Legends of Prince Edward Island

“There’s a white lady walks along the brook just about this time of the night and wrings her hands and utters wailing cries. She appears when there is to be a death in the family. And the ghost of a little murdered child haunts the corner up by Idlewild; it creeps up behind you and lays its cold fingers on your hand- so. Oh, Marilla, it gives me a shudder to think of it. And there’s a headless man stalks up and down the path and skeletons glower at you between the boughs. Oh, Marilla, I wouldn’t go through the Haunted Wood after dark now for anything.”

So said Anne Shirley, the imaginative red-headed heroine of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s classic 1908 children’s novel Anne of Green Gables, of a particular spruce grove in Atlantic Canada. “Diana and I just imagined the wood was haunted…” the 12-year-old orphan confessed to her adoptive guardian, Marilla Cuthbert, Diana Barry being Anne’s dearest playmate and so-called ‘bosom friend’. “I don’t believe it in daylight. But after dark, Marilla, it’s different. That is when ghosts walk.”

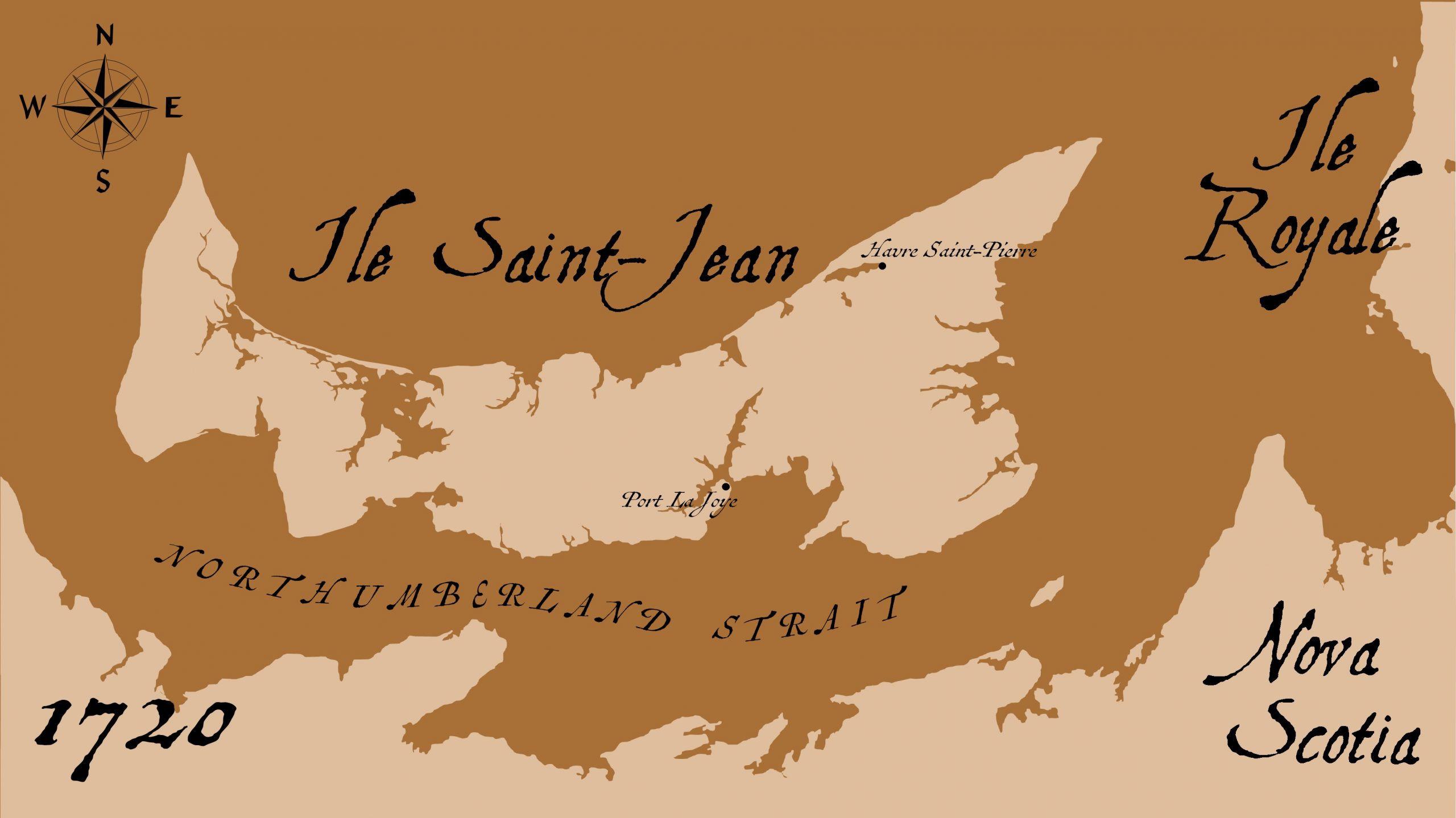

Anne’s ‘Haunted Wood’, as well as the proximate fictional town of Avonlea in which Anne of Green Gables is set, are based on real locations in north-central Prince Edward Island (PEI), Canada’s smallest province. Nestled in the southernmost crook of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, this enchanting crescent-shaped isle is separated from the southerly Maritime Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick by a strip of Atlantic Ocean called the Northumberland Strait. Known nationally for its preponderance of potatoes and ubiquitous red sandstone, the Island’s greatest claim to fame is undoubtedly Montgomery’s internationally-renowned novel and its four sequels, whose titular protagonist declared it “the prettiest place in the world.”

Although the preternatural nature of Avonlea’s Haunted Wood is admittedly the product of Anne’s fertile imagination, which the latter dreamed up for the purpose of injecting some romance into her prosaic surroundings, Canada’s island province is filled real mysterious locations pregnant with age-old legends which even Miss Shirley would be hard-pressed to improve upon. From haunted coves and mystical ponds to phantom lights and monsters of the deep; from chilling tales shared around the hearths of Scottish and Irish farmers to ancient traditions orated by the flickering light of Acadian and Mi’kmaq campfires; here are a few of the many colourful legends of Prince Edward Island.

The Battle of Pretty Stream

Long before canvas sails first appeared off Canadian shores, Prince Edward Island was the domain of the Mi’kmaq Indians, a semi-nomadic people who lived in seasonal villages, following the fish and game. The Mi’kmaq are said to have called the isle Abegweit, a word which means “Cradled Upon the Waves.” Much like Islanders today, PEI’s native inhabitants also referred to their insular abode simply as Minegoo, or “the Island”.

According to Island folklorist Frank Harold MacArthur in his 1966 book Legends of Prince Edward Island, ancient oral tradition has it that when Mi’kmaq braves first pulled their birch bark canoes onto PEI’s ruddy shores in mists of prehistory, having paddled out from their ancestral haunts on the mainland of what is now Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, they discovered that they were not the first intelligent beings to set foot thereon. Minegoo, they learned, had long since been settled by a race of tiny men and women with preternatural abilities, whom posterity remembers as the “Tweedlers”. Oral history has failed to record the details of the Mi’kmaq’s first encounter with the Tweedlers, recalling only that the relationship between the two races was violent from the start.

For many months following their relocation, PEI’s first Mi’kmaq settlers battled with the little people for the right to hunt and fish on Abegweit. The Tweedlers violently resisted the red men’s occupation at every opportunity, attacking any lone warriors who strayed too far from the main party, and stealing women and children from their wigwams in the night.

When the little people kidnapped the Mi’kmaq chief’s only son, the Indians held a powwow. After deliberating long into the night, the tribe’s elders and war chiefs decided that they must put every last Tweedler to the knife if they hoped to retain their foothold on Minegoo. Weapons in hand, they left the safety of the campfire and set out into the dawn twilight, determined to achieve their grim purpose.

The Mi’kmaq came upon the camp of their diminutive enemies at a place they called “Pretty Stream”. Another version of this tale in MacArthur’s book identifies Pretty Stream as a brook which runs through Kellow’s Hollow, a wooded area in what is now the town of Cornwall, located on the shores of the West River west of the capital city of Charlottetown. This author, with the help of Cornwall natives, has identified Kellow’s Hollow as the vale of Hyde Creek, a brook sandwiched between the parallel streets of Lacardy and Kellow Drive.

“Night and day the fighting went on for a period of three days,” MacArthur wrote of the subsequent battle between the Mi’kmaq and the Tweedlers. “No quarter was asked of either side and none was given. Women and children were slaughtered along with the warriors of both races, and finally, when the conflict had come to an end only a handful of redmen remained alive to view the bloody scene. The bodies of the slain lay all about the place. Even Pretty Stream was full of dead bodies while the water itself was dyed red.”

According to Mi’kmaq chief John Sark, from whom MacArthur heard the tale, the Battle of Pretty Stream was the bloodiest of its kind ever fought on Abegweit. “Tradition does not place a date for the fight,” MacArthur wrote, “nor do we know how many were killed in the engagement. What we do know, however, is that the Indians completely routed the enemy. Those fortunate enough to escape at the time, later were rounded up, put aboard tiny boats, and set adrift in the Gulf Stream. Tradition says they were all lost in a great storm that followed their expulsion.”

Ever since the Battle of Pretty Stream, Kellow’s Hollow is said to have possessed an enchanted atmosphere, almost as if the blood of little warriors who fell there imbued the wooded vale with the same mystical quality for which the Tweedlers were noted. Indeed, the ancient battlefield serves as the setting of many more mysterious tales in MacArthur’s book and other collections of Island folklore, such as the story of a haunted hollow tree which once stood at the edge of the old bridge over Hyde Creek, and tales of mysterious blood curdling shrieks which emanate from the Hollow at night, startling pedestrians who dare to pass over the bridge in the dark.

If other Island legends are to be believed, the echo of preternatural power at the site of their last stand may not be the only legacy the Tweedlers bequeathed PEI. Despite the assurances of native tradition, generations of settlers have told stories about little fairy-like people spotted fleetingly from time to time in lonely groves and secluded coves throughout the Island, hinting at the possibility that the Mi’kmaq of antiquity may not have exterminated their little neighbours as thoroughly as tradition contends.

Discovery

With the exception of Norse explorers, who discovered and colonized parts of Atlantic Canada in the Middle Ages, the first white men known to have set eyes on Canadian soil were sailors under the direction of Giovanni Caboto, or John Cabot, an Italian navigator whom English King Henry VII commissioned with finding a westerly shipping route to the Orient. On June 24th, 1497, the feast day of St. John the Baptist, Cabot and his crew got their first glimpse of the American continent and made landfall on the spot. Although many historians agree that Cabot and his men probably disembarked at Cape Bonavista, on the eastern shores of Newfoundland, others argue that he more likely made landfall on southerly Cape Breton Island, off the northern coast of the Nova Scotian peninsula. Later that same day, Cabot and his men disembarked on a nearby island, which they named l’Ile de Saint Jean, or Saint John’s Island, in honour of the holy martyr whose birthday marked the occasion. A handful of maverick scholars, supposing that Cabot’s first landfall was Cape Breton Island, have suggested that this second island may have been PEI.

For thirty seven years after Cabot’s discovery, Abegweit remained hidden from European eyes, bypassed as it was by crews of Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano and Portuguese cartographer Estevao Gomes, who sailed up the Atlantic seaboard in 1524 on behalf of France and the Habsburg Empire, respectively. In 1534, Breton explorer Jacques Cartier made his own trans-Atlantic voyage at the request of Verrazzano’s benefactor, King Francis I of France. That spring and summer, he thoroughly explored the coast of Newfoundland and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, becoming the first white man (with the possible exception of John Cabot) to lay eyes on Prince Edward Island on June 30th of that year. In his ship’s log, he described the land of PEI as “the fairest that it may be possible to see,” praising its level nature and the quality of its trees, meadows, and wild fruit. Despite the considerable time he spent ashore, investigating the island’s flora, fauna, and native inhabitants, Cartier failed to discover the Northumberland Strait and assumed that PEI was part of the mainland.

It would be a full century after Cartier’s voyage before PEI was formally recognized as the island it is. In his 1634 map of Atlantic Canada, French explorer Samuel de Champlain drew the isle in its proper location in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Champlain labelled the island Ile Saint-Jean, or Saint John Island, apparently naming it after the mysterious second isle discovered by John Cabot back in 1497, and for a hundred and twenty-four years, the name stuck.

Acadian Settlement

The first white men to build their homes on Ile Saint-Jean were independent Breton, Basque, and Portuguese fishermen, who required home ports and curing facilities by which to preserve the cod they caught in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. With the exception of these transient fishing communities, and a temporary influx of frightened French settlers following the British capture of the Nova Scotian peninsula in the War of Spanish Succession, Ile Saint-Jean remained the almost exclusive domain of the Mi’kmaq until 1720, when a Norman nobleman named Louis-Hyacinthe de Castel, Compte de Saint-Pierre, was granted royal licence to establish a French colony there.

That year, the Compte de Saint-Pierre founded two settlements on the Island. The first was the fishing community of Havre Saint Pierre, or St. Peter’s Harbour, which lay at the innermost end of St. Peter’s Bay, on the island’s northeastern shore. The second was southwesterly Port La Joye, the little colony’s new administrative capital, located on the western shores of the mouth of what is now Charlottetown Harbour.

By 1721, nineteen French families comprising a total of one hundred souls had taken up residence on Ile Saint-Jean alongside the native Mi’kmaq. Some of these immigrants came directly from France, while others emigrated from nearby Acadia, a former French colony comprising parts of Maine, New Brunswick, and peninsular Nova Scotia, which had become British possessions in 1713 during the War of Spanish Succession. Ever since, the French settlers of Ile Saint-Jean have been referred to as ‘Acadians’.

The Island’s Acadian population grew steadily until 1724, when the colonization project fell through, prompting nearly all of Ile Saint-Jean’s white residents to return to France or Ile Royale, the latter being the name of the French colony on Cape Breton Island. A second project was launched in 1731, and throughout that decade, French settlers once again trickled onto the island, some taking up the net of the fisherman and others settling down with the plough of the farmer. Nearly all Acadian settlements on Ile Saint-Jean- including the burgeoning communities of East Point, Savage Harbour, and Tracadie- were located on the eastern half of the Island, or ‘Down East’, as Islanders refer to the region today, its occidental counterpart being the more wild country ‘Up West’.

The Mineotta Stone

Due in part to the successful efforts of French Jesuit missionaries throughout the Maritimes, Ile Saint-Jean’s Gallic inhabitants enjoyed a friendly relationship with their Mi’kmaq neighbours from the very start. In addition to an amicable trading partnership, they entered into a formal military pact called the ‘Grand Alliance,’ in which both nations agreed to make common cause against their hereditary enemies, the English and their native allies.

The Acadian-Mi’kmaq harmony that reigned over Ile Saint-Jean in the early-mid 18th Century gave rise to several fascinating legends, the most famous of which is a two part tale that, like all great oral traditions, has a number of different variations. Despite their discrepancies, nearly every version agrees that the first part of the story began during the reign of the Mi’kmaq, when red men enjoyed sole occupancy of the Island they called Abegweit.

The tale begins on the shores of a mysterious lake, the identity of which not all storytellers are in agreement. One of arguably two variations of this legend which appears in Frank Harold MacArthur’s book indirectly designates this body of water O’Keefes Lake, a freshwater oval off the PEI Highway 5 measuring one kilometer from end to end, located in the middle of forest and farmland near the centre of the island’s easternmost third. The other of MacArthur’s stories identifies this aquatic habitat as a pond near either Malpeque Bay, a community situated on the eastern shores of its salty namesake, near the island’s north-central shore, or as a pool near Kellow’s Hollow, the site of the ancient battle between the Mi’kmaq and the Tweedlers. Island storyteller Sterling Ramsay, in his 1973 book Folklore: Prince Edward Island, contends that the ‘pond’ is really a brook called ‘La Grande Source’, located near St. Peter’s Bay. And a well-researched 1983 children’s book called The Witch of Port LaJoye, written by Joyce Barkhouse and illustrated by Daphne Irving, gives this body of water the sinister and obsolete appellation of Minnewauken, or ‘Devil’s Lake,’ and places it alternately at Scales Pond, about 9 miles southeast of the city of Summerside; or at Rocky Point, just northwest of Port La Joye. Whatever the case, this pool was said to have once been home to a dangerous preternatural monster, most often portrayed as giant aquatic serpent. In one of MacArthur’s versions, the monster was described as a silvery twenty-foot-long amphibian with fins, a hooked beak, a large hump on its back, and a single eye as large as a saucer, whose den was a deep subterranean tunnel which connected the lake with the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

One day, a Mi’kmaq chief named Kiotsaton (whom MacArthur called ‘Chief Sunlight’) wandered near the shores of this secluded lake. Kiotsaton had just lost his wife to disease and, in his misery, had left his tribe to grieve with his teenage son, Kitpou (whom MacArthur named ‘Petre’, and Ramsay ‘Sunfells’), and his beautiful daughter, Mineotta (sometimes spelled ‘Mineota’). This quiet hideaway seemed the perfect place to vent their sorrow, and so the chief and his two children pitched their wigwam on the lake’s shore.

That night, long after his children had gone to bed, Kiotsaton remained seated by the smouldering remains of his campfire, gazing mournfully into the embers. So engrossed was he in melancholy that he failed to notice the stranger who materialized from the darkness and took a seat beside him.

“Kwa!” the stranger said, startling Kiotsaton from his sorrowful reverie.

“Kwa!” the chief replied, returning the customary Mi’kmaq salutation. “Who are you and what do you want?”

The stranger informed the astonished Kiotsaton that he was Glooscap, the legendary, benevolent, superhuman ancestor of the Mi’kmaq. Before the widower had a chance to respond to this extraordinary introduction, Glooscap advised the chief of the evil spirit that dwelled in the lake, and warned him to never venture out onto the water lest he incur the monster’s wrath. With that, the stranger vanished like mist into the darkness.

In spite of the danger, Kiotsaton was determined not to be driven from his new lakeside camp. The following morning, he told his children of Glooscap’s warning, and made them promise to never take their canoe out onto the lake.

For many moons, the family of three lived happily on the shores of the haunted lake, hunting and foraging in the surrounding woods and fishing in a nearby stream. Never once did they disturb the water of the lake itself, and never once did they see any sign of the lake’s legendary inmate.

One day, while her father and brother were out hunting, Mineotta went to gather berries by the lake’s shore. While picking from a particular branch which dangled precariously out over the water, she saw her beautiful reflection in the lake’s surface and bent down to admire it. As she did so, her long hair brushed the water, creating rings of ripples which marred the lake’s glassy stillness.

Almost immediately, a violent thrashing erupted from the middle of the lake. Startled, Mineotta looked up to see a huge serpentine trunk undulating near the water’s surface, creating a rapidly growing whirlpool. When the monster began to move toward her, Mineotta dropped her basket and fled for the safety of the forest.

That evening, a proud Kiotsaton and a triumphant Kitpou returned to the wigwam with a huge caribou- Kitpou’s first kill. Mineotta, who had summoned the courage to return to the wigwam when her father and brother announced their arrival, began to process the carcass in penitent silence.

Later that night, after the three had eaten their fill of fresh boiled caribou, Mineotta confessed her blunder and described the giant snake-like monster she had seen in the middle of the lake. Kitpou, his pride swollen by his fresh achievement, scoffed at his sister’s tale and dismissed it as the fanciful imaginings of a frightened little girl. Old Kiotsaton, on the other hand, admonished his son for his impiety and reminded him of Glooscap’s warning.

The three Mi’kmaq spent the following days in blissful indolence, lounging by the lakeside and subsisting off dried strips of caribou meat that Mineotta had prepared. When the time came for another hunt, Kiotsaton and Kitpou proceeded up their favourite game trail. They had not gone far, however, when the old chief twisted his ankle, rendering him temporarily useless as a hunter. Eager to prove his worth in his father’s stead, Kitpou volunteered to finish the hunt alone, and set out into the wilderness as Kiotsaton limped back to camp.

In no time, the young hunter brought down a fat doe, the choice cuts of which he packed into a buckskin sack and carried back towards camp. Kitpou’s hunting trip had taken him into the wilderness on the far side of the lake. When he returned to the lake’s shore, he saw his father and sister sitting on the opposite shore, chatting merrily as they boiled trout in a birch bark basket.

Kitpou knew from experience how long it would take to haul his fresh venison all the way through the woods along the lake’s shore. Finding his father’s abandoned canoe in the brush nearby, he decided to take the forbidden shortcut across the lake. For a brief spell, his father’s warning and his sister’s incredible tale stayed his steps, but the young hunter quickly brushed aside such womanly fears and guided the canoe out onto the lake.

When they spotted his distant form paddling towards them, Kiotsaton and Mineotta pleaded for Kitpou to turn his canoe around before it was too late. Ignoring their frantic entreaties, the hunter boldly pressed on.

When Kitpou had reached the middle of the lake, a great disturbance suddenly upset the water beneath him. Kiotsaton and Mineotta watched in helpless horror as a strong green limb emerged from the water, wrapped itself around Kitpou’s canoe, and pulled the young hunter and his craft to the bottom of the lake. And as quickly as it had begun, all was quiet again.

Enraged, Kiotsaton ran to his wigwam, seized his bow and quiver, and returned to the lakeshore. Then, much to Mineotta’s consternation, he began throwing stones into the water, defying the monster to emerge once again from the safety of its watery lair. Once again, a whirlpool formed in the middle of the lake, in the midst of which could be seen the serpent-like body of the lake’s monstrous inmate, thrashing about like a rattlesnake dragged from its den. Kiotsaton, his blood boiling with fury, knocked an arrow to his bowstring, drew it back to his ear, and sent the bone-shod missile hurtling into the seething mass. His arrow evidently hit its mark, for the lake began to froth and toss about with unimaginable violence, hurling sheets of water onto the shore in ever larger waves.

It soon became clear to Kiotsaton and Mineotta that the lake was rising. Left with little alternative, the father and daughter abandoned their wigwam and fled to higher ground. When they reached the top of a nearby hill, the booming voice of Glooscap suddenly erupted from the clouds, admonishing them for angering the spirit of the lake and informing them that, as a consequence of their actions, the entire island would soon be covered with water, and all the Mi’kmaq who called Minegoo their home would drown.

“What can we do?” inquired the old chief, desperate to avert his people’s sickening fate. The great Mi’kmaq ancestor informed Kiotsaton that the impending flood could only be prevented if Mineotta sacrificed herself to the spirit of the lake. The chief staunchly refused to give up his last living child, but Mineotta, having heard Glooscap’s words, sorrowfully slipped from her father’s grasp and waded into the water. Once again the waves roiled, and once again the serpent made his ghastly appearance. Before the stricken chief had the chance to shoot another arrow, beautiful Mineotta disappeared beneath the waves. Immediately, the water level began to fall. Before long, the lake resumed its regular appearance, and the water spirit, appeased, retreated to its subsurficial abode.

For many hours, Kiotsaton lay on the hillside like a corpse, utterly devastated. No sooner had he resolved to remain in his prone position until death overtook him than the sonorous voice of Glooscap once again boomed from the heavens. The ancient Mi’kmaq ancestor informed the chief that, in honour of Mineotta’s sacrifice, a special stone would appear at the edge of the brook which fed the lake, not far from his lodge. This conical, copper-coloured concretion would heal anyone of Mi’kmaq blood who touched it from illness and injury, but was never to be used on a person of foreign heritage. Thenceforth, the medicine rock would be known as the Mineotta Stone.

Kiotsaton descended the hill and found the cone-shaped stone just where Glooscap said it would be. For the rest of his life, he lived by the shores of the lake, curing all those who came to him through the healing power of his daughter’s stone, by which he earned the reputation of a powerful medicine man. When old age and infirmity began to overtake him, and he felt his own death fast approaching, Kiotsaton dropped the Mineotta Stone into the deepest part of the stream, where it remained for generations.

The Witch of Port La Joye

The second half of this multifarious folktale, according to some of its many renditions, takes place generations after the tragedy of Princess Mineotta, in the year 1722, two years after the establishments of Havre Saint-Pierre and Port La Joye, when French and Acadian settlers first began to take up permanent residence on Ile Saint-Jean. Among the first residents of Port La Joye, so the story goes, were a mysterious Basque widow named Madame Grandville and her beautiful daughter, Marie. Judging from the quality of the furnishings and clothing they brought with them onto the Island, the mother and daughter were evidently quite wealthy, although none of their new European neighbours knew the source of their affluence. Rumours began to fly that Madame Grandville’s late husband was an English buccaneer who had been hanged for piracy on a London gallows, who had buried a cache of ill-gotten loot in the Caribbean sometime prior to his untimely demise.

Thoroughly imbued with the proud and independent character for which their people were famed, Madame and Marie Grandville never quite fit in with their Gallic neighbours. On the contrary, the Basque women found kindred spirits in the wild and carefree Mi’kmaq, who made occasional visits to the village to trade, and soon began to spend more time in the camps of their red trading partners than at the hearths of their white compatriots. By the autumn of 1723, it was not unusual for the French and Acadian settlers of Port La Joye to catch Madame Grandville out in the woods with the old Mi’kmaq wives picking roots and herbs, or spot Marie’s graceful form silhouetted against the evening twilight in the midst of an Indian camp, dancing to the throb of a moose skin drum.

Marie caught the eye of a prominent Mi’kmaq brave, the son of a local chief, and before the year was out, the unconventional couple announced their intention to marry. The surprise engagement was a shock to the sensibilities of both the Port La Joye settlers and the native Indians, both of whom would have preferred to see these juvenile paragons pared with partners of their own ethnicities. Despite the many objections raised by members of their respective nations, however, the star-crossed lovers resolved to stay true to their pledge.

In preparation for the wedding, Madame Grandville decided to return to her former place of residence to retrieve a suitable dowry for the Mi’kmaq chief- perhaps, some said, the last of her late husband’s buried treasure. Marie would not allow her mother to make such a dangerous journey alone, and so she accompanied her in a birch-bark canoe from the Mi’kmaq camp down one of the three great rivers that feed Charlottetown Harbour, intending to flag down the next seagoing ship that passed by.

The Grandvilles never made it out of the harbour. Through some mysterious accident, which many attributed to the work of saboteurs indignant at the prospect of the impending interracial marriage, the women’s boat capsized somewhere near Port La Joye. The apparently-lifeless bodies of Madame and Marie Granville were found by French settlers, washed ashore south of the remains of their wrecked canoe. Madame Granville proved to have drowned in the harbour’s frigid waters, but Marie, though semi-conscious, stubbornly clung to life. The settlers did everything in their power to revive their beautiful Basque belle, as did local Mi’kmaq medicine men when the Acadians’ ministrations proved fruitless, but nothing seemed to ease Marie away from the mortal brink on which she so precariously teetered.

Finally, at the insistence of Marie’s betrothed, the chief of the local Mi’kmaq band had the girl packed onto a litter and carried to the site of the Mineotta Stone. Then, to the utter dismay of his tribesmen, he broke Glooscap’s ancient dictum and used his people’s beloved treasure to heal his daughter-in-law, a woman of foreign blood. Miraculously, the stone brought Marie back to the land of the living, but no sooner had she opened her eyes than the ancient Mineotta Stone crumbled to dust.

Despite the tragic death of her mother and her inability to secure a dowry, Marie was married to her betrothed as planned, in the custom of the Mi’kmaq. At the height of the wedding feast, when it seemed that all grudges had been laid to rest and all hatchets buried, a stray arrow flew from the throng of matrimonial revelers and struck Marie’s husband in the heart, killing him instantly. For many of the wedding guests, the fate of the chief’s son was just punishment for his violation of sacred tribal tradition, which led to the loss of their most precious artifact, and so the murderer went unindicted.

Marie lived out the rest of her days as a recluse on the outskirts of Port La Joye, welcomed by neither her husband’s people nor her own kith and kin. According to one version of this tragic legend, she was later accused of witchcraft by residents of the frontier settlement and was burned at the stake for her heresy near the site of the Blockhouse Point Lighthouse, not far from Port La Joye. Legend says that Marie sang a haunting Basque melody as the flames licked her legs, a faint echo of which can still be heard from time to time on the rocky point where she met her tragic end.

King George’s War

The fragile French colony on Ile Saint-Jean was born in the midst of a 30-year spell of peace, during which the various British and French colonies in Atlantic America maintained a shaky but bloodless status quo. In the mid-1740s, however, when the third great European war to hit the American continent spilled across the Atlantic, the little island colony was drawn into the fray.

The so-called War of Austrian Succession began in 1740, when Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, the last of the powerful Viennese Habsburg line, died after eating poisonous mushrooms on a hunting trip without first having produced a male heir to succeed him. Allies of the Habsburg family fought to place Charles’ eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, on the vacant imperial throne, while France and its equally-powerful House of Bourbon, citing an ancient Frankish law which excluded women from imperial succession, contested Maria Theresa’s claim. In 1743, the German-born King George II of Great Britain threw in his lot with the Habsburgs on account of an age-old alliance between that family and his own, and the following year, France declared war on Great Britain, plunging North America into intercolonial conflict for the second time that century.

In 1745, the British launched an assault on the Fortress of Louisbourg, a great French stronghold which had stood on the coast of Ile Royale, in various stages of construction, since 1720. While the siege was underway, the crew of a single British warship attacked an Acadian settlement at the eastern end of Ile Saint-Jean called Trois Rivieres. The British met with no resistance and burned the village to the ground. Their minor victory complete, the redcoats sailed around the Island and up Charlottetown Harbour to the meagrely-defended Port La Joye, which they treated similarly. They hounded the retreating French defenders up what is now the Hillsborough River before being driven back to their boats by local Acadian settlers and Mi’kmaq warriors drawn by the rattle of musketry.

In July 1746, British and French troops clashed a second time at Port La Joye. Earlier that summer, the British had taken up residence in the seaside settlement, which had long since been abandoned by the French, from which they began to appropriate cattle from local Acadian settlers in accordance with a non-aggression pact they had made after their skirmish the previous year. During one such operation on July 11th, a British infantry regiment was caught unarmed in a field outside Port La Joye by a combined force of French-Canadian militiamen and Mi’kmaq warriors. The attackers killed dozens of Englishmen in the ensuing massacre – the bloodiest of its kind ever perpetrated on the Island, with the possible exception of the Tweedlers’ last stand.

The Acadian Expulsion

Nearly a decade later, in 1754, the opening engagements of what would become the fourth, final, and largest of North America’s intercolonial wars broke out when British and French forces clashed on disputed territory in what was once considered French Louisiana. Throughout the ensuing conflict, which would eventually escalate into what some historians consider the first truly global war, many Acadian settlers in British-owned peninsular Nova Scotia assisted the French by maintaining supply lines to Louisbourg, that great Gallic stronghold having been restored to its mother country in the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. Some patriotic Nova Scotian Acadians went so far as to take up arms against the British themselves, banding together into ragtag militias. In a brutal attempt to quash this internal threat, the British Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, began to forcibly deport all Acadian families from Nova Scotia to France or New England en masse, making no effort to distinguish true partisans from friendly or neutral settlers. Many of these Acadian exiles later resettled in Louisiana, forming the people known today as Cajuns. In this tragic chapter of Canadian history, called the Expulsion of the Acadians, or Le Grand Derangement, thousands of settlers lost their lives due to disease, starvation, and shipwreck during their forced exodus from the land from which they took their name.

The North Atlantic theatre of the so-called Seven Years’ War culminated with Britain’s second and final capture of Louisbourg in 1758. The articles of the bastion’s capitulation stipulated that the entirety of Ile Royale be surrendered to King George II. As Ile Saint-Jean, at that time, was a subsidiary of the Cape Breton colony, it, too, became Anglo-Saxon territory by right of conquest.

In accordance with Lieutenant Governor Lawrence’s heavy-handed means of eliminating the Acadian threat from British territory in the Atlantic Northeast, Scottish officer Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Andrew Rollo was appointed the thankless task of sailing to Ile Saint-Jean and not only rounding up and deporting all the Acadian settlers who called the Island their home- a significant percentage of whom had relocated there from Nova Scotia throughout the previous decade- but also laying waste to their settlements, crops, and livestock. Some historians consider this particular wave of deportation especially egregious since the Acadians of Ile Saint-Jean, as a whole, remained neutral throughout the entirety of the Seven Years’ War in honest accordance with the non-aggression pact they made with the British back in 1745. Although Lord Rollo carried out his orders to the best of his abilities, a number of Acadians who had settled on the more remote corners of the island escaped the fate of their more centrally-situated compatriots by hiding in the woods until the British departed. Many descendants of these wily settlers call the Island home today.

Although not nearly as well-known as its Nova Scotian counterpart, the Acadian exile from Ile Saint-Jean was relatively more disastrous, resulting in the largest percentage of deportee deaths of all the Acadian expulsion campaigns. Of the seven ships that left Ile Saint-Jean with Acadian exiles bound for France, two sank in the North Atlantic and a third ran aground in the Azores, resulting in the combined loss of about 950 souls.

The Phantom Church of St. John

This dark period of PEI history is associated with several intriguing legends, two of which revolve around the hasty preparations the Acadians made on the Island prior to their deportation. According to one oral tradition which appears in Ramsay’s book, on the evening of their scheduled departure, the Acadians at Port La Joie- which the British renamed ‘Fort Amherst’ in honour of Jeffrey Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America- congregated in the local Church of St. John the Evangelist to recite the Litany of the Saints, the latter being a Catholic prayer in which various angels, saints, and the Virgin Mary are petitioned to intercede with God on the supplicants’ behalf. In the middle of the service, Lord Rollo himself burst through the church doors and ordered the congregation to head to the barracks the following morning for their embarkation. His message delivered, the lieutenant-colonel promptly broke up the assemblage.

Although the wooden frame of the Church of St. John has long since disappeared from the grassy slope at Fort Amherst, perhaps having been put to the torch with other buildings in that bygone capital of Ile Saint-Jean, some say that a ghostly image of the old chapel materializes in the evening from time to time on the spot at which it once stood, appearing just as it did on the night on which the Acadians’ final prayer was so irreverently curtailed. Witnesses claiming to have seen this apparition reported glimpsing lit tapers through the church’s glowing windows, and hearing the words “ora pro nobis”, or “pray for us,” uttered in unison by a phantom congregation, that phrase being the Latin response to each of the priest’s supplications in the Litany of the Saints.

The Hunchback of Point Prim

Another eerie tale associated with PEI’s Acadian Expulsion is set on Point Prim, a long, narrow peninsula forming the southeasterly lip of Hillsborough Bay on the island’s southeastern shore. According to Ramsay, who heard the story from an elderly woman who had lived in the area her whole life, the Point was once the site of an Acadian homestead belonging to an old hunchbacked farmer, who lived there with his wife and three children. In 1758, when it became clear that the Acadians of Ile Saint-Jean would be deported like their Nova Scotian counterparts, the homesteader buried his most valuable treasures beneath a particular pine tree on his property, fully intending to return to the Island in the future to dig them up.

When the British finally came to take them away, the farmer and his family were loaded onto the Violet, one of the three aforementioned deportation ships to meet a sticky end in the Atlantic. On November 12th, 1758, while en route to France, the Violet was beset by a ferocious gale and sank with all hands, sending 400 settlers and sailors to their untimely graves at the bottom of the sea.

Legend has it that the ghost of the drowned farmer returns to Point Prim on occasion to search for his buried treasure. Every once in a while, visitors to the Point Prim Lighthouse report hearing the mysterious scraping of a shovel emanating from the woods which fringe the shoreline. Some even claim to have seen the stooped apparition of the old hunchback himself, his face bearing an unusual nose marred by a deep scar extending to his ear, shuffling down the shore with a strange hand-made shovel carried over one shoulder.

The Fairies of Cape Wolfe

In the autumn of 1759, one year after Lord Rollo’s infamous Ile Saint-Jean Campaign, Major General James Wolfe, the second highest-ranking commander of British forces in North America, prepared to launch an assault on Quebec City, the capital of French Canada, by way of the St. Lawrence River. On his way from Louisbourg to this so-called Battle of the Plains of Abraham- the defining struggle for Quebec City in which Wolfe would gain a decisive British victory but lose his life in the process- the general is said to have stopped at a point of land near Ile Saint-Jean’s westernmost end. This beach would later be named Cape Wolfe in his honour.

According to a story in MacArthur’s book, at the time of the general’s visit, Cape Wolfe was home to a man named John French and his mistress, Janet Daisy- apparently, among the first Anglo-Saxon settlers to take up residence on the Island in the wake of its British conquest. The lonely couple had no close neighbours save for the strange and elusive occupants of a tumbledown shack about a half mile up the coast. This cabin, incidentally, was once the home of an Acadian family whose members all perished from some mysterious and terrible disease. When the last member of that family died, the shack was left to rot where it stood, locals pronouncing it haunted and unlucky. For most of the year, the cabin stood desolate and abandoned, the wind whistling through gaps between the cracked and graying logs that comprised its walls. On two particular evenings every year, however, the haunted house was invaded by mysterious revelers who played strange music and danced late into the night.

John French and Janet Daisy never actually saw the shack’s transient residents, but observed that on the May’s Eve (the last night of April), and on Halloween, the windows of the old cabin would glow merrily, and strange but cheerful music would issue from within. Those two dates being the supposed holidays of fairies, according to Celtic and Anglo-Saxon tradition, John and Janet could only assume that the shack was the occasional abode of little people- perhaps the descendants of the legendary Tweedlers whom the Mi’kmaq battled on the Island long ago.

John was discontented with his lot in life, and often expressed a desire to leave the world of men behind for the merry and carefree life of the fairies. One Halloween, after a particularly heated argument with Janet, he stormed out of his house and took a walk down the beach, in the direction of the haunted shack. As he neared the gloomy structure, he saw its windows aglow with lantern light, and heard the sound of tiny feet pattering on the wooden floorboards to the rhythm of an enchanting tune, punctuated by silvery laughter and joyful chatter. Without a second thought, John made up his mind to join the party, and boldly strode through the cabin door.

“About a score of little people were dancing to the music of flutes and fiddles,” MacArthur wrote, “while others stood about talking and drinking nectar from tiny silver mugs, no larger than thimbles.” The little people welcomed John into their midst and invited him to join in the merriment.

Meanwhile, back in her own cabin a half mile down the beach, Janet was beginning to get worried. She recalled John’s wistful talk about the fairies and, recognizing that it was presently one of the few nights of the year on which the fairies were said to be especially active, feared that her master might make good on his threat to join the little people and leave mankind behind.

When John returned home that night, Janet was dismayed to find that he had shrunk to the size of a small child- a consequence of his night of revelry with the fairies, and a change which John heartily welcomed. “Tradition tells us that after these startling events,” MacArthur concluded, “Janet returned to her own folk, while John went to live with the fairies…”

The White Lady of Holland Cove

In the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War, with the 1763 signing of the Treaty of Paris, nearly every French holding in the Atlantic Northeast was handed over to Britain, making that great island superpower the undisputed sovereign of the eastern half of the continent for the first time in history. In an attempt to better acquaint themselves with their new territories of Ile Royale and Ile Saint-Jean- now called Cape Breton Island and the Island of St. John, respectively – British authorities decided to formally survey them and divide them into counties. For this task, they appointed a Dutchman named Samuel Johannes Holland, an artillery engineer and veteran of the recent war who had applied for just such a job in London.

Holland arrived on the Island of St. John in early October 1764 and established a base camp on the western lip of Charlottetown Harbour, at a place he dubbed ‘Observation Point’. This natural harbour, located about a kilometre south of Fort Amherst, is known today as ‘Holland Cove’. Holland’s men built a house on the grassy elevation overlooking the beach, in which the surveyor stayed with his pregnant common-law wife, a 24-year-old French-Canadian woman named Marie-Joseph Rollet. That fall and winter, Holland and his crew surveyed the entire island and divided it into three counties and 66 Lots which are still recognized today.

The surveyor’s tenancy at Holland Cove is associated with an eerie ghost story which, like most of PEI’s best legends, has several different versions. The tale first appeared in print in 1896, in Volume VII of the Canadian Magazine, under the title, “The Legend of Holland Cove,” by F. Gerald. Harry Holman, PEI’s former Chief Archivist, in an article on his blog Sailstrait, tentatively identified the piece’s pseudonymous author as Judge Rowan Robert Fitzgerald, a prominent Island justice who died in 1921.

According to this version of the story, during his time on the Island of St. John, Samuel Holland took on a mistress – a tall, beautiful woman named Racine, who boasted both Acadian and Mi’kmaq heritage. One night in the winter of 1764, Racine ventured out onto the ice of Charlottetown Harbour, hoping to intercept her lover on his way home from one of his surveying expeditions. Not far from Holland Cove, she fell through thin ice and disappeared.

More than a decade later, on July 14th, 1776, members of Holland’s crew slept in the surveyor’s old cabin at Holland Cove. At the stroke of midnight, when the tide was high, one of the crewmen inside the house heard a woman’s voice emanating from the surveyor’s vacant bedchamber. Suspecting that an intruder had entered, he peered into the room and found a tall woman in a white dress, dripping with seawater, perched at the edge of Holland’s old armchair, chatting merrily as if in conversation with the chair’s invisible occupant. Apparently recognizing that she was being watched, the woman turned her head towards the newcomer and glared at him before gliding out of the house and onto the cove, leaving a trail of seawater on the wooden floorboards behind her. She then proceeded out onto the water, whereupon she let out a blood-curdling shriek and vanished. Knowing the tragic story of Holland’s mistress, the soldier assumed that the apparition was the ghost of Racine, returned to Holland Cove to search for her paramour.

The tale goes on to declare that, every year on the night of July 14th, if the tide happens to be high, the ghost of Holland’s mistress will appear at the site at which Holland’s cabin once stood, descend the cliffs that front Holland Cove, venture out onto the water, and vanish into the darkness. The apparition makes its appearance on July 14th, the piece contends, because that date was not only Racine’s birthday, but also the day on which the unfortunate woman first met Samuel Holland.

Historian Harry Holman thoroughly dowsed this ghost story with cold water in a scathing 2019 article on his blog Sailstrait. In that piece, the former PEI Chief Archivist argued that Samuel Holland, his official duties notwithstanding, could not practically have kept a mistress on the Island since he shared his house with his pregnant common-law wife, Marie-Joseph; that Holland could not have met Racine on any July 14th, since his surveying operation on the Island did not extend into the summer; and that his crew departed the island more than a decade before the summer of 1776, in which the second half of the story takes place. Holman points out similar anachronisms in Charles M. Skinner’s retelling of the legend in his 1898 book Myths and Legends Beyond Our Borders, and in another version of the tale which appeared in a May 1935 issue of the Charlottetown Guardian.

Despite his commendable efforts, Holman, in this author’s opinion, has not entirely succeeded in putting this ghost story to bed. It is certainly possible that the legend of Holland’s mistress might have been invented in an attempt to explain the appearance of an otherwise real phantom. With that idea in mind, this author, who fortuitously happened to be visiting Prince Edward Island for a wedding that very week, made the long drive out to Holland Cove on the night of July 14th, 2022. After taking a few wrong turns, he managed to pull up to the beach a few minutes before midnight. When the witching hour struck, however, the only ghost he saw was the flickering of a dead campfire which an errant gust of wind blew back to life. After lingering in the area for some time, seeing nothing more spectacular than the play of the moonlight and the beam of a nearby lighthouse on the waves, he began the return journey, convinced that if the white lady of Holland Cove had ever made summer appearances on the shore, she had since abandoned her annual custom. It was only upon being overtaken by a more astute ghost hunter on the PEI Highway 19 that he realized that he had very clumsily made his vigil on the wrong beach, at the cliffs beside the Blockhouse Point Lighthouse a mere half mile northeast of Holland Cove. Like Holman, this author has similarly failed in his attempt to debunk the ghost story of Holland Cove, and for him, at least, the legend lives on.

The Ghosts of Brudenell Island

In the late 1760s and the early 1770s, in the wake of the British conquest, settlers from Scotland, Ireland, and England came to the Island of St. John to establish new lives for themselves, most of them either taking over the fishing grounds left vacant by the Acadians or working the Island’s rich red soil on pre-zoned farms, all of which were owned by absentee landlords in Britain. Several new pre-planned settlements sprang up overnight, foremost among them being Charlottetown, the future provincial capital, named in honour of Queen Charlotte, consort of the reigning King George III. Similar waves of immigration hit the Island throughout the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, transforming it from the wild, untamed domain of Mi’kmaq natives and Acadian settlers to an agrarian province with a distinctly Celtic and Anglo-Saxon flavour. Signifying this metamorphosis was the Island’s fourth and final name change; in 1799, the Island of St. John was restyled ‘Prince Edward Island’ after King George III and Queen Charlotte’s third son, Prince Edward, the future father of Queen Victoria. It was in this age of resettlement, when pioneers from the British Isles began to reconstruct PEI into the province it is today, that many of the Island’s most intriguing folktales were born.

One story set during this early period of British colonization is said to have taken place in 1803, when Scottish immigrants first began to settle an area called Brudenell, on the eastern end of the Island. According to one of the many version of this tale, which appears in Sterling Ramsay’s book, a mother and her young daughter vanished from the burgeoning Scottish settlement at Brudenell, and despite the prolonged search that ensued, no trace of them could be found. Several months after the disappearances, a settler was hunting near Brudenell Island, a tiny forested isle in the Brudenell River not far from the settlement, when he saw the distant figures of a woman and a small child apparently standing in the water between the island and the shore. To the hunter’s astonishment, the figures ran atop the water towards the little island, from the shores of which they beckoned for him to follow before disappearing into the trees.

Believing that he had located the missing woman and her child, who had somehow managed to survive in the wilderness in the months succeeding their disappearance, the hunter headed to the stretch of water over which the figures had ran and found a low causeway there connecting the smaller island with the larger, completely covered by a thin sheet of seawater. He could see plainly that the sandbar would be free of water at low tide, but at that moment, the tide was high, rendering the causeway almost impassible. Puzzling over how the two figures could have made their way across the submerged sandbar so nimbly, he headed back to the village with the intention of returning to the island with a boat and a rescue party.

The hunter’s tale met with laughter and incredulity, and his proposed rescue operation never got underway. Several days later, however, a number of his fellow settlers had a similar experience when they saw a woman and a little girl run across the water to Brudenell Island, beckon for them to follow, and vanish into the trees. Two members of the party waited for low tide, when the sandbar was sufficient exposed, and made their way on foot over the causeway to the island. After a brief investigation, the settlers discovered the badly decomposed remains of the missing woman and her daughter lying in a clearing in the island’s interior. From the mutilated state of the corpses, it was clear that the unfortunates had been killed and partially eaten by a bear. “The bodies were taken back to the settlement where they were given a proper Presbyterian burial,” Ramsay wrote, “and the spirits of the two deceased were at last able to rest. In the years that followed, however, many people are reputed to have seen two strange figures motioning for them to follow from the deserted shoreline of Brudenell Island.”

Ghost Ship of the Northumberland Strait

Without a doubt, PEI’s most famous ghost story is that of the phantom ship of the Northumberland Strait- a large old-fashioned schooner, usually with three masts and square rigging, which appears from time to time on the strip of ocean separating the Island from the mainland. Invariably, this mysterious vessel either bursts into flames before the witness’s eyes, or is already burning by the time the witness spots it. The ship sails up or down the Strait for some time before either vanishing or sinking into the sea. Although there is no known historical tragedy to which this eerie apparition is universally purported to be connected, thousands of Maritime residents, both Islanders and mainlanders alike, claim to have seen the ghost ship along every stretch of the 130-mile-long passage, from the West Point Lighthouse near the westernmost end of the Island, to Murray Harbour far to the east, at all times of the year.

According to Frank Harold MacArthur, the phantom ship was first seen in 1786, on PEI’s south-central shore, from the point on which the Seacow Head Lighthouse now stands. During a severe storm, a mysterious ship emerged from the spray and headed straight for the rocks at the base of the point’s sandstone cliffs. By some miracle, the vessel suddenly made an about-face and headed back into the storm, disappearing from view.

MacArthur’s tale bears only vague resemblance to most sightings of the Northumberland Strait ghost ship, many typical examples of which appears in Roland H. Sherwood’s 1975 book The Phantom Ship of Northumberland Strait: And Other Mysteries of the Sea. One such sighting was made in 1965 by Mrs. Alton Langille, a housewife from Cape John, the latter being a narrow peninsula in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, opposite Point Prim, PEI. “I was busy with my housework,” said Mrs. Langille, who considered herself a hardened skeptic at the time of her sighting, “and when I looked up, I was so startled I could hardly believe my eyes. There was this ship, on fire and sailing down the Strait. The telephone was right beside me on the wall, so as I watched the ship, I called some of my neighbours up the road that keep close to the shore. Those others looked and saw what I was seeing, and the word spread up the Cape. Many, as they told me afterwards, stood at their back doors and saw for the first time in their lives the phantom ship of which they had heard. As we watched, the ship just seemed to disappear. There was no mistaking it for a real ship. But that wasn’t the end of it. Two nights later, almost under the same circumstances I saw the phantom ship for the second time. Again I phoned others to make sure I wasn’t seeing things. They, too, as before, saw that same ship. Word was flashed to River John, some six miles away, and soon our Cape road was crowded with cars, loaded with people eager to catch their first sight of the ghost ship. And they weren’t disappointed. That time the Phantom was visible to hundreds of people for a half hour, and then, like the other time, it just seemed to fade away, and where the bright light had been, there was only the blackness of the water.”

Sterling Ramsay included a similar report in his book, this one furnished by a man from Glengarry, on PEI’s western shore. “… As he and his wife were preparing for bed,” Ramsay wrote, “she pointed out the window and asked him whose light that was over there. He was puzzled, because there were no houses in the direction she was pointing, just the waters of the Strait, so he went over to look. What he saw was a full-rigged ship in flames sailing northward up the Strait at an impossible speed. The two of them watched it for about an hour before it disappeared from view.”

In her 1988 book, Ghost Stories and Legends of Prince Edward Island, Julie V. Watson included several sightings of the Northumberland Strait ghost ship that she heard personally from Islanders whom she interviewed. One of these was the first-hand account of the late Debbie Gamble, who hailed from the town of Stratford, PEI, just south of Charlottetown. Gamble’s sighting took place in 1970, when she was sixteen years old, while she was attending a church camp at Rice Point, on the southwestern lip of Charlottetown Harbour about ten kilometres southwest of Holland Cove. “… One night several of us got up to go to the washrooms,” Gamble said. “They were in separate buildings. The other girls went outside before I did and I could hear them saying things like, ‘Oh wow!’ and ‘What is it?’ When I went out, I saw they were looking at the burning ship, just off Robinson’s Island. I couldn’t tell if it was a three-masted ship or not, but the sails were up and people were running about on the deck and it was burning. But it didn’t get burned up.”

One of the most dramatic sightings of the phantom ship of the Northumberland Strait appeared in the May 1954 issue of the magazine Fate. The author- one Roy Grant of Warwick East, Bermuda- claimed that his father had an unusual experience in about 1904, while sailing with six other men on the Northumberland Strait. Just after sundown, Grant’s father and his shipmates spotted a full-rigged ship sailing across their bow no more than 200 yards away. The ship drifted until it was about a half mile away when it suddenly burst into flames.

Like many others before them, Grant’s father and his fellow sailors attempted to catch up with the burning ship, only to watch the spectral vessel drift away from them at exactly the same speed. “First the sails and rigging seemed to burn brightly,” Grant wrote, “then the entire hull appeared to be on fire. During this time, the figure of a man could be quite clearly seen walking along the deck.”

As they tailed it, the phantom ship slowly sank into the water, as if it were being consumed by the flames that engulfed it. When the tips of its three masts touched the surface of the water, the flames that crowned them coalesced together into a roaring blaze, from which emerged the original schooner, whole and unconsumed once again.

Grant’s father and his fellow shipmates chased the phantom ship until dawn, whereupon the object of their pursuit melted into the twilight.

The Bell Ringers of the Kirk of St. James

One type of strange story which appears to be unique to Prince Edward Island and neighbouring Nova Scotia revolves around what locals call “forerunners” – omens which herald impending or concurrent disasters. Related to the Banshee of Irish tradition- the shrieking female phantom whose unearthly wails portend the death of a family member; the doppelganger of German lore- an apparition resembling a living person whose appearance presages bad luck for its real-life counterpart; and the wraith of Scottish tradition – a duplicate of a living person which appears to friends and family members at the moment of the former’s death; the forerunner of Maritime legend can be any unusual occurrence which precedes disaster.

As Nova Scotian folklorist Dr. Helen Creighton put it in her 1957 book Bluenose Ghosts, “Forerunners are supernatural warnings of approaching events, and are usually connected with impending death. They come in many forms, and are startling, as though the important thing is to get the hearer’s attention. The most common forerunners are a picture falling off the wall or a calendar dropping to the floor at the moment when a distant loved one has died. Or you may hear your name called as I did when the mother of a friend died, although she had not called me at all.” Creighton went on to reference another forerunner she described in more detail in her book’s Prologue, in which three loud knocks rapped by invisible knuckles on a wall or door signify a death in the family.

Of all the many forerunners of PEI folklore, many of which are documented in the first chapter of Sterling Ramsay’s book, perhaps the most famous is that alleged to have taken place at the Kirk of St. James, a Presbyterian church near downtown Charlottetown, on October 7th, 1853. Early that morning, so the story goes, a sea captain named Cross set out on foot from the district of Brighton, at Charlottetown’s southwestern end, bound for a particular stable to the northeast, where he expected to pick up a horse that his father had sent him from England. At about 5:30 in the morning, when he was halfway over Black Sam’s Bridge (a bygone structure located near the present-day confluence of Euston and Rochford Street, near downtown Charlottetown), a bell began to ring nearby. Captain Cross’ first instinct was that the peals were those of a ship’s bell signifying the arrival of a ship in the harbour, but when he looked towards the waterfront, there were no strange vessels in sight.

Intrigued, Cross walked in the direction of the incessant clanging and found that it emanated from the bell tower of the Kirk of St. James. As he approached the place of worship, he saw three women dressed in white gowns standing on the church threshold, the double doors of the main entrance wide open before them. The women seemed oblivious to the approaching sea captain and did not raise their eyes in his direction. A fourth white-clad figure could be seen through the slatted windows of the bell tower ringing the church bell vigorously.

Captain Cross was not the only Charlottetown resident drawn to the church by the mysterious tolling. Both the parish’s pastor, Reverend Dr. William Snodgrass, and its sexton, Davy Nicholson, knew that there was no occasion for the bell to be ringing at such an early hour. Suspecting that some impious pranksters had broken into the church and decided to give the town an early morning wakeup call, they both simultaneously leapt out of their beds when they heard the bell’s strident peals and made their ways with all haste towards the Kirk of St. James.

The younger Nicholson arrived at the church around the same time as Captain Cross. Like the latter, he clearly saw three white-robed women standing on the threshold of the church and a fourth in the belfry, laying on the bell. Before the two men had a chance to approach the women and inquire as to the reason for their untimely and unsanctioned bell ringing operation, the church doors closed on them in unison. The mysterious bell ringer also disappeared, leaving no sign of her presence but the lingering vibrations of the bell’s final peal.

Astonished, both Cross and Nicholson tried the church doors, but found them locked. At that moment, Reverend Dr. Snodgrass rounded the corner. Cross and Nicholson told the minister about the three women and the vanishing figure in the bell tower, but Snodgrass dismissed their story as preposterous, demanding that Nicholson open the church and search the belfry for the pranksters that were surely hidden there. The sexton did as requested with the assistance of Captain Cross, but found the tower empty.

Later that morning, a mail steamer called the Fairy Queen left Charlottetown Harbour bound for Pictou, Nova Scotia, on the other side of the Northumberland Strait. At the time of her departure, the Fairy Queen was said to have been in very poor condition, her rotting hull having been freshly painted in an effort to disguise its frail constitution from the eyes of discerning passengers. That afternoon, not far from her destination, the steamer was beset by a ferocious October gale which belied the reassurances of her painted façade. The Fairy Queen sank in the frigid waters of the Northumberland Strait, resulting in the drowning of four women and three men. Three of the deceased were parishioners at the Kirk of St. James, and in the wake of the disaster, many Charlottetown residents suspected that the three white-clad women seen earlier that morning, along with the mysterious bell ringing that initially struck Captain Cross as the peals of a ship’s bell, were forerunners portending the wreck of the Fairy Queen.

The Haunting of Binstead Manor

In the early 1860s, politicians in the Maritime colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island began to consider the notion of amalgamating their respective constituencies into a single union under the protection of the British Empire. Encouraged by this idea, the westerly Province of Canada, comprising what are now the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, proposed marrying itself to this hypothetical Maritime Union to form a great dominion. In early September 1864, delegates of each of these provinces- the so-called Fathers of Confederation- convened in the Province House in downtown Charlottetown, PEI, in what is known as the Charlottetown Conference. This meeting was the first of three conferences that would ultimately give birth to the Dominion of Canada- the fledgling form of the constitutional monarchy we know today.

In the midst of PEI’s transition from a British colony to a province of Canada, while voices were raised and tables pounded in Charlottetown’s Province House, a quieter drama was unfolding in a rural manor on the outskirts of town. We owe our knowledge of this tale entirely to a respectable Victorian lady named Mrs. Georgina Pennee, who lived in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupre, Quebec, at the time she penned her story. As historian Dr. Edward MacDonald put it in his well-researched article in the Spring/Summer 1988 issue of The Island Magazine, “we know little enough about her or her husband; we know a good deal more about her family.” Specifically, Mrs. Pennee’s father was a prominent English banker, conservative politician, and cricket champion named William Ward, while her brothers included such august personages as English theologian and mathematician William Ward II, and English clergyman and cricket champion Reverend Arthur R. Ward.

In 1884, Mrs. Pennee paid a visit to her brother, William, on his estate on the Isle of Wight. There, she met her brother’s neighbour and close friend, the celebrated English poet, Lord Alfred Tennyson. During casual conversation, Mrs. Pennee told Lord Tennyson about a ghost story in which she herself played a small part. The poet was purportedly so intrigued by the tale that he encouraged Mrs. Pennee to write it down on paper in her own words, which advice she followed. In 1889, William’s son, Wilfrid, forwarded his aunt’s testimony to the English Society for Psychical Research, whose members decided to publish it in the Society’s annual journal later that year.

“It was in the year 1856,” Mrs. Pennee began, “that my husband took me to live at a house called Binstead, about five miles from Charlottetown, P.E. Island.” Mrs. Pennee explained that, prior to her tenancy, a new and relatively secluded wing had been added to the manor for the purpose of housing farmhands. The sleeping quarters of this new wing lay on the second floor, adjacent to the old family bedrooms, from which they were separated by a solid doorless wall.

About ten days after moving into the house, the Pennee family began hearing strange noises, the most frequent of which was a low rumbling. “As spring came on,” Mrs. Pennee wrote, “we began to hear shrieks, which would grow fainter or louder, as if someone was being chased round the house, but always culminating in a regular volley of shrieks, sobs, moans, and half-uttered words, proceeding from beneath a tree that stood at a little distance from the dining room window, and whose branches nearly touched the window of the bedroom I have mentioned.”

One night in February 1857, at around 2:00 in the morning, while sleeping in one of the upstairs bedrooms opposite the farmhands’ quarters, a female visitor whose identity Mrs. Pennee withheld “was awakened by a bright light which pervaded the room. She saw a woman standing by the fireplace. In her left arm was a young baby, and with her right hand she was stirring the ashes, over which she was slightly stooping.”

The visitor nudged her bedfellow awake, the latter being another anonymous woman. At that moment, the figure by the fireplace turned towards the two visitors, “disclosing the features of quite a young woman with a singularly anxious pleading look upon her face.” Frightened, the second of the two bedmates screamed and pulled the covers over the heads of herself and her companion. By the time the visitors mustered the courage to peek out from behind the blankets, the mysterious figure had disappeared.

In the spring of 1858, just before leaving on a scheduled trip back home to England, Mrs. Pennee herself came face to face with Binstead’s elusive unpaying tenant. That evening, Mrs. Pennee’s young daughter was ill, and so the lady of the house had the little girl’s bed wheeled into her own bedroom so as to allow her to more easily minister to her needs. At around midnight, Mrs. Pennee noticed a bright light shining beneath the door, and suspecting that her husband was on the other side with a candle or lantern, walked over and opened it without a second thought.

“I found myself face to face with a woman,” Mrs. Pennee wrote. “She had a baby on her left arm… and all around her shone a bright pleasant light, whence emanating I could not say. Her look at me was one of entreaty- almost agonising entreaty. She did not enter the room but moved across the staircase, vanishing into the opposite wall, exactly where the inner man-servant’s room was situated.”

When Mrs. Pennee returned later that year from her trip to England, she learned that Binstead’s resident ghost had made several appearances in her absence, and had regularly startled the farmhands with her disembodied shrieks. Much of the unusual activity seemed to revolve around a certain employee named Henry Newbury, who kept extremely tight-lipped about his experiences. Other farmhands related that, on one particular night, they had heard voices and sobbing emanating from Newbury’s quarters. When the lady of the house questioned Henry directly, the farmhand reluctantly admitted that he had woken up in the night on several occasions to see a woman standing at the foot of his bed, but refused to disclose any additional details about his experiences.

The Pennee family left Binstead in the autumn of 1859, relocating to nearby Charlottetown. While living in the provincial capital, Mrs. Pennee had the opportunity to learn some of the dark history behind the house she once called home. The manor, she discovered, was built in 1840 by a wealthy Englishman, who sold it several years later to a farmer of poor character. In addition to hiring farmhands, for whom he built the additional wing, Binstead’s second owner employed two daughters of a local labourer as domestic servants. Both sisters became pregnant shortly after starting their new jobs, and each gave birth to a boy about nine months later.

Not long after the births, one of the babies and one of the sisters- the latter being the aunt of the former- mysteriously disappeared. The remaining sister continued to work at Binstead for a year and a half, singlehandedly raising her nephew, until her employer sold the house to an Englishman named Fellowes. Her contract terminated, the maid left her nephew in her mother’s care and moved to the United States, never to return.

Incredibly, Mrs. Pennee discovered that the orphaned newphew who had been abandoned by his aunt and raised by his grandmother was none other than Henry Newbury, who, in accepting employment at Binstead, had unwittingly returned to the place of his birth. If the phantom woman seen at Binstead was the ghost of the missing sister, as Mrs. Pennee’s story seems to imply, then the spectral figure whom Henry Newbury found standing at the foot of his bed in the night would have been the shade of his own mother.

Conclusion

In many ways, the Prince Edward Island of today remains unchanged from the old Island of St. John that gave rise to the ghost ship of the Northumberland Strait; the Ile Saint-Jean of the Acadians, which produced the witch of Port La Joye; and the Abegweit of the Mi’kmaq, birthplace of the Mineotta Stone. In Charlottetown, actors in period costume regularly walk down historic streets flanked by stone buildings that haven’t changed for generations. In the countryside, endless potato fields and red earth roads imbue the land with the same pastoral quality for which it has been famed for centuries. And many Islanders the province over still speak with a Maritime brogue evoking the Celtic heritage that gave rise to some of the Island’s most intriguing legends. If you ever find yourself on Prince Edward Island, consider paying a visit to Kellow’s Hollow, Anne Shirley’s Haunted Wood, or any the Island’s secluded coves and beaches, where, when the twilight paints the sandstone cliffs an eerie shade of red, tales of ghosts, forerunners, fairies, and sea serpents seem perfectly at home.

Sources

- Anne of Green Gables (1908), by Lucy Maud Montgomery

- A History of Prince Edward Island from its Discovery in 1534 Until the Departure of Lieutenant-Governor Ready in A.D. 1831 (1923), by Alexander Bannerman Warburton

- Legends of Prince Edward Island (1966), by Frank Harold MacArthur

- The Witch of Port LaJoye (1983), by Joyce C. Barkhouse

- Folklore: Prince Edward Island (1973), by Sterling Ramsay

- Ghost Stories and Legends of Prince Edward Island (1988), by Julie V. Watson

- “HOLLAND, SAMUEL JOHANNES,” by F.J. Thorpe Volume 5 of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (1983)

- “Fake New of a Phantom: The Ghost of Holland Cove,” in the July 21st, 2019 issue of Sailstrait.Wordpress.com

- “James Duncan- Charlottetown’s Biggest Bankrupt- Sailstrait,” by Larry Muffin in the May 7th, 2020 issue of LarryMuffinaThome.Wordpress.com

- “The Legend of Holland Cove,” by F. Gerald, in Volume VII of the Canadian Magazine (1896)

- The Phantom Ship of Northumberland Strait: And Other Mysteries of the Sea (1975), by Roland H. Sherwood

- “The Phantom Ship,” in the May 1954 issue of Fate

- Bluenose Ghosts (1957), by Dr. Helen Creighton

- PEIHistoryGuy.com, by Isaac L. Stewart

- “The Binstead Hauntings Revisited,” by Dr. Edward MacDonald in the Spring/Summer 1988 issue of The Island Magazine

- “On Recognized Apparitions Occurring More than a Year after Death,” in Volume VI of the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research (1889-1890)

Leave a Reply