The Curse of Oak Island- Season 5, Episode 3: Obstruction

The following is a Plot Summary and Analysis of Season 5, Episode 3 of the History Channel’s TV series The Curse of Oak Island.

.

.

[SPOILER ALERT!!!]

.

.

Plot Summary

At the Money Pit area, Craig Tester and Jack Begley meet with geologist Terry Matheson and driller Mike Gudelwicz in order see how the pattern drilling operation is progressing. The treasure hunters learn that Brewster Drilling, the contractors they hired for the job, have finished drilling ten exploratory holes in the Money Pit area, none of which have yielded items of especial interest.

Meanwhile, Rick and Marty Lagina accompany metal detection expert Gary Drayton to Oak Island’s Lot 16, where they hope to uncover evidence of pre-1795 activity. In an interview, Rick explains that this lot is the site at which former Oak Island treasure hunter Robert Dunfield, while digging an enormous crater in the Money Pit area in the mid-late 1960’s, dumped much of the spoils.

The three treasure hunters are joined by Dave Blankenship, who instructs them to “find something shiny and gold.” Instead, Drayton unearths “a bloody modern nail.”

“Quit finding that sh**, Gary, and find something good,” admonishes Blankenship, to which Drayton replies, “I say we move away from this dastardly area.”

Drayton starts metal detecting in another area of Lot 16 and quickly unearths what appear to be two 17th Century British coins, the head of one of which Drayton confidently identifies as likeness of King Charles II of England. Drayton becomes even more confident in his assertion when he sees the word “CAROLVS” clearly inscribed on the coin’s edge. The narrator then gives us a brief history lesson on the 1660 Restoration, in which Charles II reclaimed the thrones of England, Ireland, and Scotland from Puritanical dictator Richard Cromwell, Lord Protector of a short-lived British republic called the English Commonwealth. He also informs us that British coins struck under Charles II’s rule bore the Latinized version of his Christian name: “CAROLVUS” (pronounced “Carolus”).

As Drayton studies one of the coins, he remarks that they are the only 17th Century British coins that the men of Oak Island Tours Inc. have recovered on Oak Island. “Marty, maybe I am good luck,” says Dave Blankenship, in response to a quip made earlier in the episode. “You’re goddang right you’re good luck!” replies the younger Lagina brother.

Rick takes a closer look at one of the coins and suggests that the date inscribed on it is ‘1673.’ Marty, who is examining the other coin, suggests that the date on his is ‘1694.’ The four treasure hunters proceed to discuss the significance of the find. All agree that the presence of 17th Century British coins in Oak Island is very unusual, especially when considered in conjunction with the 17th Century Spanish coin unearthed in the Oak Island swamp; the British Crown and Spanish Empire were great rivals in the 1600’s. Drayton remarks that the presence of contemporaneous British and Spanish coins on the island is congruent with the theory that the Money Pit was constructed by pirates, perhaps by the crew of pirate captain William Kidd. The narrator then reminds us of the infamous Wilkins map- a treasure map vaguely resembling Oak Island, which journalist Harold T. Wilkins included in his 1935 historical fiction Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island. Wilkins claimed to have based this map on his memory of two treasure maps allegedly drawn by Captain Kidd.

The Lagina brothers, Dave Blankenship, and Gary Drayton head over to the home of Dan Blankenship to show the elderly treasure hunter their find. Upon looking the coins over, Dan says that they give credence to the foundational theory, upon which all other Oak Island theories are based, that something significant happened on Oak Island prior to 1795- a theory which he hoped to authenticate when he first set foot on the island in 1965. “Hopefully this is just the beginning,” says Drayton.

Later, Rick and Marty Lagina, Craig Tester, and Jack Begley congregate at the Money Pit area, where the pattern drilling operation is underway. At a depth of 162 feet, the drill encounters a hard object which, when brought to the surface, is revealed to be a thick chunk of steel. The narrator suggests that this piece of metal might be a fragment of the impenetrable iron object encountered by driller William Chappell in 1897. Immediately afterwards, the drill grinds to a halt, having encountered another such object. The team decides to bring the drill up and case the hole with PVC pipe. “I’m not dismayed at all,” says Rick of the development in a later interview. “That’s the reason for the grid, you know? We may find it in the first hole, we may find it in the thirty seventh hole. We’ll find it.”

The next morning, Marty Lagina and Craig Tester drive to Dave Blankenship’s home in response to an ominous summons by Rick. On the way, Craig explains that Rick received a letter from Nova Scotia’s Department of Communities, Culture, and Heritage (CCH; a department of Nova Scotia’s provincial government) and that he likely wants to talk about it.

At Dave’s house, Dave and Rick hand Marty and Craig copies of the letter, the author of which expresses concern that “metal detecting on the island has the potential to impact existing archaeological sites and resources,” and stipulates that Oak Island Tours Inc. may continue to carry out such operations only under the supervision of an archaeologist. The letter goes on to inform the treasure hunters that they are henceforth precluded from further “excavation or removal of objects,” and may only continue such work under a Heritage Research Permit. In unison, the Lagina brothers agree that the stipulations outlined in this letter constitute the first step “in shutting own the whole island.”

The Lagina brothers discuss the implications of this letter in a later interview. “The metal detection has provided lots of clues to what might have happened here,” says Marty, “and it’s continuing to. So we’re very upset, very upset about this. The clue that we need could be out there to be metal detected, and we’ll never find it under this protocol.” Rick follows up on his brother’s statement, saying, “It’s not just the concerns they’ve expressed; they’ve given us parameters under which we can no longer proceed, in our opinion.” “It’s very chilling to the exploration efforts out here,” concludes Mary. “We just don’t get it.”

Back in Dave Blankenship’s home, the treasure hunters express their frustration with this latest development, and agree that a face-to-face meeting with a representative of CCH is in order.

The following day, the Oak Island team congregates at Old Mader’s Wharf Emporium, a restaurant in Mahone Bay, where Rick and Marty fill them in on a meeting they just had with Nova Scotia’s Minister of Culture and Heritage. Although they were unsuccessful in lifting the newly-imposed restrictions, they learned that the CCH was likely acting in response to pressure put on them by the archaeological community. They also proposed a compromise in which they would hire an archaeologist, who would get a blanket Heritage Research Permit which would allow them to excavate and extract artifacts from the island as they please (as opposed to applying for a Heritage Research Permit every time they wanted to excavate or unearth an artifact). The CCH apparently accepted this proposal. The team decides to hire Laird Niven, an archaeologist with whom they worked in the past.

The next day, Rick and Marty Lagina and Craig Tester meet with Laird Niven at the Oak Island Visitors’ Centre. There, the treasure hunters show the archaeologist some of the artifacts they have unearthed on Oak Island and ask him if he is interested in working with them. Niven accepts the job, saying that he will apply for a Heritage Research Permit immediately.

The following day, Rick and Marty Lagina, Gary Drayton, and Laird Niven head to Oak Island’s Lot 24, the former residence of Samuel Ball. There, the decide to uproot a number of trees with a backhoe in the hope that items of interest might lie beneath. Beneath the first tree they uproot, Drayton discovers the bowl of a spoon which Niven believes is an 18th Century artifact. They proceed to dig up several more trees, under one of which they unearth a large chunk of iron, which Niven suggests might be the rusted remains of a door hinge.

When Marty, in the backhoe, uproots yet another tree, Niven calls a stop to the excavation out of concern that the large stones exposed beneath it might be of cultural significance. The archaeologist jumps into the cavity to examine the stones, and decrees that the team cannot continue digging there. Gary Drayton, with Niven’s permission, examines the roots of the extracted tree with a metal detector and discovers a piece of pewter, which Niven claims is part of a spoon bowl.

When Marty asks Niven what procedure they should follow, the archaeologists says that they ought to “clean up the loose soil” in the cavity in order to determine if the rocks indeed constitute the remains of some sort of artificial structure.

Analysis

The Wilkins Map

In this episode, the narrator briefly mentions the ‘Wilkins Map’ in connection with the theory that pirate Captain Kidd was the man responsible for Oak Island’s underground workings. The following is a description of this strange document, around which revolves one of the most bizarre chapters in the history of the Oak Island treasure hunt.

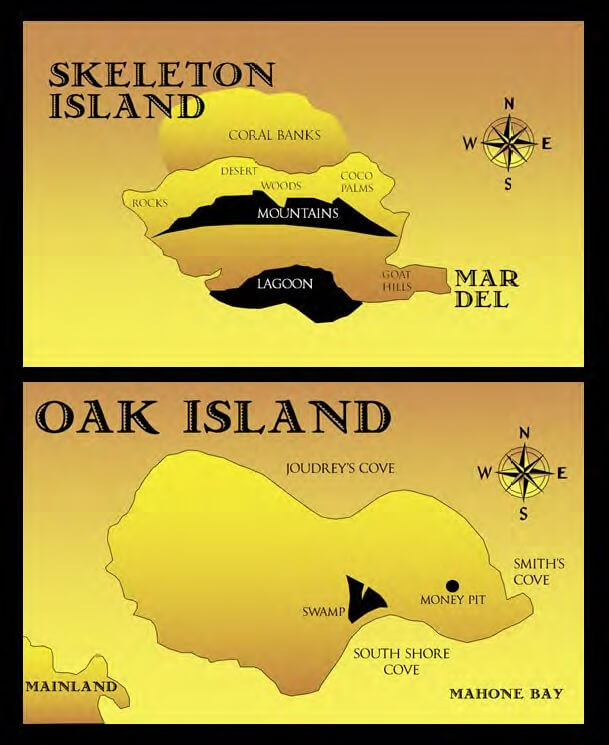

In 1935, a British journalist named Harold T. Wilkins had his fourth book published. Wilkins’ work, Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island, is a historical fiction book about pirates, buried treasure, and “the discovery of a strange secret hid for 226 years.” In the book is the picture of an authentic-looking, hand-drawn treasure map depicting an island vaguely suggestive of Oak Island.

In the summer of 1937, R. V. Harris, a lawyer from Halifax, Nova Scotia, who worked for both Fredrick Blair (Oak Island’s contemporary landowner) and Gilbert Hedden (the man who owned Oak Island Treasure Trove Licence at the time), discovered the map in Wilkins’ book and showed it to Hedden. The New Jersey treasure hunter was astonished; to him, Wilkins’ map bore an uncanny resemblance to Oak Island. Hedden studied the map more thoroughly and picked out enough similarities between it and Oak Island- including coves roughly congruent with Joudrey’s Cove, Smith’s Cove, and the South Shore Cove, along with a lagoon eerily similar to Oak Island’s swamp- to become convinced that it might, in fact, be a real Oak Island treasure map drawn up by the original Money Pit builders. Even more fascinating was the fact that the map contained directions leading to the location at which the treasure lay buried. Intrigued, Hedden sent a letter to Harold Wilkins, hoping to learn where and how he had come across such an artifact.

Wilkins sent a letter back to Hedden assuring him that the treasure map in his book was not a map of Oak Island, but rather a depiction of an island in some “eastern sea” far from the Atlantic. Aside from that admission, however, he remained curiously tight-lipped about the treasure map’s origins and how he had discovered it.

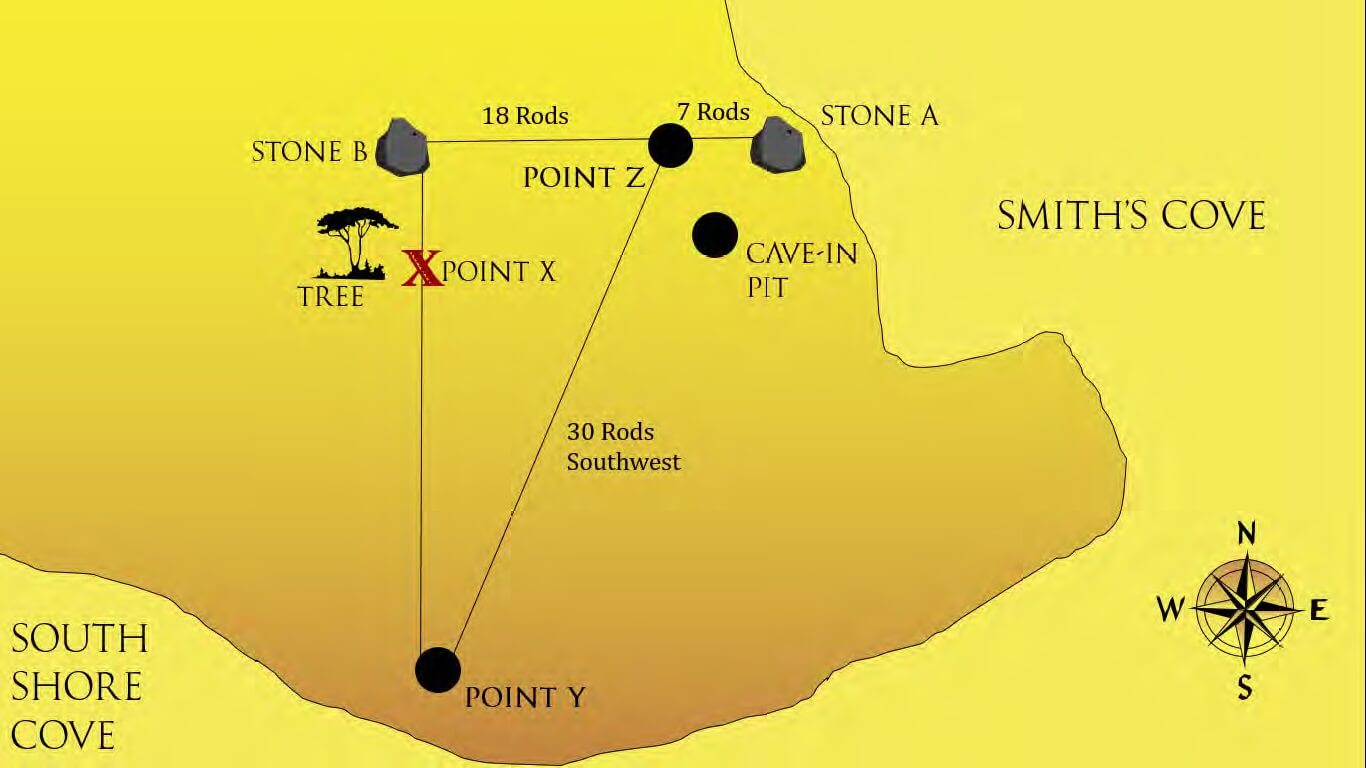

Hedden was unconvinced, believing that the similarities between Wilkins’ map and Oak Island were too great to be coincidence. Accordingly, he turned his attention towards the directions at the bottom of the map, which read:

“18 W. and by 7 E. on Rock

30 SW. 14 N Tree

7 By 8 By 4”

The first line of directions seemed to suggest that that first step in the treasure hunt was to locate some sort of prominent ‘Rock’, probably situated on the beach somewhere near the spot at which treasure hunters would be most likely to disembark. In the case of Oak Island, that beach was probably Smith’s Cove, the section of Oak Island

beach most exposed to the ocean. Interestingly, Frederick Blair, during a conversation with Hedden on

this subject, vaguely recalled hearing about two mysterious drilled rocks discovered by earlier Oak Island treasure hunters, one of which lay on the shores of Smith’s Cove. Hedden had his crew search for these stones, and sure enough, a rock with a 2-inch-deep, 1- inch-diameter, obviously-man-made hole in it was discovered at Smith’s Cove. We’ll call this rock Stone A. Another rock with a similar drill hole was found about fifty feet north of the Money Pit. We’ll call this one Stone B.

Upon discovering the stones, Hedden, who had a bit of an engineering background, believed that the first line of directions indicated a point on the line between Stone A and Stone B, as seen on a topographical map. We’ll call this Point Z. Point Z would be 18 units east of Stone B and 7 units west of Stone A. This would make the distance between Stone A and Stone B 25 units in total (18+7). Since the distance between the two drilled rocks was 415 feet, each unit would roughly equal 16.5 feet (415/25). Interestingly, 16.5 feet is equal to 1 rod, an old English unit of measurement.

After making this tantalizing discovery, Hedden focused his attention on the second line of directions. He theorized that the first part of this line, “30 SW,” indicated a point 30 rods (495 feet) southwest of Point Z. We’ll call this Point Y. The second part of the line, “14 N Tree,” possibly referred to a point 14 rods (231 feet) north of Point Y, at which stood a tree. Perhaps this was the oak tree discovered by Daniel McGinnis, John Smith, and Anthony Vaughan in 1795, from which’s branch was suspended a block and tackle directly over the Money Pit. We’ll call this Point X; X marks the spot.

After making some calculations, Hedden had his crew search for Point Z, which was 297 feet (18 x 16.5) east of Stone B and 115.5 feet (7 x 16.5) west of Stone A. Although nothing of interest was discovered at that particular point, the Cave-In Pit was located a short distance away.

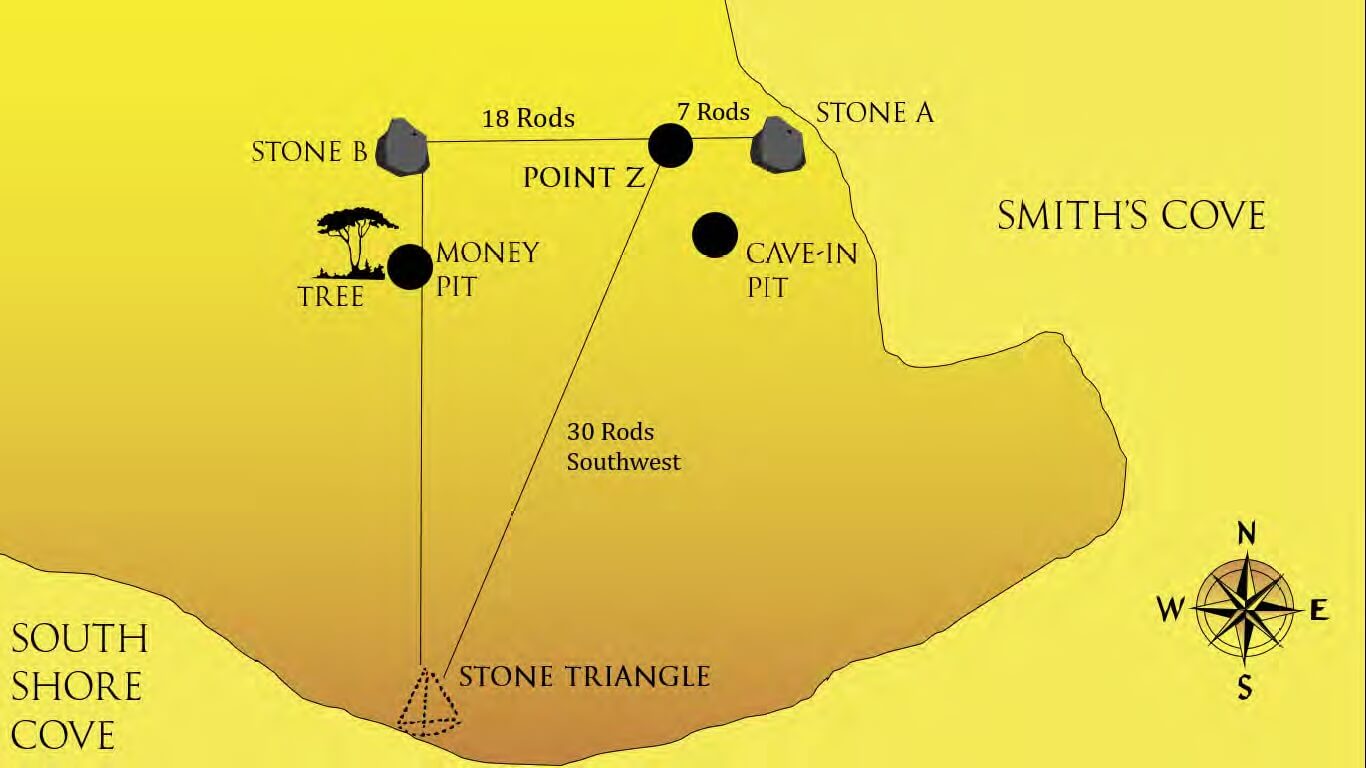

Next, Hedden had one of his employees, Amos Nauss, search the underbrush on the southeastern end of Oak Island, in the general vicinity of Point Y. In Nauss’ words:

“Hedden gave me some idea that there was something down there at the beach that he wanted to find. So I explored around there with a hoe. I was clawing around and suddenly I hit one rock, then another and another, all in line with each other. So I decided there was something there, and I started clearing it and called Hedden over.”

Nauss had rediscovered the stone triangle, first discovered by Captain John Welling of Frederick Blair’s Oak Island Treasure Company in 1897, and later rediscovered by Mel Chappell a few years earlier in the spring of 1931. The base of the 10-foot equilateral triangle was 10 feet north of Point Y. Interestingly, the base was also exactly 30 rods (495 feet) southwest of the centre of the Cave-In Pit.

Although the Oak Island landmarks did not exactly match the Wilkins’ map directions, Hedden was certain that he was onto something. The treasure hunter asked Charles Roper, a surveyor from Halifax, to investigate his finds. Roper provided Hedden with the precise measurements between the various Oak Island landmarks, and informed the treasure hunter that the stone triangle appeared to point due north, directly towards the Money Pit area. However, upon measuring, Roper and Hedden learned that the Money Pit area was only roughly 10 rods (165 feet) north of the stone triangle, not 14 rods as the Wilkins’ map apparently suggested.

Hedden was never able to reconcile the last line of Wilkins’ treasure map instruction with any group of Oak Island landmarks.

While searching for more landmarks which might correspond with Wilkins’ map, Hedden discovered “an old dump… in which are [were] the remains of thousands of broken pottery flasks” on Joudrey’s Cove. Nearby these pottery shards was “an old coin and an ivory boatswain’s whistle…”

In the aftermath of Roper’s survey, Hedden was convinced more than ever that the map in Wilkins’ book was a real treasure map depicting Oak Island. He decided to travel to England and meet with Harold Wilkins in person. When Hedden informed Wilkins of his intentions, the journalist wrote back that he was willing to meet with the treasure hunter, but that such a journey would be a waste of time for Hedden, as the map in his book was definitely not an Oak Island treasure map. He also hinted in his letter that the map in his book was actually not an authentic treasure map at all, but rather an “approximate copy” of four genuine 17th Century pirate treasure maps. Nevertheless, Hedden made the trip to England and met with Wilkins in December, 1937. His experience was both strange and discouraging.

Almost immediately after meeting Hedden, the British journalist confessed that the map in his book was, in fact, a diagram of his own devising. While doing research for his book, Wilkins had come across an English antiques dealer named Hubert Palmer who had in his possession four 17th Century charts which he claimed were treasure maps drawn up by the notorious Captain William Kidd, a Scottish privateer who was hanged for piracy on London, England’s Execution Dock in 1701, and who was rumoured to have buried a treasure of enormous value on an unknown island sometime before his demise. Palmer did not allow Wilkins to take photographs of his charts, which all depicted what appeared to be the same island located somewhere in the South China Sea, and so Wilkins settled with committing them to memory as best he could. Using his memory of the charts, the journalist drew his own

treasure map. When his publishers demanded that his map contain instructions on how to locate the treasure for added spice, Wilkins fabricated the three lines of instructions using nothing more than his imagination.

Baffled by the remarkable connection between Wilkins’ ad-libbed treasure hunting instructions and the landmarks on Oak Island, Hedden told the journalist all about the mysterious drilled stones, the stone triangle, the Cave-In Pit, the oak tree believed to have once stood beside of the Money Pit, and the fact that the distance separating these landmarks roughly corresponded with Wilkins’ map’s instructions if measured in old English rods. As Hedden explained the extraordinary coincidence, Wilkins became increasingly convinced that he was the reincarnation of

Baffled by the remarkable connection between Wilkins’ ad-libbed treasure hunting instructions and the landmarks on Oak Island, Hedden told the journalist all about the mysterious drilled stones, the stone triangle, the Cave-In Pit, the oak tree believed to have once stood beside of the Money Pit, and the fact that the distance separating these landmarks roughly corresponded with Wilkins’ map’s instructions if measured in old English rods. As Hedden explained the extraordinary coincidence, Wilkins became increasingly convinced that he was the reincarnation of

a 17th Century pirate, perhaps even Captain Kidd himself, and that his subconscious had conjured up some long-forgotten memory of the map leading to Kidd’s lost treasure, which he was now certain lay buried deep beneath Oak Island. After Wilkins enthusiastically revealed his conviction to Hedden, the latter began to suspect that the journalist was “every bit as crazy as his book would seem to make him,” or perhaps a fraud.

Hedden concluded his business in England, deciding that Wilkins’ map was no longer worth investigating. Instead of returning to Oak Island, he travelled straight to New Jersey, his hometown. There, he sent a letter to his lawyer R.V. Harris explaining that, although he had initially planned to renew his contract with Blair the following spring, he had since run into serious financial difficulties and needed to focus on expanding his company instead of on the Oak Island treasure hunt. When Blair learned of this new development, he was outraged, feeling that Hedden, a fellow Freemason, had betrayed him. The 71-year-old treasure hunter waited for another treasure hunter to take Hedden’s place, and found one in the form of Erwin H. Hamilton.

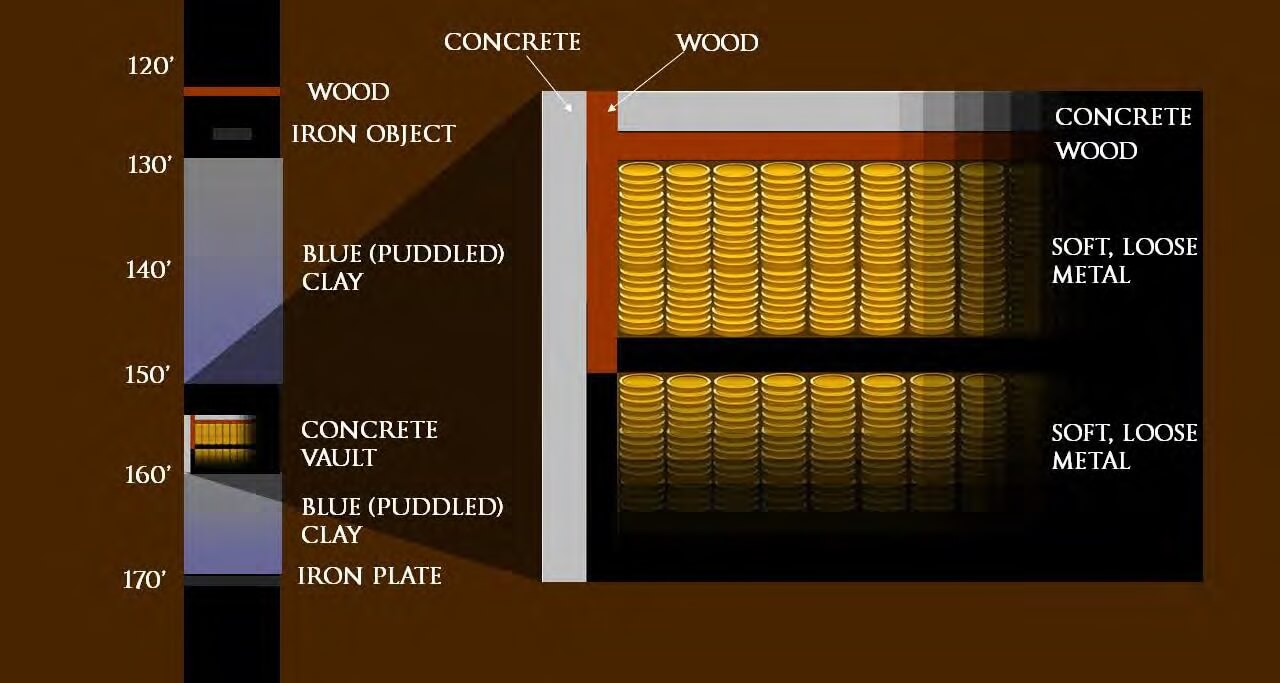

The Impenetrable Iron Object

In this episode, Oak Island Tours Inc., while drilling in the Money Pit area, encountered an impenetrable steel object at a depth of 162 feet. Before Robert Dunfield’s heavy-duty excavation in the Money Pit area, which lowered the surface of the Money Pit area about 10 feet, this object would have been located about 172 feet below the surface. This steel object discovered this episode sharply evokes the impenetrable iron object encountered by driller William Chappell of the Oak Island Treasure Company in the Money Pit in 1897. Chappell encountered this object at a depth of 171 feet.

In the summer of 1897, the Oak Island Treasure Company decided to conduct an exploration drilling operation in the Money Pit. Using steam-powered pumps to keep the flooding in check, the they set up a drilling platform in the Money Pit at the 90-foot level. From there, they prospected the Money Pit to depths never before reached by previous Oak Island treasure hunters. Their findings were some of the most astounding discoveries made on the island to date.

Core samples from the drilling operation revealed a layer of wood at 122 feet and an impenetrable iron object at 126 feet. Below that was a thick layer of blue clay from 130-151 feet. Then, at 154 feet, the drill encountered a 7-inch layer of cement followed by 5 inches of oak. Below that were about 2.5 feet of soft, loose metal, which reappeared again at the 158-foot level. Similar to the Truro Company before them, who, in 1850, located soft, loose metal in the Money Pit at around the 100-foot level, the Oak Island Treasure Company was unable to procure any samples of this substance. At the 160-foot level, the drill encountered another thick layer of blue clay which ended at 171 feet. At the 171-foot level, the drill encountered what appeared to be an impenetrable iron plate. After collecting some shavings of this material by running a magnet over the end of the drill bit, the Oak Island Treasure Company confirmed that the hard substance at the 171-foot level was indeed iron.

The Restoration of King Charles II of England

In this episode, the team unearths two British coins on Oak Island’s Lot 16, dated 1673 and 1694, respectively. This discovery is perhaps most consistent with the theory that Oak Island’s treasure was interred by pirates, possibly the crew of Captain Kidd.

Another theory which the coins sharply evoke is Canadian mining engineers Graham Harris and Les MacPhie’s fascinating argument, outlined in their book Oak Island and its Lost Treasure: The Untold Story of the British Military’s Role in the Island Flood Tunnel (2013), which proposes that the Money Pit was first excavated by the crew of New English treasure hunter Sir William Phips, and that the Smith’s Cove Flood Tunnel was later constructed by a government-sanctioned company composed of British engineers and Cornish miners.

Unfortunately, Harris and MacPhie’s theory, along with its historical context, it is far too elaborate to detail in this article. Somewhat less comprehensive, however, is a description of the prequel to the historical stage on which their theory is set- a turbulent period of English history, outlined briefly in this episode, known as the Restoration.

The Restoration has its roots in the Protestant Reformation, a series of schisms in the Roman Catholic Church which occurred throughout the 16th Century, initiated by Protestant Reformers such as Martin Luther, who founded Lutheranism; John Calvin, who founded Calvinism; and King Henry VIII of England, who founded Anglicanism (a.k.a. The Church of England). These schisms resulted in a series of bloody religious wars fought throughout the 17th Century.

By the 1600’s, nearly all of England was Protestant. The nation, in general, feared and despised Catholicism, and was characterized by a paranoia that subversive Catholic agents were constantly conniving to reinstitute the old religion. At the same time, England’s Protestants were divided into Anglicans and Puritans, Puritanism being an offshoot of the Church of England which held that the ceremonial use of religious objects- a Catholic-like practice employed by Anglicans- was tantamount to idolatry. In spite of their ideological incompatibilities, adherents to these two disparate doctrines coexisted relatively peacefully for a number of decades.

France was not immune to the religious turmoil of the 17th Century. Although most of the country remained staunchly Catholic, a branch of French Calvinists called Huguenots revolted against royal authority in a series of conflicts known as the Huguenot Rebellions. The last of these rebellions, fought from 1626-1629, culminated in the Siege of La Rochelle, a Huguenot stronghold on the west coast of France (this battle is the historical event around which Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers revolves).

During the Siege of La Rochelle, King Charles I of England, on the advice of his most trusted advisor, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, decided to assist his fellow Protestants and join the fight against the French. In order to do this, he would need to secure some serious capital, and in 17th Century England, the only way for the Crown to collect significant tax revenue was through the use of an institution called the Parliament.

Unfortunately, Charles I and the Parliament did not see eye to eye. The king’s wife, a French princess named Henrietta Maria, was a devout Catholic, while the king himself was an Anglican. The English Parliament, on the other hand, was composed predominantly of staunch Puritans. The Parliamentarians loathed the king for his faith and especially that of his wife, and accordingly refused to provide him with the capital he needed to finance his military expedition to La Rochelle.

The king found the capital he needed through other means and tasked the Duke of Buckingham with leading a force to the French port city. Buckingham did as commanded and set sail for France with a complement of 6,000 soldiers. On the French battlefield, the Duke’s forces suffered a series of crippling defeats, and Buckingham returned to England, humiliated.

On August 23, 1628, the Duke of Buckingham was stabbed to death by John Felton, a disgruntled officer under his command. Although evidence indicated that Felton had likely acted on his own, King Charles I strongly believed that Parliament was behind his advisor’s assassination. Accordingly, he dissolved the unhelpful institution, determined to never reinstate it again.

For the next eleven years, Charles I ruled England without recourse to Parliament. The king’s detractors labelled this period the “Eleven Years’ Tyranny.” Since Parliament was the only means by which the monarch could acquire significant capital, King Charles I soon found himself in a financial predicament- a situation exacerbated by the expense incurred by his participation in the 30 Years’ War (a bloody European religious war fought from 1618-1645).

In 1639, King Charles I entered into a religious war with a force of Scottish Presbyterians called Covenanters (Presbyterianism being an offshoot of Calvinism). In order to raise money to finance this war, known as Bishops’ War, the king reluctantly reinstated Parliament. When Parliament predictably refused to comply with his wishes, he promptly dissolved it before reinstating it again a short time later, desperate for capital.

The Parliament took this opportunity to erode the king’s authority bit by bit, raising capital for the king in exchange for heavy concessions. Eventually, Charlies I decided to put an end to the Parliament’s subversion and attempted to arrest five of its Members for high treason. This act sparked a physical conflict between Parliamentarian Puritans (and their Presbyterian Covenanter allies, with whom they shared a common enemy) and Loyalist Anglicans which devolved into an all-out civil war, known today as the English Civil War.

This conflict pitted Puritan “Roundheads,” so called for the shaven pates many of their lowborn ranks affected (which contrasted starkly with the long ringlets worn by members of the aristocracy), against Loyalist “Cavaliers,” so named for their commanders’ resemblance to Spanish Caballeros (mounted knights) in their haughty demeanor and gaudy clothing. Initially, Loyalist forces won a series of victories under the command of Prince Rupert of the Rhine (the namesake of Prince Rupert, BC, and Rupert’s Land, the vast territory once controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company), a dashing young cavalry commander and nephew of the king. However, Prince Rupert met his match at the Battle of Marston Moor, fought on July 2, 1644. There, his army clashed with a much larger Parliamentarian and Covenanter force, which included a dogged, highly disciplined cavalry troop commanded by Oliver Cromwell, a zealous Puritan farmer-turned-military commander. Cromwell’s troops routed the Loyalist cavalry, which turned the tide of battle in Parliamentarian favour and ultimately led to a decisive Roundhead victory.

Oliver Cromwell quickly climbed the ranks to become second in command of the Parliamentarian army. He led his troops to victory a the decisive Battle of Naseby, which ultimately resulted in the capture of King Charles I.

The Parliament agreed to release the king on the condition that he relinquish some of his power to them. The stubborn monarch, however, believing that he had a divine right to rule, refused to give the Puritans any ground. After failing to convince the king to accede to their demands, Oliver Cromwell and the Parliament decided to put Charles I on trial for treason. The English king was ultimately convicted and sentenced to death. On Tuesday, January 20, 1649, King Charles I was beheaded by a single stroke of executioner’s axe at London’s Palace of Whitehall, thereby becoming the only English king to lose his head.

In the wake of the king’s execution, Oliver Cromwell established the Commonwealth of England, Britains first and only republican government. At the behest of his advisors, Cromwell became the Lord Protector of this new regime.

The following year, the Presbyterian Scottish Covenanters turned against their old allies, Oliver Cromwell’s Puritans, on account of religious differences. On September 3, 1650, they faced Cromwell’s republican army, called the New Model Army, at the Battle Dunbar and were soundly defeated. Later that year, in order to legitimize their cause, the Covenanters crowned Charles I’s eldest son, twenty-year-old Charles, who had spent the last half of the English Civil War in exile in France and Holland, King of Scotland. At the instance of the Covenanters, Prince Charles publicly denouncing Catholicism- a religion he inwardly adhered to on account of his mother’s influence- and outwardly converted to Presbyterianism.

In 1651, Charles, determined to retake his father’s crown, launched an invasion into England. This invasion ended in defeat at the Battle of Worcester, fought on September 3, 1651- the anniversary of Cromwell’s victory at Dunbar- and Charles subsequently fled to continental Europe.

On September 3, 1658, 59-year-old Oliver Cromwell succumbed to malaria and kidney disease. He was succeeded as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth by his son, Richard Cromwell. Unlike his zealous father, Richard lacked the full support of the New Model Army and the Parliament, and soon the Commonwealth descended into anarchy.

Charles took advantage of the opportunity and returned to England. On May 25, 1660, he landed at the town of Dover, on the southeast coast of England, accompanied by a Loyalist entourage. The prince made his way to London, greeted along the way by Englishman who were overjoyed by the return of the long-lost heir to the throne. The triumphant Charles- now King Charles II of England, Scotland, and Ireland- rode into the capital on his 30th birthday and reclaimed his crown.

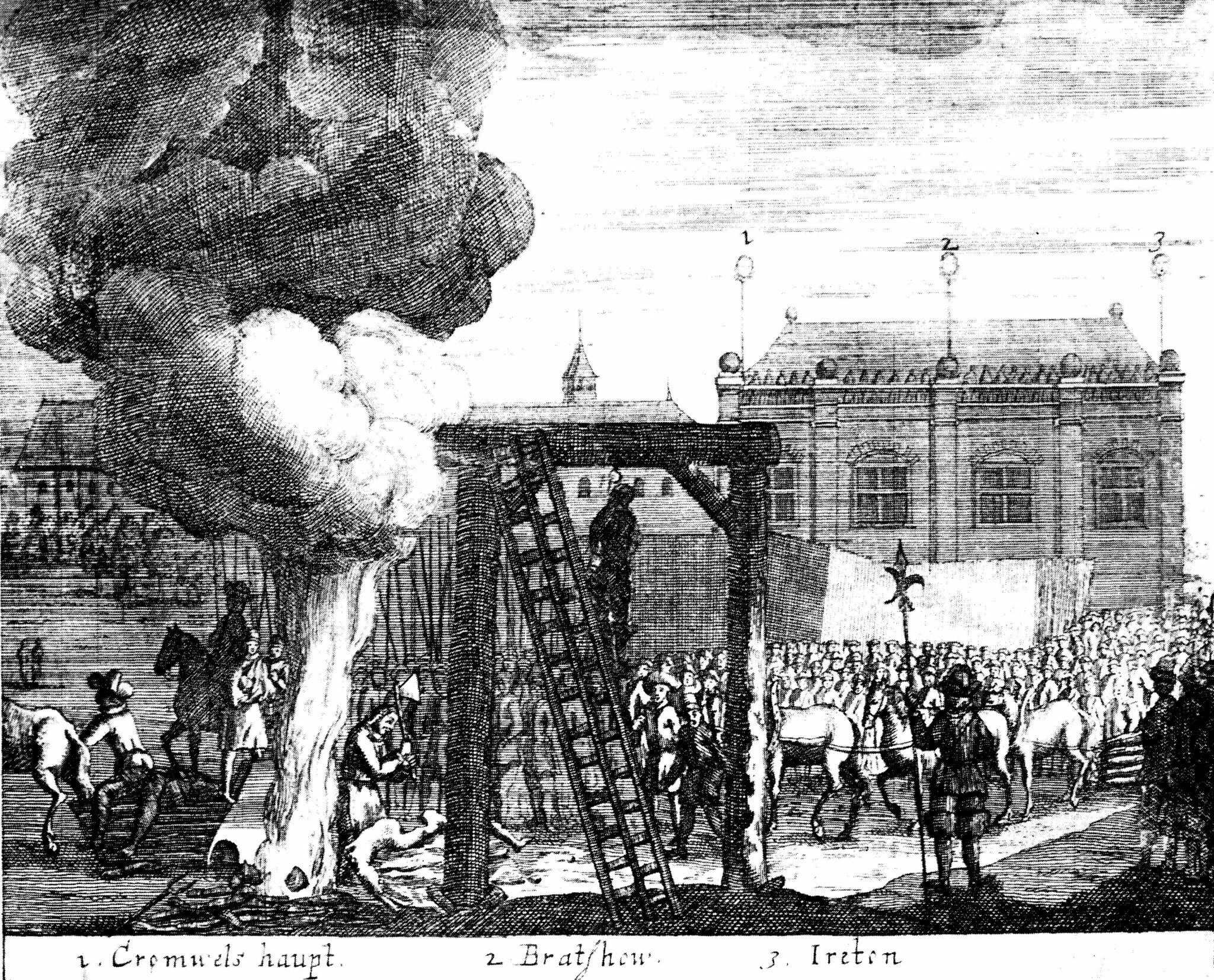

Following his ascension to the throne, Charles II returned many of his father’s old Royalist supporters, including Prince Rupert of the Rhine, to their former offices and rewarded them for their loyalty. Nine of the Parliamentarians who had a role in his father’s regicide, on the other hand, were condemned as traitors and hanged, drawn, and quartered (i.e. submitted to a horrific execution, reserved for traitors, in which they were hanged (almost to the point of death), disemboweled alive, beheaded, and chopped into four pieces). The corpse of Oliver Cromwell was exhumed and posthumously executed; the Puritan’s skeleton was hanged and beheaded, his skull afterwards mounted on a wooden spike and erected above Westminster Hall.

This event, in which monarchy returned to England, is known today as the English Restoration.

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

Leave a Reply