bow. My dad saw to it that Tom’s story made it home to Finland. It is my understanding there is a statue of Tom in the town he came from. My daughters’s ashes rest with Tom at the museum linking our families together in eternity.

I remember driving past this ship years ago, but I remember it as the “Dontiainen”. Is my memory playing tricks on me?

My response to Mr. Friesen

Hi Paul, thanks for the comment! No, your memory isn’t playing tricks on you. From what I’ve gathered online, when the ship was salvaged by Laurence Mullin, the words painted on the hull were barely legible. The men who restored the ship misread the “S” as a “D” and called it the “Dontianen” accordingly. Sometime in the last 5 years, museum staff fixed the mistake.