Congratulations!

Congratulations! If you’re reading this, you probably solved the puzzle I left on my YouTube video on the Rosicrucian theory of Oak Island. Well done; I’m very impressed.

I directed you here because I want to tell you something that could be dangerous to say on YouTube. Things are rapidly getting weird in the YouTube world, and I’m not a fan of the changes. Over the past few weeks, I’ve seen a ton of comments disappear from my videos. Many of them were very interesting, thoughtful, or humorous. Others I didn’t exactly agree with. But all of them were quite innocuous, no matter how you sliced them. One viewer, for example, attributed the apparent clairvoyance of NWMP scout Jerry Potts to “the power of the whisky” of which he was notoriously fond. Another suggested that Freydis Eriksdottir, a Norse explorer who had some of her kinsmen massacred on false charges, must be the ancestor of a certain American politician whose name rhymes with “Pillory Swinton”. Two more made comments regarding the supposed racist nature of a coureur de bois who features in my video on the werewolf legends of French Canada.

I am NOT deleting these comments; I think YouTube is deleting them automatically. For the record, I don’t believe in censorship, and avoid deleting comments on my own channel except in very special circumstances (ex. I’ve deleted comments constituting private conversations with people I know personally, who apparently forgot how email works). YouTube, on the other hand, appears to be censoring any comments which its algorithm considers offensive, which apparently include comments containing words like “whisky”, “racism”, or the aforementioned American politician.

I want my viewers to be able to express themselves without fear of censorship, and so I thought I’d let you know that, in addition to YouTube, I’m also uploading my videos to the free speech-oriented video platform Rumble; you can find my Rumble channel here. In the event that YouTube decides to remove my channel from its platform one day, I’ll still be doing my thing over there.

Thank you so much for reading, and for taking the time to solve my puzzle! Please feel free to leave a comment below declaring that you’ve cracked the code. You’ve earned it!

Sincerely,

HP

….

The Curse of Oak Island– Season 4, Episode 4: No Stone Unturned

This week’s episode of The Curse of Oak Island requires a good deal of unpacking. Names were introduced, discoveries were alluded to, and artifacts were presented with as much backstory as the 42-minute program would allow (i.e. not a heck of a lot). Without further ado, here is a Plot Summary and Analysis of Season 4, Episode 4: No Stone Unturned.

***SPOILER ALERT***

Plot Summary

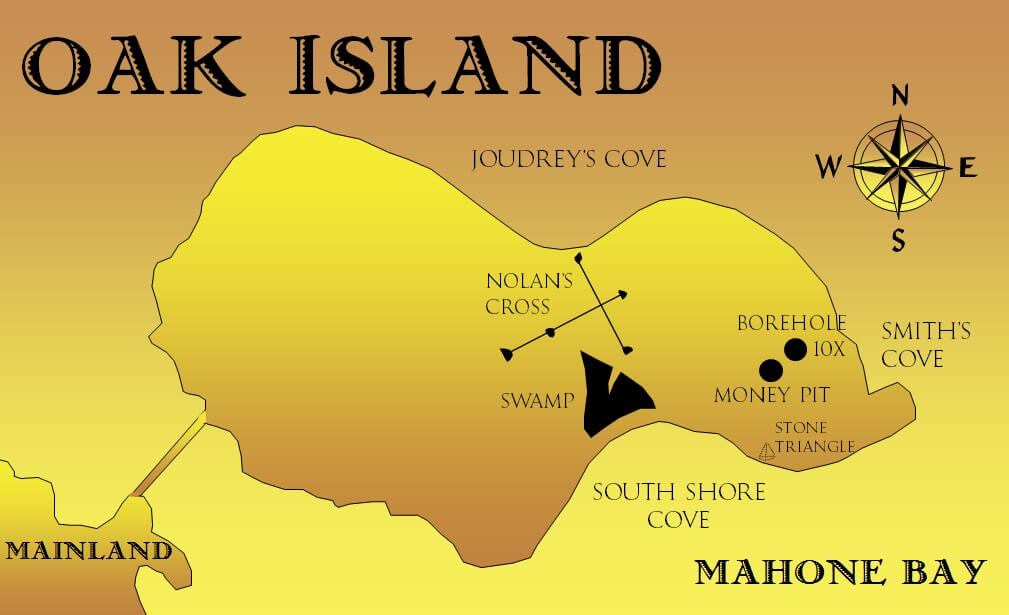

Rick and Marty Lagina, Marty’s son Alex, the Laginas’ nephew Peter Fornetti, Dan and Dave Blankenship, Jack Begley, and Charles Barkhouse watch as Mike Turnbull and Andrew Folkins of Irving Equipment Ltd. drive across the causeway to Oak Island, their 18-wheeler laden with high-tech excavation equipment. With this equipment, the Oak Island crew plans to fully excavate the Money Pit and solve the Oak Island riddle once and for all.

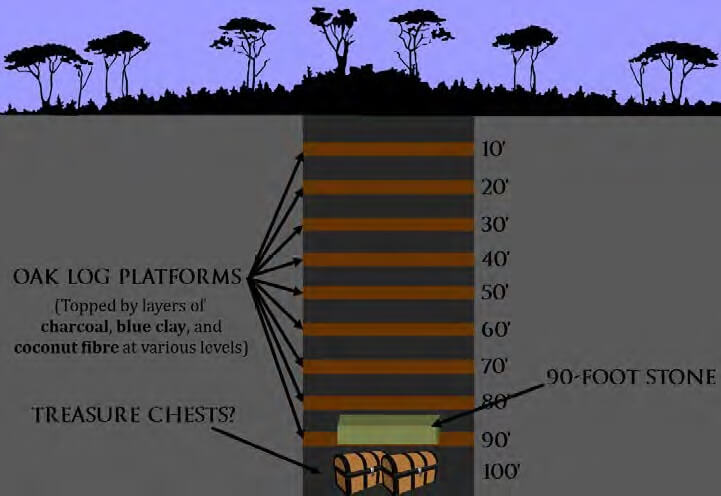

The narrator explains that the two areas of interest in the vicinity of the Money Pit which Oak Island Tours Inc. plans to excavate are the sites of drill holes labelled ‘Valley 3’ and ‘C1’, respectively. Valley 3 is the hole drilled in The Curse of Oak Island’s Season 2, Episode 4, in which clay, two perpendicularly-oriented fragments of old oak wood, and a substance which is either natural limestone or crude artificial concrete were found between the depths of 140 and 142 feet. The Oak Island crew speculated that Valley 3 might have intersected a concrete treasure vault believed to have been discovered by driller William Chappell in 1897. They named this hypothetical vault the ‘Tester Vault’ in honour of their fellow treasure hunter Craig Tester, the engineer who prescribed the drill hole upon analyzing archival maps.

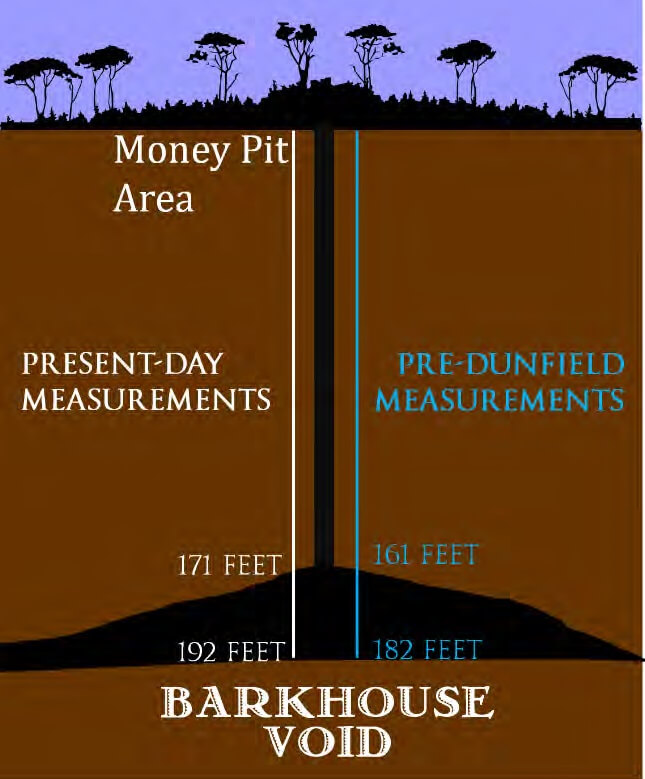

The other drill hole, C1, was bored in the TV show’s Season 3, Episode 12 on the advice of Oak Island historian Charles Barkhouse. This hole encountered a 21-foot void beginning at a depth of 171 feet. The following episode, a special camera revealed the presence what appeared to be a shiny gold-coloured object at depth.

After hearing veteran Oak Island treasure hunter Dan Blankenship express his desire to see the Oak Island mystery solved, the Oak Island crew meet in the War Room, where Oak Island researchers and historians Doug Crowell and Kel Hancock of Blockhouse Investigations inform them that they have identified the location at which Oak Island’s semi-legendary 90-foot stone was last scene: a building in Halifax which once housed a bookbindery called Creighton & Marshall Stationers. The narrator then describes how the stone was discovered at the 90-foot depth in the Money Pit in 1804, transported off the island in 1865, and eventually put on display in the front window of Halifax’s Creighton & Marshall Stationers. The narrator goes on to explain how the stone mysterious disappeared in the 1930’s, and how various Oak Island enthusiasts have been searching for it ever since.

Following the narrator’s explanation, Rick Lagina mentions that the last documented sighting of the stone was in 1909, when Oak Island treasure hunter Harry L. Bowdoin examined it. The narrator then briefly describes the American treasure hunter, his remarkably unproductive stint on Oak Island, and his visit to Creighton & Marshall Stationers which left him convinced that the cryptic inscription on the 90-foot stone had been completely worn away resultant of its employment as a beating stone.

The Oak Island crew tasks Charles Barkhouse and Alex Lagina with accompanying Crowell and Hancock to the site of the old Halifax bookbindery in order to search for the 90-foot stone. Following the cessation of their meeting, these four men travel to Halifax and promptly locate the old building. Inside, they meet with Dr. Allan Marble, historian and former president of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, and building representative Joe Landry of Halifax’s Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. These two men lead Charles, Alex, Doug, and Kel to the building’s basement where, after exploring for some time, they discover the entrance to an underground military tunnel which had long since been boarded up.

After finding nothing else of interest in the basement, the men exit the building and congregate outside, where Dr. Marble informs them that a former member of the nearby Halifax Club headquarters told his son that he believed a particular stone set into the Club’s floor was, in fact, Oak Island’s 90-foot stone. The crew unanimously agrees that this lead is worth investigation, and so Dr. Marble leads the way to the Halifax Club building.

As the men approach the building, the narrator describes how the Halifax Club, which’s headquarters were built in 1862 by a famous Scottish-Canadian builder and stonemason named George Lang, was a male-only fraternity peopled by some of the city’s most prominent citizens.

Upon entering, the Oak Island crew learns that Halifax Club building is unfinished and under construction, and that the identity of the floor stone in question is a mystery. They meet with Ryan Burke and Zach Woodworth, members of the construction crew tasked with the building’s refinishing, who suggest that they look for the stone in the basement. A subsequent search of the basement reveals nothing of interest.

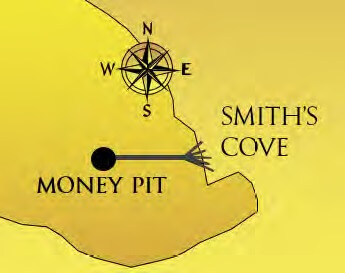

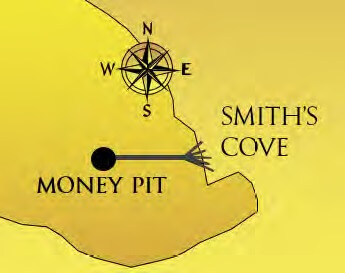

Back on Oak Island, Marty Lagina, Craig Tester, and Jack Begley, with help from metal detection and GPR experts Matt Savelle and Luke Malanson of Canadian Seabed Research Ltd., search for the infamous Smith’s Cove flood tunnel using ground penetrating radar technology. While the men work, the narrator recalls how men of the Truro Company, a 19th Century Oak Island treasure hunting syndicate, uncovered a set of five box drains under the beach at Smith’s Cove. These box drains- which were covered by layers of coconut fibre, eelgrass, and carefully-placed beach stones- converged like the fingers of a hand to form what they believed to be a single sloped flood tunnel- a boobytrap which fed seawater into the Money Pit.

The men conduct a ground penetrating radar scan of the Smith’s Cove area and discover a point at which they believe the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel might be located. The crew decides to excavate this point in the future.

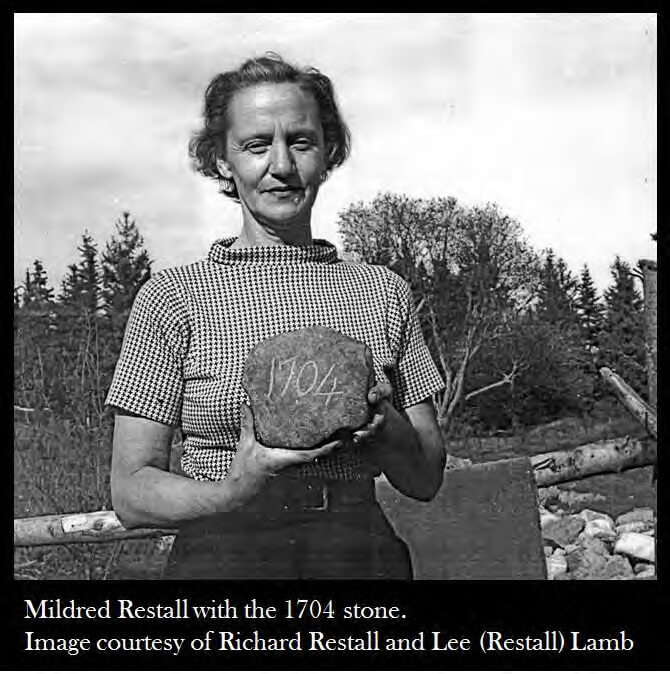

Later, Rick and Marty Lagina and Craig Tester, while working to clear logs from the Money Pit area, are visited by Dave Blankenship, Lee Lamb, and Lamb’s two children, Claire Bradfield and Brook Helland. Lee Lamb is the daughter and sister, respectively, of Oak Island treasure hunters Robert and Bobby Restall, who lost their lives in what is known as the Oak Island tragedy on August 17, 1965. Lamb, who appeared in Season 1, Episode 3 of The Curse of Oak Island, has returned to the island to show the Laginas and their crew the artifact known as the ‘1704 stone’. As Lee retrieves the item from her car, the narrator describes how the stone was accidentally discovered by Lee’s mother Mildred in 1960 while she, her husband Robert, and her sons Bobby and Richard were living on the island.

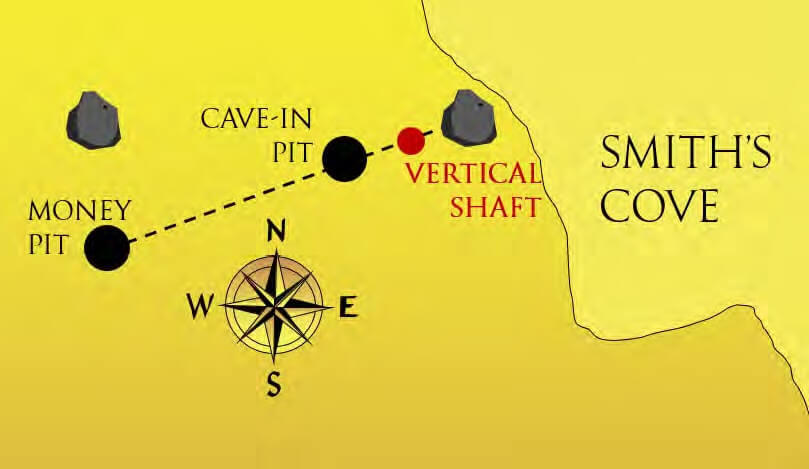

Lee and her children accompany Rick, Marty, Craig, and Dave to Smith’s Cove, where she points out the general location in which her mother discovered the 1704 stone. Lee mentions the ‘Vertical Shaft’, one of her father and brother’s most prominent discoveries on the island, and the fact that her brother Bobby documented its location on his own hand-drawn map of the island. Marty suggests that they use Bobby’s map to locate the Vertical Shaft, to which Lee replies “good luck with that.” The narrator then recounts how treasure hunter Robert Dunfield, who took over the Oak Island treasure hunt following Robert and Bobby Restall’s deaths, destroyed many of Oak Island’s landmarks, including the surface section of the Vertical Shaft, in a massive Money Pit-area excavation.

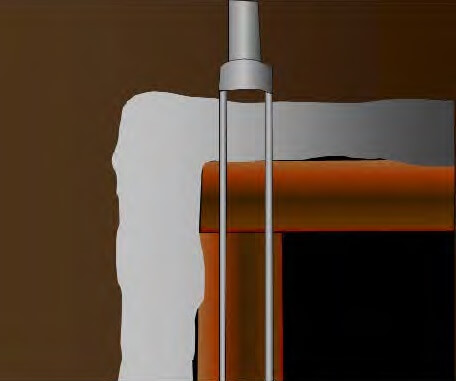

After Lee and her children conclude their visit to Oak Island, the Oak Island crew gathers at the Money Pit area. There, Vanessa Lucido of ROC Equipment explains how a newly-arrived piece of equipment, called an oscillator, will grind massive steel caissons into the Money Pit area. She asks that a member of the crew turn on the machine, and the crew unanimously nominates Dan Blankenship for the task. With the help of ROC Equipment operator Kent Peterson, the elderly veteran treasure hunter starts up the oscillator and the caisson begins its slow descent into the Money Pit.

Analysis

Valley 3

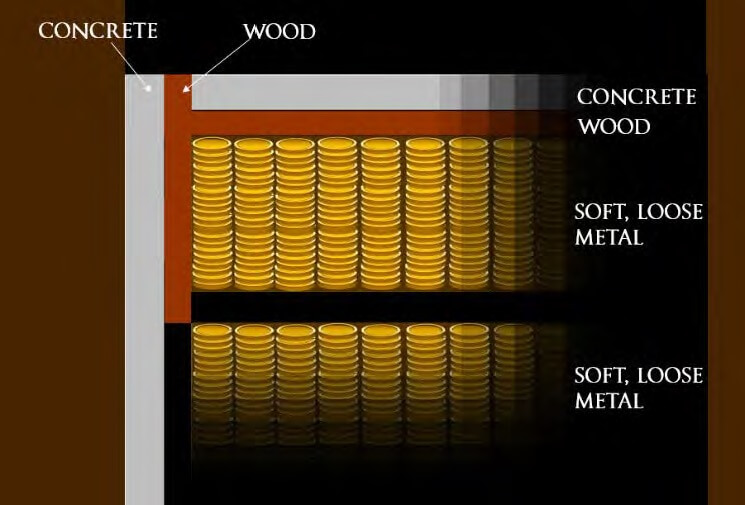

In the summer of 2015, Oak Island Tours Inc. under the direction of engineer Craig Tester brought up a 2-foot-long core sample from a hole drilled in the Money Pit area, which they named Valley 3. This sample, which came from a depth of 140’-142’, contained clay, old wood, and a material which could be either natural limestone or manmade concrete. The facts that the core sample contained a concrete-like substance followed by two pieces of wood- the first bearing horizontal-running grain and the second bearing vertical-running grain- led the Oak Island crew to speculate that they might have drilled into the side of the vault discovered by the Oak Island Treasure Company in 1897.

At first glance, one obvious problem with the Oak Island crew’s speculation is the fact that the Oak Island Treasure Company reported drilling through the top of the concrete-wooden vault at a depth of 153 feet, not 140-142 feet. The 11-foot gap between the bottom of the Oak Island Tourism Inc.’s core sample and the top of the Oak Island Treasure Company’s shaft is not insubstantial. However, when comparing these two depths, one must take into consideration the heavy-duty excavations of Robert Dunfield, which significantly altered the elevation of the surface of the Money Pit area. According to Kevin Burns, the executive producer of the History Channel’s The Curse of Oak Island, Dunfield’s operation resulted in the Money Pit’s surface being roughly 10 feet lower than when it was originally discovered by Daniel McGinnis, John Smith, and Anthony Vaughan in 1795. If true, this means that the Oak Island Tours Inc.’s core sample was taken from a depth of about 150-152 feet below the original Money Pit level- the approximate level at which Frederic Blair and William Chappell discovered the vault in 1897. Perhaps the Oak Island Tours Inc.’s core sample is a piece of the Chappell vault after all. In any case, the men of Oak Island Tours Inc. have taken to calling the vault the Tester Vault, in honour of its discoverer Craig Tester.

C1

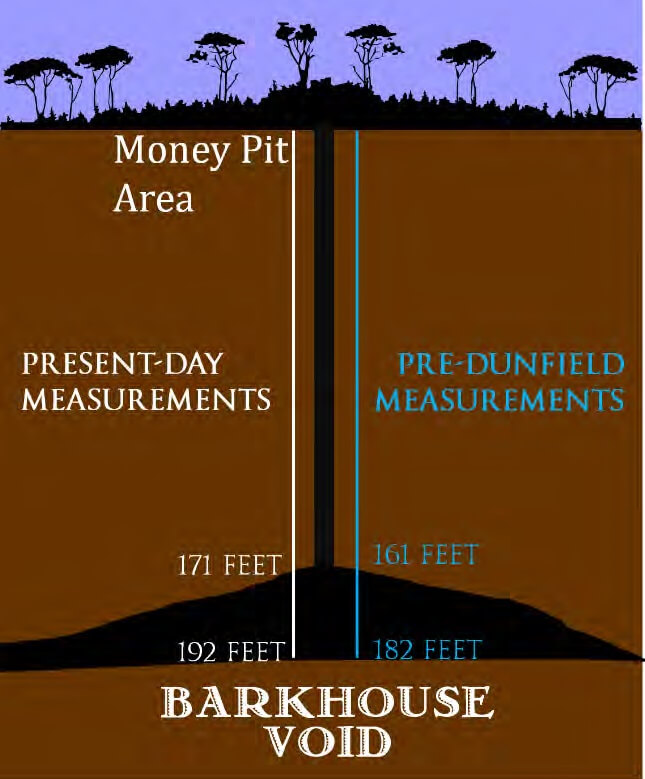

During his 25 years of Oak Island research, Oak Island historian Charles Barkhouse had come to the conclusion that the Money Pit was located at a spot just north of where the Oak Island crew drilled in Season 2, Episode 4 of The Curse of Oak Island. On Season 3, Episode, 12, the Oak Island crew drilled in the spot prescribed by Barkhouse- which they termed ‘C1’- and discovered some fragments of old oak wood at a depth of around 100 feet along with a 21-foot void beginning at the 171-foot depth. Since the entire Money Pit area is about 10 feet lower than it initially was following treasure hunter Robert Dunfield’s heavy duty excavations in the late 1960’s, this Barkhouse Void would have been located 161-182 feet below the pre-Dunfield surface. This finding is reminiscent of the Money Pit-area void discovered independently by treasure hunters George Green and Robert Dunfield, as well as a void discovered by former Oak Island treasure hunting syndicate Triton Alliance beneath a treasure shaft known as the Hedden Shaft.

In Season 3, Episode 13, a special camera was lowered down drill hole C1. Somewhere below the 171-foot depth, the camera picked up a shiny, gold-coloured object. The nature of this object has yet to be determined.

The 90-Foot Stone

In 1804, the Onslow Company, the current Oak Island treasure hunting syndicate, discovered a large, olive-coloured stone slab in the Money Pit at a depth of 90 feet. The stone- which measured 2.5 feet in length, 1.25 feet in width, and 10 inches in depth, and weighed about 175 pounds- is believed by some to be of either Swedish granite or porphyry, rocks not indigenous to Oak Island. Apparently, none of the Onslow Company members were able to make sense of the stone’s symbols or speculate as to their origin, although the company men unanimously interpreted the stone’s existence as a sign that the treasure they were seeking was close at hand. The Onslow Company workers laid the stone aside upon recovering it and retired for the day shortly afterwards. The following morning, the Money Pit was filled to 30 feet below the surface with water.

Many Oak Island researchers believe that Money Pit co-discoverer and Onslow Company shareholder John Smith took the 90-foot stone into his possession and had it built into the fireplace of his new Oak Island home in 1805, where he exhibited it to visitors to the island. In 1865, eight years after Smith’s death, the stone was removed from Smith’s fireplace and brought to Truro by Oak Island treasure hunter Jotham B. McCully. McCully kept the stone in his Truro home and showcased it to potential investors in his Oak Island treasure hunting scheme. Sometime after, the stone came into the possession of businessman A.O. Creighton, a hopeful Oak Island treasure hunter and partner in a Halifax bookbinding firm called A. & H. Creighton (or perhaps Creighton & Marshall Stationers). A.O. Creighton showcased the stone in the front window of his book bindery, hoping that it might attract investor interest in his Oak Island treasure hunting venture, the Oak Island Contract Company. When the Oak Island Contract Company failed to get off the ground, Creighton used the 90-foot stone as a base on which to beat individual sheets of paper. While the stone was employed for this purpose, the strange inscription on its face gradually wore away into obscurity. By the turn of the 20th Century, the inscription had faded completely. According to some unverified accounts, the stone was taken to Truro, Nova Scotia, in 1920, and was later returned to the bookbindery in Halifax in 1929. Then, sometime in the early 1930’s, the stone mysteriously disappeared, and has been missing ever since.

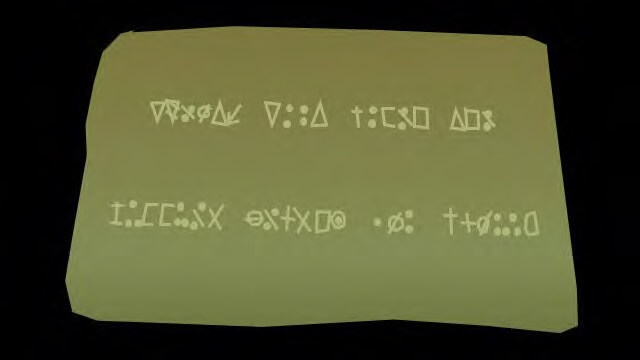

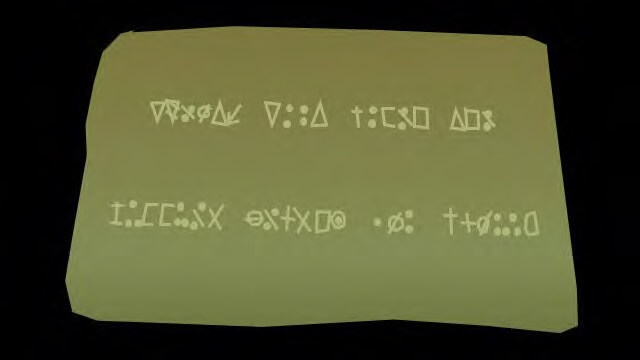

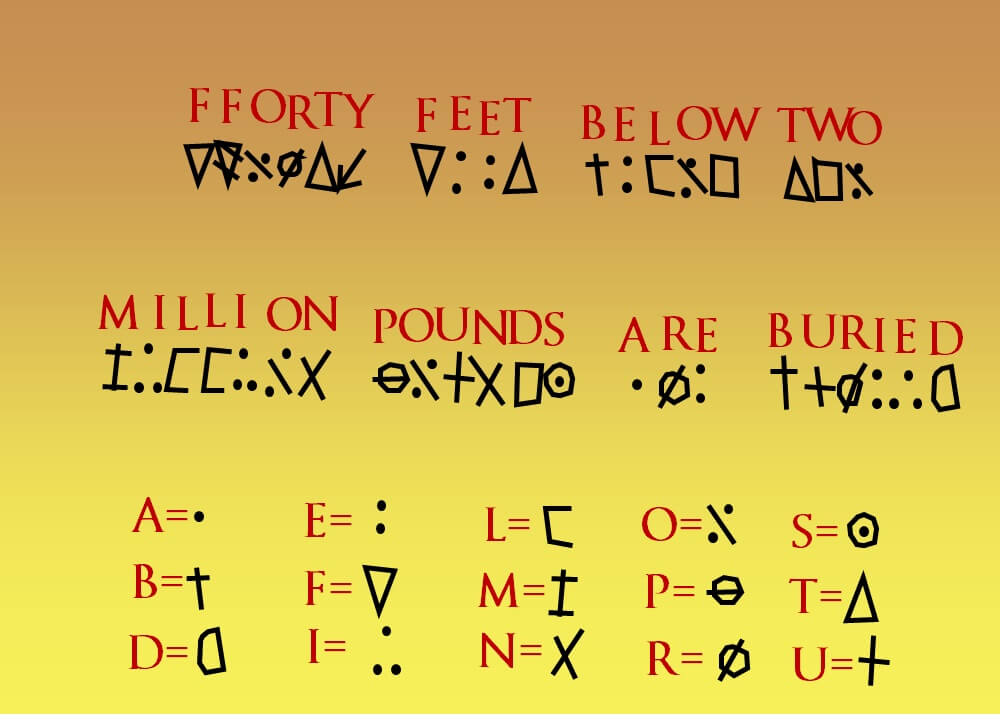

Shortly after the stone was taken from John Smith’s house and brought to Halifax in 1865, James Liechti, a linguistics professor from Halifax’s Dalhousie University, claimed that the stone was a cipher which, when decoded, read: “Forty feet below two million pounds are buried.” Although no rubbings were made of the stone’s inscription, some believe that the cryptic markings may have been copied down at some point. The only supposed copy of the inscription on the 90-foot stone surfaced in April 1949, in a letter written by Nova Scotian Reverend A.T. Kempton

to Oak Island treasure hunter Frederick Blair. Kempton, in his letter, maintained that he received a copy of the stone

inscription from an “old Irish School Master” who resided somewhere in Mahone Bay. That same year, the Kempton symbols found their way into Edward Rowe Snow’s book True Tales of Buried Treasure. The Kempton symbols form a simple substitution cypher which, when decoded, read the same message allegedly decrypted by Dalhousie Professor James Liechti in 1865: “Forty feet below two million pounds are buried.” It should be mentioned that many serious Oak Island researchers doubt the authenticity of the Kempton symbols, believing the substitution cipher they suggest to be too simplistic. IBM cryptoanalyst Stephen M. Matyas, upon analyzing the Kempton symbols, concluded they were “most likely a fraud” and “cannot be trusted.”

In 1971, Dr. Ross Wilhelm, a Michigan professor who worked as a code breaker during World War II, bolstered the plausibility of the veracity of the Kempton symbols by claiming they formed a double cipher which could be decrypted using a cipher wheel. More recently, Wilhelm’s theory has been supported and supplemented by cryptographer and Oak Island researcher Daniel Ronnstam.

In 1980, Barry Fell, a Harvard zoology professor and marine biologist with a passion for ancient languages, published his book Saga America, a sequel to his book America BC (1976), in which he proposed that ancient Old World peoples regularly made voyages to the New World long before Christopher Columbus’ 1492 discovery. In one small section of Saga America, Fell mentions that the Kempton symbols, allegedly inscribed on Oak Island’s 90-foot stone, actually spelled a Libyan Arabic message using a late Tifinagh script. This message, when translated, read, “To escape contagion of plague and winter hardships, he is to pray for an end or mitigation, the Arif: the people will perish in misery if they forget the Lord, alas.”

Harry Bowdoin

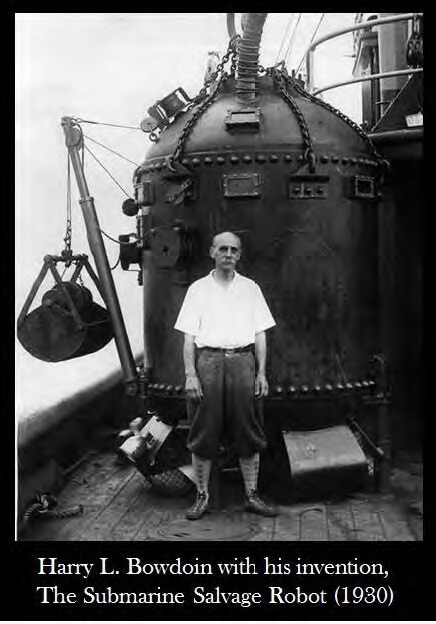

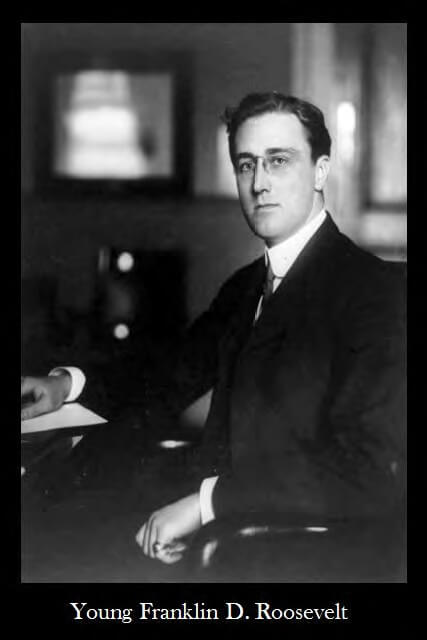

In 1909, a treasure hunter named Captain Harry (or perhaps Henry) L. Bowdoin decided to take a stab at solving the Oak Island mystery. Bowdoin was an American inventor, ex-diver, and marine engineer who was fascinated with the prospect of recovering lost underwater treasure. He claimed that “with modern methods and machinery, the recovery of the [Oak Island] treasure is easy, ridiculously easy.” In 1909, he made a contract with Frederick Blair (Oak Island’s landowner at the time) which allowed him to treasure hunt on Oak Island for a year, and promptly formed the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company. Interestingly, one of the company’s shareholders was a young New York law clerk named Franklin Delano Roosevelt- a man who would later go on to serve as the 32nd President of the United States.

Once Bowdoin had sold enough shares to become operational, he and his crew set up shop on Oak Island. He dubbed the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company’s island headquarters “Camp Kidd,” in reference to the theory that the Money Pit treasure is the long-lost treasure of pirate William Kidd- a theory to which he subscribed. Immediately, Bowdoin and his crew, through the use of divers, got to work searching for the Smith’s Cove box drains. When they were unable to find them, they sent a diver down the flooded Money Pit and learned that it was clear to a depth of 113 feet. Instead of draining the Pit, Bowdoin, who had not raised as much money for his venture as he had initially anticipated, decided to conduct an exploration drilling operation in the Money Pit. He reasoned that if he produced concrete evidence of the vault believed to lie in the Pit at a depth of 161 feet, he would have an easier time attracting investor interest.

Unfortunately for Bowdoin, the drilling results revealed precious little. Aside from blue clay between the 130-146-foot depths and 6-10-inch-thick layers of cement from 146-149 feet, the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company brought up no evidence of treasure or man-made structures from the Money Pit. These findings, or lack thereof, thoroughly discouraged investors, who quickly withdrew their support. Unable to raise the capital they needed to carry out additional exploration and excavation, the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company folded.

Following his ill-fated stint on Oak Island, at the end of which he and island landowner Frederick Blair had a falling out, Bowdoin wrote a bitter summary of his Oak Island experience in which he ultimately stated his belief that there is not, in fact, any treasure on the island to find. In his article, which was published in a Nova Scotian newspaper, Bowdoin asserted that he had travelled to Creighton & Marshall Stationers in Halifax to examine the 90-foot stone, and found it to be completely devoid of markings of any kind. Some Oak Island researchers believe that Bowdoin’s assertion indicates that the inscription on the 90 foot stone wore away as a result of its being employed as a beating stone, was deliberately defaced at some point, or never existed in the first place. Others suggest that the stone, in actuality, still did bear an inscription at the time Bowdoin wrote his article, and that Bowdoin lied about its condition in order to spite Frederick Blair, with whom his relationship was strained.

It is somewhat ironic that the main character of what is probably the most boring chapter of Oak Island history has one of the most interesting backstories. As mentioned earlier, Captain Harry (or perhaps Henry) L. Bowdoin was an inventor, ex-diver, and marine engineer who was obsessed with recovering lost underwater treasure. A number of

old articles have been written about the arrogant engineer’s many achievements, all of which assign Bowdoin a different hometown. Some claim he was a resident of Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Others maintain he was a New Yorker who lived in Manhattan or Whitestone, Queens. Others still assert that he was a native of Bayonne, New Jersey. All, however, agree that he was an American citizen.

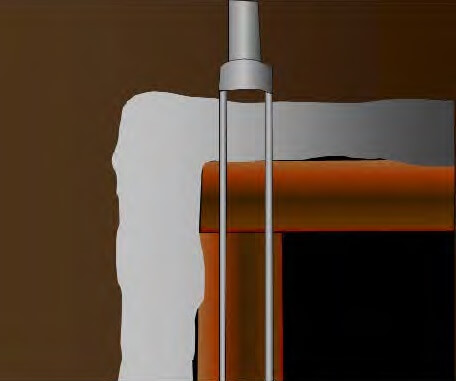

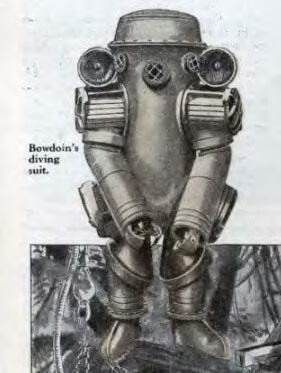

Before his death in 1935, Bowdoin invented a number of fascinating underwater treasure-hunting apparatuses. Before arriving on Oak Island in 1909, he had invented what he called the “Bowdoin Air Lock Caisson,” a subaqueous treasure-retrieval device which used positive air pressure to keep water out. In 1915, six years after leaving Oak Island, he invented a type of heavily-armoured atmospheric diving unit (a submarine suit designed for ultra-deep-water dives) with oil-filled rotary joints. And in 1930, he invented a type of controllable diving bell, a submarine

Before his death in 1935, Bowdoin invented a number of fascinating underwater treasure-hunting apparatuses. Before arriving on Oak Island in 1909, he had invented what he called the “Bowdoin Air Lock Caisson,” a subaqueous treasure-retrieval device which used positive air pressure to keep water out. In 1915, six years after leaving Oak Island, he invented a type of heavily-armoured atmospheric diving unit (a submarine suit designed for ultra-deep-water dives) with oil-filled rotary joints. And in 1930, he invented a type of controllable diving bell, a submarine

chamber which enabled occupants to do salvage work on the ocean floor. Bowdoin also invented a number of non-treasure- hunting-related devices, including a “Theatrical Apparatus”- designed “for use in giving exhibitions or performances whereby in connection with a tank of water, drowning, disappearing, rescuing and other scenes may be affected…” – a rudder lock for boats, and an ice cream cone-making machine.

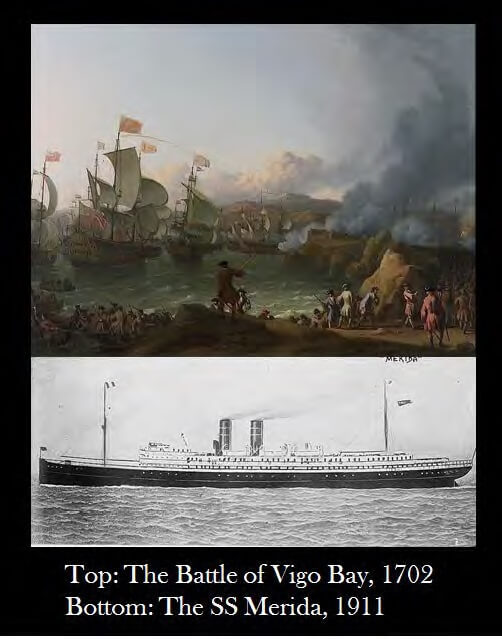

Although Bowdoin’s brief and ill-fated stint on Oak Island was his first treasure-hunting adventure, it was not his last. In 1916, Bowdoin tested his new atmospheric diving unit in a failed attempt to retrieve the $120,000,000 Spanish treasure believed to lie at the bottom of Vigo Bay where, in a 1702 naval battle of the War of Spanish Succession, seventeen Spanish treasure galleons were sunk by English and Dutch warships. Years later, in 1932 and 1933, Bowdoin attempted to salvage the $2,000,000 treasure of the sunken SS Merida- an American steamer loaded with Yucatan aristocrats (and the contents of their safes) fleeing the Mexican Revolution- which sank off the Virginia Capes at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay in 1911.

The Smith’s Cove Flood Tunnel

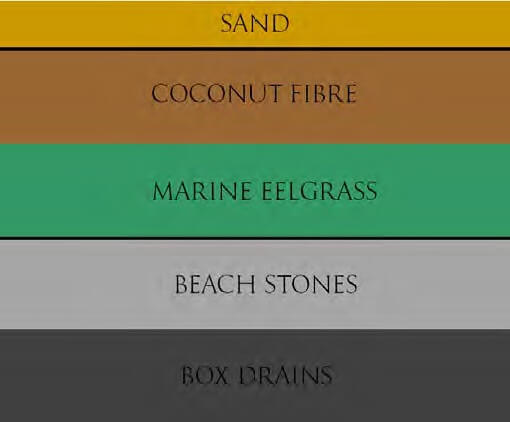

In the summer of 1850, a member of the Truro Company noticed that seawater trickled as if from underground at several places on Smith’s Cove during low tide. In the words of one of the Truro Company members, the beach “gulched forth water like a sponge being squeezed.” Upon further investigation, the Company learned, to their astonishment, that a large part of Smith’s Cove was actually a huge artificial filter designed to prevent box drains below from being clogged with debris.

This massive filter, about 145 square feet in area, was composed of several different layers of material. Below the layer of sand which covered its surface was a 2-inch-thick layer of coir, or coconut fibre. According to one account, the coir was topped with a thin layer of blue clay. Below the coconut fibre was a 4-inch-thick layer of decayed marine eelgrass. Below the eelgrass was a layer of flat, clean beach stones. And below the beach stones was a series of carefully-constructed box drains which apparently converged, like the folds of a hand fan, to a point somewhere along the Cove’s shore. The drains- which, according to some accounts, were eight inches wide- were graded so that they sloped downwards towards the shore.

The Truro Company members believed that the drains fed a flood tunnel which extended from Smith’s Cove to the Money Pit. This flood tunnel, they believed, was the reason the water level in the Money Pit could not be lowered via bailing. Accordingly, they built a cofferdam around Smith’s Cove so as to give them better access to the beach workings before systematically dismantling the box drains, working from the cofferdam towards the shore. Before the Truro Company was able to reach the point at which the drains apparently converged, however, the cofferdam was destroyed by the implacable Atlantic elements and the deconstruction project was abandoned.

The Restall Family

In October 1959, Mel Chappell, Oak Island’s landowner and Treasure Trove licence holder at the time, signed a contract with Robert Restall, a hopeful Oak Island treasure hunter who had been writing him persistently since 1955.

Restall- a plumber, steamfitter, tinkerer, and ex-motorcycle stunt rider from Hamilton, Ontario- was not a wealthy man. However, the financial support he received from his friend Fred Sparham, coupled with his keen analytical mind, his strong mechanical inclination, his honest character, and most of all his indomitable perseverance (as

evidenced by the many letters he wrote to Chappell from 1955- 1959), made him, in Chappell’s mind, the perfect man for the job. That month, Restall, along with his wife Mildred and his eighteen-year-old son Bobby, moved into a tiny tool shack on Oak Island near the Money Pit. Grateful for the rare and long-sought-after opportunity to search for Oak Island’s famous treasure, and eager to please the ever-restless Chappell, Robert and his son got to work preparing for a grueling winter excavation of Smith’s Cove.

Below is a video of Robert and Mildred Restall performing in the so-called ‘Globe of Death’. Before coming to Oak Island, Robert and Mildred worked seasonally as motorcycle stuntsmen. Video courtesy of Lee Lamb.

Throughout the fall of 1959 and the winter of 1959/60, Robert and Bobby Restall dug a number of test holes along the Smith’s Cove beach in search of the legendary flood tunnel that had thwarted Oak Island treasure hunters time and time again since 1804, when the Onslow Company first reached the Money Pit’s 90-foot level. Loath to destroy potential archaeological evidence left behind by the mysterious men responsible for the original Oak Island workings, the father and son eschewed the use of heavy machinery, opting instead to labour with pick and shovel as their Oak Island predecessors had done. While digging in Smith’s Cove, they uncovered the remains of the massive coir-eelgrass-stone filter first discovered by the Truro Company in the summer of 1850, and learned that it was far larger than previously believed.

Robert and Bobby Restall toiled on Smith’s Cove for several years, making a number of intriguing discoveries. They remained on Oak island until their untimely deaths in 1965.

Lee Lamb

Lee Lamb is Robert and Mildred Restall’s first child and only daughter. Although she spent relatively little time on Oak Island compared to her parents and brothers, her accounts of the Restall treasure hunt, which she details in her books Oak Island Obsession: The Restall Story (2006) and Oak Island Family: The Restall Hunt for Buried Treasure (2014), are nevertheless the best sources on this particular chapter of Oak Island history.

In Oak Island Obsession: The Restall Story, Lamb begins with a detailed backstory of Robert and Mildred. She goes on to describe her own childhood, and recounts anecdotes from her early life in Hamilton, Ontario, which illustrate her family members’ unique characters and personalities. Lamb describes her father’s struggle to secure digging rights on Oak Island and includes a number of the letters written between him and Mel Chappell. She includes some of her mother Mildred’s insightful accounts of Oak Island life, as well as a few stories written by her brother Ricky. She chronicles her family’s Oak Island treasure hunt by seamlessly weaving her own narrative with her father’s many letters to friend and investor Fred Sparham, and by including samples of Bobby Restall’s many journal entries, sketches and articles.

Oak Island Family: The Restall Hunt for Buried Treasure is a shorter summary of Oak Island Obsession specifically written for teenagers and young adults.

More recently, Lee Lamb has published Strange Legacy: A Memoir of Paranormal Events (2016), a brief autobiography in which she describes a number of her own strange experiences which she attributes to the supernatural. Some of these experiences include an out-of-body/ near-death experience, premonitions, episodes of clairvoyance, and other strange phenomena.

In October 2016, Lamb published another autobiography, A Kid on the Carnival: The Glory Days, in which she recounts her childhood experience of touring with the Conklin carnival.

The Oak Island Tragedy

Tuesday, August 17, 1965, began as just another day on Oak Island for the Restall family. In the early afternoon, Robert Restall peered into a flooded shaft to make sure that the pump was running smoothly (at that time, he and his son Bobby were sinking shafts along the hypothetical line of the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel, hoping that they might intercept the legendary booby trap and stem its water flow). Suddenly, he fell in. Robert Restall had gotten a whiff of some sort of toxic gas which filled the pit below. Some Oak Island researchers theorize that it was carbon monoxide, exhaust from the gas-powered pump which was running at the shaft’s bottom. Others maintain that it might have been methane, or swamp gas, a product of rotten underground vegetation. However, the facts that witnesses described the gas as having a pungent smell akin to the stench of rotten eggs, and that Robert Restall succumbed to the gas almost instantly, indicate that the gas was almost certainly hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a powerful, deadly gas sometimes encountered by oil drillers and underground miners.

Upon seeing his father topple into the pit, Bobby, who was gathering brush at the time, rushed to his

aid. He had barely begun to descend the shaft’s ladder when he, too, fell in. Karl Graeser, who had also rushed to help, similarly fell to the bottom of the shaft, along with Cyril Hiltz and Andrew Demont, two young cousins who worked as labourers on the Restall crew, and a worker named Leonard Kaizer. According to Andrew Demont in a later account, the last thing he remembered before passing out was a lucid Bobby Restall holding his father’s head above water.

Among the handful of tourists on Oak Island at the time was a firefighter from Buffalo, New York, named Edward White. White was certain that the six men had fallen victim to some sort of toxic gas. Despite the protests from his wife, he tied a handkerchief around his mouth and nose, secured a rope around himself, and asked a fellow bystander to lower him into the pit.

The handkerchief around White’s mouth and nose did little to protect him from the gas. In spite of this, the Buffalo native managed to rescue two men- Kaizer and young Demont- from the shaft before admitting that he could not take the gas any longer. By this time, the water in the shaft was rising fast; the pump was no longer working.

Tragically, Robert and 24-year-old Bobby Restall, Karl Graeser, and 16-year-old Cyril Hiltz drowned to death in that pit, bringing the Oak Island death toll up to 6. Although most attributed the tragedy to bad luck, some of the more superstitious locals suggested that the four men had fallen victim to a curse put on the island by the original builders. In time, this belief gave rise to what is now a popular Oak Island legend: that a total of 7 people must die before Oak Island will reveal its secrets.

1704 Stone

On November 6, 1960, Robert’s wife Mildred made an intriguing discovery which may shed some light on the mysterious origins of the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel. To give the story of this discovery some context, it should be noted that, starting in the fall of 1960, Mildred enrolled Ricky in a Government of Nova Scotia correspondence

course so that he could continue his education while living on Oak Island. In the mornings, she would help Ricky with his lessons and homework. In the afternoons, if the weather permitted, she would often accompany Ricky as he explored various parts of the island. On the afternoon of November 6, 1960, Ricky was spending his post-lesson time playing with fish in a tide-pool on Smith’s Cove not too far from where Robert and Bobby were working. Nearby

the tide pool farther down the beach was a dump pile at which, earlier that season, the two men had shoveled the rubble from one of their Smith’s Cove shafts. The pile’s dirt and debris washed away with the tide, leaving behind nothing but the rocks. While Ricky played in the pool, Mildred idly examined some of the stones in the pile. To her surprise, she gradually realized that one of the stones appeared to have some characters carved onto its surface… but she wasn’t sure. Curious, she retrieved the stone, washed it off, and sent Ricky to inform Robert and Bobby that she might have found something significant.

At first, the men were irritated at having been interrupted from their work. However, when they saw what Mildred had discovered, they immediately examined the rest of the rocks in the dump pile to see if there were any more like it. As it turned out, the rock Mildred had recovered was the only stone bearing an inscription.

In the beginning, the inscription on the stone was dark and hard to make out, although it had obviously been carved with some sort of chisel. As time drew on and the stone dried out, however, the writing on its surface became clearly legible. The stone read ‘1704’ in a style which, according to experts, was common in England around the turn of the 18th Century.

The Vertical Shaft

In the summer of 1961, Robert and Bobby Restall discovered what they described as a carefully-constructed

stone dome hidden among the rocks of Smith’s Cove at a location in line with the Money Pit area, an Oak Island landmark known as the Cave-in Pit, and two drilled rocks discovered on the island. Beneath the dome was a shaft about 1.5 feet in diameter which disappeared deep into the earth. When tested, it appeared that the hole led to some underground water. They called this shaft the Vertical Shaft.

The Restalls believed that the Vertical Shaft not only led to the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel, but was also the spot at which the original Oak Island builders meant for the flood tunnel to be shut off. Robert Restall theorized that the original builders might have designed the shaft so that the Smith’s Cove flood tunnel would shut off once it was stuffed with a ship’s sail and packed with clay. Accordingly, he tried to pump cement down the Vertical Shaft so that it might similarly shut off the flood tunnel. Unfortunately, the cement Restall purchased from Western Shore was of inferior quality, and did not make a good seal; the cement was washed away with the tide.

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookstore:

Leave a Reply