The Curse of Oak Island- Season 7, Episode 8: Triptych

The following is a plot summary and analysis of Season 7, Episode 8 of the History Channel’s TV series The Curse of Oak Island.

[SPOILER ALERT!!!]

Plot Summary

The episode begins at Smith’s Cove, where the mysterious tarpapered wooden wall and possible remains of the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel were discovered at the end of the previous episode. Various members of Oak Island Tours Inc. puzzle over the structure, which Rick Lagina eventually suggests might be the work of Robert and Bobby Restall, as it bears some resemblance to other structures the Restalls are known to have built. “The only problem I have for this to be Restall work,” Rick says, “is [that the structure would have been] underwater [during the days of the Restall treasure hunt]. Now how would they have gotten here?”

Geologist Terry Matheson examines the wooden wall and opines that the cobble-like rocks that lie beside it, which some treasure hunters had suggested might be the remains of the flood tunnel, were stacked by man. Steve Guptill then tells Matheson that the northern end of this structure lies right next to the southern end of the slipway discovered back in Season 6, Episode 11. Matheson proceeds to examine the rocks with a hand shovel and finds a piece of wood embedded in it, which he identifies as a timber. This find seems to verify that the rock structure is indeed manmade.

That night, the Fellowship of the Dig meets in the War Room, where they speculate as to the nature of the mysterious structure recently discovered at Smith’s Cove. Marty Lagina, who attends the meeting via Skype, encourages his fellow treasures to dig up the structure and “get to the bottom” of it.

The next day, several members of the Oak Island team continue to excavate the structure at Smith’s Cove. Billy Gerhardt removes a quantity of earth beside the supposed cobble, and Gary Drayton scans the fresh trench with his metal detector. Drayton quickly comes across a tapered wrought iron spike which bears great resemblance to one of the objects he discovered at Isaac’s Point in the Season 7 premiere, which blacksmithing expert Carmen Legge identified as a hand point chisel. The object also bears some resemblance to the crib spike discovered on Lot 26 back in Season 6, Episode 3, as well as the crib spikes discovered near the Smith’s Cove slipway back in Season 6, Episode 16. The narrator then suggests that the artifact’s discovery might constitute evidence that the recently-discovered wooden wall was constructed sometime in the 17th or 18th Centuries (the presumed age of the various crib spikes), apparently forgetting that the wall was found covered with 19th or 20th Century tar paper.

That night, the crew meets in the War Room with Oak Island theorist Corjan Mol. Mol presents his theory that classical French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin included secret clues as to the location of the Oak Island treasure in two of his paintings, both of them entitled Et in Arcadia ego (also known as The Shepherds of Arcadia) and inspired by Italian Baroque painter il Guercino’s earlier work of the same name. Poussin’s first rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia, painted in 1627, depicts two shepherds, a reclining man, and a shepherdess in a pastoral setting discovering an overgrown tomb and reading the inscription carved into its side: “ET IN ARCADIA EGO”. Mol suggests that the tomb’s inscription might be an anagram for “GITE NEO ARCADIA”, which, in Italian, means, “Excursion to New Arcadia”.

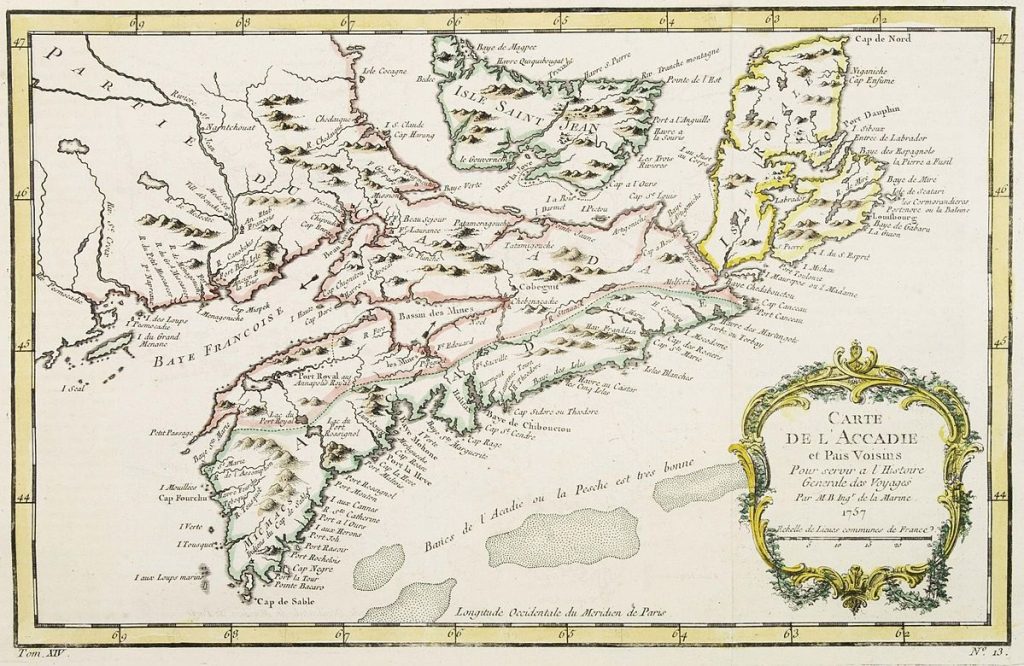

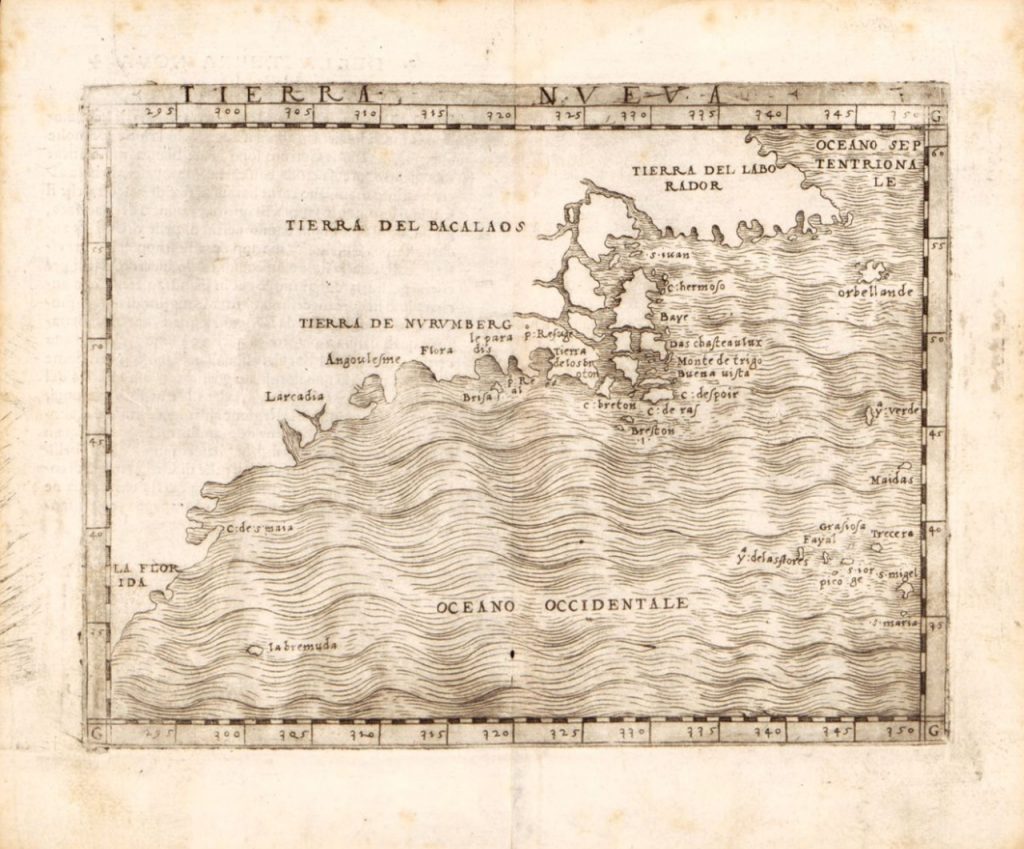

The narrator then explains that Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazano explored North America’s Atlantic coast from North Carolina to Nova Scotia on behalf of King Francis I of France from 1523-24. During the voyage, Verrazano named the beautiful forested coastline north of Virginia “Arcadia” after a legendary pastoral paradise of Ancient Greek mythology. During this exposition, the show displays an old map bearing the title “Carte de l’Accadie”, or “Map of Acadia” in French. Although there appears to be some implication that the map was drawn by Verrazano, the map displayed on the show was actually drawn by French geographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellin in 1757.

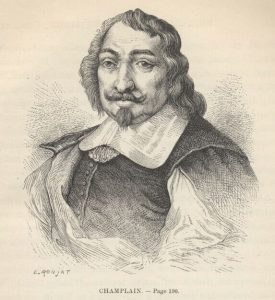

The narrator then explains that the name “Arcadia” gradually moved northeast until, in the early 1600s, it denoted a province of New France which covered an area that now comprises Canada’s Maritime Provinces and much of the state of Maine. 17th Century French explorer Samuel de Champlain decided to omit the ‘r’ from “Arcadia” and call the region “Acadie”, perhaps in an effort to make the word more congruent with native names for extant villages like Shubenacadie (Nova Scotia).

Back in the War Room, Corjan Mol shows the treasure hunters another painting by Nicolas Poussin entitled Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus (1627). This painting, Mol informs the treasure hunters, was made just after The Shepherds of Arcadia, and was intended to form a pendant painting with it (i.e. both paintings were meant to hang beside one another). The painting depicts a scene in the Classical Greek legend of King Midas of Phrygia. According to the legend, a satyr (a woodland deity) granted Midas’ wish for the ability to turn everything he touched into gold. Unable to eat or drink as a result of his new ability, Midas prayed to the Greek god Dionysus (called “Bacchus” by the Romans) to reverse the satyr’s work. A sympathetic Dionysus ordered Midas to bathe in the Pactolus River. In doing so, the Phrygian king cleansed himself of his affliction, depositing gold dust into the riverbed in the process. Mol puts forth the theory that Poussin’s painting, which depicts Midas bathing in the Pactolus River, is a reference to Nova Scotia’s Gold River- a gold-bearing waterway which empties into Mahone Bay just northwest of Oak Island.

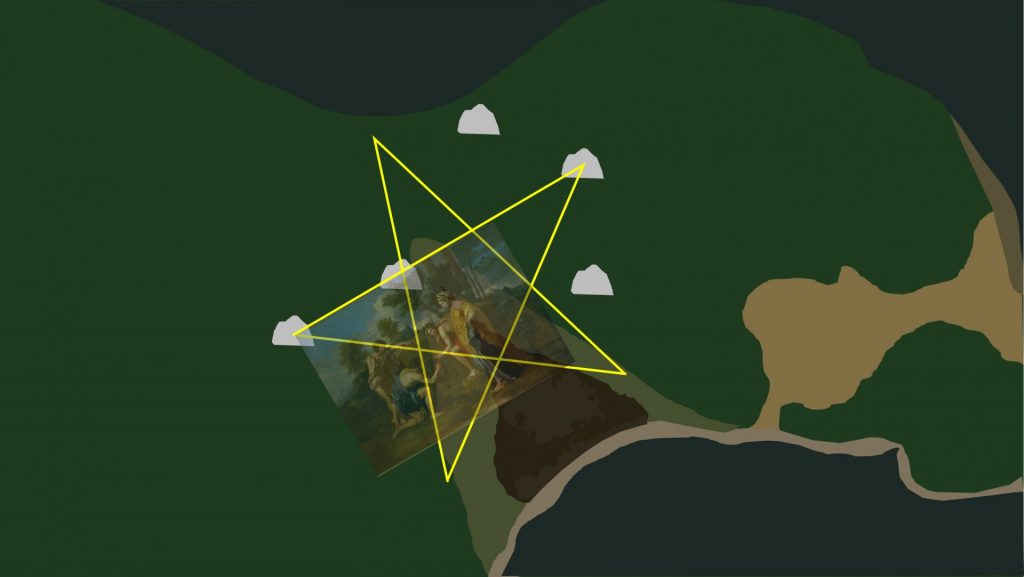

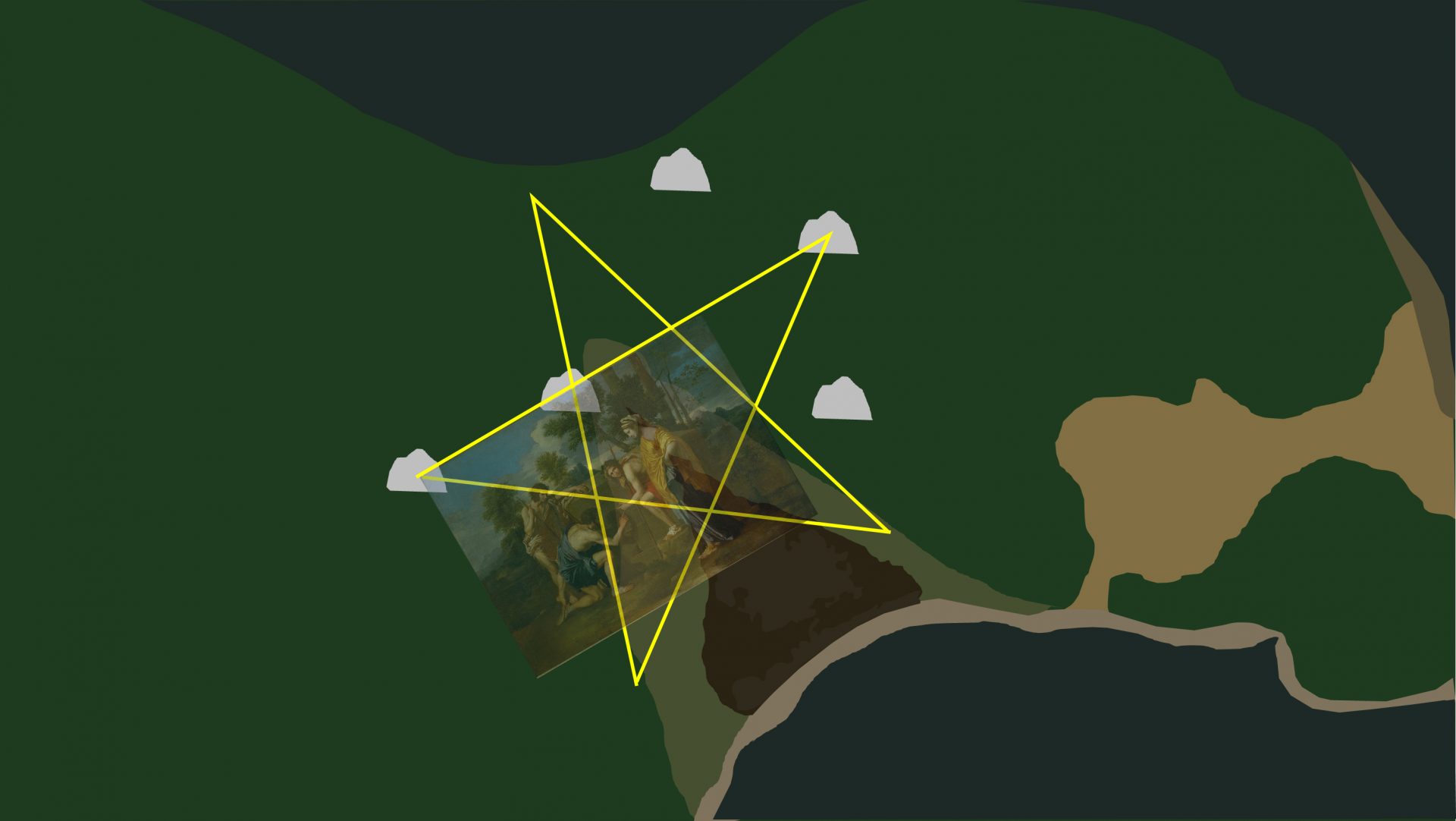

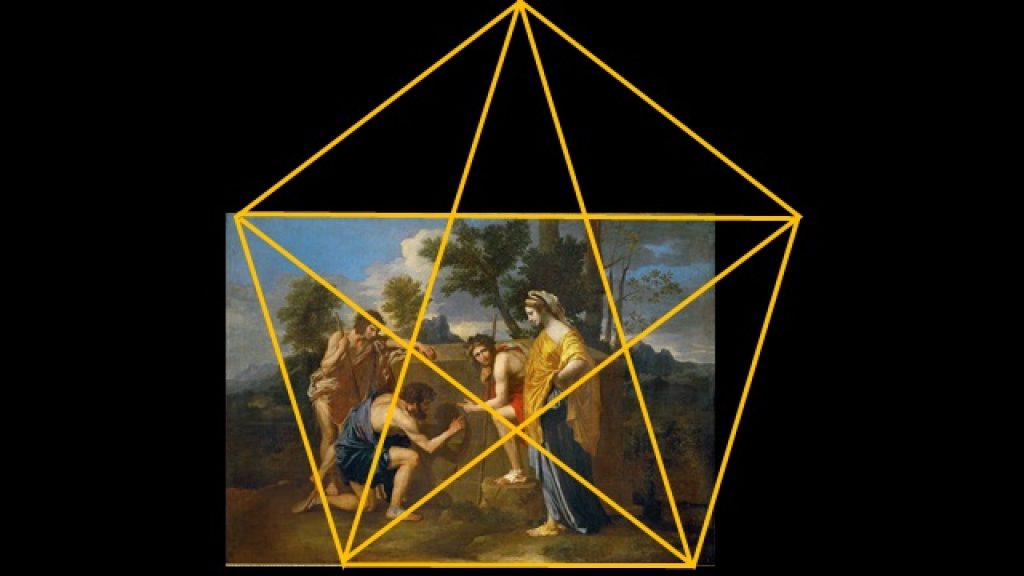

Corjan Mol further argues that Nicolas Poussin’s second rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia, painted in 1637/38, was modeled on a portion of a pentagram. He goes on to suggest that the painting and the pentagram on which it is modeled, when superimposed over top of Nolan’s Cross, forms a treasure map indicating an area of interest near the tip of the Oak Island swamp. Mol finishes his presentation by suggesting that the Knights Templar buried the Ark of the Covenant on Oak Island, and that Nicolas Poussin somehow became privy to their secret.

The next day, Rick Lagina, Steve Guptill, and Tony Sampson meet with GPR experts Don Johnston and Steve Watson at the Oak Island swamp. Using a dingy and a rope laid along gridlines which Guptill prescribed, the crew conducts a floating GPR scan of the swamp. During the process, Johnston and Watson detect a 6-metre-wide anomaly located three metres below the surface.

Later, Jack Begley and Gary Drayton continue to excavate the mysterious wooden structure at Smith’s Cove by hand. Further excavation carried out off-camera has exposed four more log walls which appear to form two square shafts or boxes sitting side by side. The two men are later joined by other members of the team who assist in the excavation. At about three feet below the lip of one of the boxes, Doug Crowell discovers a platform of wooden beams. Despite this interesting development, Rick Lagina suggests that they stop excavating the boxes for the time being and explore more of the surrounding area first. In a later interview, Rick voices his fear that a rigorous investigation of the box-like structure may necessitate their digging a wider hole which might prevent them from accessing other areas of the bump-out with heavy equipment.

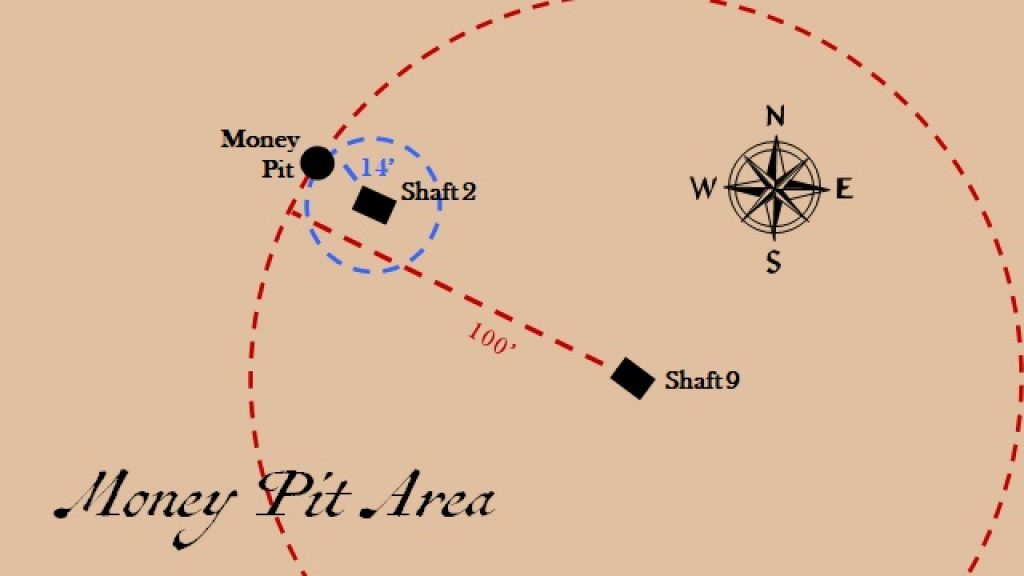

The following day, Jack Begley, Dave Blankenship, Doug Crowell, Terry Matheson, and Scott Barlow meet at the Money Pit area, where Choice Drilling is busy drilling an exploratory drillhole in search of another of the four walls of the 114-foot-deep Shaft 2 (one of Shaft 2’s four walls may have been discovered at the end of the previous episode). The treasure hunters examine a core sample taken from a depth of 19-29 feet below the surface. To their delight, the sample contains a large piece of timber from 24-29 feet which appears to be a piece of a corner of Shaft 2. The narrator informs us that the team will need to intersect one more wall of the shaft in order to definitively determine the orientation of Shaft 2.

The Choice Drilling crew proceeds to sink another hole at one of the suspected locations of a Shaft 2 wall. A core sample taken from an undisclosed depth (later revealed to be 98.5-103.5 feet) in this hole contains a significant quantity of wood. “We’ve got three points now that can’t be just one wall,” says Doug Crowell of the discovery. “So we’ve got two walls.” The crew then agrees to sink another hole in the hope of intersecting the 14-foot-long tunnel which once connected Shaft 2 with the original Money Pit, and to submit the recently-discovered wood samples for dendrochronological dating.

One week later, the crew meets in the War Room to hear the results of the aforementioned dendrochronological test. Craig Tester, who is in attendance via Skype, reveals that dendrochronologist Dr. Colin Laroque (who dated the wood from several Smith’s Cove structures back in Season 6, Episode 21) dated the 98.5-103.5-foot-deep wood from the suspected Shaft 2 wall to 1796. Tester reminds the crew that Shaft 2 is believed to have been constructed in 1805, and remarks that the Laroque’s dating fits perfectly with this. The narrator then remarks that, since it appears the crew has determined the location and orientation of Shaft 2, they finally know the precise location of the original Money Pit.

Analysis

GPR Scan of the Oak Island Swamp

In this episode, GPR experts Steve Watson and Don Johnston conducted a floating GPR scan of the Oak Island swamp using a dingy and ropes laid along gridlines prescribed by Steve Guptill.

This is not the first time a Ground Penetrating Radar scan has been conducted in the Oak Island swamp. Back in Season 2, Episode 8, Pat Campbell and Matt Savelle of Canadian Seabed Research Ltd. scanned the swamp’s southeast corner, the Mercy Point, and the so-called Enochean Chamber area on the swamp’s western edge with a GPR device. Although the scans indicated the presence of several underground anomalies, further investigation yielded little of interest.

Origin of the Name “Acadia”

In this episode, theorist Corjan Mol attempted to draw a connection between the word “Arcadia”, which is inscribed on tomb in Nicolas Poussin’s paintings The Shepherds of Arcadia, and Acadia, an old New French province made up of what is now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, P.E.I., and much of the state of Maine.

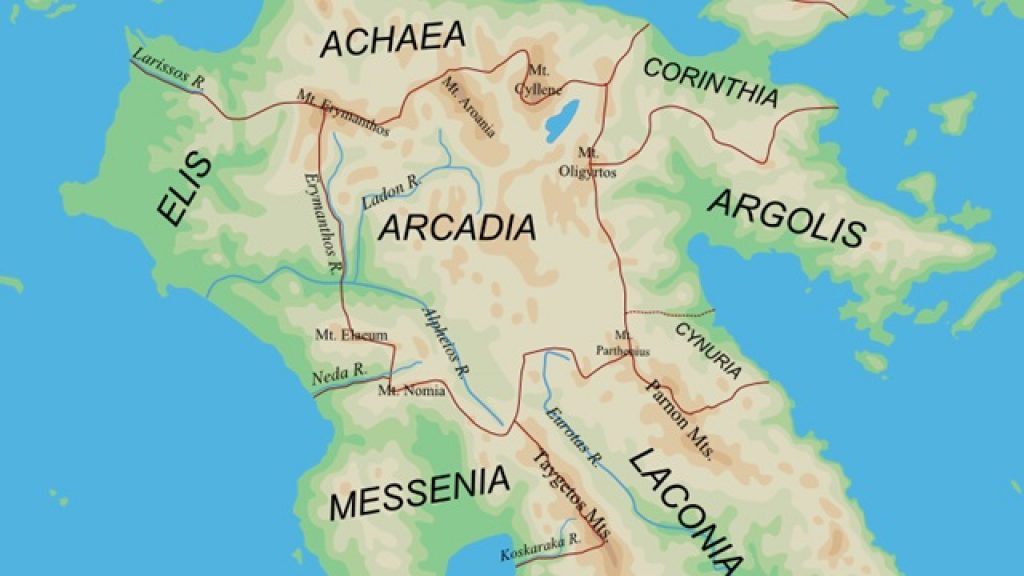

In Classical Greek mythology, Arcadia is a pastoral paradise situated in the sparsely-populated mountainous interior of the Peloponnesian Peninsula. Named after Arcas, a legendary Greek demigod and hunter, the Arcadia of Greek mythology was said to be home to shepherds and nymphs who lived in harmony with nature, ruled over by the god Pan.

As was mentioned in this episode, Italian explorer Giovanni de Verrazano, during his 1523-24 voyage to North America on behalf of Francis I of France, applied the name “Arcadia” to the beautiful wooded Atlantic coast north of Virginia. According to Canadian bibliographer William F.E. Morley in his 1979 article on Verrazano for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, the word Arcadia made its first cartographical appearance on Italian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1548 map of North America’s Atlantic Coast.

King Henry IV of France- who would become a great supporter and sponsor of Samuel de Champlain, the so-called Father of Acadia- referred to the Canadian Maritimes as “La Cadie” in a 1603 colonial license for French explorer Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons. Many historians believe that “La Cadie” has its origins in a native word picked up by French explorers, citing similar native place names like “Shubenacadie” and “Tracadie” as evidence. Samuel de Champlain apparently married Verrazano’s “Arcadia” with King Henry’s “La Cadie” by naming the Canadian Maritimes “L’Accadie”, or “Acadia”, in his writings and maps.

Corjan Mol’s Theory

In this episode, researcher Corjan Mol presented his own Oak Island theory involving classical French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin and his two renditions of The Shepherds of Arcadia. Specifically, Mol believes that the words “Et in Arcadia ego”, which form the inscription on the tombs in Poussin’s paintings, constitute an anagram for “Gite Neo Arcadia”- an Italian phrase which translates to “Excursion to New Arcadia”. Mol contends that these words are intended to draw attention to a particular voyage to the Canadian Maritimes, or “New Arcadia”- perhaps the voyage which led to the interment of the Oak Island treasure.

Mol then showed the Oak Island crew another of Poussin’s paintings entitled Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus. Mol informed the treasure hunters that Poussin created this painting in 1627, the same year in which he painted his first rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia, and claimed that it was meant to hang alongside it. This claim is supported by the posthumous inventory of Cardinal Camillo Massimo, a 17th Century Roman Church official and a major patron of the arts who owned both paintings, which referred to the items as “due quadri compagni”, or “two fellow paintings”.

The painting Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus depicts a scene from Classical Greek mythology and the Roman poet Ovid’s masterwork Metamorphoses. Specifically, the scene depicts the climax of the legend of King Midas of Phrygia, whom a woodland deity had granted the ability to turn everything he touched into gold. Unable to eat or drink as a result of his new ability, Midas prayed to the Greek god Dionysus (called “Bacchus” by the Romans) and asked him to reverse the curse. The sympathetic deity ordered Midas to wash in the Pactolus River. In doing so, the king both cleansed himself of his affliction and deposited alluvial gold into the river. Mol argued that Poussin’s painting of this scene was intended as a reference to Nova Scotia’s Gold River- a gold-bearing waterway which empties into Mahone Bay just northwest of Oak Island.

Mol finished his presentation by putting forth the theory that Poussin’s second rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia, painted in 1636/37, is modeled around the shape of a pentagram. Mol appears to have borrowed this part of his theory from British screenwriter Henry Lincoln, co-author of the infamous 1982 book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which I will explain in greater detail below. Mol further contended that this pentagram on which Poussin’s painting was modeled, when superimposed over Nolan’s Cross, forms a treasure map indicating an area of interest near the apex of the Oak Island swamp. He concluded by suggesting that the Knights Templar buried the Ark of the Covenant on Oak Island, and that Nicolas Poussin somehow became privy to their secret and alluded to it in his work.

The Mystery of Nicolas Poussin

Corjan Mol is not the first researcher to include Nicolas Poussin in his Oak Island theory. In fact, the French painter appears so frequently in various Oak Island theories, as well as in hypotheses regarding other potentially-related mysteries, that a brief biography of the artist and an explanation of his place in some of the more popular of these theses may prove interesting to some readers.

Nicolas Poussin was born in Normandy, France, in 1594. Early on, Poussin displayed a natural aptitude for and interest in drawing. Contrary to his parents’ wishes, he moved to Paris at the age of eighteen, where he pursued a career as an artist. Poussin apprenticed with a variety of established Parisian painters and, in his early twenties, began receiving his own commissions from churches and convents.

In 1622, the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuit Order, hired Poussin to create six watercolor paintings depicting the miracles of Saint Ignatius of Loyala and Saint Francis Xavier, the Order’s founders, both of whom had just been canonized by the Catholic Church. These paintings were seen and admired by Giambattista Marino, a Napolitano poet. At that time, Marino served as court poet to Marie de’ Medici, the mother of the reigning King Louis XIII. In the context of Oak Island, it might be worth noting that, although Marie de’ Medici appeared to have little interest in the exploration of the Americas, her late husband, King Henry IV of France, had used the money she had inherited from her wealthy Florentine family to finance the voyages of explorer Samuel de Champlain, the so-called “Father of Acadia”.

Impressed by Poussin’s paintings, Marino commissioned the young French artist with making fifteen drawings, eleven of them depicting scenes from the Roman poet Ovid’s masterwork Metamorphoses and four of them depicting historic Roman battles. It seems likely that Poussin, who had received little formal education in his youth, first learned the story of King Midas during this period, as this legend features in Book XI of Metamorphoses (recall that the story of Midas is the subject of Poussin’s Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus (1627), which formed a pendant painting with his first rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia).

In 1623, Marino moved to Rome and invited Poussin to join him there. Poussin agreed to do so upon his completion of several major commissions for the residence of Marie de’ Medici and the family chapel of Archbishop of Paris in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame.

In 1624, Nicolas Poussin relocated to Rome, where he would spend most of his professional life. For nearly four decades, the French artist painted hundreds of pieces for Roman cardinals and Italian aristocrats in his own unique classical French Baroque style. In 1627, he painted his first rendition of Et in Arcadia Ego, which appears to be based on another painting of the same name by Italian Baroque artist Giovanni Barbiere, more popularly known as il Guercino.

Il Guercino’s Et in Arcadia ego, painted between 1618 and 1622, depicts two shepherds in a rural setting staring at a skull resting on a cippus, a Roman milestone sometimes used as a funeral memorial. The bricks of the cippus are inscribed with the words “Et in Arcadia Ego”, or “Even in Arcadia I”. As mentioned earlier, Arcadia is the name for the mountainous interior of the Peloponnesian Peninsula, which Classical Greek mythology contends was a paradise populated by shepherds and nymphs. The ambiguous Latin phrase inscribed on il Guercino’s cippus appears to serve as a momento mori– a sobering reminder of our own mortality- asserting that Death is everywhere, even in the paradise of Arcadia.

Nicolas Poussin’s 1627 rendition of Et in Arcadia Ego depicts two shepherds and a provocatively-dressed shepherdess examining an overgrown tomb in the wilderness. Like il Guercino’s cippus, Poussin’s tomb is inscribed with the phrase “Et in Arcadia Ego”. In the foreground of the painting is a reclining man wearing a laurel wreath on his head, whom some art historians have interpreted as Alpheus, a river god of Greek mythology who happens to feature in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It is interesting to note that this figure bears great resemblance to Dionysus in Pouissin’s 1627 painting Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus, which was meant to serve as a companion to Et in Arcadia Ego.

Nearly ten years later, from 1637-38, Poussin painted a second rendition of Et in Arcadia Ego for Cardinal Giulio Rospigliosi, an Italian Church leader who would go on to become Pope Clement IX. This painting differs from Poussin’s earlier version in several ways, including the more dignified dress and bearing of the shepherdess and the letter of the inscription at which one of the shepherds is pointing; in the 1627 painting, a shepherd points to the letter ‘D’, while in the later painting, a shepherd points to the letter ‘R’.

Nicolas Poussin’s forty year residency in Rome was punctuated by an illustrious two-year stint in Paris; in late 1640, the French painter returned to his home country to serve as First Painter to King Louis XIII. For two years, Pouissin created paintings for French churches, religious organizations, and the famous “Red Eminence”, Cardinal Richelieu.

Poussin returned to Rome in December 1642, where he spent the rest of his life painting for a number of patrons he had acquired back in France. He passed away in Rome on November 19, 1665, and was buried in Rome’s Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina.

For centuries, an aura of mystery and intrigue has surrounded Nicolas Poussin and his work. This sentiment is epitomized in a cryptic inscription on the artist’s tomb, which lies below a sculpted relief depicting Poussin’s second version of Et in Arcadia Ego, crafted in 1832. When translated from Latin to English, the inscription reads:

“Spare your pious tears. Poussin lives in this urn. He had given his life without knowing how to die. In this place Poussin is silent, but if you would like to hear him speak, it is surprising- he lives and speaks through his paintings.”

The notion that the great French artist may have been privy to some important secret first appeared in April 17th, 1656, in a letter written by Abbe Louis Fouquet (the future bishop of a region in southern France called Agde) to his elder brother, Nicolas Fouquet, the Superintendent of Finances at the court of the French King Louis XIV. Louis was one of Poussin’s patrons and lived in Rome at the time. To his elder brother in Paris, he wrote, in French:

“I have delivered to M. Poussin the letter which you have done him the honour of writing to him; he has read it with all imaginable joy. You would not believe, Monsieur, either the pains he takes for your service, the affection with which he takes them, or the merit and probity he brings in all things.

“He and I have planned certain things, of which I shall be able to talk to you in depth, which will give you by M. Poussin advantages (if you do not wish to despise them) that Kings would have great difficulty in drawing from him, and that after him perhaps no one in the world will ever recover in the centuries to come; and, what is more, this could be done without much expense and could even turn to profit, and these are things so hard to discover that no one, no matter who, upon this earth today could have better fortune or perhaps equal…”

This cryptic letter is doubly intriguing in light of certain events which succeeded it. In the early autumn of 1661, Nicolas Fouquet was arrested by the Captain of the King’s Musketeers and charged with embezzlement. After an unfair trial which lasted nearly three years, Fouquet was convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for life. The former finance minister spent the rest of his days locked away in the Fortress of Pignerol (located in what is now the town of Pinerolo, Italy). As he was a man of high birth, Fouquet was assigned a valet, or manservant, during his incarceration. Interestingly, whenever Fouquet’s regular valet was indisposed, he was substituted by the so-called “Man in the Iron Mask”, a mysterious unidentified prisoner who was otherwise held in solitary confinement and forced at all times to wear a mask of either iron or velvet.

Five years after Nicolas Fouquet’s death in 1680, King Louis XIV purchased a number of Nicolas Poussin’s paintings, including his second rendition of the Shepherds of Arcadia, and added it to the French Royal Collection. Ten years later, the Shepherds of Arcadia was displayed in the Palace of Versailles, where it remained until its relocation to the Louvre Museum in 1806. Strangely, the painting is said to have disappeared sometime between its introduction to Versailles and relocation to Paris; it curiously failed to appear in a 1750 exhibition of the Royal French Collection in Luxembourg.

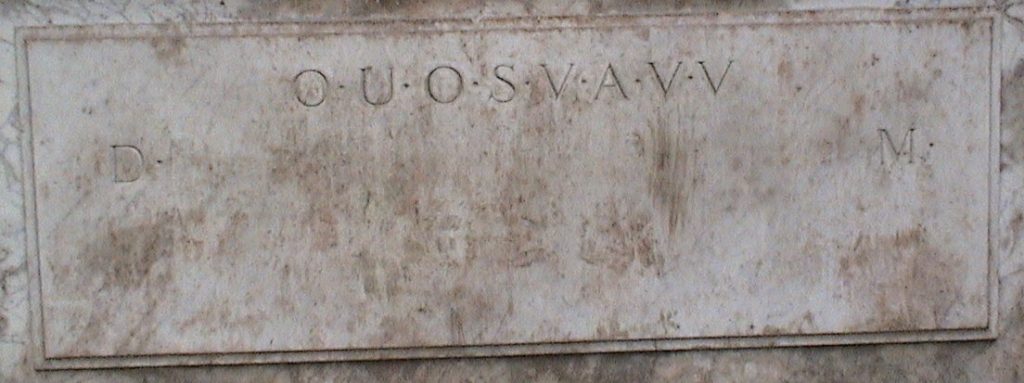

Around that same time, in the mid-18th Century, a wealthy British MP named Thomas Anson- the elder brother of Admiral George Anson of the Royal British Navy who circumnavigated the globe in the 1740s; who features in Gary Clayton’s Oak Island theory, which was presented back in Season 4, Episode 13- decorated the yard of Shugborough Hall, his family’s ancestral home in Staffordshire, England, with eight custom-made megalithic monuments. Among the strangest of these is the so-called Shepherd’s Monument- a rustic arch in which is set a mirror-image relief copy of Poussin’s second rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia, crafted by Flemish sculptor Peter Scheemakers. The Monument also contains the carved bald head of a smiling man, a carved head with goat-like horns resembling the god Pan of Greek mythology (the ruler of Arcadia), and eight Roman letters flanked by a ‘D’ to the lower left and an ‘M’ to the lower right. The sequence of letters on the Shepherd’s Monument, also known as the Shugborough Inscription, appears to form some sort of code. Although many cryptographers have put forth a variety of possible solutions to the code, none of these has been universally accepted.

Some researchers believe that the Shugborough Monument is related in some way to the Oak Island mystery. Many of them point to the fact that one of the shepherds in the Monument’s sculpture has his index finger placed on the letter ‘R’ of ‘ET IN ARCADIA EGO’, almost as if to cover it up. Removing the ‘R’ from ‘Arcadia’ makes ‘Acadia’, the name old French province in the Canadian Maritimes in which Oak Island is located. When this tantalizing possibility is considered in the context of the rest of the scene, the sculpture appears to imply that something important is entombed in Acadia, or Nova Scotia.

One proponent of theory that the Shugborough Monument is connected in some way to the Oak Island mystery is Swedish art director Peter Oberg. Oberg believes that the letters on the Shugborough Inscription stand for numbers which, when added up, equal 2,810- the distance in miles from the Shepherd’s Monument to Oak Island’s Money Pit. He arrives at these numbers by calculating the diameter of circles drawn on the monument’s engraving, and by interpreting some letters as Roman numerals.

Another Scandinavian who believes in a connection between the Shugborough Inscription and the Oak Island mystery is Norwegian organist and cryptographer Petter Amundsen, who presented his own Oak Island theory back in Season 1, Episode 4. Amundsen believes that the inscription forms a three-level cipher. On the first level, the letters form some sort of anagram which, when some letters are switched to their Greek forms, appears to suggest the name ‘Thomas Anson’, the man who commissioned the Shepherd’s Monument. The second cipher level- decoded using a key in a poem, Greek mythology, and astronomy- allegedly creates a celestial map which leads to Oak Island. The third alleged cipher level- first discovered by another Norwegian named Oystein Bruno Larson- involves turning the inscription letters into geographic co-ordinates which lead to a location 1.5 nautical miles from Oak Island. Amundsen presented his theory in the book he co-wrote with Norwegian novelist Erlend Loe, entitled Organisten, or The Organist.

When one considers the mystique that Nicolas Poussin and his paintings have garnered over the years as a result of the Shugborough Monument and the cryptic inscription that adorns his tomb, it is easy to understand how the French painter and his famous second rendition of The Shepherds of Arcadia found their way into the heart of a clever, sinister 20th Century hoax upon which an entire genre of misguided Oak Island theories are based. The story of this hoax begins in 1969, when British screenwriter Henry Lincoln picked up a copy of the recently-published book Le Tresor Maudit de Rennes-le-Chateau, or “The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau”, by French author Gerard de Sede. The book puts a twist on a little local legend endemic to a sleepy town on southern France called Rennes-le-Chateau.

The original legend on which de Sede based his book was first proliferated in the mid-1950s by a local restaurateur named Noel Corbu, and dealt with a former local character named Father Berenger Sauniere. Sauniere was a Roman Catholic priest who was appointed to Rennes-le-Chateau’s Church of Saint Mary Magdalene in 1885. In the late 1800s, Sauniere renovated his dilapidated parish and built a castle-like library and villa for himself, paying for the costly projects with mysteriously-acquired money. The Catholic Church conducted an investigation into Sauniere’s mysterious wealth and eventually charged him with simony- the fraudulent sale of religious favours. Specifically, the Church accused the priest of pressuring people into making donations he did not need and accepting payments for hundreds of Masses he never intended to say (in the Catholic Church, it is common for parishioners to ask a priest to offer a Mass for a specific intention, like the repose of a recently deceased relative). According to Noel Corbu, however, the source of Sauniere’s wealth was not simony, but rather the lost treasure of the 13th Century French Queen Blanche de Castile, who raised ransom money for her son, Prince (and later Saint) Louis IX, after his capture by Egyptian Saracens in the Seventh Crusade at the Battle of Al Mansurah. Sauniere located this treasure by following clues laid out in parchments he discovered in a particular pillar in his church during the renovations he financed in the late 1800s.

The French author Gerard de Sede put a different spin on the legend of Berenger Sauniere. In his book, he wrote that the priest, during his renovation of the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene, discovered four parchments in a pillar which supported the altar. De Sede included what purported to be photocopies of these parchments in his book. Two of the parchments contained genealogies which stretched back to the days of the Frankish Merovingian dynasty. The other two contained passages from the Gospels written in Latin. According to de Sede, Sauniere suspected that the parchments contained coded messages within their texts, and took them to Paris to have them deciphered. During his Parisian excursion, the French priest visited the Louve Museum, where he purchased prints of three paintings, one of them Nicolas Poussin’s The Shepherds of Arcadia. Upon his return to Rennes-le-Chateau, Sauniere began spending an extraordinary amount of money on various building projects, having become inexplicably and spontaneously wealthy. De Sede implies in his book that Sauniere, aided by the codes in the parchments, must have discovered some sort of treasure in Rennes-le-Chateau.

During this time, locals observed that Sauniere spent many a night in the church cemetery engaged in some strange and mysterious business, moving tombstones and effacing epitaphs. One of the graves which the priest defaced was that of Marie de Blanchefort, a local aristocrat who died in 1781. Fortunately, the markings on de Blanchefort’s grave had already been recorded in a booklet entitled Les Pierres Gravees du Languedoc, or “The Engraved Stones in Languedoc”, written by a man named Eugene Stublein in 1884. De Sede included photocopies of Stublein’s interpretations of these markings- which included those inscribed on de Blanchefort’s headstone as well as words carved into a rectangular stone set perpendicular to it- in his book.

In 1969, while vacationing in the Pyrenees, an English screenwriter named Henry Lincoln purchased a copy of de Sede’s book. While examining a photocopy of one of the parchments Sauniere is said to have discovered hidden in a pillar in his church, he noticed that some of the Latin letters dipped below the others. To his astonishment, Lincoln found that these anomalous letters, when put together, formed a message in French. When translated to English, the message reads: “To Dagobert II, King, and to Sion belongs this treasure and he is there dead.”

Fascinated, Lincoln believed that de Sede’s story of Sauniere and the mysterious treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau would make for an excellent BBC documentary. He said as much to a certain BBC producer, who agreed with him and sent him to Paris to interview Gerard de Sede. Ever since he deciphered the code in the parchment, Lincoln had suspected that the French author had discovered the secret message as well, and was curious as to why he failed to include the decipherment in his book. He said as much to de Sede in his interview, to which the author replied, “Because we thought it might interest someone like you to find it for yourself”. De Sede’s use of the word “we” troubled Lincoln, as it implied the presence of some shadowy association behind the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau.

As the BBC prepared their documentary on the tale of Berenger Sauniere, Henry Lincoln received a letter from Gerard de Sede in which the French author disclosed the solution to the code in another of the parchments discovered in the Church of Mary Magdalene. When translated from French to English, the coded message reads:

“SHEPHERDESS NO TEMPTATION THAT

POUSSIN TENIERS HOLD THE KEY

PEACE 681 BY THE CROSS AND THIS

HORSE OF GOD I COMPLETE THIS

DAEMON GUARDIAN AT MIDDAY

BLUE APPLES”

The words “Shepherdess” and “Poussin” reminded Lincoln that, in de Sede’s book, Sauniere is said to have purchased a print of Nicolas’ Poussin’s 1637 painting The Shepherds of Arcadia. With this in mind, Lincoln looked at the various photocopies in de Sede’s book and made an extraordinary discovery. One of the inscriptions on the tomb of Marie de Blanchefort is flanked by columns of letters, some from the Latin alphabet and others from the Greek alphabet. When the letters from the Greek alphabet are exchanged for their Latin counterparts, a Latin phrase emerges: “Et in Arcadia Ego”- another clear connection between Nicolas Poussin and the mystery of Rennes le Chateau.

Around this time, Lincoln received another letter from Gerard de Sede. In the letter, the French author claimed that he and his shadowy associates, to which he alluded earlier, had discovered a tomb near Rennes-le-Chateau which bore remarkable resemblance to that depicted in Poussin’s painting. Using the directions that de Sede provided, Lincoln found this tomb on the side of the road between the villages of Serre and Arques, just a few miles from Rennes-le-Chateau. Indeed the tomb and its setting was nearly identical to that in Poussin’s The Shepherds of Arcadia, down to the foliage in the background and a rock which rests at the base of the sarcophagus. Even more startling were the similarities between the surrounding landscape and the backdrop of Et in Arcadia Ego. Lincoln quickly identified four mountaintops in Poussin’s painting which corresponded almost perfectly in both shape and placement with those surrounding this roadside sarcophagus. It seemed clear that Nicolas Poussin had painted this particular tomb and its surroundings in The Shepherds of Arcadia, either having visited the location or worked off of detailed sketches.

Henry Lincoln spent the next seven years attempting to solve the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau, assisted on occasion by tips he received from the author de Sede and his mysterious associates. Lincoln produced three films for the BBC which documented his progress: The Lost Treasure of Jerusalem, produced in 1971; The Priest, the Painter, and the Devil, produced in 1972; and The Shadow of the Templars, produced in 1979. In his second film, he consulted Professor Christopher Cornford of London’s Royal College of Art. Cornford analyzed The Shepherds of Arcadia and determined that it appeared to be modeled around a portion of a pentagram. The professor attempted to explain the presence of this pentagram by suggesting that its inclusion implied Poussin’s attempt to connect his painting with the occult, or with the Cult of Pythagoras- an ancient Greco-Italian religion which revolved around geometry, mathematics, and Classical Greek mythology. Corjan Mol, who presented his own theory in this episode of The Curse of Oak Island, appears to have borrowed this part of Lincoln’s work.

Following the publication of The Shadow of the Templars in 1971, Henry Lincoln teamed up with New Zealander Michael Baigent and New Jerseyite Richard Leigh- researchers who shared his interest in the Knights Templar. Together, the three men began to research the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau. Shortly after the formation of this alliance, Lincoln was contacted again by Gerard de Sede, who directed him to a particular document in the Bibliotheque Nationale, the national library of France. This document, called the Dossiers Secret d’Henri Lobineau, or the “Secret Files of Henri Lobineau”, contained, among other things, diagrams depicting the genealogy of the Merovingian dynasty and references to an ancient secret society called the Priory of Sion. The Priory of Sion, the document contented, was formed in the year 1099 by descendants of the Merovingian dynasty. Following the First Crusade, it formed the Knights Templar as its military arm and financial branch. Over the years, it has been led by men of status and acclaim, including Leonardo da Vinci, Sir Isaac Newton, and Victor Hugo. Its motto is “Et in Arcadia ego”, and its stated mission is the reinstallation of a Merovingian king on the throne of France. De Sede later confessed to Henry Lincoln that he was a member of the Priory of Sion, and that the organization’s current Grandmaster was a Frenchman named Pierre Plantard, who was the heir to the Merovingian dynasty.

Using the Dossiers Secret as one of their major sources, Lincoln, Baigent, and Leigh wrote a book entitled The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which was published in 1982. The book revolves around an offensive thesis which I will not dignify here with an exposition. One of the many propositions put forth in the book is that the phrase “Et in Arcadia Ego” could be considered an anagram for “I! Tego Arcana Dei”- Latin for “Begone! I Conceal the Secrets of God”. This proposal appears to have inspired Corjan Mol’s own interpretation of “Et in Arcadia Ego” as an anagram for “Gite Neo Arcadia”, or “Excursion to New Arcadia”.

Due to its controversial nature, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was commercially successful, prompting its three authors to pen a sequel to it entitled the Messianic Legacy. In 2003, American writer Dan Brown wrote an enormously successful mystery thriller novel entitled The Da Vinci Code, which appears to be based on the thesis outlined in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. Three years later, Brown’s novel was adapted into a controversial Hollywood movie featuring actor Tom Hanks, bringing the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau, in a roundabout way, to an international audience.

For decades, a number of researchers- foremost among them French journalist Jean-Luc Chaumeil- have chipped away at the story of Rennes-le-Chateau and the Priory of Sion. Beneath a façade of mystery and intrigue, they have uncovered evidence of an extraordinarily complex hoax concocted by three men: the writer Gerard de Sede; the Priory of Sion’s supposed Grandmaster, Pierre Plantard; and a French surrealist named Phillipe de Cherisey. Plantard, the mastermind of the plot, conceived the story of the Priory of Sion, a medieval secret society with roots in the Merovingian dynasty responsible for the formation of the Knights Templar, whose Grandmasters included the movers and shakers of European culture. A fifty-year-old tomb near Rennes-le-Chateau which bore remarkable resemblance to that depicted in Et in Arcadia Ego prompted him to give Nicolas Poussin and his famous painting places of prominence in the story. Phillipe de Cherisey then created ‘evidence’ for the organization’s existence by fabricating a number of historical documents, including the parchments which Sauniere purportedly discovered in his church; the 1884 booklet of Languedoc engravings by Eugene Stublein; and the all-important Dossier Secret, which Plantard submitted to the Bibliotheque Nationale in 1967. Gerard de Sede completed the hoax by writing his book The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau, a colourful spin on a local legend, including photocopies of several of de Cherisey’s forged documents therein, and waiting for someone like Henry Lincoln to stumble upon it and take the bait.

Although the alleged connection between Nicolas Poussin and the Priory of Sion has been debunked, the unsolved Shugborough Inscription and cryptic inscription on Poussin’s tomb hint at the possibility that the French painter was privy to some sort of secret, clues to which he embedded in his paintings. Is it possible that this secret has something to do with the Oak Island mystery? Let me know your thoughts in the Comments section below.

Thanks for Reading!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our books:

kormath

THis was the worst episode yet. The theory about the painter leaving clues is total bogus. The Gold River wasn’t named until the early 1800’s, hundreds of years after the paintings were painted. It was originally called the Gould River after the first settler Mr. Gould, then changed to Gold River. They’re really reaching now aren’t they?