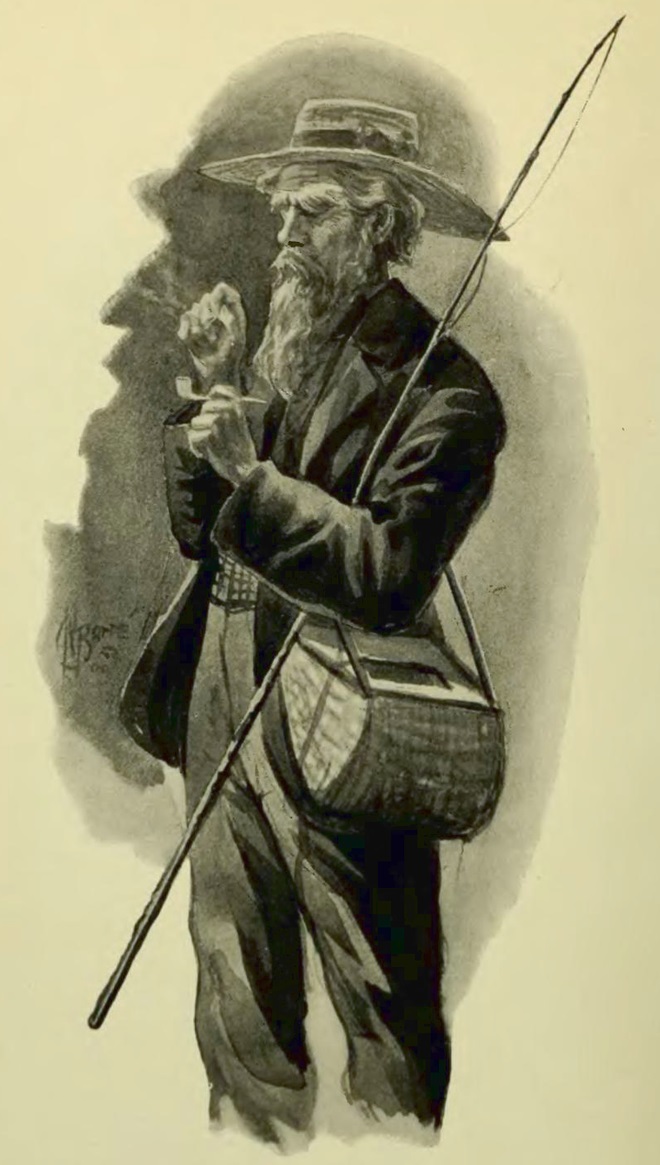

Le Pere Louison

La Chasse Galerie: Legendes Canadiennes (1900; English Translation); With Annotations by Hammerson Peters

Back to Honore Beaugrand’s Classic French-Canadian Folktales.

I

THERE ONCE WAS a tall old man, lean, straight as an arrow, as they say in the country, with a swarthy complexion, and his head and face covered with thick hair and a long salt-and-pepper beard.

All the villagers knew Father Louison, and his reputation even extended to neighboring parishes; his job as a ferryman put him in touch with all the foreigners who wanted to cross the St. Lawrence, a league in width in this place.

This section of the river had been nicknamed the Grand Trunk, a funny nickname by which it was generally known. The origin of its name is something of a mystery, as is that of its namesake, the railway [1] which provoked such acrimonious discussions in the political meetings of the time. Some said that the name came from Father Louison’s ferry, which comprised a canoe hollowed out in one piece from a gigantic tree trunk.

Although everyone in the village knew the Grand Trunk, no one could say the same about its history.

Father Louison had arrived at ‘L’ a long time ago – the old folks said that it was at least twenty-five years ago – without drum or trumpet. He had bought a small patch of land as big as his hand on the banks of the St. Lawrence, very close to the shore and a few acres from the church, where he had built a miserable hut with the remains of a boat cabin he had found one fine morning washed up on a nearby shore.

He earned his living with difficulty, ferrying travelers from one shore of the St. Lawrence to the other and fishing from the ice breakup until the last days of autumn. He was sure to take the first eel, the first walleye, the first bass and the first shad of the season. He also hunted bustards, ducks, plovers, larks and woodcocks with a long flintlock rifle that appeared to date from the French regime.

You never met him without his paddle, his rifle, or his fishing rod on his shoulder. He went quietly on his way, nodding pleasantly to the friendly greetings that most afforded him, and to the shy tips of the hat that he received from the children, who all considered him a bogeyman who was to be feared and avoided.

Despite being ignorant of his true history, most made it their mission to fabricate one, making it bad rather than good, because Father Louison loved and practiced solitude too much to have become popular among the villagers. He was generally satisfied with offering the products of his fishing or hunting to his usual customers: the parish priest, the doctor, the notary and the village merchant, and if the fish or game was exceptionally abundant, he would sell the surplus on the Joliette, Sorel, and Berthier markets.

If we allowed ourselves to take an honest look at his character, however, he could not be accused of any wrongdoing, because his reputation for integrity was known ten leagues around. He had even risked his life several times to save the reckless or the unfortunate who had almost perished on the waters of the St. Lawrence, and he had behaved in particular with the greatest bravery during a storm which had thrown large numbers of boats at the coast, flying to the rescue of the shipwrecked with his big canoe.

The priest further affirmed that Father Louison was a good man who fulfilled his religious duties with the utmost punctuality. Always ready to render a service when asked to, he made it a point to never ask for anything himself, and that was probably what he was not forgiven for.

The world is so funny and so capriciously selfish.

Every evening, at dusk on long summer days, the old man went to anchor his canoe with two or three ropes to the shore, in a place where he cast out his varveaux [2]. Sitting in the middle of his boat, he remained there in the most perfect stillness until late at night. Its silhouette was first cut out sharply and precisely on the mirror of the sleeping river, but soon took on indecisive lines like those from a painting by Millet, in the dark, when one only hears the murmur of small waves lazily caressing the silver sand of the shore.

The involuntary fear of Father Louison did not exist only in children; many a superstitious young woman, chatting with her lover under the large poplars lining the coast, had convulsively clutched the arm of her companion in seeing the old fisherman’s canoe in the last gleams of twilight.

In short, the poor old man was more feared than loved in the village, and the children involuntarily quickened their pace to a trot when they saw his taciturn figure in the distance.

II

There was at ‘L’ … a bad boy, as is found in all the villages of the world, and this kid hated Father Louison, of whom he was, however, terribly afraid. The old fisherman had caught this prankster one day when he was cruelly beating an old Barbet [3] dog which he had uselessly tried to drown. The old man had simply pulled the boy’s ear and threatened to tell his parents about his behavior.

Now, the father of the boy in question was a rough customer named Rivet, who sought rather than avoided a quarrel, and one morning while Father Louison was repairing his nets quietly in front of his hut, he heard himself being called:

“Hey! You, there, the Grand Trunk! Who allowed you to lay a hand on my boy?’’

“Your boy cruelly beat a dog that he could not drown, and I thought I was doing you a service by preventing him from martyring a poor animal who did not even defend himself.’’

“It was none of your business”, replied Rivet, “and I don’t know what keeps me from making you pay for the blows you gave my son straight away.’’

And the man raised his voice in a threatening tone, and some curious people had already gathered to find out the cause of the commotion.

“Sorry, my friend,” replied the old man quietly. “What I did, I did with good intentions, and you also know that I did no harm to your child.’’

“It does not matter. You weren’t allowed to touch him’’, and he held out his hand high towards the old fisherman who was quietly tying his net. The old man look up too late to parry the blow which struck him in the face, without, however, doing much harm.

Words cannot describe the transformation which took place in the countenance of Father Louison in response to this brutal affront. He straightened up to his full height, violently threw the net he was holding in both hands, and bounded like a panther on the ruffian who had just struck him without provocation.

His eyes flashed with anger, and before he could be stopped, he grabbed his opponent by the waist and lifted him up as he would have done with a child, above his head, and at the length of his long arms, he threw him with incredible violence on the sand of the shore, uttering a roar of a wild beast.

The poor devil, who had thought of attacking a helpless old man, had just awakened the anger and the power of Hercules. He fell unconscious, unable to get up or make any movement.

Father Louison considered him for a moment, but only one moment, and, rushing on him, picked him up again, advanced towards the waters of the river, held him for a moment suspended in the air and threw him forcefully on the wet sand hardened by the waves. The victim was already half-dead and crashed with a dull sound like that of a bag of grain dropped on the ground.

The spectators, who were becoming numerous, did not dare to intervene and timidly watched this tragic scene.

Before anyone could step in to stop, the old fisherman rushed again to Rivet, and this time holding the end of his arm, he ran into the water with the obvious intention of drowning him.

A clamor arose among the crowd:

“He’s going to drown him! He will drown him!’’

And, indeed, Father Louison continued to advance into the water, which was already lapping at his waist. Although no longer advancing as quickly as he had started, he continued until the water reached his armpits; then, swinging poor Rivet two or three times above his head, he plunged him into the river, to a depth where it would have been necessary to be a good swimmer to be able to regain the shore.

The old man then seemed to hesitate for a moment, as if to make sure that his victim had disappeared underwater, before returning to the shore in measured steps and locking himself in his miserable cabin, without any of the curious people who were there daring to raise their hands or even open their mouths to ask for mercy for the life of the unfortunate Rivet.

As soon as Father Louison had disappeared, however, they all rushed towards the canoes that were there, to fly to the rescue of the drowned man who had not yet appeared on the surface. But the emotion of the moment prevented rather than accelerated the movements of these men of good will, and poor Rivet would certainly have lost his life had some unexpected saviors not come to the rescue.

A cage [4] descended offshore with the current and a bark canoe containing two men was detached from it. It was only two or three acres from the shore where Father Louison had advanced into the river to precipitate his attacker. The two men in the boat had followed all the ups and downs of the drama, and when poor Rivet’s body reappeared on the water after a few minutes of immersion, they were able to seize him by his clothes and place him in their boat, to applause of the crowd that was still growing on the shore.

Two vigorous strokes of the two paddlers landed the canoe, and the inanimate body of poor Rivet was laid on the shore to await the arrival of the priest and the doctor who had been sent to see him.

It was not too soon, for the asphyxiation was almost complete, and it was necessary to, have recourse to all the means prescribed by science for the rescue of the drowned, in order to bring back a sign of life to the unfortunate Rivet whose wife and children had rushed to the scene and filled the air with their lamentations and their cries of despair.

The parish priest had taken the precaution of giving absolution in articulo mortis [5], but the physician declared before long that there was reason for hope, and the dying man was transported to his home, where he received visits and keen care from all of the village busybodies.

III

If it were true that Father Louison enjoyed the reputation of a peaceful and harmless man and that Rivet, on the contrary, passed for a grumpy and quarrelsome man, such a terrible revenge for a simple punch could not lack, nevertheless, to produce a general emotion in all the inhabitants of ‘L’.

The parish priest, the notary, the doctor and the other local notables met the same evening with the militia captain, who was at the same time the magistrate of the parish, to deliberate on what should be done in such serious circumstances.

The gentlemen decided to hold an investigation the next morning and to call Father Louison to appear before the magistrate, and to wait for the doctor to give a final opinion on the patient’s condition, which seemed to be improving sufficiently to rule out any notion of an imminent or even probably death.

The village bailiff was asked to inform the old fisherman that his appearance was requested the next morning at nine o’clock, in the public hall of the village where the preliminary investigation would be held, and this news, thrown in pasture to the good women, soon went around the fort, as we still say in our countryside.

Father Louison had not reappeared since he had locked himself in his cabin. So, it was not without a feeling of terror that the bailiff had come to knock on his door, in order to communicate to him the magistrate’s orders.

“Monsieur Louison! Monsieur Louison!’’ he said, in a low, trembling voice.

But to his surprise, the door opened immediately and the old man walked out quietly;

“How may I help you Jean- Thomas?’’

“The magistrate told me to inform you that he wanted to see you tomorrow morning in the public hall for … for …’’

“Very well, Jean-Thomas, tell the magistrate that I will be there when the time comes.’’

And he quietly closed the door as if nothing extraordinary had happened, and as if he had answered a customer who asked him for a bunch of eels or panfish.

IV

The next day, at the appointed hour, the public room was packed and the doctor first announced that Rivet’s condition was continuing to improve. A sigh of relief escaped from all chests and the investigation began.

Father Louison had been punctual at the magistrate’s order, but he was sitting alone in a corner, hunched over, elbows on his knees, and his head in both hands.

When the magistrate called, asking him to recount the events of the previous day, while telling him that he was not forced to incriminate himself, he got up quietly and recited, his eyes lowered, and in a voice heartbreaking with regret and shame, all that had happened, without forgetting the least incident. He ended with these words:

“I got carried away by an insurmountable fit of anger and I behaved like a brute and not like a Christian. I beg your pardon, Mr. Magistrate, I beg forgiveness of Rivet and his family and I beg forgiveness of the inhabitants of the village who witnessed the great scandal that I caused by my anger and by my brutality. I thank God for having spared Rivet’s life and I am ready to undergo the punishment I deserve. ’’

“It is fortunate for you, Father Louison,’’ replied the magistrate, “that Rivet’s life is not in danger, because I would have had to send you to prison. However, your evidence must be corroborated, so we will ask the travelers who saved Rivet to share what they saw and what they did during yesterday’s event.”

The elder of the travelers, a member of the parish who had been returning from a winter spent in the Gatineau logging camps, simply told the facts of the rescue and corroborated Father Louison’s testimony. His companion, who was also a man in his sixties, came forward to tell his story, when he found himself face to face with the accused, whom he had not yet seen. He looked him straight in the face, hesitated for a moment, then in a voice tinged with fear and astonishment, said:

“Louis Vanelet!”

Father Louison raised his head in an involuntary movement of terror and looked at the man who had just pronounced this name, unknown in the parish of ‘L’.

The eyes of the two men crisscrossed like two blades of steel shocked by the first clash of a swordfight, then lowered immediately, and the old raftsman recounted the rescue in which he had taken part and the drama which he had witnessed, without making any other allusion to this name which he had just thrown in the pasture to public curiosity.

It was evident that despite the painful events of the day before, the sympathies of the audience leaned towards Father Louison, and few aside from the magistrate paid much attention to the necessary statements of the witness and the accused. After all, we are naturally inclined to indulgence when it comes to our countryside inhabitants, and the investigation was promptly terminated by the magistrate, who simply ordered the old fisherman to return home, to go about his business, and to keep himself at the disposal of justice.

The crowd dispersed slowly and Father Louison returned to lock himself in his hut to escape the curious glances which followed him.

The magistrate, before leaving, approached the last witness and ordered him to come and see him, at his house, the same evening, at eight o’clock. He wanted to talk to him.

V

Faithful to the meeting which had been imposed on him, the old traveler found himself, at the appointed hour, in the presence of the judge, the parish priest and the notary who had met for the occasion.

He had some suspicions regarding the reason for this new kind of tribunal before which he had been called. So, he was not taken by surprise when he was asked point blank:

“You have known Father Louison for a long time and you gave him the name of Louis Vanelet this morning at the hearing.’’

“It is true, judge,” replied the traveler, without hesitation.

“Tell us then, where, when and how, you got to know him?’’

“Oh! It has been a long, long time. It was at the time of my first trip to Gatineau. We were working for the Gilmour [6], and Louis Vanelet and I were logging in the same camp. He was a good worker, a good hewer and a good chap. Everyone especially liked to hear him tell stories in the evening around the lazarette [7]. One day, a squad of workers arrived to share our site and there was one among the new arrivals who knew Vanelet and who came from the same parish as him, near Montreal. They barely greeted each other and it was evident that there had been tension between them. Nothing extraordinary happened to disturb the harmony, until one day when Vanelet came to me and asked me to be his witness in a boxing match he would have the next day with his co-parishioner. “We love,” he said to me, “the same girl in the country, and since we cannot both marry her, we want to settle the matter with a game of boxing.’’ The proposal seemed to me quite reasonable, because we fight willingly and for very small reasons in the logging camps. So I accepted, and the next morning, early in the morning, before working hours, the adversaries were face-to-face in a nearby clearing. The battle began fairly smoothly; but hardly had the first blows been struck before Vanelet was absolutely out of himself, in a fit of black fury. Stronger and more dexterous than his adversary, he dealt him terrible blows, under which the other crumpled as if hit by a club. I tried in vain, with the other witness, to intervene and put an end to the fight, but Vanelet, mad with rage and strong as a bull, continued to strike until his adversary, with swollen eyes and the bloody face, fell senseless and could not get up. Then Vanelet grabbed him and threw him at the end of his arms, threw him on the hardened and icy snow which covered the ground. The poor devil was unconscious and blood came out of his nose and his ears. Vanelet was about to rush to his victim again when we threw ourselves on him and it was with the greatest pain that we succeeded in preventing a murder. I had never seen a man so strong, in such terrible fury. He did, however, calm after a while and ran like crazy through the forest. My companion went to the timber camp to obtain a sled to transport the inanimate body of our comrade. Although it was February and we were in the middle of the forest, very far from any habitation, Louis Vanelet disappeared from the site. I saw him again yesterday for the first time since that memorable time, because none of us knew what had become of him. The poor man whom he had almost knocked out lingered for a long time between life and death and we brought him back, in the spring, in a pitiful state, to send him back to his family. I have learned since that he recovered and that he ended up marrying the one for whom he had almost sacrificed his life. ”

The magistrate, the parish priest and the notary, after having listened to this story carefully, consulted each other for a long time and finally decided that, in view of Father Louison’s irascible character, his terrible anger and his Herculean strength, it was necessary to make an example of him and bring him before the Criminal Court which sat in Sorel.

The bailiff would receive instructions to this effect.

VI

When the law enforcement official went the following morning to arrest Louis Vanelet, he found the cabin empty. During the night, the old man had disappeared, carrying his hunting and fishing gear in his canoe. No one had seen him leave and it was not known which direction he had taken.

A few days later, the captain of an ‘L’ boat said that during a strong gale from the northeast, he had encountered a long canoe floating on Lake St. Pierre, bobbing with the waves and winds.

He thought he recognized Father Louisin’s boat, but the canoe was empty and half full of water.

Footnotes:

[1] The Grand Trunk Railway, which operated in Quebec and Ontario, and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

[2] An Indian-style fishing net.

[3] A French water dog.

[4] Log raft.

[5] Latin for “the moment of death”.

[6] The Gilmour Lumber Company, a great Canadian timber company.

[7] The area surrounding the cockpit of a boat.

Leave a Reply