Quite often Mysteries of Canada readers will question some of the statements made in our stories. This is most common with respect the story of Louis Riel. Most often the disagreement is explained by the admission of the “critic” that they tend to judge Riel by 2003 norms rather that in the context of what was happening in Riel’s time.That introduction brings us to the story of Regina vs. Kikkik and to a remarkable judge by the name of Jack Sissons.

John Howard (Jack) Sissons was born in Orillia, Ontario in 1892.. After graduating from Queen’s University’s Law School in 1917, he practiced law in Grande Prairie for about 20 years. He served a term as Member of Parliament for the Peace River region and he was defeated in the election of 1945. During his time as MP he championed the cause the Metis of the Lesser Slave Lake area in their treaty rights negotiations with Ottawa. This was no mean feat as, at the time (and until recently), the Metis were not considered First Nation people by either the government nor the other First Nations Peoples.

Following his election defeat, Sissons was named as a District Judge in southern Alberta. At the age of 63 he accepted the appointment of Territorial Judge and moved North of Sixty.

Sissons had a reputation as a good judge of the law and good judge of people. When he was presented with a case to judge he delved into the history and culture of the accused and the accuser so that he might deliver a verdict fitting the crime or acquit an accused if no crime was committed.

This brings us to the case of Regina vs. Kikkik.

Kikkik was an Inuit woman who was charged with the murder of one of her children in 1958. In 1958 the federal government forced the relocation of Kikkik and her family from Ennadai Lake to Henik Lake, closer to Hudson’s Bay. The caribou were scarce and starvation soon set in while they were making their trek. Traveling with Kikkik, her husband Hallow and her five children, was her half-brother Ootek.

Several day’s short of their goal the travelers were stranded by a blizzard. Hallow built an igloo and, with Ootek, went ice fishing. While out fishing the starving and delusional Ootek argued with Hallow and accused him of withholding food. Ootek shot and killed Hallow.

On his return to the igloo without Hallow he got into a fight with Kikkik who, in self-defense, stabbed him to death. Stranded and without food, Kikkik made the decision to push on to the nearest outpost, some 5 days away by foot. Shortly into the arduous trek she determined that she could not travel with all five children so she left the two youngest behind wrapped in caribou skins in a snow house she dug out using a frying pan as her only tool.

She was spotted later the same day by a police aircraft and taken to Padley Outpost. Kikkik was afraid of the police and told them that her other two children had probably died. The following day the police found the two girls, one of whom had died in her sleep.

Kikkik was charged with the murder of Ootek (based on her own testimony), child neglect and the death of one of her children. She was brought before Judge Jack Sissons.

In his initial statement to the jury, Sissons explained that Kikkik was a “woman of a Stone Age society” and that she should be judged not based on the black and white letter of the law but rather in light of her circumstances and her culture.

The jury of four whites and two Inuit acquitted Kikkik of all charges.

Sissons, who was known in the north as Ekok-toegee – “He Who Listens” – died in 1969.

Kikkik lived for some years after the trial but she never spoke of the events to her children. Her three surviving children didn’t learn of it until they read the tale in Farley Mowat’s 1959 book, The Desperate People.

Lori

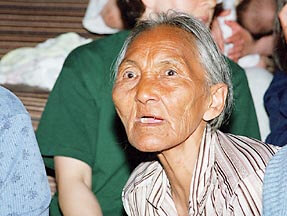

The picture of Kikkik is not the right one, you have Utkatnaaq, one of the members that were relocated.