The Curse of Oak Island- Season 7, Episode 13: Bromancing the Stones

The following is a plot summary and analysis of Season 7, Episode 12 of the History Channel’s TV series The Curse of Oak Island.

[SPOILER ALERT!!!]

Plot Summary

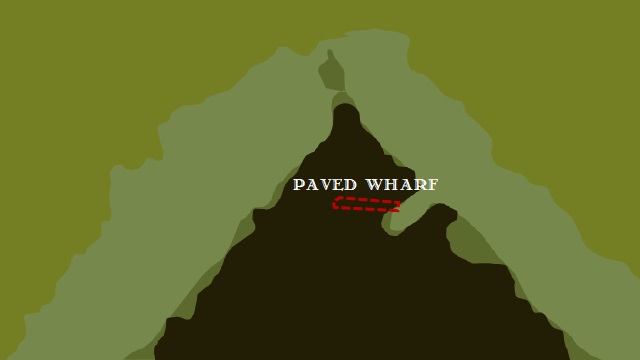

Rick Lagina takes Tom Nolan to Oak Island’s recently-drained swamp and shows him the stones that make up the Paved Wharf. “Oh, there’s no way that’s natural, Rick,” Nolan says. “Look at it. It’s just layered right on top… It’s like you’re standing on a paved road in the middle of a bog.”

Later, the Oak Island crew congregates in the War Room. There, Rick Lagina and Doug Crowell show their fellow treasure hunters photos of the casements and the countermine tunnel at the Fortress of Louisbourg, which they visited the previous episode, and discuss their evocation of the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel. Crowell then shows the crew an old photo given to him by a Louisbourg historian which depicts a stratum of rocks lying on top of a layer of earth. This structure, which Crowell says is an original piece of Louisbourg flooring, bears remarkable resemblance to the Paved Wharf in the swamp.

Later, Rick Lagina and Billy Gerhardt meet Dr. Ian Spooner at the Paved Wharf. Upon examining the formation, the geoscientist finds a stick crushed between two rocks, which he claims to be an indication that the feature could not have been formed by a glacier. When Rick asks Dr. Spooner to estimate the date at which the stones were laid down, the geoscientist suggests that the carbon date the stick he found between the rocks.

The next day, Billy Gerhardt excavates more of the swamp in the area of the Paved Wharf in an effort to define the extent of the structure. As the heavy duty equipment operator goes about his work, Jack Begley and Gary Drayton search for metallic objects in the spoils that he removes. After digging through dirt and detritus for some time, Gerhardt uncovers another layer of rocks nearby, which Gary suggests might constitute an extension of the Paved Wharf. The treasure hunters are then joined by Rick Lagina, Craig Tester, and Steve Guptill, the former of whom task the latter with determining the depth of this new rock layer and comparing it with that of the Paved Wharf. The new rocks prove to lie one foot below sea level- a foot higher than the Paved Wharf.

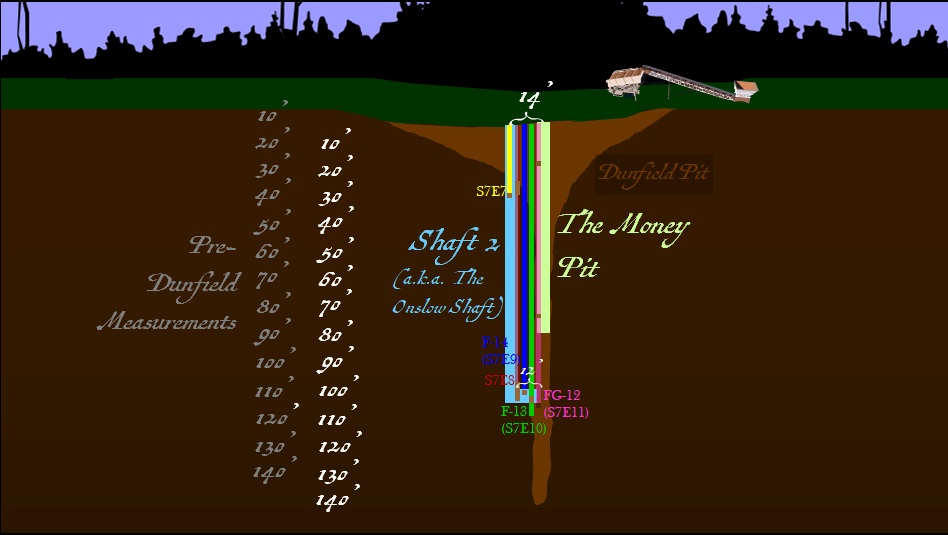

Later that day, Craig Tester, Charles Barkhouse, the Terry Matheson meet at the Money Pit area, where the Choice Drilling crew is busy sinking exploratory boreholes in the area at which the team now believes the original Money Pit once lay. While extracting a core sample from a depth of 109-119 feet, drillers Mike Tedford and Colton Robinson claim that their drill fell into some sort of subterranean void. The core sample appears to contain undisturbed soil and crumbly limestone, which Craig interprets as an indication that the drill failed to intercept the original Money Pit. Craig suggests that they sink another hole about a foot and a half away.

The next day, Rick Lagina, Billy Gerhardt, and Laird Niven drive to the Dartmouth Heritage Museum in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, having acquired a permit to excavate the museum’s yard in search of the supposed 90-foot stone which they learned might be buried there in Season 7, Episode 7. Billy Gerhardt begins digging 20’x20’ hole in the yard with a backhoe. Despite finding a number of bricks and a large boulder, he fails to unearth anything resembling the legendary 90-foot-stone. The boys are then joined by Kevin Rideout, the area local who had previously informed them of the stone’s existence, a tour guide having pointed it out to him decades before. Rideout says that he believes the treasure hunters are looking in the right place, but notes that the surrounding area is more elevated than he remembered it to be in the past, suggesting that the stone may have been covered up in some sort of landscaping project carried out years ago. Accordingly, Billy Gerhardt digs the hole a little deeper, yet fails to unearth anything of interest.

Meanwhile, Gary Drayton and Jack Begley go metal detecting on the shores of the Eye of the Swamp. The treasure hunters quickly unearth the iron head of a pickaxe, which Gary suggests is an old pick used for tunneling. Several feet away, they find what appears to be the rusted head of a round point shovel.

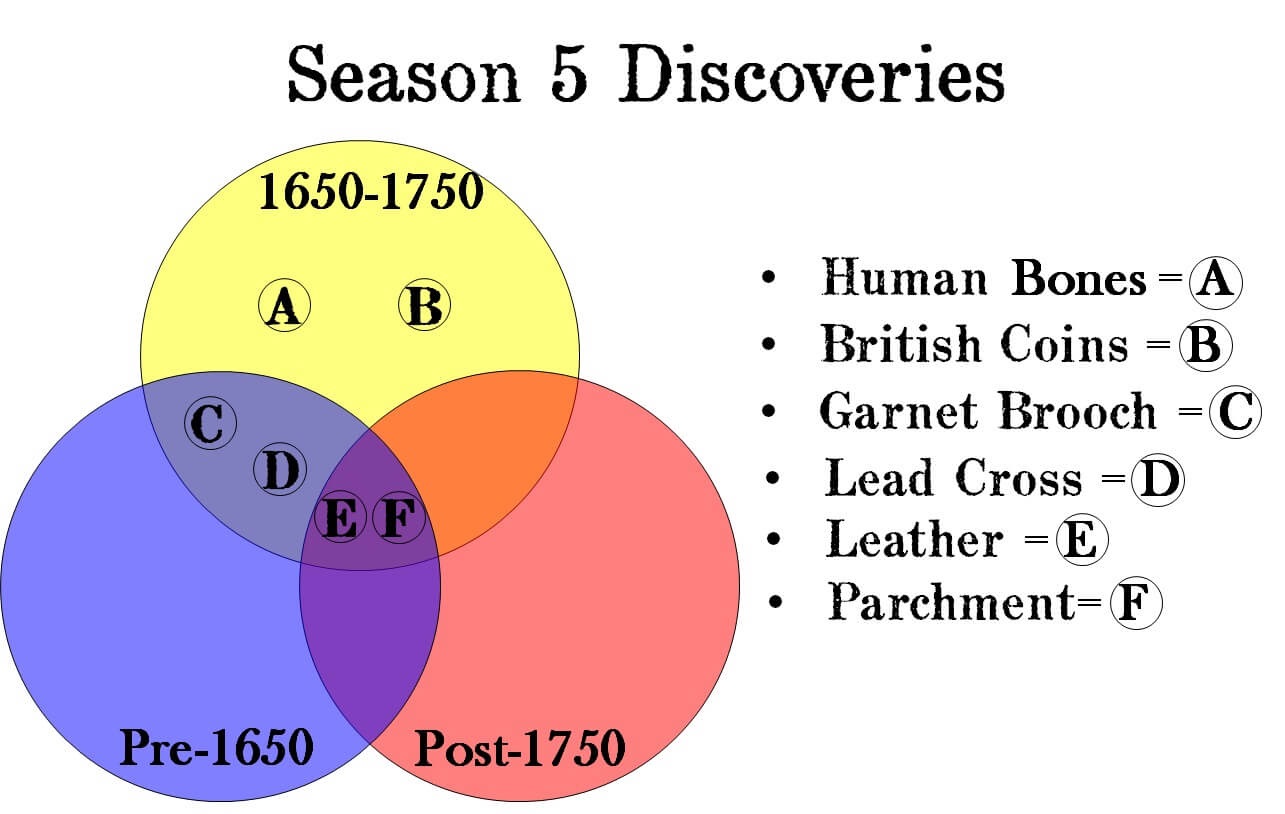

Later that night, the Fellowship of the Dig meets in the War Room to learn the results of the carbon dating of the 106-foot-deep wood found in Borehole FG-12 in Season 7, Episode 11, which some of the crew members suspected might be a fragment of the original Money Pit. Craig Tester reveals that the wood was dated from 1626-1680- a date range which roughly corresponds with many of the artifacts discovered in the Money Pit area throughout Season 5. Marty Lagina remarks that the upper range of the wood’s carbon dating is also consistent with that of the twigs which Dr. Ian Spooner and his graduate students discovered in core samples taken from the Eye of the Swamp in Season 7, Episode 9.

“I wonder what was happening in the area [in the] late 1600s, early 1700s,” muses Gary Drayton.

“Yeah, that’s the question,” Marty replies.

Analysis

Follow-Up on the Stone at the Dartmouth Heritage Museum

In this episode, Rick Lagina, Billy Gerhardt, and Laird Niven followed the lead introduced by Kevin Rideout introduced in Season 7, Episode 7, indicating that Oak Island’s legendary 90-foot-stone might lie in the yard of the Evergreen House in Darmouth, Nova Scotia- now the home of the Dartmouth Heritage Museum. Despite digging a deep 20-foot by 20-foot hole in the spot at which Rideout believed the stone once lay, the treasure hunters were unable to unearth anything of interest.

Carbon Dating of the Wood from the Money Pit

In this video, we learn that the wood brought up from Borehole FG-12 in Season 7, Episode 11, which some of the crew members suspected might be a piece of the original Money Pit, was carbon dated from 1626-1680. This date range corresponds with a number of Oak Island theories, including the French theory, the English theory, the Spanish theory, and the notion that New English treasure hunter and later politician Sir William Phips is the man behind the Oak Island mystery.

The Acadian Theatre of the Nine-Years-War

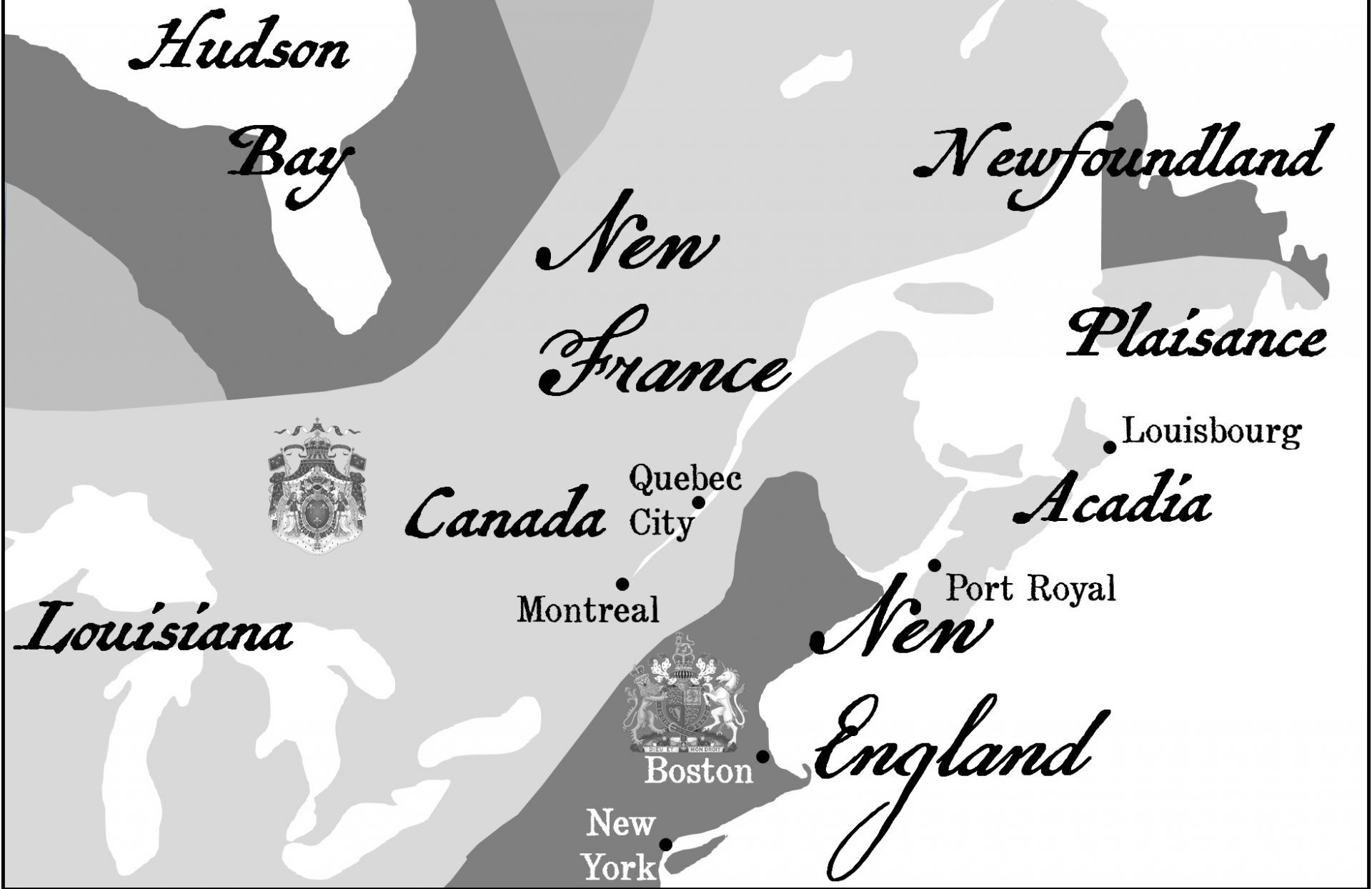

In this episode, the wood from the Money Pit area brought up from Borehole FG-12 in Season 7, Episode 11 was carbon dated from 1626-1680, prompting Gary Drayton and Marty Lagina to wonder aloud what was happening in the area in the late 1600s. The answer is that the Atlantic Northeast was teetering precariously on the precipice of war- namely the Nine Years’ War, known as King William’s War in Canada and the United States, the outbreak and early stages of which I outlined in the following articles: Setting; the 1689 Acadian Theatre; and the 1690 Acadian Theatre.

The first few years of King William’s War were characterized by Wabanaki and French-Canadian raids against New English settlements, many of these led by Jean Vincent de Saint-Castin and a French Sulpician missionary named Father Louis-Pierre Thury. In 1690, the New Englanders began to hit back, launching their own counteroffensives into Acadia. The first of these campaigns was led by Benjamin Church, a veteran of King Philip’s War who trained his own soldiers in the guerilla tactics of the East Coast Native Americans, forming his own united of special light infantrymen who constituted the first regiment of what would one day become the U.S. Army Rangers. Church’s first expedition into Acadia culminated in a battle near what is now Portland, Maine.

The second New English offensive against Acadia was led by Sir William Phips, a character who features in an interesting Oak Island theory presented by engineers Graham Harris and Les MacPhie in their book Oak Island and its Lost Treasure.

William Phips was considered something of a homegrown hero in New England. A lowborn shipwright and lumber merchant from the colony of MAssachussets, he had allowed his hard-won livelihood to literally go up in flames in order to save the lives of the residents of a particular village during a Wabanaki raid that took place during King Philip’s War. More recently, he had been awarded a knighthood from King William III for salvaging the contents of a sunken Spanish treasure galleon in the Caribbean, a portion of which Harris and MacPhie contend lies at the bottom of the Money Pit. Despite Phips’ complete lack of military experience, the Massachusetts militia promoted him to the rank of Major General in the spring of 1690 and gave him command of the naval expedition against New France.

First, Phips launched an attack against Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, situated on the southwestern shores of the Acadian Peninsula. To his delight, Phips found that Port Royal’s ninety soldiers were actually in the process of dismantling their fortifications so that stronger ones could be built in their place. None of the fort’s cannons were presently functional, and to top it off, the village’s armory housed a total of nineteen muskets at that time. The garrison surrendered without a fight.

About a month after his capture of Port Royal, Sir William Phips tasked one of his officers with raiding the Acadian village of Chedabucto, situated at the tip of the Acadian Peninsula just across the Chedabucto Bay from Ile Royale, or Cape Breton Island. In addition to housing a French military post called Fort Saint Louis, Chedabucto served as the headquarters of the Company of Acadia, an important French fishing company.

On June 3rd, 1690, Phips’ captain and eighty-eight New English soldiers stormed Fort Saint Louis. Although they were heavily outnumbered, the twelve Acadian soldiers who manned the fort put up a fierce six-hour defense. When the New Englanders began to firebomb the fort, the French defenders realized that future resistance would be futile. They surrendered to the New English captain, who allowed them to retreat across the Gulf of St Lawrence to the French colony of Plaisance, on the island of Newfoundland.

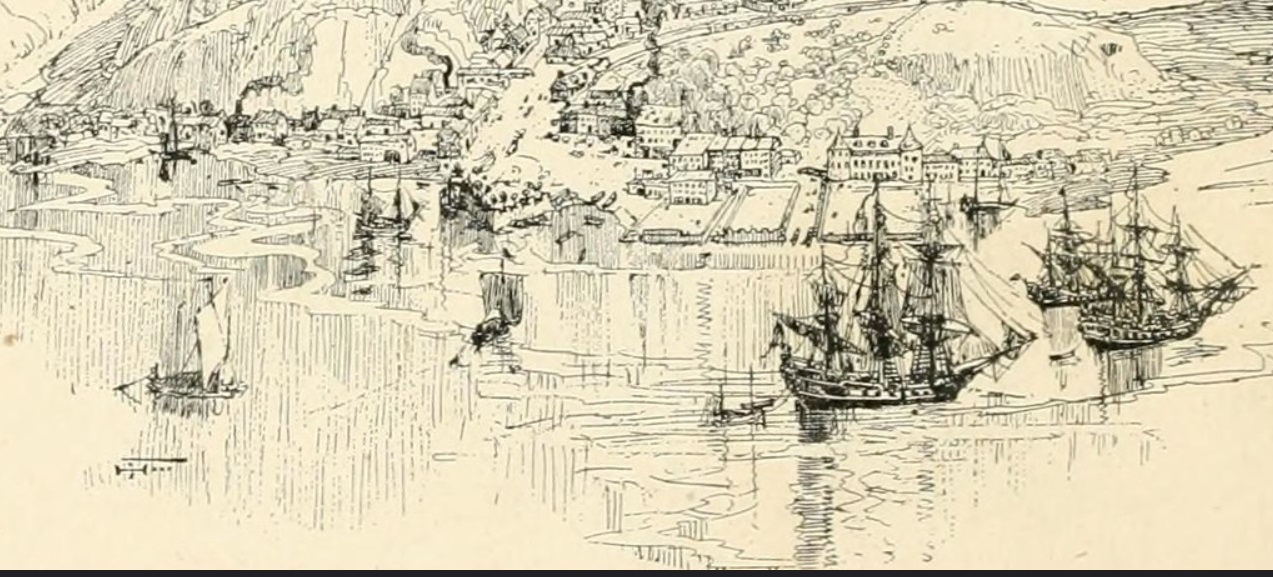

That fall, Phips launched a third offensive against the French, this one targeting the city of Quebec, the heart of New France. Accompanied by 2,300 Massachusetts militiamen, Phips sailed from Boston up the Atlantic Coast and further up the St. Lawrence River. The New English army reached the New French capital on October 16th, 1690, whereupon Phips sent an envoy into the city to deliver his terms of surrender. The French commander, Governor Frontenac, had the emissary blindfolded and brought to his residence, the Chateau St. Louis, where his war council was assembled. There, the envoy delivered Phips terms of surrender, telling Frontenac that he had one hour to reply. The enraged Governor famously retorted that the only reply Phips would receive would be from the mouths of his cannons.

That evening, the New Englanders launched their assault on Quebec. From the very start, it was clear that their enterprise was doomed to fail. Members of the 1,200-man landing party were prevented from disembarking on the wooded shores outside the city by French-Canadian soldiers and First Nations warriors who fired at them from concealment in the trees. Meanwhile, Phips’ three main warships barraged the city with cannon fire, only to be pounded in turn by Quebec’s shore batteries which exceeded them in firepower. Following a futile attempt to overcome the French shore defensives, the besiegers returned to Boston in defeat.

In the years that followed Phips’ failed assault on Quebec, a number of battles between the French and the English and their respective First Nations allies took place in the borderlands between Acadia and New England. Benjamin Church launched two more offensives into what is now Maine, New English sailors made another assault on Port Royal, and French and English mariners engaged in a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy.

In 1696, the French and their native allies captured Fort William Henry, a large stone fortress situated near what is now Bristol, Maine, which had been built on the orders of Sir William Phips. The attackers returned up the Atlantic Coast and preceded to destroy nearly every English settlement in Newfoundland. In response, Benjamin Church led a number of brutal raids on Mi’kmaq and Acadian settlements throughout what is now the province of New Brunswick.

The Nine Years War finally ended in 1697, and its belligerents signed the Treaty of Ryswick- a document which, among other things, restored the pre-war borders in North America. Peace would reign in Acadia for another four years, until the death of the heirless Spanish king and the subsequent War of Spanish success, but that’s a story for another time.

Thanks for Reading!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Kevin Banks

Mr. Peters, what is your comment on the fact that they are drilling inside the footprint of the refilled Hedden shaft (as seen on screen in this episode), and 125′ happens to be the depth of that shaft, as well as the depth that they find undisturbed earth? Also, your diagram of the cross-section of the digging seems to erroneously paint a picture that the Dunfield pit is in the same area of the core holes, specifically FG12, F13, and don’t forget G10.5. They do not intersect with any part of the 1965 Dunfield MP or subsequent cave-in.

Hammerson Peters

I wish I knew where the newer boreholes and the older pits and shafts lay in relation to one another. What makes you confident that the newer boreholes don’t overlap with the Dunfield pit?