The Curse of Oak Island: Season 10, Episode 2 Explained

Borehole DN12.5

Season 10, Episode 2 of The Curse of Oak Island begins at the Money Pit area, where geologist Terry Matheson and historian Paul Troutman are overseeing the drilling of Borehole DN12.5 – an operation which commenced near the end of the previous episode. The treasure hunters are joined by Rick Lagina, Craig Tester, and Scott Barlow, who are present when a core sample taken from a depth of 98 feet is sliced open. This sample contains a fragment of wood below what appears to be in situ soil. The treasure hunters speculate that they may have drilled into the tunnel discovered the previous episode via Boreholes K15.5 and M16.25. The narrator remarks that this new wood sample is located five feet higher than the other wood samples recovered from the abovementioned boreholes – an indication that the tunnel is slightly graded. The treasure hunters agree that they ought to test the water in DN12.5 for traces of gold, which was found in other Money Pit water samples the previous year.

The Lot 7 Jewel

Later on, Gary Drayton and Jack Begley go metal detecting on Oak Island’s Lot 7, on which they found a musket ball and a bronze coin in the previous episode. They uncover a small, heavily corroded object which Drayton tentatively identifies as a cloak pin inset with some sort of jewel. Begley suggests that this find evokes the rhodolite garnet brooch found on adjacent Lot 8 in Season 5, Episode 16. The narrator then reminds us of the theory proposed by researcher Scott Clarke in Season 9, Episode 21, that the garnet is actually one of the twelve gemstones from a Freemasonic Royal Arch High Priest breastplate, noting that several prominent people involved in the Oak Island treasure hunt – namely Reginald Harris, the lawyer of treasure hunters Frederick Blair and Gilbert Hedden; Oak Island treasure hunter and landowner Mel Chappell; and Luther Archibald, the cousin of Oak Island treasure hunter Adams Archibald Tupper, were all Grand High Priests in the Freemasonic Grand Chapter of Nova Scotia.

In a later scene, Drayton and Begley show the artifact to Rick Lagina and Laird Niven in the Oak Island Interpretive Centre. Niven opines that the pin is a piece of decorative jewelry and examines it under a microscope. The gem which dominates the pieces proves to be of a dark blue hue. The archaeologist refuses to date the artifact, and suggests that they clean it and subject it to a CT scan.

Royston Cave

As hinted in the title of the episode, ‘Across the Pond,’ most of Season 10, Episode 2 takes place in England, across the Atlantic from Oak Island. Near the beginning of the episode, Marty Lagina, Alex Lagina, and Charles Barkhouse travel to the town of Royston, England, to meet Gretchen Cornwall, author of the 2018 book The Secret Dossier of a Knight Templar of the Sangreal and the 2022 book Oak Island’s Mysteries of the Map, House of Rochefoucauld: The Templar Statue and Royston Cave, with whom they had a video conference at the end of the previous episode. Cornwall takes the treasure hunters to Royston Cave, a mysterious artificial cave beneath the town which some researchers believe was once used as a secret meeting place by members of the Knights Templar. As the party enters an underground tunnel which leads to the cave, the narrator explains that the structure was re-discovered in 1742, “when a secret entrance was discovered during construction in the town’s marketplace.”

The Cave’s official website, RoystonCave.co.uk, states that the tunnel was constructed after the Cave’s discovery “to allow easier access for visitors”. It also elaborates on the structure’s 1742 discovery in a paragraph which reads:

“Royston cave was discovered by accident in 1742 by workmen erecting a bench in the butter market above. A millstone was found in the ground which, when lifted, uncovered a vertical well-like shaft. Toeholds had been cut into the chalk to form steps. A small boy was volunteered to make the first descent and found the cave to be filled with earth and debris.

“In the expectation of finding treasure, the shaft was enlarged and the cave was emptied, uncovering extensive carvings in the lower part of the chamber. No scientific archaeological investigation was made at the time but according to [Reverend George] North, who visited the cave shortly after its discovery, the contents included a skull, some decayed bones, fragments of a small drinking vessel and an unmarked piece of brass.”

In his 1884 book, The Origin and Use of the Royston Cave, English historian Joseph Beldam mentions other artifacts which were unearthed during the cave’s 1742 excavation, some of which are especially interesting considering the parallels drawn in this episode between Royston Cave and the Oak Island Money Pit. In addition to red bricks of ancient manufacture, the 18th Century amateur archaeologists who opened the cave unearthed very thick fragments of oak, iron components of a chest, a large lump of charcoal powdered with sulfur, and a huge quantity of animal bones. At the very bottom of the cave was a human grave. Recall that human bones, animal bones, charcoal, old iron, pottery fragments, and large pieces of oak have all been recovered at depth in the Money Pit area.

Royston Cave itself proves to be a bell-shaped chamber measuring eight metres (26 feet) in height and five metres (16 feet) in diameter. The lower portion of its walls is covered with carvings depicting Christian symbols, mysterious symbols, medieval arms and armour, and what appear to be soldiers, knights, and members of the nobility.

The Cave’s official website identifies four of the carved figures as Christian saints, namely St. Christopher, the patron saint of travellers; St. Catherine of Alexandria, who is depicted alongside the breaking wheel upon which the Roman Emperor Maxentius ordered her execution in 305 A.D.; St. Lawrence, who is depicted holding the gridiron on which he was martyred; and a depiction of a holy knight whom some have interpreted as St. George. Other carvings are believed to depict Christ and His twelve apostles; English King Richard the Lionheart; and King David I of Israel, whom some believe is actually Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. In addition to the Christian carvings, Royston Cave contains several pagan graffitos, including a depiction of a Celtic fertility goddess; and a strange image of a man holding a candle and a skull.

In his book, Joseph Beldam put forth a tentative argument that the cave was first dug by Celtic Britons for the purpose of Druidic worship; used as a sepulcher by foreign legionaries during the Roman occupation; employed as a chapel by veterans of the Crusades who admired its resemblance to ancient Christian chapels in the Holy Land; and finally sealed during the 16th Century English Reformation.

In the show, Gretchen Cornwall explains that some theorists believe the cave was used by the Knights Templar as a secret initiation chamber, and that she herself believes that its entrance was concealed by a market stall on the street above. When Alex Lagina asks Cornwall for the dimensions of the cave, the writer states: “It’s approximately 16 feet, but as we get into the centre- the centre circle- it’s more like 13 feet.” The “centre circle” to which Cornwall referred is probably an octagonal stone podium located in the centre of the cave, on which she and the treasure hunters are standing. Marty remarks that the podium’s 13-foot diameter evokes the original Money Pit found in 1795, which was also said to have a diameter of 13 feet. Alex then reminds his fellow treasure hunters of the 13-foot diameter of the Initiation Wells of Quinta de Regaleira – a quinta, or manor house, in the town of Sintra, Portugal, which once served as a Templar stronghold, which the team examined the previous year. Similar to Royston Cave, some theorists suspect that the Initiation Wells were used by the Knights Templar as initiation chambers.

Marty asks Cornwall whether there are any other potential connections between Royston Cave and Oak Island. In response, the author directs the treasure hunters’ attention to a large crucifix carved into the cave’s wall and suggests that its shape evokes that of the mysterious lead cross found on Smith’s Cove back in Season 5, Episode 10. Recall that, immediately after unearthing the artifact with Gary Drayton, Rick Lagina noticed that the lead cross’s peculiar lopsided shape was similar to that of the Domme Cross, a graffito carved into the walls of a prison in Domme, France, in which Templar knights were imprisoned following their mass arrest on October 13th, 1307. A laser ablation test conducted in Season 6, Episode 6 revealed that the lead of which the cross is composed derives from a medieval mine in southern France, further supporting the implicit theory, apparently espoused by several members of the Oak Island team, that the cross is a Templar artifact.

Marty concedes that the Royston Cave crucifix does indeed resemble the lead cross. “Dimensionally,” he says, “that is basically the same thing. The head is off to the side. Even one arm of the cross is shorter than the other, too.”

The 1347 Carving

Cornwall then points out a ring of bricks encircling the upper lip of the cave, one of which bears the carved inscription “1347”. She remarks that the date 1347 also appears on a mysterious map of Oak Island furnished by the late New York-based researcher Zena Halpern back in Season 4, Episode 1. Beside the date are two French words which translate to ‘The Landing’.

The date 1347 does not accord with Halpern’s own theory that English Templar knight Sir Ralph de Sudeley made a voyage to the New World, specifically to what is now the state of New York, in 1179, and that Scottish earl Henry Sinclair, being in possession of the Templars’ legendary treasures, deposited them on Oak Island in 1397. Although she offered no explanation for the 1347 date during any of her appearances on The Curse of Oak Island, Halpern did expound on it in her 2017 book The Templar Mission to Oak Island and Beyond, concocting a theory to explain it which conflicts with her own theory that Henry Sinclair brought Templar treasures to Oak Island in 1397. On the subject of the 1347 map, she wrote:

“The 1347 date obviously is after the 1179-80 Templar voyage [of Ralph de Sudeley]. Is the date 1347 significant? Researcher Doug Crowell found a compelling answer. The cornerstone in the famous Royston Cave, a Templar repository in Hertfordshire, England, has the 1347 date carved into it. The bell-shaped artificial cave was cut out of the chalk bedrock and used as a secret hideout and repository by the outlawed Templars.

“According to many historians, the Templars occupied Royston Cave from 1307 (when they were outlawed) to 1347, during which time they carved hundreds of images on the walls of the cave. I believe that in 1347, when the Bubonic plague swept cross England, the Templars planned their escape. They knew about Oak Island from Ralph de Sudeley’s 12th Century visit, gathered their treasures, and set sail, landing on Frog Island,” Frog Island being a small isle located a short distance from Oak Island.

Back in Royston Cave, Marty and Alex Lagina speculate that, if Zena Halpern’s 1347 map is legitimate, and that the date on the map denoted a 1347 Templar voyage to the New World, the 1347 inscription in Royston Cave would probably have been carved in commemoration of that event. Pointing to the carving, Marty says, echoing Zena’s theory, “The conjecture would be that’s a commemorative stone. It says, ‘Alright guys, we’re leaving this place now. It’s become too dangerous. They inscribe it, because people do that, and it actually is kind of like a cornerstone, where you put such things, and then they pack up and go. According to you,” he says, looking at Gretchen Cornwall, “to Oak Island.”

The Legend of Melusine

Cornwall then points out a third carving on the wall depicting an armless anthropomorphic torso wearing a crown and what appears to be either a dress or a tunic. She states that she believes the lower end of the garment is actually a fish-like tail, and suggests that the figure is a depiction of Melusine, the legendary nymph-like ancestor of the noble French Houses of Plantagenet, Lusignan, and, by extension, La Rochefoucauld.

According to medieval European legend, Melusine was one of the three triplet daughters of a Scottish king named Helmas and a beautiful fairy called Presine. At Presine’s insistence, Helmas swore a vow to never look in on her during childbirth, or while she lay in child-bed. When Helmas broke this vow, Presine fled with her daughters to the Isle of Avalon, a legendary island which features prominently in the Arthurian Romances.

When her daughters were fifteen years old, Presine told them of the promise their father had broken. Eager to avenge their mother, the sisters imprisoned King Helmas in a cave carved inside a mountain in Avalon, along with all his possessions. When he died, Presine buried her husband in the mountain prison and tasked a giant with guarding his tomb against intruders.

Despite his betrayal, Presine still loved her husband, and was angered by her daughters’ mistreatment of him. As punishment, she cursed each of them with a unique affliction. Melusine’s curse was to transform into a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. Whomever she married must not approach her in her altered state, lest he lose his lands and good fortune.

Melusine went on to marry a French knight named Raymond, the ward of the earl of Poitiers, who met her during a hunting trip in the Coulombiers Forest during which he accidentally slayed his lord while attempting to defend him from a wild boar. She made her husband swear to never ask where she went on Saturdays, assuring him that there was no sinister reason for her mysterious absences on the Sabbath. Melusine and Raymond went on to have ten children, each of them bearing some deformity, and for years Raymond faithfully kept his promise to never inquire into his wife’s mysterious Saturday disappearances.

One Saturday, on the advice of his brother, who had heard rumours that Melusine was routinely unfaithful to her husband on that day of the week, Raymond spied on his wife while she was bathing saw her in her half-serpent form. Horrified yet deeply repentant, Raymond decided to keep his transgression a secret, unaware that Melusine knew of his offense and had forgiven him for it on account of his remorse.

Years later, one of Melusine and Raymond’s sons, Geoffrey, discovered his brother, Fromont, had become a monk. Enraged by Fromont’s decision to abandon a life of chivalry for one of prayer and contemplation, and convinced that it was influenced by some sort of enchantment the monks exercised over him, Geoffrey set fire to the abbey in which his brother was living, killing Fromont and all the monks who lived there.

When Raymond learned of his son’s fratricide, he attributed Geoffrey’s crime to wickedness he inherited from his accursed mother, and called Melusine a serpent in front of his retainers. With a hideous shriek, Melusine transformed into a huge snake and flew out the castle window, never to return.

According to medieval European legend, many French royal houses, including the House of La Rochefoucauld, are descended from Melusine and Raymond. In the show, the narrator reminds us that the name Francois de La Rochefoucauld is scrawled into the margins of Zena Halpern’s 1347 map of Oak Island. He then reiterates the theory that the Oak Island treasure was deposited by French navy men during the Duc d’Anville Expedition of 1746, which was introduced back in Season 5, Episode 10.

Capture Document of the Lively

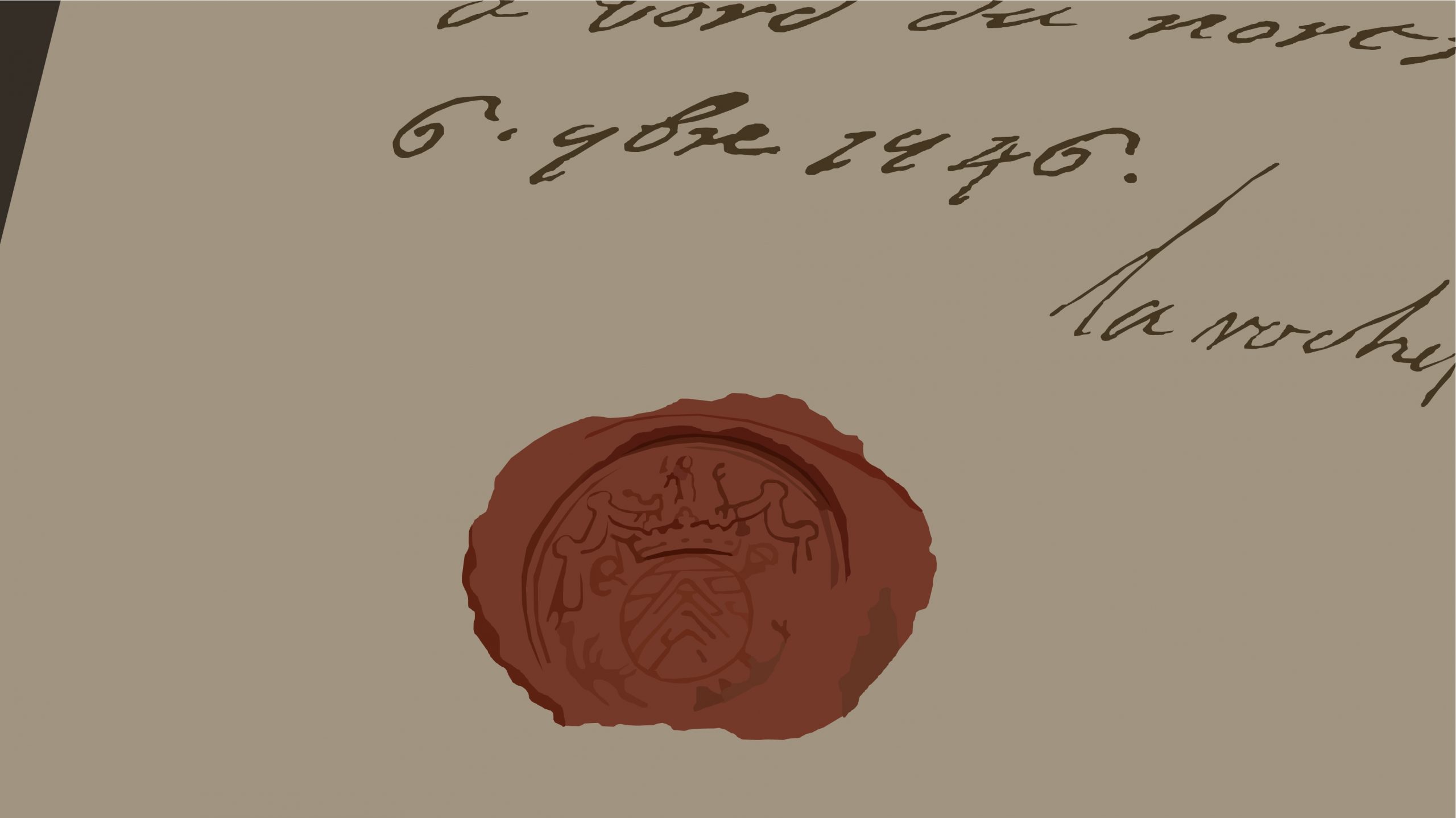

Later in the episode, Marty Lagina, Alex Lagina, and Charles Barkhouse meet with historian Paul Stewart at the United Kingdom’s National Archives in London, England. Stewart shows the treasure hunters an old paper documenting the capture of a British ship by a French naval vessel in either late 1745 or early 1746 off the coast of Nova Scotia. The captured ship was a British merchant ship called the Lively, whose captain had decided to go privateering against the French. Stewart points out that the document was signed on January 6th, 1746 by Jean-Baptiste Louis Frederic de La Rochefoucauld, the Duc d’Anville who launched the famous and disastrous expedition to recapture Nova Scotia from the British. He further states that the French vessel which captured the Lively was “part of the Duc d’Anville’s fleet.” This statement is technically true, since any vessel in the French Navy could be considered part of the Duc’s fleet following d’Anville appointment to Lieutenant General of the French Navy in January 1745, as Stewart points out. However, it is important to remember that participants in the Duc D’Anville Expedition did not arrive in Nova Scotia until September 1746, and thus the ship which captured the Lively was not, at the time, a participant in the Duc D’Anville Expedition. Stewart suggests that the date of the signature on the document is an indication that the Duc d’Anville was in the Nova Scotia area at the time of the Lively’s capture, stating, “He wouldn’t have done that from France or anywhere else. He must have been there at that time.” If Stewart went on to explain the reasoning behind this supposition, that scene did not make it into the final cut of this episode.

The narrator then beautifully summarizes the development thus:

“At the National Archives in London, England, researcher Paul Stewart has just presented official documents that state the French admiral known as the Duc d’Anville, who reportedly led a mission to bury treasure in Nova Scotia back in September of 1746, visited the area near Oak Island nine months earlier.”

Capture Document of the Diamont

Next, Paul Stewart shows the treasure hunters capture documents signed by British Admiral George Anson, whom he explains was interested in “collecting intelligence about the Duc d’Anville fleet.” The narrator then reminds us that George Anson features in another Oak Island theory involving the mysterious Shugborough Hall with its ominous Shepherd’s Monument and cryptic Shugborough Inscription.

One of the capture documents which Stewart shows the treasure hunters details the seizure of a French vessel called the Diamont, captained by an officer called La Chevalier Hoequart. The battle in which the Diamont was taken is described in William Laird Clowes’ 1898 book The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present.

Before we launch into Clowes’ narrative, it may be worth our while to take a look at Captain Hoequart’s known movements prior to the capture of his ship, which seem to challenge a statement made by Stewart in this episode that the Diamont was part of the original Duc d’Anville Expedition fleet. According to an 1894 French-language history of Prince Edward Island called Une Second Acadie, written by Quebecois historian and Catholic clergyman Abbot Henri-Raymond Casgrain, Captain Hoequart’s Diamont was one of seven ships which assembled on the St. Lawrence River off Quebec City in the spring of 1746, about half a year prior to the Duc d’Anville Expedition. In June, the squadron relocated to the Gaspe Peninsula, where they received news of the arrival of two frigates called L’Aurore and Le Castor, French scouting ships dispatched to Nova Scotia’s Chebucto Bay several months in advance of the Duc d’Anville’s main fleet. The French navy men at Gaspe also learned that the British had captured Port La Joie, the French capital of what is now Prince Edward Island. With the help of Mi’kmaq warriors, they conducted a surprise attack on the British and killed dozens of soldiers in what proved to be the bloodiest massacre ever perpetrated on the island. Casgrain’s narrative seems to imply that Hoequart and his Diamont were actively engaged in the Canadian theatre of the War of Austrian Succession prior to the Duc d’Anville’s disastrous voyage across the Atlantic, and were therefore probably not part of the main d’Anville fleet.

One year later, in the spring of 1747, following the disastrous Duc d’Anville Expedition, a squadron of ships under the command of Admiral Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel Jonquiere, Marquis de la Jonquiere, departed from France with the intention of recapturing Cape Breton Island, or Ile Royale, from the British. “The projects of the French were known in England,” wrote William Clowes, “and a squadron, under Vice-Admiral George Anson and Rear-Admiral Peter Warren, was specially fitted out to checkmate them…”

The two fleets engaged each other on the afternoon of May 3rd, 1747, in the waters off Cape Finisterre, on the west coast of Spain. The French fleet was greatly outnumbered, and had among its number several French East India Company trading ships which had been impressed into service, whose captains had no appetite for battle. After a running fight lasting from 4 to 7 P.M. “in which several of the French captains behaved with great courage and others conducted themselves with equal cowardice,” all of the French ships still fit to sail fled across the Atlantic and escaped under the cover of darkness.

“The battle, considering its nature, was a costly one,” Clowes wrote. “The French lost about 700 killed and wounded, and the British, 520… The victors found specie to the value of 300,000 GBP on board the prizes. For this service Anson was created a peer, and Warren a Knights Baronet. All the men-of-war taken… were purchased into the Royal Navy. The name of the Serieux was changed to Intrepid, and that of the Diamont to Isis.”

In the show, Paul Stewart reveals the fate of the unfortunate captain of the Diamont, saying, “Hoequart was captured by Admiral Anson. Anson put him in prison and gave him a hard time in prison. Anson obviously wanted to try to find out something about what was on the ship… He wanted to find out what they’d been up to when they were along the coast of Mahone Bay… Anson ended up getting letters from all sorts of top people in France to try and get Hoequart out. One of the letters that was sent from France looks pretty certainly to be from the Rochfoucauld family, and Anson wouldn’t let him out for a long time.”

Alex Lagina then speculates that if the Oak Island treasure was indeed deposited by members of the Duc d’Anville Expedition, that Lord Anson became aware of that fact through the interrogation of Captain Hoequart, and that the British subsequently began to search for the buried French treasure on Oak Island, it would explain the plethora of both French and British artifacts which the crew has unearthed on the island over the years.

In a War Room meeting near the end of the episode, Marty, Alex, and Charles tell the team about their discoveries and experiences in England via video conference. Rick Lagina suggests a potential connection between the carving of what Cornwall believes to be a mermaid-like Melusine on the walls of Royston Cave to a drawing of a fish on Zena Halpern’s 1347 map of Oak Island.

Leave a Reply