Viking Voyages to Canada

Who discovered America?

This question will yield a number of different answers depending on whom you ask.

Canadian schoolkids fresh from Social Studies class may recall that Italian navigator John Cabot discovered the rocky shores of Labrador in 1496 on behalf of King Henry VII of England.

American schoolkids might be just as quick to point out that another Italian navigator, Christopher Columbus, discovered the sandy beaches of Cuba four years earlier on behalf of Queen Isabella I of Castile.

Fans of The Curse of Oak Island may pipe up that Portuguese explorer Joao Vaz Corte-Real may have discovered Newfoundland in 1473 on behalf of Alfonso V, King of Portugal.

And people of Native American pedigree may remind you that their ancestors emigrated from Siberia up to 14,000 years ago.

If you ask a member of Canada’s Scandinavian communities, however, such as the residents of Gimli, Manitoba, or New Denmark, New Brunswick, you may hear a tale that was passed down centuries ago by their medieval ancestors- the tale of Viking voyages to Canada which took place more than a thousand years ago.

Who Were the Vikings?

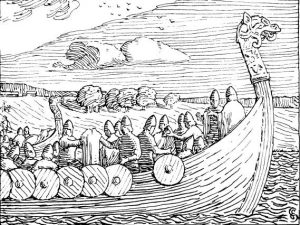

The Norse Vikings were a hardy sea-faring folk from Scandinavia who lived in small kingdoms during the Early Middle Ages. For most of the year, they lived as farmers and fishermen, scraping out as good a living as their harsh northern environment would allow. When summer came, wealthy farmers would leave their lands in the hands of their wives, recruit a company of loyal friends and kinsmen, and set sail in search of fortune and adventure.

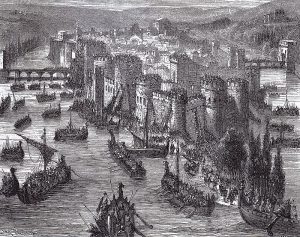

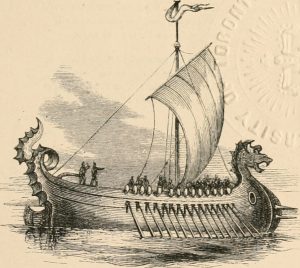

From the late 700s until the mid-1000s, during what is known as the ‘Viking Age’, Norse raiders sailed up and down the coastlines and rivers of Europe, pillaging and plundering as they went. With lightning speed, they attacked villages, churches, and monasteries, retreating to their longships with any booty they could lay their hands on before their victims had a chance to organize any sort of resistance. For centuries, the sight of a Viking longship with a carved dragon’s head on its prow and a row of shields lashed to its side struck terror into the hearts of peasants and clergymen from Moscow to Madrid.

From the late 700s until the mid-1000s, during what is known as the ‘Viking Age’, Norse raiders sailed up and down the coastlines and rivers of Europe, pillaging and plundering as they went. With lightning speed, they attacked villages, churches, and monasteries, retreating to their longships with any booty they could lay their hands on before their victims had a chance to organize any sort of resistance. For centuries, the sight of a Viking longship with a carved dragon’s head on its prow and a row of shields lashed to its side struck terror into the hearts of peasants and clergymen from Moscow to Madrid.

Over time, the Vikings transitioned from reaving and pillaging to consolidating and colonizing. Many became settlers at the places they had once ravaged. For example, the enormous Norse raider named Rollo, whom some may recognize as a character from the History Channel series Vikings, became the first Duke of Normandy in the year 911; his great-great-great grandson, William the Conqueror, would go on to wrest England from control of the ruling Anglo-Saxon king at the Battle of Hastings (1066). Around the same time, Norse warlord Harald Fairhair united a cluster of petty Viking kingdoms, which had warred with each other for centuries, into a single Kingdom of Norway.

Many Viking chieftains who were unable to retain their power in this age of unification chose to sail west in search of new lands. In around 860 A.D., some of these political refugees discovered and settled Iceland. Less than a century later, their descendants would establish the Icelandic Commonwealth, which was governed in part by the Althing, the oldest parliament in the world.

Many Viking chieftains who were unable to retain their power in this age of unification chose to sail west in search of new lands. In around 860 A.D., some of these political refugees discovered and settled Iceland. Less than a century later, their descendants would establish the Icelandic Commonwealth, which was governed in part by the Althing, the oldest parliament in the world.

Erik the Red and the Settlement of Greenland

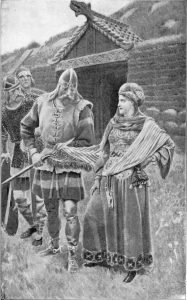

In 960 A.D., a Norse Viking named Thorvald Asvaldsson fled from Norway to northwestern Iceland with his family, having been banished for committing manslaughter. His son, a red-bearded farmer called Erik the Red, was similarly banished from Iceland twenty two years later for a comparable crime. Accompanied by a handful of loyal friends and relatives, Erik the Red left his longhouse and headed out to sea, bound for a mysterious land to the west which had been spotted by Icelandic sailors blown off course.

Erik the Red and his crew spent three years exploring this new land, and discovered that it had areas which were suitable for farming. In 985, the red-bearded explorer returned to Iceland and regaled his fellow Vikings with tales of what he attractively dubbed “Groenland”, or “Greenland”. Having convinced a number of Norsemen to help him settle this new territory, Erik the Red returned to Greenland that year and established a colony there, which was named Eriksfjord.

Erik the Red and his wife eventually had four children: a lucky son named Leif; a brave son named Thorvald; a selfless son named Thorstein; and a cunning daughter named Freydis. Their subsequent discovery of a mysterious land to the west became the stuff of legend. For generations, Scandinavians spoke of their New World adventures around smoky longhouse fires. Medieval storytellers eventually put these tales to parchment, writing what are known as the Icelandic Sagas.

The Viking Discovery of Canada

There are two sagas which detail the Viking discovery of the New World: The Saga of Erik the Red (written before 1265), and the older Greenland Saga, both of which were written several centuries after the events they purport to chronicle. The events outlined in the sagas are also referenced briefly in 11th Century German chronicler Adam of Bremen’s book Descriptio Insularum Aquilonis (1075), a history of the northern world, as well as in 12th Century Icelandic historian Ari Thorgilsson’s book Islendingabok, or “Book of the Icelanders”.

The following are summaries of chapters of the Icelandic sagas which pertain to the Norse discovery of the Americas.

The Greenlander Saga

Bjarni Herjolfsson’s Discovery

Around the time of Erik the Red’s settlement of Greenland, a Norseman named Bjarni Herjolfsson had a tradition of alternately wintering in Norway, the Norse homeland, and in Iceland, where his father, Herjolf, lived. One autumn, Bjarni sailed from Norway to Iceland to discover that his father had emigrated to Erik the Red’s Greenlandic colony. Determined to winter with his father as was his custom, he and his crew sailed west.

Around the time of Erik the Red’s settlement of Greenland, a Norseman named Bjarni Herjolfsson had a tradition of alternately wintering in Norway, the Norse homeland, and in Iceland, where his father, Herjolf, lived. One autumn, Bjarni sailed from Norway to Iceland to discover that his father had emigrated to Erik the Red’s Greenlandic colony. Determined to winter with his father as was his custom, he and his crew sailed west.

Bjarni and his men soon encountered storms which blew them off course. When the fog cleared, the Norsemen found themselves within sight of a strange wooded land. Ignoring the entreaties of his curious crewmen, Bjarni refrained from embarking and sailed north. He came within sight of two more strange lands, neither of which he explored, before finally finding his way to Greenland.

The tale of Bjarni’s discoveries became the talk of the colony, and soon Leif Erikson, Erik the Red’s eldest son, decided to lead an expedition west in search of them. Although the elderly Erik the Red initially agreed, with some reluctance, to accompany his son, an omen convinced him to remain behind.

The Voyage of Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson and his crew sailed west and soon came to a barren, icy land covered with flat stones. He called this place Helluland, or “Flat-stone-land”. Most historians believe that Helluland was likely the eastern shores of Baffin Island, the largest island in Canada.

Finding Helluland to be of little interest, Leif and his crew continued south. Eventually, they came to a rugged land of evergreen woods and white shores. The Vikings called this place Markland, or “Forestland”. Most historians believe that Markland is likely northern Labrador.

Leif and his crew continued south, sailing for two days with a wind that blew from the northeast, before coming to a temperate land carpeted with thick dewy grass. The Vikings felt that this would be a good place to spend the winter and set about building houses. That accomplished, Leif sent half his men out to explore this new land.

When one of Leif’s friends, a German named Tyrker, failed to return, Leif led a search party to find him. The Norsemen eventually found Tyrker unharmed but babbling excitedly in German. When they finally managed to calm him down, Tyrker informed them, in Norse, that he had discovered grapevines not unlike those from his German homeland. Leif ordered his men to harvest the grapes, which were so plentiful that the Scandinavians were forced to store them in a small boat and tow it behind their main ship. Leif Erikson dubbed this new land Vinland, or “Wineland”, on account of this pleasant discovery.

Today, there is some debate among historians over the location of Vinland. Many believe Vinland to be Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula, since archaeological evidence recovered there corresponds quite well with the sagas’ descriptions of the colony that the Norse allegedly founded. Others, observing that wild grapes do not grow north of New Brunswick, maintain that Vinland must be located further south. Champions of the former theory counter this argument by suggesting that either Leif and his Vikings mistook gooseberries, which Newfoundland has in abundance, with grapes, or that Leif Erikkson invented the grape story out of whole cloth, giving the land he discovered an attractive name, like his father did upon discovering Greenland, in an attempt to attract colonists.

The Voyage of Thorvald Erikson

After spending a pleasant winter in Vinland, Leif Erikson and his crew returned to Greenland, their ships filled with grapes and timber. The tales they told of their adventures piqued the curiosity of their fellows, and soon Leif’s brother, Thorvald, decided to see this New World for himself.

Setting sail with a crew of thirty men, Thorvald Erikson followed Leif’s route west to Helluland, south down the coast of Markland, to Vinland. The Vikings found the derelict remains of Leif’s camp and, Thorvald having leased these properties from his brother back in Greenland, spent the winter there.

Setting sail with a crew of thirty men, Thorvald Erikson followed Leif’s route west to Helluland, south down the coast of Markland, to Vinland. The Vikings found the derelict remains of Leif’s camp and, Thorvald having leased these properties from his brother back in Greenland, spent the winter there.

In the spring, Thorvald and his men sailed west on an exploratory expedition. They found little sign of human presence and decided to return to Leif’s camp to spend another winter.

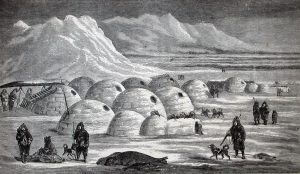

The following summer, Thorvald and his crew made an exploratory expedition to the northeast. One day, after returning to their ship from an inland trek, the Vikings found three brown lumps on the sand not far from their vessel. They cautiously approached the objects and found that they were upside-down skin boats, beneath each of which slept three strange-looking men. Viking lore being littered with tales of goblins, dwarves, elves, and hostile spirits, Thorvald and his crew were anxious to learn whether the strange inhabitants of this foreign land were flesh-and-blood beings or supernatural entities. They began to murder the natives, and managed to kill eight of them; the last escaped in his boat.

The following summer, Thorvald and his crew made an exploratory expedition to the northeast. One day, after returning to their ship from an inland trek, the Vikings found three brown lumps on the sand not far from their vessel. They cautiously approached the objects and found that they were upside-down skin boats, beneath each of which slept three strange-looking men. Viking lore being littered with tales of goblins, dwarves, elves, and hostile spirits, Thorvald and his crew were anxious to learn whether the strange inhabitants of this foreign land were flesh-and-blood beings or supernatural entities. They began to murder the natives, and managed to kill eight of them; the last escaped in his boat.

Exhausted from the ordeal, Thorvald and his men lay down to sleep. They awakened just in time to see a large party of natives approaching them, brandishing bows and arrows. The Vikings formed a shield wall to defend themselves and allowed the natives, whom they called “Skraelings”, to pelt them with projectiles. When the natives saw that their barrage had little effect on the Northmen, they retreated.

When Thorvald determined that none of his men had been wounded in the skirmish, he revealed that he had received a bone-shod arrow in his armpit, it having glanced off the side of the ship to circumvent his shield. Thorvald knew that he was mortally wounded and asked his men to bury him on a particular piece of land jutting into the sea, on which he had hoped to build a house. The Norsemen did as their captain requested and returned home to Greenland.

The Ghost of Thorstein Erikson

When Thorstein Erikson (Erik the Red’s third son) heard of Thorvald’s death, he determined to sail to Vinland to retrieve his brother’s body. With 25 men and his wife, Gudrid, Thorstein appropriated his brother’s ship and set sail for the New World.

When Thorstein Erikson (Erik the Red’s third son) heard of Thorvald’s death, he determined to sail to Vinland to retrieve his brother’s body. With 25 men and his wife, Gudrid, Thorstein appropriated his brother’s ship and set sail for the New World.

After sailing all summer, Thorstein and his crew were unable to find Vinland. Eventually, they made landfall on a settlement on the western shores of Greenland, not far from where they had first embarked.

Winter was nearly upon them, and so Thorstein Erikson secured lodging for all his men. Without any money left for himself, he and Gudrid were forced to sleep on their ship. Fortunately, a local farmer named Thorstein the Black, who lived a lonely life and desired company, approached Thorstein Erikson and invited him and Gudrid to winter with him and his wife, Grimhild. The couple gratefully accepted his hospitality.

That winter, a sickness swept through the settlement and killed many of Thorstein Erikson’s men. Thorstein Erikson himself eventually fell ill, along with his host’s heavyset wife, Grimhild. Although both Thorstein and Grimhild had been healthy and robust, they, too, eventually succumbed to the malady.

Gudrid was deeply affected by her husband’s passing and kept a gloomy vigil over her Thorstein’s corpse, which her bereaved host had laid out on a bench inside his house. Thorstein the Black, taking pity on the grieving widow, picked her up in his arms and sat her down on his lap on a bench opposite Thorstein Erikson’s body. The Norseman did his best to comfort his guest and promised to accompany her to her Eriksfjord, where Thorstein was to be buried.

No sooner had Gudrid thanked Thorstein the Black for his consolation than her late husband sat up on the bench. “Where is Gudrid?” the corpse asked. Astonished and terrified, neither the widow nor widower dared answer. The dead man repeated the question twice.

“Should I answer his questions or not?” Gudrid whispered to her host. Thorstein the Black shook his head.

The corpse remained seated and so, after transferring Gudrid to another chair further from the dead man, Thorstein the Black asked, “What wilt thou, Namesake?”

“I wish much to tell Gudrid her fortune,” the corpse replied, “in order that she may be the better reconciled to my death, for I have now come to a good resting place.” The dead man proceeded to inform Gudrid that she would marry an Icelander, and that she and her new husband would have many “powerful, distinguished, and excellent, sweet and well-favoured” descendants. She would move to Norway, then to Iceland, and would outlive her husband. She would travel the world, visit Rome, and live out the rest of her days as a nun in an Icelandic convent. When the prophecy was finished, Thorstein Erikson’s corpse fell back onto the bench and lay still.

True to his word, Thorstein the Black took Gudrid to Eriksfjord. There, Thorstein Erikson’s body was interred in the graveyard of the local church.

Thorfinn Karlsefni’s Voyage

After Thorstein Erikson’s ill-fated voyage, Greenlandic Vikings began discussing a potential future voyage to Vinland. Around that time, a Norwegian ship arrived in Greenland’s western shore, captained by Thorfinn Karlsefni, a wealthy Icelander. Thorfinn was hosted by Leif Erikson, who introduced him to his sister-in-law, Gudrid. Thorfinn and Gudrid fell in love, and that winter they married, just as Thorstein Erikson had predicted.

After Thorstein Erikson’s ill-fated voyage, Greenlandic Vikings began discussing a potential future voyage to Vinland. Around that time, a Norwegian ship arrived in Greenland’s western shore, captained by Thorfinn Karlsefni, a wealthy Icelander. Thorfinn was hosted by Leif Erikson, who introduced him to his sister-in-law, Gudrid. Thorfinn and Gudrid fell in love, and that winter they married, just as Thorstein Erikson had predicted.

When spring came, Thorfinn Karlsefni decided to lead an expedition to Vinland. Accompanied by sixty men, five women, and his wife, Gudrid, he sailed past Helluland and Markland to the Vinlandic houses that Leif Erikson had built. Having leased the houses from Leif, Thorfinn and his companions prepared for winter, butchering and processing the carcass of a beached whale that they found nearby.

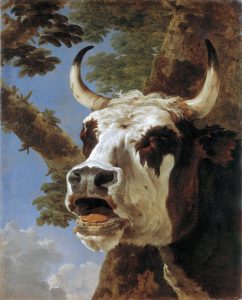

That winter, Thorfinn Karlsefni and his Vikings wanted for nothing, finding plenty of timber, grapes, fish, and game. They also enjoyed fresh milk from a handful of cows that they had brought with them, which were protected against wild animals by a bull they had transported in the hold of their ship.

That summer, a band of Skraelings approached the pasture where the Norsemen kept their cattle. The bull began to bellow at the newcomers, and the natives, having never seen such an animal before, retreated in fear. The Skraelings then proceeded to Thorfinn’s farm. Forewarned of their coming, the Vikings barricade themselves inside the farmhouse.

That summer, a band of Skraelings approached the pasture where the Norsemen kept their cattle. The bull began to bellow at the newcomers, and the natives, having never seen such an animal before, retreated in fear. The Skraelings then proceeded to Thorfinn’s farm. Forewarned of their coming, the Vikings barricade themselves inside the farmhouse.

It soon became evident that the natives had come to trade, not to make war. The Vikings eventually emerged from the farmhouse and began to inspect the fine animal pelts the Skraelings had brought with them for barter. The natives indicated that they would like to exchange their pelts for the Vikings’ swords and axes. Loathe to equip the Skraeling with steel weapons, however, Thorfinn instead had the women bring out milk and cheese. After sampling these exotic foods and finding them to their liking, the Skraelings happily exchanged their furs for dairy products and left contented.

Once the Skraelings were gone, Thorfinn had the Vikings build a palisade around his longhouse. While the work commenced, Gudrid gave birth to a boy, whom she and Thorfinn named Snorri. And thus Snorri Thorfinnson became the first white child to be born in the Americas.

That winter, the Vikings were visited again by a much larger force of Skraelings. Again, the natives appeared intent on trading, and threw bales of furs over the palisade. During the exchange, one of the natives reached for a Viking weapon. Startled, one of Thorfinn’s men slew him. A panic ensued, and the natives retreated.

Thorfinn knew that the Skraelings would return to revenge their fallen comrade. Recalling the effect that the bull had made on them, he decided to unleash the animal in order to scare them off. When the natives arrived as anticipated, Thorfinn irritated the bull and allowed it to charge at unsuspecting natives. His plan worked, and the Skraelings retreated. He and his Norsemen killed many of the natives in the ensuing route.

The natives never returned to the Viking village that winter, and when spring came, Thorfinn and his company sailed back to Greenland with lumber, grapes, whale oil, and furs.

Freydis’ Expedition

When the Norsemen of Greenland saw the rich haul that Thorfinn Karlsefni had brought from the New World, many began to consider making another expedition to Vinland. Two such men were brothers Helgi and Finnbogi- Icelanders who had arrived in Greenland that summer.

Another Northerner with her sights set on Vinland was Freydis, the only daughter of Erik the Red. That winter, Freydis payed a visited to Helgi and Finnbogi and suggested that they sail to Vinland together and split any profits they managed to acquire there. The brothers agreed to her proposal.

It was arranged that Freydis and the brothers would each bring thirty fighting men with them to the New World, in addition to their women, so that neither party would have an advantage over the other. Freydis duplicitously broke this agreement by hiding five additional men on her own ship. Helgi and Finnbogi were unaware of her deceit until they reached Vinland.

It was arranged that Freydis and the brothers would each bring thirty fighting men with them to the New World, in addition to their women, so that neither party would have an advantage over the other. Freydis duplicitously broke this agreement by hiding five additional men on her own ship. Helgi and Finnbogi were unaware of her deceit until they reached Vinland.

After a brief dispute, it was agreed that Freydis and her party would use the longhouses that Leif Erikson built, and that the brothers and their men would build their own dwelling.

No sooner had Helgi and Finnbogi constructed their longhouse than winter came. In order to pass the time, they invited Freydis’ crew to play sports with them. Disputes between the players quickly sowed discord which resulted in both camps spending the rest of the winter alone, in their respective longhouses.

One morning, Freydis rose from her furs, slipped on her sark and smokkr (shirt and skirt), and slipped out the door without bothering to put on shoes or stockings. Wearing her husband’s cloak, she walked over to the brothers’ longhouse, found the door ajar, and stood in the threshold. Finnbogi, the only man awake at that time, noticed Freydis in the doorway and asked what she was doing there.

“I wish that thou wouldst get up and go out with me,” she replied, “for I will speak with thee.” Finnbogi did as Freydis requested and went outside to sit with her on a tree that the brothers had felled.

“How art thou satisfied here?” Freydis asked.

Finnbogi replied that he enjoyed Vinland and its abundance resources, but admitted that he did not like the discord that had sprung up between their two camps, and thought that there was no reason for it. Freydis agreed before stating that the purpose of her visit was to trade ships with the brothers, as theirs was bigger than hers, and she wished to return to Greenland. Finnbogi agreed to her proposal. With that, the two concluded their meeting.

Freydis returned to her longhouse and slipped into bed. Her frozen feet awoke her husband, Thorvard, who asked why she was so cold and wet.

With a bitter sob, Freydis falsely claimed that she had visited the brothers in order to ask them about exchanging ships, only to be beaten and used shamefully. “But thou, miserable man,” she snarled with reproach, “wilt surely neither avenge my disgrace nor thine own.” She then threatened to leave Thorvard once they arrived in Greenland if he failed to avenge her.

Thorvard, none the wiser, threw off his furs in a rage. He roused his kinsmen and led them to Helgi and Finnbogi’s longhouse, where the brothers and their men were asleep. Thorvard’s Norsemen bound each of their hapless countrymen and led them out of the house, where Freydis had each of them executed.

Thorvard, none the wiser, threw off his furs in a rage. He roused his kinsmen and led them to Helgi and Finnbogi’s longhouse, where the brothers and their men were asleep. Thorvard’s Norsemen bound each of their hapless countrymen and led them out of the house, where Freydis had each of them executed.

At the end of the massacre, only five women remained from the brothers’ camp, whom none of the men would consent to kill. “Give me an axe!” cried Freydis, seizing a weapon from one of her husband’s men. The furious Norsewoman proceeded to hack each of her female compatriots to death.

When the slaughter was complete, Freydis rounded on her husband’s crew and threatened to kill any of them who spoke of the bloodbath upon their return to Greenland. If asked what became of the brothers and their crew, they were to answer that they remained behind in Vinland.

When spring came, the Scandinavians loaded the brothers’ ship with everything they had acquired that year and put to sea. The homeward voyage was an uneventful one, and the Vikings arrived at Eriksfjord in early summer.

In spite of Freydis’ threat, word of the Vinland massacre began to circulate throughout the colony. Incensed, Leif Erikson captured three of Freydis’ men and tortured them until they confessed the whole bloody business. Although Leif suggested that his sister deserved the same treatment, he decided to leave her be, believing that the curse that would hang over her posterity, which her wicked deeds had surely incurred, would be punishment enough.

The Saga of Erik the Red

The Saga of Erik the Red paints a very different picture of the Viking discovery of the Americas than that outlined in the Greenland Saga, although there is also much overlap between the two. Instead of Bjarni Herjolfsson, the Saga of Eric the Red contends that Leif Erikson was the first Norseman to see the shores of the New World.

When he was a young man, the saga goes, Leif left Greenland, the place of his birth, and travelled to Norway, his father’s homeland. There, he found his way into the service of Olaf Tryggvason, King of Norway.

Olaf converted Leif to Christianity and tasked him with bringing the Christian religion to Greenland. Leif obeyed and sailed west. During the voyage, “he was tossed about a long time out at sea, and lighted upon lands of which before he had no expectation. There were fields of wild wheat, and the vine-tree in full growth. There were also maple trees.”

There, Leif rescued a party of shipwrecked Norseman and brought them back with him to Greenland and gave them food and lodging throughout the winter. “Thus,” the saga goes, “did he show his great munificence and his graciousness when he brought Christianity to the land, and saved the shipwrecked crew. He was called Leif the Lucky.”

Back in Greenland, Leif Erikson began to evangelize his fellow Norsemen. Many of the colonists, including Leif’s mother, converted to Christianity. Leif’s father, Erik the Red, was one of the few who refused to convert, staunchly adhering to the Norse paganism of his ancestors.

Erik the Red’s Expeditions

Although Erik the Red had little use for the new religion that his son brought to Greenland, he did take a keen interest in the bountiful land that Leif had discovered. He set out with twenty men to find it, but encountered a storm which blew his ship east nearly to Ireland.

Following that unsuccessful attempt, a much larger expedition was organized, consisting of many ships and 160 men. According to the saga:

Following that unsuccessful attempt, a much larger expedition was organized, consisting of many ships and 160 men. According to the saga:

“They were out at sea two half-days. Then they came to land, and rowed along it in boats, and explored it, and found there flat stones, many and so great that two men might well lie on them stretched on their backs with heel to heel. Polar foxes were there in abundance. This land they called ‘Helluland’.

“Then they sailed with northerly winds two half-days, and there was then land before them, and on it a great forest and many wild beasts. An island lay to the southeast, and they found bears and called the island ‘Bjarney’ (Bear Island). The mainland, where the forest was, they called ‘Markland’ (Forest Land).”

Finally, the Viking explorers came to a pleasant cape where the coast was veined with creeks. As sailing was perilous along that stretch of coast, they sent two scouts to head south on foot to see what could be found. The men returned saying that there were two good lands further south. One was choked with wild grapes, while the other was rich with wild wheat.

The Vikings then sailed south down the coast and up a strait, at the mouth of which lay an island encircled by strong currents. According to the saga, “There were so many birds on [the island] that it was scarcely possible to put one’s feet down for the eggs”. The Norsemen continued up the firth, lowered their anchor, and prepared their camp.

After spending a hungry winter in the camp, near which there were mountains and large pastures, the expedition split up. One party attempted to return to Greenland but was blown off course; the Norsemen ended up in Ireland. The other group, led by Thorfinn Karlsefni, travelled south. After some time, they came to river which emptied into a lake, which, in turn, drained into the sea. The land near the river’s mouth, which was dotted with large islands, was abundant in wild wheat, while its heights were choked with wild grapes. The river itself teemed with fish, and the woods were abundant with all variety of wild animals. Thorfinn and his company camped in the area for about half a month, spending their time hunting and fishing and playing games.

Encounters with the Skraelings

“Early one morning,” the saga goes, “as they looked around, they beheld nine canoes made out of hides, and snout-like staves were being brandished from the boats, which made a noise like flails, and twisted round in the direction of the sun’s motion.”

“Early one morning,” the saga goes, “as they looked around, they beheld nine canoes made out of hides, and snout-like staves were being brandished from the boats, which made a noise like flails, and twisted round in the direction of the sun’s motion.”

Thorfinn and his companion, Snorri (his son’s namesake), speculated as to the meaning of this strange activity. “It may be that it is a token of peace,” Snorri suggested, before proposing that they approach the canoeists with a white shield- a Viking token of peace.

The Norsemen followed Snorri’s suggestion and cautiously approached the shore with their white shield held high. The canoeists, in turn, began to paddle towards the shore. “They were short men,” the saga goes, “ill-looking, with their hair in disorderly fashion on their heads. They were large-eyed and had broad cheeks. They stayed there a while in astonishment. Afterward, they rowed away to the south, off the headland”.

The Northmen spent the winter near the mouth of the river, during which they saw neither snow nor any more of the mysterious natives, whom they called Skraelings.

“Now when spring began,” the saga continues, “they beheld early one morning that a fleet of hide canoes was rowing from the south off the headland. There were so many that it was as if the sea were strewn with pieces of charcoal, and there was also the brandishing of staves as before from each boat. Then they held shields up, and a market was formed between them.”

“Now when spring began,” the saga continues, “they beheld early one morning that a fleet of hide canoes was rowing from the south off the headland. There were so many that it was as if the sea were strewn with pieces of charcoal, and there was also the brandishing of staves as before from each boat. Then they held shields up, and a market was formed between them.”

The natives proceeded to trade grey furs for red cloth. They also wished to purchase swords and lances, but Thorfinn and Snorri forbade their countrymen from selling the natives steel weapons. While the trading ensued, a bull that belonged to Thorfinn Karlsefni rushed out of the woods and bellowed loudly. The Skraelings became frightened and rowed south in their canoes.

Three weeks later, a large party of canoe-going Skraelings approached the Viking camp from the stream, brandishing spears and howling war cries. The Norsemen took red shields, a signal that they were ready for battle, and rushed to meet them. The Skraelings showered the Vikings with arrows and slung rocks. They also brought with them strange weapons which the saga describes thus:

“Karlsefni and Snorri saw the Skraelingjar were bringing up poles with a very large ball attached to each, comparable in size to a sheep’s stomach, dark in color. These flew over Karlsefni’s company towards the land, and when they came down they struck the ground with a hideous noise. This produced great terror in Karlsefni and his company, so that their only impulse was to retreat up the country along the river, because it seemed as if crowds of Skraelingjar were driving at them from all sides. And they did not stop until they came to some crags. There, they offered them stern resistance.

“Karlsefni and Snorri saw the Skraelingjar were bringing up poles with a very large ball attached to each, comparable in size to a sheep’s stomach, dark in color. These flew over Karlsefni’s company towards the land, and when they came down they struck the ground with a hideous noise. This produced great terror in Karlsefni and his company, so that their only impulse was to retreat up the country along the river, because it seemed as if crowds of Skraelingjar were driving at them from all sides. And they did not stop until they came to some crags. There, they offered them stern resistance.

“Freydis came out and saw how they were retreating. She called out, ‘Why do you run away from such worthless creatures, stout men that you are, when, as seems to me likely, you might slaughter them like so many cattle? Let me have a weapon. I think I could fight better than any of you.

“They gave no heed to what she said. Freydis tried to accompany them, but soon lagged behind because she was not well. She went after them into the wood and the Sraelingjar directed their pursuit after her. She came upon a dead man, Thorbrand, Snorri’s son, with a flat stone fixed in his head. His sword lay beside him, so she took it up and prepared to defend herself.

“The Skraelingjar came upon her. She let down her sark and struck her beast with the naked sword. At this they were frightened, rushed off to their boats, and fled. Karlsefni and the rest came up to her and praised her zeal. Two of Karlsefni’s men fell, and four of the Skraelingjar…”

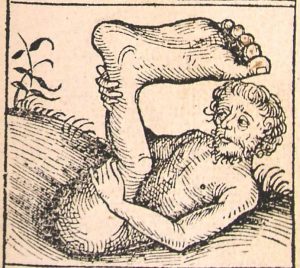

Land of the One-Footers

Although the land was bountiful, the Vikings decided that the Skraeling were too numerous to allow for any permanent settlement and headed north. A hundred of them, Freydis and Bjarni included, decided to remain at the strait at which they had previously camped, while the remainder explored more of the region.

The saga then tells us that, while exploring a river north of Vinland, Thorfinn Karlsefni and his crew encountered a “One-Footer” (also known as a “monopod” or a “sciapod”), a mythological one-legged dwarf which hopped from place to place. The monster shot Thorvald Erikson in the lower abdomen with an arrow. The Viking pulled the projectile out of his gut and remarked that Vinland must be bountiful indeed, as he had grown such a belly that winter that the arrow had failed to harm him. The One-Footer then hopped away to the north.

After briefly visiting the land of the One-Footers, Thorfinn and his crew returned to the camp at the strait. That fall, Thorfinn and Gudrid had their first son, Snorri.

After spending three more years in the area, the Vikings sailed for home. On the way, they stopped in Markland, where they found a family of Skraelings. “One was a bearded man,” the saga goes, “two were women, two children. Karlsefni’s people caught the children, but the others escaped and sunk down into the earth. They took the children with them, and taught them their speech, and they were baptized.”

The saga continues:

“The children called their mother Vaetilldi and their father Uvaegi. They said that kings ruled over the land of the Skraelingjar, one of whom was called Avalldamon, and the other Valldidida. They said that there were no houses, and the people lived in caves or holes. They said, moreover, that there was a land on the other side over against their land, and the people there were dressed in white garments, uttered loud cries, carried long poles, and wore fringes. This was supposed to be [White Man’s Land]. Then came they to Greenland, and remained with Erik the Red during the winter.”

“The children called their mother Vaetilldi and their father Uvaegi. They said that kings ruled over the land of the Skraelingjar, one of whom was called Avalldamon, and the other Valldidida. They said that there were no houses, and the people lived in caves or holes. They said, moreover, that there was a land on the other side over against their land, and the people there were dressed in white garments, uttered loud cries, carried long poles, and wore fringes. This was supposed to be [White Man’s Land]. Then came they to Greenland, and remained with Erik the Red during the winter.”

The Discoveries at L’Anse Aux Meadows

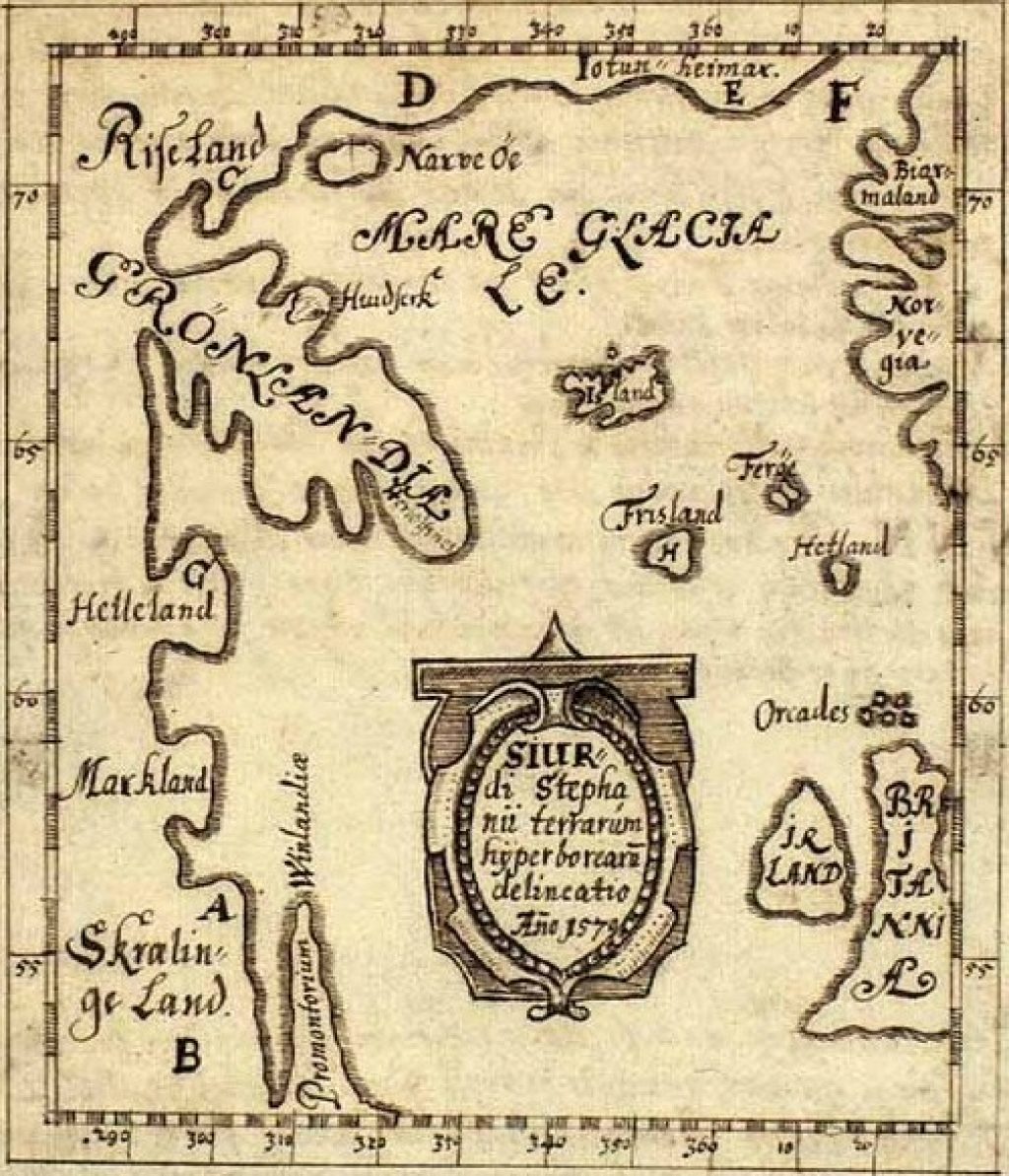

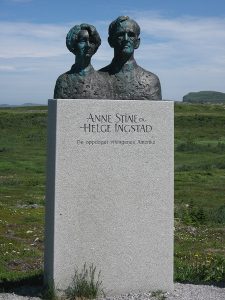

In 1960, a 60-year-old Norwegian trapper named Helge Ingstad, along with his wife Anne Stine, set out to prove once and for all that the Viking sagas were true, and that the Norse really had explored and briefly colonized the Americas in the Middle Ages. Aided by a copy of the Skalholt map, a 16th Century Icelandic document which alleged to show the relative locations of Helluland, Markland, and Vinland, they began traveling around the rugged coast of Newfoundland, examining different areas and interviewing the locals.

“And people,” said Helge in an interview in later life, “old fishermen, thought I was a little crazy asking about the settlement that was a thousand years old. But I kept on, and after many disappointments, late in the fall I came to the very northern part of Newfoundland, the very tip.”

There, near the town of L’Anse aux Meadows, Helge and Anne met a grizzled old fisherman named George Decker.

“I asked him the old question,” said Helge. “‘Have you seen any old… ruins here?’ And he was a very intelligent man. And he said, ‘Yes, I have. Follow me.’”

Decker led the couple to an assortment of grassy mounds, which locals had long assumed were the remains of some old Beothuk or Mi’kmaq camp. Helge and Anne Ingstad proceeded to excavate the mounds. What they found changed North American history forever.

Helge and Anne unearthed a number of interesting artifacts beneath the mounds at L’Anse aux Meadows, including a soapstone spindle whorl, iron nails, and charcoal which they carbon dated to around 1000 A.D. The most interesting find, however, was a Viking brooch which proved almost without a doubt that the area was once a Norse settlement.

Today, archaeologists believe that the ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows once consisted of eight buildings, three of them longhouses capable of housing around eighty people. Near the residential halls was a smithy where nails were made.

Some believe that the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows is none other than Leif Erikson’s Vinlandic colony. Others, noting that Newfoundland is devoid of wild grapes, believe Vinland to be further south, and suggest that the settlement at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula served as a stopping point, perhaps being the burial place of Thorvald Erikson or one of the camps referred to in the sagas.

Although we may never know the true location of Vinland, we do know without a doubt that long before John Cabot, Christopher Columbus, or even Joao Vaz Corte-Real stepped foot on American shores, Canada was a colony of the Vikings.

Sources

- Greenlander Saga (13th Century)

- Saga of Erik the Red (13th Century)

- The Vikings in North America: The History and Legacy of the Norse Settlements in Greenland and Vinland (2015), Charles River Editors

- Ancient Mysteries: Vikings in North America (1995), A&E

Gerry Burnie

Great story, Hammerson.

I’ve alwaysi.e. been fascinated by the Vikings and that era in general. My new novel has an underlying Norse theme involving Knut ‘The Great’ who was king of Denmark, Noway, and England in the 12th century.

Also, the Norse mythology, i.e. Ørlög and Scagi. Fascinating stuff!

Hammerson Peters

Thanks for the comment, Gerry. That sounds really interesting! Please feel free to leave a link to your book in the Comments section.