The Curse of Oak Island: Season 6, Episode 8- Unearthed

The following is a Plot Summary and Analysis of Season 6, Episode 8 of the History Channel’s TV series The Curse of Oak Island.

[SPOILER ALERT!]

Plot Summary

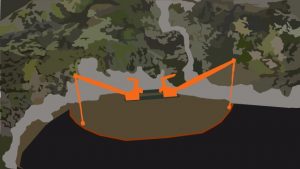

The episode begins at Smith’s Cove, where the Lagina brothers and Craig Tester watch heavy equipment operator Billy Gerhardt excavate the cofferdammed area with a backhoe. Gerhardt quickly unearths a log, which Tester suspects is a component of the cofferdam that Dan Blankenship built around Smith’s Cove in the 1970s.

While Gerhardt works, Gary Drayton sifts through some of the Smith’s Cove spoils he has excavated, which have been rinsed and shaken by the wash plant acquired the previous episode. He discovers a piece of broken pottery among the rocks.

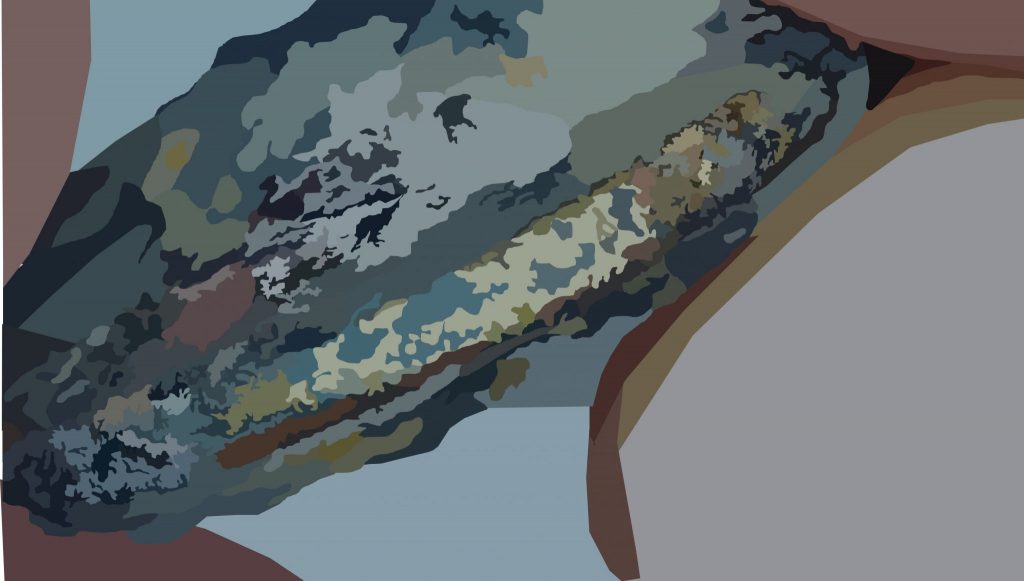

Later, Laird Niven meets with Jack Begley, Charles Barkhouse, Doug Crowell, and Paul Troutman at the Oak Island Research Centre. There, the treasure hunters show the archaeologist the suspected 90-foot stone discovered the previous episode. Niven opines that the letters ‘L’ and ‘N’, with which the stone was inscribed, appear to have been carved with a knife, and ventures that the stone’s smooth faces may have been polished. He then suggests that the team use LIDAR scanning technology (LIDAR being an acronym for “light detecting and ranging”) to make a 3D model of the stone’s surface in order to make out any other inscriptions that are invisible to the naked eye.

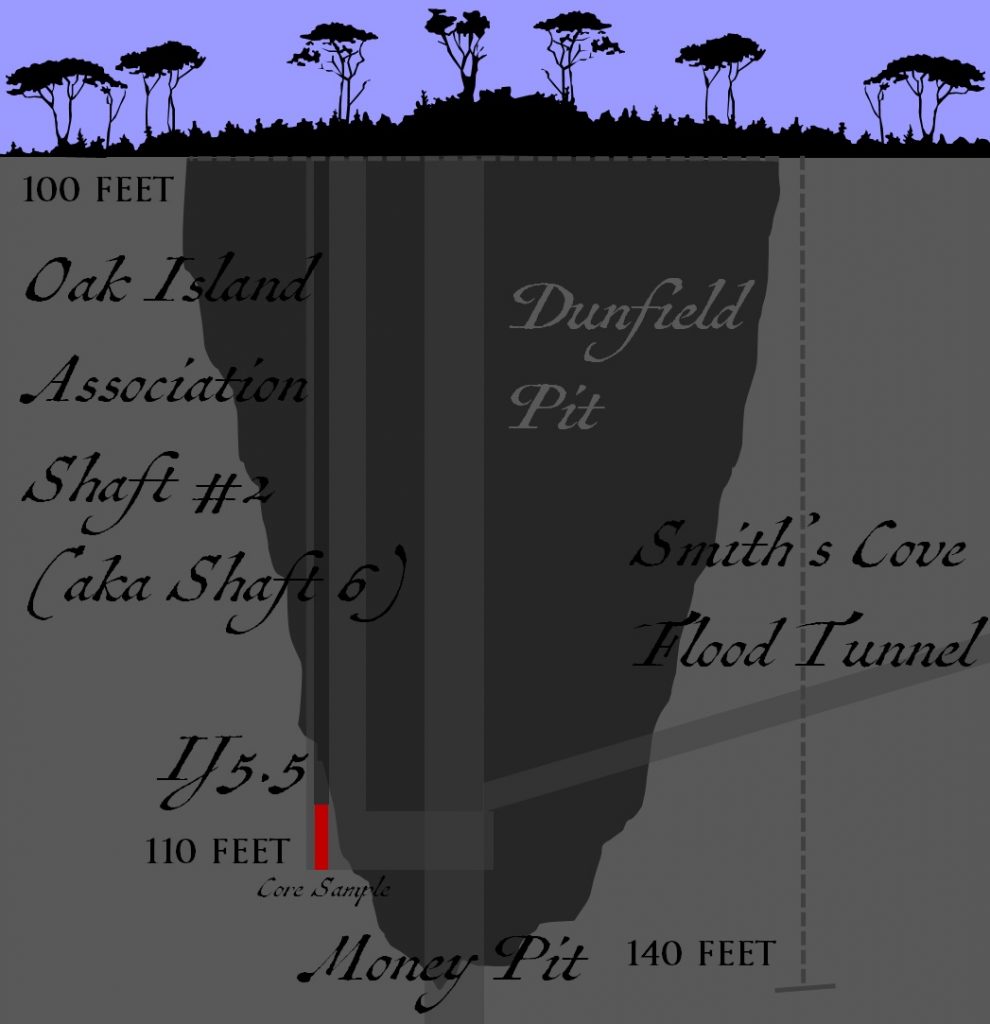

Later, Rick Lagina, Dave Blankenship, Charles Barkhouse, and Doug Crowell head to the Money Pit area, where Choice Drilling is in the process of attempting to determine the orientation of the suspected Shaft 6 Tunnel discovered in Season 6, Episode 5, via exploration drilling. The drillers bring up a core sample from the depths of 108-118 feet and find that it does not contain any wood. This discovery indicates that the hole beside which this new hole was drilled probably failed to intersect the Shaft 6 Tunnel as hoped. As the team prepares the wrap up the operation, Terry Matheson suddenly discovers a piece of wood which appears to be vertically aligned- perhaps the westernmost edge of the Shaft 6 tunnel. The team decides that they ought to drill another hole to the east, hoping to follow the suspected tunnel to the original Money Pit.

The next day, Rob Hyslop and Ryan Levangie of Halifax-based 3D scanning company Azimuth Consulting Ltd. meet with members of the Oak Island team in the Oak Island Research Centre. After some pleasantries, Hyslop and Levangie unpack their Trimble CX 3D laser scanner and proceed to scan the stone. The scan is a success, and Hyslop and Levangie leave the Research Centre with a promise to return with their findings.

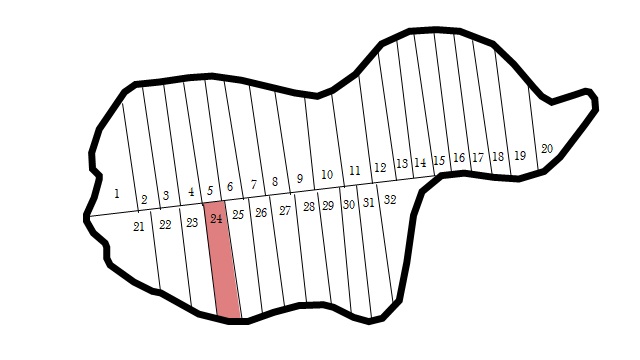

Later that day, Rick and Marty Lagina and Laird Niven head to the area on Lot 24 at which Gary Drayton discovered a number of interesting artifacts the previous episode. Although Rick immediately leaves to attend to other business, Marty watches as Niven forms an archaeological-style grid and begins to excavate the stone-covered area with a trowel. In the same water-filled hole in which Drayton found his artifacts, Niven fishes out a fragment of broken earthenware and a piece of a clay pipe stem. When Niven estimates the latter artifact to date from 1750-1840, Marty says, “I think that we’re looking at something that has to do with Mr. Samuel Ball.” Niven appears to agree, stating that bed of stones which carpet the area “still [have] potential as a cellar”.

Later that day, the Oak Island team throws itself wholeheartedly into the excavation of Smith’s Cove. After searching through some of the spoils extracted by Billy Gerhardt and processed by the wash plant, Gary Drayton discovers an 18th Century iron spike. Shortly thereafter, he digs up what appears to be a gold-plated coin, its faces heavily encrusted with hard-packed dirt. The treasure hunters examine the object and determine that its edges do not appear to be “milled”, whereupon the narrator informs us that, in order to combat the practice of “clipping” (shaving small amounts of precious metal from the edge of coins), the British Royal Mint began to produce coins with ridged edges in the late 17th Century.

That afternoon, Drayton, Craig Tester, and the Lagina brothers head to the Oak Island Research Centre and show their new find to Paul Troutman. Troutman examines the artifact under a microscope. Sure enough, the object appears to be gold-plated. The treasure hunters agree that they ought to carefully remove the sediment that encrusts it so that they might determine the nature of the artifact.

The treasure hunters then proceed with Smith’s Cove and continue with the excavation operation. Using a backhoe, Billy Gerhardt uncovers a wooden beam, which Craig Tester suspects might be an arm of the mysterious U-shaped structure. Rick Lagina and Jack Begley uncover more of this beam with shovels, revealing the Roman numeral “VII” notched into its upper face- an indication that the beam is, indeed, a component of the U-shaped structure.

The Oak Island crew uncovers more of the structure, revealing the Roman numeral “III” and “IV” carved into another beam.

“Is this searcher or depositor?” asks Jack Begley.

“Trying to figure it out,” replies Craig Tester.

Analysis

LIDAR Technology

In this episode, Rob Hyslop and Ryan Levangie of Azimuth Consulting Ltd. use LIDAR technology to create a three-dimensional map of the suspected 90-foot stone discovered in Season 6, Episode 7. In this procedure, they used a Trimble CX 3D scanner to shoot pulses of laser light at the stone and measure the speed and wavelengths of the light that reflected back to the device. Using the data from this survey, they created a 3D model of the stone, the findings from which have yet to be revealed.

Milled Coins

In this episode, Gary Drayton discovered a gold-plated, sediment encrusted coin in Smith’s Cove. The Lagina brothers observed that this object does not appear to bear the markings of a milled coin, which Drayton explained was an indication that the object, if it is indeed a coin, is probably very old.

Until the mid-1500s, most European coins were hammered. In this procedure, blank metal discs were placed between two dies, the upper one bearing the image of the monarch under whose authority the coins were minted and the lower one anchored in a sturdy surface. That accomplished, the upper die was struck with a hammer, impressing both images into the coin.

Coins struck in this manner could be easily “clipped”, clipping being the unscrupulous practice of shaving small portions of precious metal from the edge of the coin and then using the lighter coin as if it retained the same value as the original.

In the mid-16th Century, various royal mints throughout Europe began to machine their coins rather than hammer them. By the end of the 1700s, mints around the world began using machines to “mill” or “reed” their coins, creating adornments along their edges in order to discourage clipping, as an absence of these adornments in milled coins instantly identified them as having been clipped, and therefore worth less than their face value.

Since the coin found in Smith’s Cove does not appear to have been milled, it seems likely that it was struck prior to the late 1700s, when milled coins became the norm throughout much of the Western world.

Want to Help?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please consider checking out our online bookshop:

Leave a Reply