The Liverpool Packet: Canada’s Most Successful Privateer

If you’re into classic literature, you may have heard of Rudyard Kipling’s 1897 boys’ adventure novel Captains Courageous. This story is about the spoiled son of a New York millionaire who falls overboard a steamer in the North Atlantic, only to be rescued by the crew of a fishing boat off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland (a rich fishing ground southeast of ‘the Rock’). The young protagonist quickly learns that lipping off his new shipmates, as he was wont to do his father’s employees, will earn him nothing but misery. Accepting his situation, he begins to earn his keep on the fishing vessel, forging himself a more virtuous character in the process.

About halfway through the novel, the fishermen bust out a fiddle and begin to sing various maritime tunes, from old sea shanties to an ancient Celtic dirge. One of the first tunes they intone is the Dreadnought, which details the trans-Atlantic route of a speedy American clipper that regularly carried mail from New York City to Liverpool, England, in mid 1800s. The song’s chorus goes: “She’s the Liverpool packet- O Lord, let her go!”- ‘Liverpool packets’ being courier ships that routinely sailed to and from the Port of Liverpool.

The Original Liverpool Packet

Although Kipling’s novel makes no mention of it, there was once a famous schooner actually named the Liverpool Packet which sailed the North Atlantic in the early 1800s. This vessel was a British privateer licensed to capture American ships, and has the distinction of being the most successful privateer to ever sail out of a Canadian port.

Initially christened the Severn, the Liverpool Packet began its life as an American slaver, hauling hapless human chattel from the West Coast of Africa to the fledgling United States. In 1808, both the United States and the United Kingdom outlawed the importation of new slaves into the Americas. Instead of seeking out new legitimate cargo, the captain of the Severn decided to continue the illicit trade with which he had previously been engaged.

In the summer of 1811, a British Royal Navy sloop-of-war captured the slave ship and sold it for 420 pounds sterling to Nova Scotian businessman Enos Collins and two other partners. Collins renamed the schooner the Liverpool Packet and used it to carry mail and passengers between Halifax and the southwesterly town of Liverpool, Nova Scotia.

The War of 1812

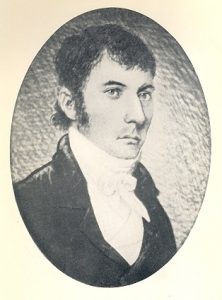

A year following the capture, the United States of America, in response to a British naval blockade intended to prevent U.S. trade with Napoleonic France, declared war on British Canada. The enterprising Collins used the opportunity to convert the Liverpool Packet into a 5-cannon privateer. Command of the schooner was awarded to Liverpool native Joseph Barss Jr., a veteran of the Caribbean theatre of the French Revolutionary Wars who was determined to make up for his lackluster stint in the West Indies. On the advice of his brother, John- an experienced importer familiar with American shipping practices- Barss sailed the Liverpool Packet behind enemy lines to the northern shore of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and lay in wait for American merchant ships bound for Boston Harbor. The schooner’s exceptional speed and Barss’ skill as a captain allowed the Liverpool Packet’s 45-man crew to capture 33 American ships in a single year- a tremendous achievement which earned the vessel a legendary reputation in the North Atlantic, as well as a suitably sinister nickname: the Black Joke. The Packet’s uncanny success even prompted one American shipping intelligence officer, in a dispatch describing the Packet’s relocation to the more northerly coast of Maine, to label Barss an “evil genius”. Soon, a number of American privateers were hunting expressly for the Canadian vessel, determined to pluck that painful thorn from the side of the U.S. shipping industry.

Finally, on June 11, 1813, the Liverpool Packet found herself forced into a battle with a 12-gun American privateer called the Thomas, light winds having precluded her escape. The five-gun schooner was no match for the larger vessel, and Barss wisely surrendered before serious loss of life could occur (despite his efforts, three American sailors were subsequently killed in a panicked boarding skirmish resultant of the two ships smashing together). The Nova Scotian captain and his crew were taken as prisoners of war. Although the crew of the Liverpool Packet was promptly exchanged for American POWs held by the British, Barss himself endured a more lengthy captivity in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, as punishment for the severe damage he had inflicted on American commerce.

The schooner’s new owners renamed their prize the “Young Teazer’s Ghost”- a nod to the American privateer that exploded in Nova Scotia’s Mahone Bay during a skirmish with two Royal Navy warships just two weeks after the Packet’s capture. Despite her lofty appellative, the schooner mysteriously failed to perform in American hands, prompting her crew to rename her the Portsmouth Packet. After a brief and unsuccessful career, the schooner was recaptured by two British Royal Navy warships near Mount Desert Island (Maine’s largest island) and brought back to Halifax, where she was returned to Enos Collins and named the Liverpool Packet once again.

Incredibly, the vessel seemed to regain her good fortune with a Union Jack on her mainmast and a Canadian captain on her quarterdeck. Under the command of Captain Caleb Seeley, another Liverpool resident, the Liverpool Packet captured at least seventeen American ships off the coast of New England. By the end of the conflict, the schooner had captured a whopping 50 ships for the British, their collective cargoes worth nearly a million American dollars- the largest haul of the War of 1812.

When the war was over, Enos Collins (who would invest the small fortune he acquired during the war, eventually becoming the richest man in Canada) and the other co-owners of the Liverpool Packet sold their celebrated schooner to a buyer in Jamaica. Her fate following the purchase remains a mystery to this day.

Want to Help?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Leave a Reply